A Carol for Christmas: The King’s Singers Foundation Inaugurates First Composition Competition

By Graham Lack, composer & ICB Consultant Editor

A sense of expectation goes hand in hand with any new competition, and ‘A Carol for Christmas’, held for the first time in 2012 under the auspices of King’s College, Cambridge and The King’s Singers Foundation, certainly raised awareness of a rich tradition in the British Isles but also exemplified the parlous state of the genre. Supported too by Classic FM and Novello & Company (this imprint part of Music Sales Group), and sponsored by Woodfines Solicitors Cambridge, the competition was advertised as “a nationwide search for new carols”, with composers of all ages from across the UK “being invited to showcase their talent” in a “festive composition competition”. Prize-winners were guaranteed a performance in the stunning setting of King’s College Chapel, a recording for Classic FM, a cash prize of £250 and the opportunity to be published by Novello.

The competition was split into four categories, one of which gave composers the opportunity to write for the King’s Singers themselves. The first category was for an un-auditioned community choir, calling for a work written in unison or as a 2-part (SA) setting. It was open to submissions from composers of all ages. And carols could be submitted with or without keyboard accompaniment. The second category was for a composition for mixed choir (SATB), but composers had to be under 18. Again, works could be submitted with or without keyboard accompaniment. In the third category, also for SATB choir, composers could be aged 19 or over, and were able to submit either a cappella pieces or with keyboard accompaniment. Finally, in the fourth category, an a cappella composition for The King’s Singers (CtCtTBarBarB) could be submitted, open to submissions from composers of all ages.

A total of 322 carols were entered for this inaugural competition; composers’ ages ranged from 9 to 83. The jury of ‘A Carol for Christmas’ comprised Stephen Cleobury (Director of Music, Choir of King’s College, Cambridge), John Rutter (composer and record producer), and David Hurley – first countertenor with The King’s Singers.

During an afternoon event held at King’s College Chapel on 18th December 2012, the works by the winning composers of the first three categories were performed in a workshop environment, the compositions sung by youth choirs from throughout Britain, including King’s Junior Voices, CBSO Young Voices, the London-based Inner Voices, and Quay Voices from the North East of England. At the evening concert the same day, also in King’s College Chapel, the premiere of the winning piece in the final category was given by The King’s Singers. Both events were recorded for broadcast on Classic FM, and were presented by Tim Lihoreau, on 22nd December.

The Category 1 winner was Ruth Sellar, a music graduate from King’s College, London, with her carol Patapan, for un-auditioned community choir. Ruth is currently working at Bilton Grange Preparatory School, Rugby, where her role includes teaching piano and music theory, accompanying choirs and instrumentalists and playing at chapel services. Cast in a lilting 5/4 time, and with a rollicking piano accompaniment, the work seemed easy to master, the young singers rising well to the task. But as the melody bifurcated into discrete soprano and alto parts, the canonic writing seemed somehow less effective than simple unison, tailing off into hesitant intervals neither truly harmonic nor melodic. As for the melody itself, well, a catchy tune is a fine thing and not as easy to write as one might assume, so this one certainly passed the test of ‘singability’. And if it stayed throughout too close to the English folksong Scarborough Fair and strayed at the end a tad too near to We Three Kings of Orient Are, it remained – for better or worse – in one’s mind for some days to come.

The winner of Category 2 was Owain Park, a young musician based in the South West of England. He is currently the Senior Organ Scholar at Wells Cathedral, a position he holds until autumn 2013, when he will take up his place at Trinity College, Cambridge, to study music as one of the college organ scholars. His Let Christians all with Joyful Mirth sets words found in an old church gallery in Dorset. This carol relies too on a striking repetitive rhythm; it is the one Bernstein used for ‘America’ from his West Side Story, the composer marking it ‘Tempo di Huapango’. It would be churlish to criticise too strongly the music of such a young composer, and the harmonic thinking is remarkably mature, but the slight feeling of ‘stop and go’ may be put down to the organ accompaniment, which is interpolated into the formal scheme, dividing one homophonic choral block from the next. All in all it is more an anthem than a carol, and only possibly a useful addition to the repertoire, albeit a work that could be tackled by a small chamber choir whose own style is, like the piece itself, quite fleet of foot.

Dominic Irving won category 3. Based in the South-West of England, he holds an MA in Composition of Music for Film and Television from Bristol University, and a BMus in Composition from Trinity College of Music, London. His compositional style has been described as highly melodic, often humorous, and moves freely between bright virtuosity, rich lyricism and stern dissonance. To date he has completed a piano concerto, a children’s cantata, numerous choral works, some chamber music, and a number of film scores.

