The Art of Singing One Voice to a Part – An Occasional Series of ICB Interviews

By Jeffrey Sandborg, Director of Choral Activities and Wade Professor of Music, Roanoke College

The Hilliard Ensemble: Interview with David James and Gordon Jones

Jeffrey Sandborg: Are you both founding members?

David James: I’m the only one left of the original four.

Gordon Jones: And I’ve been with the group since 1990. Over twenty years, now.

JS: Does the Hilliard Ensemble comprise your full-time work?

GJ: There’s not time to do anything else.

DJ: As a group we occasionally do a master class and what have you. None of us has a separate job; this is our bread and butter.

GJ: We do up to a hundred concerts per year, plus recordings, plus various other projects, along with keeping up the website.

JS: With your heavy performance schedule, how often do you rehearse?

DJ: That’s difficult to answer. We don’t have any set rehearsal patterns. The best way to describe it is that we rehearse when we need to.

GJ: That’s very good for us because there’s nothing worse than rehearsing when we don’t need to. We need to learn a lot of new music written for us so we arrange rehearsals for that. However, if we’ve got a period where we’re singing standard repertoire and we haven’t got anything new we’ve got to learn, then we probably won’t rehearse much, it’s as simple as that.

DJ: We don’t say, “we must rehearse this week,” because the fact of the matter is that we do sing so many concerts that we tend to do our rehearsing and learning when we’re on the road. With so much time together travelling, we find that this is generally enough and, so, when we’re at home, we try to keep rehearsals to a minimum.

JS: How many different programs will you cycle through in those 100 concerts?

GJ: We have quite a lot of regular, fixed programs. There must be at least ten programs we do regularly, maybe more. But on top of that there are a lot of one-off programs for festivals or other performances that have a special theme. If we have a big, new work written for us then that’s an entirely different kind of program. In all we get through an amazing amount of repertoire.

JS: Since you sing so much newly commissioned music, how would you describe your process of learning a new work?

GJ: The motto is, little and often. I think we’re happiest learning a new work when we’re on tour because it means we can spend maybe an hour on the piece every day in a hotel room, rather than try to meet up in, say, London. To make a rehearsal worthwhile you’ve got to rehearse three hours and three hours on a new piece is too much. Your brain starts aching. We find that things fall into place much better this way.

DJ: It’s an extraordinary thing the way the process works and if you were to ask, “Why is that?” I can’t answer. It seems to me that a little time is an amazing developer of music learning. Something we might have looked at for an hour yesterday will seem easier today. Strangely enough, this will almost always be the case.

GJ: Very often we’ll have difficulty with a progression in a new piece of music. There may be just one chord that’s not working and you can’t get from A to C through B because B isn’t in the right place. We’ll sometimes struggle with that for a little while. It’s not necessarily obvious which of the pitches need adjusting.

JS: This occurred to me when I heard you in concert with Garbarek. What if a piece slips a quarter tone and the sax comes in at what for him is still his fixed pitch? Does that happen?

GJ: There are times when you have to negotiate with him, for example, when his reeds aren’t behaving themselves. You’ll hear that he’s playing very quietly and you’ll think to yourself, “Is he worried about pitch?”

DJ: A large amount of the time we’re able to stay in tune. We know the important notes within the harmonies to keep absolutely right. And Rogers (Covey-Crump) has such a fantastic ear for pitch. You know that if you home in on what he’s singing, it’s going to be OK. I repeat myself but it’s all a matter of listening, of knowing what a chord sounds like when it’s in tune.

GJ: I have to admit, we have preferences for keys. We’re not very good at singing in sharp keys. I don’t know why certain preferred keys are most comfortable.

JS: When you’re working on a commission, do you include the composer in that process?

DJ: Not so often. Normally, they’re not around but we find it works better when we work on it ourselves. Maybe closer to the performance, and then maybe they can make some comment or adjustment. On the whole we find this way to work better. They trust us. We’ll get as close as we can and it might satisfy them completely. If we’re uncomfortable with anything, we can always get on the telephone or write an e-mail.

GJ: Sometimes, after looking at the score, you’re baffled because things are not immediately obvious. There may be notes we simply cannot sing! Before the process begins we send out information on a piece of paper with all of our ranges on it and it’s amazing how many composers ignore it.

DJ: And we’re not so keen on receiving the score where it is so tightly marked with every bar having dynamics. When that happens there is very little for the performers to decide.

JS: So, when you get the score, nobody sits down, analyzes, makes decisions, plans a rehearsal? You just have at it?

