Basic Cognitive Processes in Conducting

Theodora Pavlovitch, conductor and professor

Psychological processes represent a basic category of phenomena, or in other words, a sequence of changes of the mental activity upon certain interactions between a human and the world. They are dynamic forms of reflecting reality, which according to their nature are differentiated as:

- Cognitive psychological processes – sensations, perceptions, thinking, memory, imagination;

- Emotional processes – sensations, active and passive experiences;

- Processes of will – will, resolution, effort, performance[1].

Studying the specificity of cognitive processes in the course of performing an activity so complex and diverse as conducting will help us reveal an important part of the relevant psychological characteristics.

- SENSATIONS, PERCEPTIONS AND CONCEPTS

А.) Sensations

Sensations are the most elementary cognitive processes. They reflect the individual properties of the objects and the phenomena from the internal and external world upon their immediate impact on analytical data. Their function is to secure more complex cognitive processes. According to the nature of the reflection and location of the receptors, sensations are divided into three groups:

1) exteroceptive (“external”), which reflect the properties of the objects and the phenomena of the external environment, through receptors, located on the body surface; this group includes visual, aural, olfactory, temperature and tactile senses;

2) interoceptive (“internal”), which reflect the status of internal organs, through receptors in the internal organs and tissues; this group includes all organic sensations, including the sense of pain and balance, etc.;

3) proprioceptive, which provides information about the position and movement of the body through receptors located in the muscles and tendons[2].

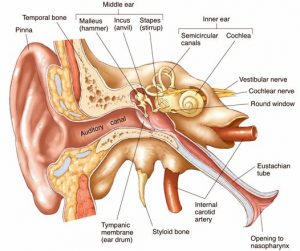

Aural sensations are of major significance to the first group, exteroceptive sensations, as well as to all types of music-related activities. Visual sensations are also important as they allow the conductor to get information from the music score as well as about the activities of the performers’ staff during the performance.

The role of interoceptive sensations is not basic but they are important for the general physical condition of the conductor. Therefore, they have an impact on the level of higher psychological processes such as emotional, will, memory, imagination, etc. A specific example in this regard would be the words of Karajan who said in an interview: “My joy from conducting is much higher and maybe the audience feels that. The orchestra positively feels it. My joy from conducting has acquired new dimensions since I got rid of the severe pain I experienced for a full eight years”[3].

Concurrently this practice has proven that the intensive functions of consciousness and subconsciousness in the creative process may neutralize interoceptive sensations. Further Karajan said: “Once during a concert, I passed a kidney stone and I noticed it after that. Usually, this is a pain that makes you roll on the floor”[4].

With regard to proprioceptive sensations, which were highlighted in the previous chapter, kinaesthetic senses are highly important in conductions, as they give information about the position and the movements of the body and its individual parts. This shall also include sensations from the vestibular apparatus regarding body balance in a certain space. Kinaesthetic sensations allow conducts to perform specific, purposeful and efficient movements when there is a sufficient degree of self-control. Many conductors by way of self-monitoring come to conclusions about the need for muscle “freedom”. Lorin Maazel said: “Muscle tension is the hardest to overcome. Once I got into music, not only did my arm and shoulder muscles strain but so did my back and leg muscles. One day I told myself: You have to learn how to relax…”[5].

In this regard, interesting thoughts are found in the Handbook of conducting by Hermann Scherchen: “There is a law – the intense mental energy comes in the form of intense physical energy. However, physical energy is anti-musical on its own: Music is an art of the spirit and spiritual tension, it does not stand the physical energy, which has an end in itself”[6].

The conclusions of K.S. Stanislavski, resulting from his observations on the actor’s work, are very valuable: “As long as there is physical tension, there can be no proper, sensual feeling and normal spiritual life. So, before he begins creating, one must prepare his muscles, so that they do not limit the freedom of movement”[7].

The problem of muscle freedom has a largely individual character – many conductors achieve this freedom in a natural way, without needing special care. On the other hand, as we saw in the citations, even the most famous conductors have had difficulties in overcoming muscle tension during their career. It is important in this case to teach young conductors about proper muscle movement, i.e. activating kinaesthetic sensations and conscious self-control to remove all types of unnecessary tension.

This issue has been thoroughly studied in the scientific work of A. Sivizianov “The issue of muscular freedom of the choir conductor.” Here the author develops a comprehensive theory for the way to achieve motor freedom in the process of conducting based on many scientific studies.

As previously mentioned, kinaesthetic sensations are directly connected with musical-aural perceptions during conducting. In order to reveal the mechanism for creating these perceptions, it is necessary to look at the role of aural sensations and perceptions.

