After Eric: New American Composers after 1980 (part one)

By Philip Copeland, choral conductor and teacher

Eric Whitacre dramatically altered the landscape of American choral music in 1996 with “Water Night.” Since then, many of us have probably programmed his most popular works: Sleep, With a Lilly in Your Hand, Lux Aurumque, Leonardo. With his Virtual Choir project, he showed us the power of YouTube to touch the world with choral music, reaching millions of viewers. In a sense, the composer has had such an enormous presence in the last twenty years that it is difficult to think of others that have come after him.

This article seeks to highlight the emerging and significant American composers that have come after Eric Whitacre. These composers, born in or after 1980, have found traction in the quickly evolving world of composition for choirs: Ted Hearne (b. 1982), Jake Runestad (b. 1986), and Nico Muhly (b. 1981).

Ted Hearne (b. 1982)

www.tedhearne.com

Ted Hearne (b. 1982) is a highly respected composer, having received numerous fellowships, commissions, and opportunities to serve as artist-in-residence across the country. He recently joined the faculty of the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music as Assistant Professor of Music . His training includes study at the Manhattan School of Music and Yale School of Music.

Ted Hearne grew up attending choir rehearsals and has a self-professed “deep connection” to choral music. He has this commentary on choral compositions from the United States: “It’s unfortunate that so much choral music in this country conforms to expectations without a fight, fails to challenge thinking musicians and thinking audiences, and is generally so . . . bland.”

Hearne’s music is anything but bland; it is jarring. In fact, he brands much of his music as “Unsettlement Music.” His compositions carry clear social messages, whether you agree with his politics or not. This message is embedded in his music through his textual sources, achieved primarily through his non-traditional choice of text or his juxtaposition of textual sources.

Three of his works are highlighted with their textual sources here:

“Consent” (2014, 7 minutes)

Textual source: Love letters from two time periods, authored by composer and composer’s father, wedding rites from Catholic and Jewish traditions, text messages between two convicted rapists from the Steubenville rape trial.

“Consent” was composed as a response to the Steubenville rape trials, a case where text messages became an important part of the evidence against the young men responsible for the attack and cover-up. The composer writes, “when these text messages and other evidence were released, I think we saw an urge to use the language of these teenagers to separate ourselves from them ideologically; to disown them completely, cast them out as an aberration, rather than to own them and their actions as an understandable product of our culture and the messages it sends.” He continues, “Consent was an attempt to ‘own’ those teenage rapists, and accept them as part of a shared problem. It got me thinking about the (very recent) history of marriage as a primarily financial/economic transaction that treated women as property . . . it also got me thinking about all the corruptive messages I myself have absorbed — from the culture, from my own father — and how they may be reflected in my own language. I set the text in a way that obscures and conflates their surface meanings and puts them forward in a way that makes all the messages part of a running current of ideas.”

Ripple (2012, seven movements, 10 minutes)

Textual source: This work uses as its text a single sentence from one of the 400,000 internal military cables known as the Iraq War Logs.

“Ripple” uncovers the deeper emotional implications buried in a generic military report into the extremely emotional elements embedded in the sentence. The text is from a log entry that describes an incident when an American military officer opened fire on an unidentified vehicle that was driving toward a checkpoint in Fallujah: “The marine from Post 7 was unable to determine the occupants of the vehicle due to the reflection of the sun coming off the windshield.” The occupants were a family of Iraqi civilians – a mother was killed, her husband and two children badly injured.

Privilege (2009, five movements, 14 minutes)

Textual sources: composer’s poetry, an interview with David Simon on Bill Moyers Journal, and a traditional Xhosa anti-Apartheid song

The texts of “Privilege” highlight the darker side of capitalism, especially its impact on the plight of inner city youth and society’s response (or lack of response) to the problem. In the first movement, the composer pens his own question to society, asking if anyone really cares about the poor, or whether they prefer to shut their eyes to the realities that are ever present. The second movement quotes David Simon and his description of capitalism as a one-armed winning slot machine that deceives people into thinking that everyone wins, a situation the composer likens to a “flashing window, empty street, and burning TV song” in the third movement. David Simon’s words appear again in the next movement with a damning judgment on society: “we pretend to need them . . . to educate . . but we don’t . . . and they get it.”

Of these three works, “Privilege,” is the most accessible composition for many choirs, although it is far from the most acerbic in message. It was commissioned and premiered by the San Francisco choral group “Volti” and Robert Geary in 2010.

As an example of Hearne’s compositional style, I will highlight a few excerpts from Privilege that show a musical depiction of the social message:

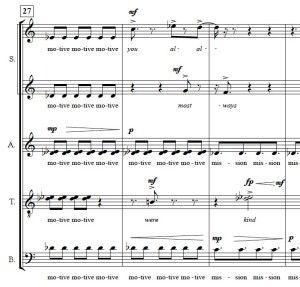

Example 1, Privilege, “Motive/Mission,” m. 12-15.