DJ: Usually. When we get the new score we go through what we can in rehearsal. At the first meeting it is pretty clear how much time it’s going to take, how difficult it is, and how we’re going to have to approach it.

JS: Do you have a coach or some other objective set of ears that might give you feedback on your overall sound?

GJ: No. Sometimes I think I could see the point in that but other times I think it would be nonsense. We have our ‘house style’ which is the four of us.

DJ: We think that Rogers is enough in terms of tuning. And for a cappella it would not be useful. We’re very fluid in what we do and, therefore, someone from the outside wouldn’t quite work because at every performance we’d start to think what we’d been told and we’d lose that sense of freedom.

JS: I see from some of your recordings that you expand the ensemble for certain repertoire. What’s the largest the Hilliards could be?

GJ: Eight, maximum. We have a pool of friends who are fabulous singers and they are very happy to join us when we need them. We don’t really go outside that circle because we like to sing with people who know how we sing. Since we don’t have a conductor, someone who doesn’t know how we work can become quite nervous and might wonder, “What’s going on here?” We don’t show them how it goes; you just have to guess.

GJ: It takes a little while for people to get used to working this way. New people are quite often very uncomfortable at a first rehearsal. We’re just expecting them to do what they feel like doing and we’ll react to it.

JS: What happens when you’re on tour and someone cannot sing because of illness?

GJ: We have some emergency three-voice programs, depending on who is sick.

JS: I wonder about these pieces you perform with saxophonist Jan Garbarek introduced with the Officium project? How did that come to be?

GJ: It came about through our record company, ECM, which has always fostered collaborations between its artists. It just happened that if we were going to have this sort of collaboration, Jan was the right person. A wind instrument is much more vocal-sounding, as opposed to a piano which for us is difficult to work with. First, because the piano is a percussion instrument and second because the tuning is crazy for us.

DJ: Of course we were apprehensive when we first met—no one knew what to expect. I’m sure Jan felt the same way. So the first meeting was a nerve-wracking experience. Fortunately, at the first very meeting it was clear that there was common ground. He somehow understood how we sang and felt comfortable to join in, and vice versa. It didn’t seem so different from what we do. And so, from the start both sides were reasonably comfortable.

JS: There seems to be a lot of this kind of ‘improv’ – that is, improvising over fixed-pitch choral works – going on in Sweden and Norway, and also the practice of using the space in creative ways by moving around. Did Gabarek bring these ideas from Norway?

GJ: Well, the moving around in space may actually have come from us.

DJ: I think that initially it took Jan some time to get used to the idea that he could move around, especially since he’d always been onstage with his band. Suddenly, he thought, “Gosh, in the right building, this is good because I can create different colors.”

GJ: And then we tried to push the boundaries to see how far apart we could stand and still sing the same piece of music.

DJ: In the initial recordings Manfred Eicher, the producer at ECM, said, “Guys, why don’t you go to all four corners of the chapel and sing into the walls?” We thought, “The guy’s completely mad.” But somehow it worked—again, it’s the listening. It’s like learning anything new, awkward at first and then normal after you’ve done it awhile.

GJ: Fortunately it was only an extension of what we were already doing because we work entirely by listening. It was just a matter of having the confidence of singing with someone twenty meters away.

JS: Why do you think that audiences have such a strong response to this spatial music?

DJ: It is noticeable that people are most taken by our moving around and singing amongst them. They can’t quite believe what is happening. Of course, it needs a decent building. People suddenly feel that they’re part of the music. I’m surprised it’s not done more.

JS: Where does all of this music come from and how do you handle editions of so much rarely performed music? Do you make your own?

GJ: Generally we don’t make our editions but just occasionally we have to. There are all sorts of different ways of coming up with scores. The Armenian music we sang in our last concert was sent to us from Armenia because they were preparing a special new edition of the complete church music of Comitas (1869-1935) and they wanted us to sing some. So that was a gift. I might find stuff in libraries or on the Internet and all sorts of curious places. Something I sang on my own the other night is written in Kiev chant notation. It was the only version available so I had to find out how to transcribe it.

JS Do you ever sing, for example, something like Brahms?

GJ It gets very difficult, then, because in a four-part Brahms piece you’ll have a high voice, slightly lower voices, then a lower voice, then the bass. In our group, we have a high voice, two equal middle voices and the bass. So Brahms requires a very different disposition than our ATTB. To do Brahms it would mean that one of the tenors would have to pretend to be an alto and you’d probably have to transpose the piece because the other tenor is probably going to be too low.

JS: Does most of this early music conform to your forces, ATTB?