According to basic qualities of tone such as acoustic events, 4 types of sensations are revealed: Height of pitch, strength, timbre, rhythm [8]. This differentiation has a pure scientific value, as in practice the four features of tone are fully connected and constantly overlap with each other. Reviewing them separately is required for a deeper analysis. Before that, we must clarify that due to the complexity of the processes in the sound analyser, scientific literature uses the term “sense” more often, which more so encompasses the psychological, rather than the physiological part of the phenomenon. And so, without stopping on the psycho-physical mechanism, we will track the role of the various components of musical sense in conductor activity.

PITCH HEIGHT SENSE: this tone sense is considered essential for musical capabilities[9]. It has been proven that it may be improved with training, which certain scientists have argued in favour for. Further, it is underlined that this sense is important but not absolutely sufficient for musicality.

Tone sense has great significance in the practice of conducting due to the need to control and indirectly invoke corrections of the tone of multiple sound-producing objects (instruments, voices). In this case, descriptive ability is of great importance as it allows sensing even the smallest change in the height of pitch.

On the other hand, the theory of the zoning nature of human hearing clarifies the ability to perceive deviations from a tone only above specific values at the rate of 20-30 cents[10]. It is exactly this specificity of hearing that explains the “choir effect”, which is typical for all kinds of performing ensembles. Due to the inability for multiple performers to reproduce a tone with absolutely the same pitch in ensemble performances, combined tones are produced, the height of which corresponds to a narrower or wider zone of sound frequencies. The purpose of the conductor is to greatly control the width of that zone and to ask the performers to make relevant tone corrections if there are deviations exceeding a specific value or when the combined tone is not perceived as a whole. A specific case in this regard is playing or singing a wrong tone (due to the performer’s mistake or an error in the sheet music) and the conductor has to exercise tone control. To carry out this task, the conductor should possess and develop their sense of tone allowing them to perceive and respond adequately to the occurring tone deviations.

TONE STRENGTH SENSE is important for conducting due to the primary significance of the dynamics for the musical interpretation. Dynamic sense appears early on and is easily controlled. The high degree of development of this sense is another compulsory condition for conducting work due to the need for a high distinguishing ability with regard to the different degrees of dynamics. An extraordinary example in this regard is part II of the composition Inori of Karlheinz Stockhausen where the conductor, as instructed by the author, must achieve 60 different degrees of dynamics.

One of the biggest problems of dynamic sense upon conducting is the effect of masking or deafening, i.e. “hiding” one tone behind another which especially occurs in tones with close pitch. This specificity clearly also shows the direct interrelation between tone sense and dynamic sense. In addition, dynamic sense is directly connected with timbre sense where the human ear perceives some timbres as “stronger” than others due to their spectral characteristics. A good example of this is that of two of the Ten Golden Rules for the Album of a Young Conductor by R. Strauss. He says: “5. But never let the horns and woodwinds out of your sight. If you can hear them at all they are still too strong; 6. If you think that the brass is now blowing hard enough, tone it down another shade or two”[11].

The dynamic sense of the conductor is of great importance for ensuring the dynamic balance of the performing staff, which represents an essential component of the overall choir or orchestra sound.

The lack of aural control caused by weak dynamic sense would cause significant damage to the structure of the musical interpretation.

TIMBRE SENSE is also of great significance in the practice of conducting. Due to the specifics of their work, a conductor must be able to perceive and indirectly impact multiple different timbres. According to the research of the Russian psychologist B. Teplov, three groups of signs are used to specify timbres:

- light features: Light, dark, glossy, matt, etc.;

- Sensory features: Soft, rough, sharp, dry, etc.;

- Spatial – volumetric features: Full, empty, wide, solid, etc.[12].

These features and any other similar ones are used often in conducting. The special importance of timbre and dynamic sense is due to the fact that they are of great significance for building the structure of music interpretation by having a detailed attitude to the dynamic and timbre components of sound.

RHYTHM SENSE is based on the conditional reflexes of time, which are fundamental for the central nervous system. The aural and the kinetic senses are combined for all types of musical activities (composition, performance, listening). Due to the important role of the locomotor apparatus for conducting, this combination is of primary significance. However, it is necessary to examine the more complex structure of rhythm sense, which is connected with the higher cognitive processes, separately.

As we already noted, the complex action of the listed types of sensations forms musical perception.