Hearne understands the profound commentary he can make on philosophical concepts with the simplest of musical gestures. In this example, he shows how our motives and our missions, although similar in nature, do not line up.

The differing rhythmic patterns, born of philosophical need, are difficult for many conductors and musicians.

Example 2, Privilege, “Motive/Mission,” m. 27-29.

On top of this disjointed motive/mission statement, the composer delivers his message “you were almost always kind” in staggered entrances by voices in different sections. This method of text declamation, reminiscent of Schoenberg’s Klangfarbenmelodie, is very effective. He also seems to suggest a duplicitous meaning when he provides a two-part dissonance on the word “kind.”

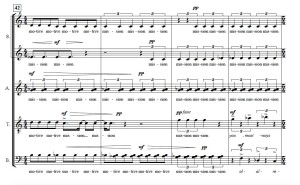

As the first movement progresses, the rhythmic complexity increases, shown in m. 42-45 (Example 3).

Hearne’s music is complicated; he requires independent singers of very high quality.

Example 3, Privilege, “Motive/Mission,” m. 42-45.

| © Ted Hearne: all rights reserved |

Jake Runestad (b. 1986)

www.jakerunestad.com

Jake Runestad, from Rockford, Illinois, is one of the brightest stars among young composers in the United States. He has had extensive training with acclaimed composer Libby Larsen and holds degrees from Winona State University and the Peabody Conservatory of Johns Hopkins University.

Although not yet thirty, he has received prestigious commissions from Seraphic Fire, VocalEssence, the Master Chorale of Tampa Bay, and Cantus. Runestad’s music is performed often at conferences of the American Choral Directors Association. At the most recent National Conference in February 2015, five choirs performed three works: Alleluia (by Salt Lake Vocal Artists and University of Southern California Thornton Chamber Singers), Nyon Nyon (by Baylor University and Waukee High School) and I Will Lift Mine Eyes (by Seattle’s Choral Arts).

Jake’s success has enabled him to compose full-time. He has a beautiful web presence; his fluidness with technology has allowed him to take advantage of the financial benefits of self-publishing and digital distribution.

This online connection allows the composer to have an immediate and potentially intense personal connection with each conductor. In his words, “With each order, I have direct contact with my customers and can answer questions about the works, rush orders (often within minutes), set up video chat sessions with choirs, provide practice tracks, and foster meaningful relationships with ensembles around the world.”

Two works are featured here: Nyon Nyon and The Peace of Wild Things.

Nyon Nyon (2006, 3 minutes)

One of Runestad’s most popular works is Nyon Nyon, a work that the composer described as an “exploration of the effects that one can produce with the human voice.” It is a driving and exciting piece of music that incorporates a number of unique sounds that are similar to a flanger, wah-wah pedal, drum and bass, and synthesizer.

The work has a driving rhythm and excitement from the first few notes, and then has a synthesizer-like glissando in both voices; it captures the listener immediately. (Example 4)

Example 4, Nyon Nyon, m. 1-3.

One of the more electrifying moments in Nyon Nyon comes at the “Techno beat” portion of the piece. (see Example 5) The bass singers become an electronic tech drum, the tenors sound a drone, and the rest of the choir scoops and slides with ooh’s and ah’s. (Example 5)

Example 5, Nyon Nyon, m. 27-28.

The Peace of Wild Things (2012, 4:30 minutes)

Runestad forges intimate connections between words and music. He describes the process of setting text as “trying to find the music that the poem has intrinsically inside it.” One of his accessible works of this type is The Peace of Wild Things, a piano-accompanied setting of environmentalist Wendell Berry’s famous text by the same name, a work that won the Grand Prize in the 2014 YNYC Composers Competition.

As beautiful and profound as Berry’s poem is alone, Runestad’s setting provides a new dimension to the words and enhances the message. The composer gives most of Wendell Berry’s words to the bass section; the rest of the choir provides an attractive harmonic background and occasional emphasis to the text. He adds power to each line of the poem and creates a radiant refrain by repeating the text “for a time, I rest in the grace of the world.”

Example 6, The Peace of Wild Things, m. 51-54.

The work’s accessibility does not diminish its quality; Runestad has created a deeply intelligent setting of the philosophical text; the music is haunting and memorable.