His carol Blessed be that Maid Marie was rendered in earnest manner by the versatile Quay Voices who – even if they were at the limits of their technique – understood well the composer’s tight control of dissonant structures. This is highly idiomatic choral writing that ebbs and flows as one acerbic harmony gives way to the next. A full triad appears just where needed, at key harmonic points along the way. The musical language is really not reminiscent of Britten, but the formal constraints are evidence of composer who, such as he, knows how to say exactly what he wants to say.

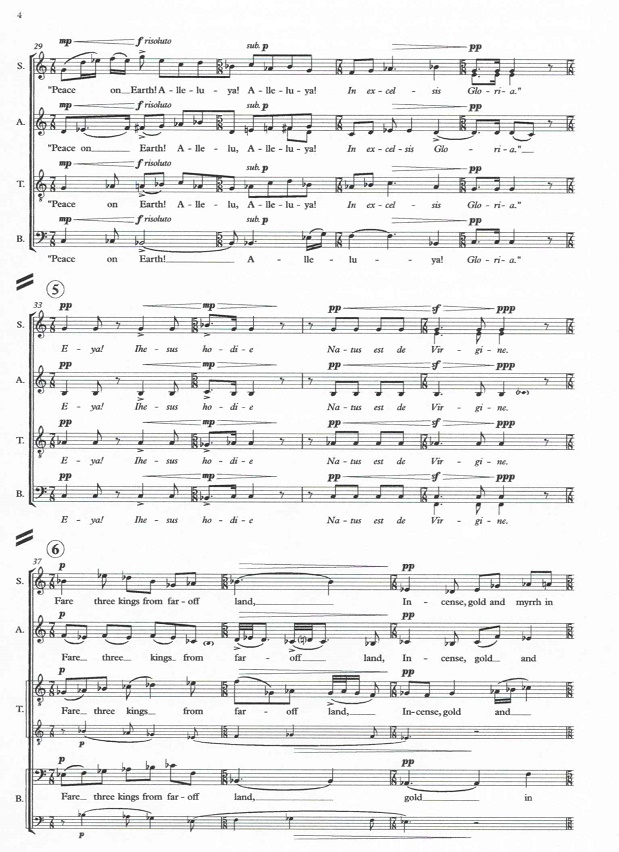

(Click on the image to download the full score)

The prize in the final category, a composition written especially for The King’s Singers, went to Steven Griffin from Edinburgh. A previous member of the Chapel Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied music under John Harper, Bojan Bujic and a former King’s Singer, Bill Ives, he is presently Assistant Musical Director at George Watson’s College in Edinburgh. Mr. Griffin began writing music at the age of age ten and since then his music has been performed at the Barbican Centre, the Southbank Centre, the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and St. Martin-in-the-Fields. He admits to taking composition seriously only having begun his career as a teacher, having found it difficult to find music that was, as he points out “easy enough for a young choir to learn but which was neither childish nor patronising towards children”. His carol A Hymn to the Virgin, a poem famously set by Britten of course, is to one of the competition’s prescribed texts. It is quite superb, and is “perfectly suited the incomparable style of The King’s Singers” as a tweet by the ensemble actually during the concert put it.

Commenting on the winners, Stephen Cleobury said: “The response to the competition was tremendous and it was very difficult to choose the winners. Overall the quality of entries has been exceptional.” David Hurley had this to say: “I am delighted to be involved with this competition and have thoroughly enjoyed working with Stephen Cleobury and John Rutter. The standard in all the categories has been great, and in the King’s Singers’ category we received many skilfully crafted works.” And Adrian Frost, speaking on behalf of the sponsors, praised those who established the competition, explained that: “There has been a lot of work done in the background to the competition. Those people who have helped to make the competition a success have seen their vision realised with the large number and quality of the entries.”

Many, it would seem, had given very generously and hope that the competition will be, as Mr. Frost says, “an inspiration to composers across the UK”. Whether or not it will become an international event remains an open question. But if the competition seriously wishes to promote the cause of the Christmas carol, it will need to address this issue and open up ‘A Carol for Christmas’ to all composers around the world, whatever their nationality.

As the audience inched its way out of King’s College Chapel just a few days before Christmas, the famous Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols imminent, discussions began about the new works performed, and the future of the carol as a species. With four categories and prizes divided between welcome remuneration, a possible publishing deal, and a radio broadcast heard by many, the competition is cannily structured. We just hope it will get the recognition it deserves and new forms of musical expression will be found within such a traditional genre.