GJ: A lot of it but not all. There’s a whole slew of English church music that lies very differently, with high boys’ parts, for example.

DJ: A lot of it is determined by how we sing. We try to sing with a very straight tone most of the time and that suits well the Medieval and Renaissance periods, I think. Our voices are not so naturally suited to the Romantic.

JS: What drives your programming now? Recordings? Commissions? The marketplace?

GJ: Very often it’s got to do with a new acquisition. We might get a piece written for us that’s so good that we see the possibility of a good program built ‘round it. One recent program was done because of that. We had a new piece by Roger Marsh, a setting of Dante, and I developed an all-Italian program to go with it. It became a mixed program of early and contemporary music with an Italian theme. Every so often we’ll think there is some music that needs doing, or else we’ve got something particular we want to record.

DJ: Mainly our programming is determined by things we like to do. We don’t go by the marketplace. And we’re not ones looking to see whose anniversary is coming up; that’s not our way at all.

JS: How did you come to specialize in early music?

DJ: I first started to sing when I came out of Magdalen (Oxford). This whole early music movement hadn’t really started then and I briefly joined a group, The Early Music Consort of London, led by David Munrow (1942-1976). David was blazing a new path. The interest in early music really started instrumentally. It was only later the vocal came along. He was the first who one day said to a few guys, “Look, shall we try some of the vocal stuff?” I was invited to join in and so was Rogers, coincidentally. David was magnificent. He quickly realized that the voice didn’t work quite so well with instruments so he wondered, “Why don’t we try a cappella?” And we tried some Renaissance pieces and it was a revelation; we were completely bowled over. Sadly, David’s life ended very tragically within six months of starting so we were left with a huge hole.

JS: Did the group thrive within the early music movement and then expand into new music?

GJ: The group has done new music from the very start.

DJ: With the very first concert, actually. In those days record companies wouldn’t take much risk with contemporary music so, although we did it in concert, it wasn’t recorded. The first time we came to the public’s conscious was with Arvo Pärt. That was through ECM.

GJ: The Hilliard Ensemble did the first performance of his Stabat Mater.

JS: What projects do you have on the horizon?

DJ: We find there are still challenges with the small world in which we work.

GJ: And we have some new pieces being written for us.

DJ: There are pieces being written either with small chamber orchestra or for large orchestra which is quite exciting. We’ve also got quite a nice project in a couple years’ time—we’re joining with a viol consort, Fretwork. We’ll be singing Orlando Gibbons’ The Cries of London and at the same time, we’re commissioning a new composer to write on the same text. That’s the sort of thing we’re doing— but there’s no new ‘Officium’ on the horizon!

GJ: We also are working on a theater project, a piece called, I Went to the House but Did Not Enter by Heiner Goebbels. We’ve done this piece a lot in Europe.

JS: What do you mean when you say “theater piece”?

GJ: It’s staged with costumes and it’s just the four of us.

DJ: It’s superb. He wrote it specifically for us so we worked with him from day one. We were very much part of the whole creative process. Goebbels’ background is the theater but he’s taken a tremendous interest in music and he has a phenomenally wide, catholic taste for all types of music and theater. He’s a visionary. He can see things not many others can imagine. And he can see what works and how to put things together. That’s what he did with us.

JS: Is it recorded?

DJ: There might be a DVD one day.

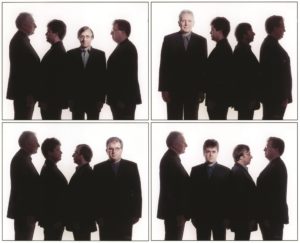

Since its founding in 1974 The Hilliard Ensemble has been at the vanguard of both the Early Music movement while also performing and commissioning new works. Consequently, its vast discography has brought to light much important repertoire for audiences and conductors. Comprising four male singers, David James, Countertenor, Tenors Rogers Covey-Crump and Steven Harrold, and Gordon Jones, Baritone, ‘The Hilliards’ maintain an ambitious performance schedule of nearly a hundred concerts every year. The ensemble’s profile was raised with its immensely popular crossover recording ‘Officium’ (1994) with saxophonist Jan Garbarek. It combined Medieval and Renaissance motets with improvisation, and the collaboration between these artists continues to be fruitful with the most recent ‘Officium Novum’ released in 2010. Arvo Pärt is only one of the numerous living composers with whom the Hilliards have worked closely. In addition to being a rich source for further information about the ensemble, the Hilliard website has informative articles on tuning by member Rogers Covey-Crump. Web site: http://www.hilliardensemble.demon.co.uk