Jake Runestad is a prolific composer of choral music. Other high quality works to explore are his “Alleluia,” “I Will Lift Mine Eyes,” “Why the Caged Bird Sings,” and “Spirited Light.”

| © Jake Runestad, JR Music. jakerunestad;com |

Nico Muhly (b. 1981)

www.nicomuhly.com

Nico Muhly’s recent splash in the opera world with Two Boys put his name on the lips of many in the classical music world. The opera’s subject matter, about the stabbing of one teenager by another, was called “a compelling opera for our time inspired by real-life internet crime” by author George Hall of The Guardian. It is a work that highlights the composer’s interest in diverse subject matter, sounds, and ideas to the world of classical music.

When it comes to choral music, the composer is heavily influenced by the English school of composition. On WQXR’s “Obsessive Choral” series, hosted by the composer, Muhly shared that “Choral music is my first love. Even though my voice broke in 1994, I still return to the emotional landscapes of Byrd, Tallis, Gibbons, Howells and Britten as a sort of home base for all of the music I write.”

Many of the choral works by Muhly show evidence of these great English composers, especially Britten.

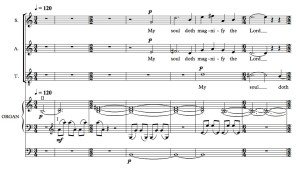

First Service (2004, 9 minutes)

Muhly’s First Service was composed when the composer was just twenty-three years old, but it reveals a subtle complexity and maturity that one would expect from a composer more advanced in years. The First Service sets the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis and follows in the tradition of William Byrd and Charles Stanford. The composer describes the opening organ motive of the Magnificat as a symbol of one “nervously twitching in anticipation” in a marvelous portrayal of an expectant mother in the most unusual of circumstances.

Example 7, First Service (Magnificat), m. 1-7.

There are several layers to this work. It is interesting to notice the slow pedal point type stasis in the lowest notes of the organ pedal as a foundation for more frenetic organ twitching while the choir proclaims the text. The sopranos highlight the prophetic message of the text, with occasional dissonances on the jarring philosophical ramifications of Mary’s pregnancy. (Example 8)

Example 8, First Service (Magnificat), m. 26-30.

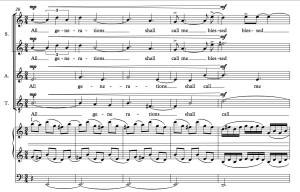

At appropriate moments, Muhly shows creative skill in his setting of “he hath shewed strength with his arm” through dissonance and voice leading. (Example 9). It is interesting to note his use of dynamics in this section, asking the voices to enter loudly and then soften as each successive voice enters.

Example 9, First Service (Magnificat), m. 66-71.

| First Service (Magnificat & Nunc Dimittis) – Biblical Text -Music by Nico Muhly © Copyright 2006 Chester Music Limited/St Rose Music Publishing Co. – Chester Music Limited. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured – Printed by Permission of Chester Music Limited. |

Bright Mass with Canons (2005, 13 minutes)

To date, Muhly has listed fourteen choral projects on his website, with fewer works listed in recent years. His Bright Mass With Canons (2005) is another organ-accompanied work that features some moderately advanced organ writing and more accessible writing for choir.

Example 10, Bright Mass with Canons (Sanctus), m. 195.

In the Sanctus, Muhly features some senza misura sections as a harmonic background to a canonic statement of “Dominus Deus Sabaoth,” shown in Example 10.

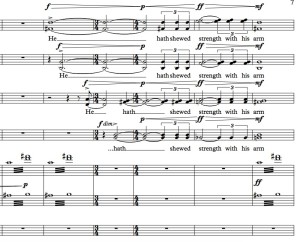

Muhly concludes his Bright Mass with a haunting setting of the Agnus Dei. He features paired voices in canon, with sparse accompaniment by the organ. (Example 11).

Example 11, Bright Mass with Canons (Sanctus), m. 278.

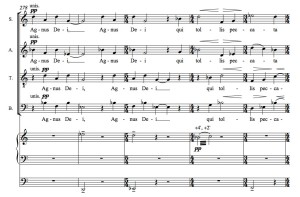

Towards the end of the Agnus Dei, Muhly places the choral voices in long notes and adds a soprano solo that emerges from the choir in a final pensive plea, setting the text “Agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi” while the choir sings “Dona nobis pacem.”

Example 12, Bright Mass with Canons (Sanctus), m. 285-287.

| Bright Mass With Canons – Words & Music by Nico Muhly © Copyright 2005 St Rose Music Publishing Co/Chester Music Limited – Chester Music Limited. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured – Printed by Permission of Chester Music Limited. |

Hearne, Runestad and Muhly do not come close to encompassing the diversity of choral composition occurring in the United States in the time period after Eric Whitacre. They are, however, very bright stars.

As a part of researching this article, I polled choral professionals on Facebook and ChoralNet and I was introduced to many composers whom I had not heard of and was impressed by their accomplishments and creations. Several of these composers will be featured in the second part of this article, planned for July 2015.