B.) Musical perception

Perception is determined as a basic mental process of subjective reflection of the objects and the phenomena from the reality in the totality of their properties and parts upon their immediate impact on the sensory organs[13]. Therefore, perception gives information about the integrity of individual aspects of objects and phenomena, unlike sensations, which give consciousness information about them. Concurrently “normal perception” is not a purely passive, meditative act, but also an active reflection. Eyes, ears and other body parts don’t perceive in isolation, but as part of a specific human being with a particular attitude to the perception who has needs, interests, pursuits, desires and feelings. Perception is not a mechanical sum of individual sensations but a brand new step of sensory knowledge with its specific features”[14]. Due to the complex structure of perception, differentiating its distinct types is carried out depending on the prevailing active analyser. On this basis, perception is divided into categories such as visual, aural, etc.

- AURAL PERCEPTION: in addition to the combination of different types of aural sensations, aural perception possesses a brand-new level of features, among which the following are of great significance for conducting:

- The perception of the melody as a complete musical thought, most often a carrier of the basic musical content or “melodic hearing”. Aside from external signs – height, durability, timbre and strength of the individual tones, an individual perceives melody in its entirety and the emotional information it carries. Melody cannot be perceived as just a physiological agitator; in this connection, B. Teplov states that such “absolute non-musicality is impossible for the regular psyche”[15].

When conducting, melodic hearing has an important function due to the fact that melody is one of the main forms of expression and its active perception (resp. modelling) is a significant element of the creative process. It is important for the conductor to perceive and, based on their perception, to influence the process of musical interpretation on forming the structural components of melody (intonation, rhythm, mode relations). At the same time, emotional perception and the experience of these components in their connection is also an important part of this process.

- The perception of harmony or harmonic hearing expresses itself as the “ability to perceive multi-voice music”[16]. As a result of multiple studies, it has been proven that this is the last developed ability of Man (in an ontogenetic and phylogenetic meaning)[17].

The significance of harmonic hearing in a conductor’s activity is undeniable. We can claim that the work of the conductor is impossible without properly developing this complex perception. Given that the conductor “operates” with multi-voice music in all its forms, he could not execute the creative process without the active perception of the “vertical”.

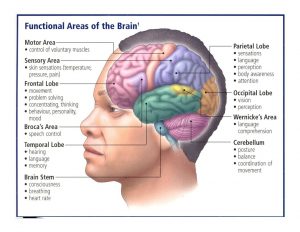

One of the main specifics of conducting for performing groups, including human voices (choirs, vocal-instrumental and vocal ensembles), is the presence of lyrics, which complicates perception even more, as they add lyrical information systems to the musical structures. With them, the mechanism for perception is connected to other brain centres (in particular, the speech centre). Therefore, we can assume that the whole process of perception is further complicated. In this mechanism, four levels of perception can be differentiated: phonetic – tone – phoneme level, morphological – motive-word level, syntactic – phrase – sentence–level and logic – composition, regarding the complete musical form and according to the meaning and text structure.

- VISUAL PERCEPTION – based on the conclusions made in chapter four on the role of the visual analyser when conducting, we can determine two types of visual perception:

- visual perception of the musical score, which is directly connected with aural perception and the created musical – aural perceptions:

- visual perception of the performers; also directly connected with aural perception. It ensures additional information when carrying out the creative process.

Weingartner states: “If the conductor is connected to the musical score in such a way that he/she cannot break apart from it for even a minute, to look at the orchestra, then he/she is nothing but a tact measurer, incompetent and has no right to call himself/herself an artist”[18]. In any case, this type of visual perception is directly dependent on the activity of memory, whose particularities during conducting we will look at later.

Both types of visual perception play an important role in the whole psychic process when conducting.

- THE PERCEPTION OF TIME: this is a “particular form of perception that reflects objective continuity, change and structure of the events that occur in our daily lives”[19]. It has been proven that hearing and motor sensations help for the most appropriate perception of time slots that are determined by rhythmic processes in the human organism i.e. heart rhythm and breathing rhythm. As an art that develops in real-time, the perception of time in music is of utmost importance.

When executing the creative process, time perception has two aspects for the conductor:

- regarding the sense and resp. perceptions for metro-rhythm through establishing conditional reflexes for time;

- regarding the perception of tempo, which is one of the most important forms of expression in music. As a main form-creating factor, tempo is of incredible importance for creating musical structure and not coincidentally, almost all great conductors in their written materials have examined the issue of “correct” tempo.

Conductors, from Berlioz, Wagner, Weingartner and Furtwängler to current conductors, constantly examine this question, as they seek objective criteria for determining tempo. Some of them even reach the conclusion that the perception of tempo is largely a psychophysiological problem, which creates a connection between the sense of tempo and the conductor’s temperament. Berlioz, for example, states: “The most dangerous ones are those lacking activity and energy. They cannot handle a faster tempo. As fast the work may start, if left to their care, they will slow it down until the rhythm reaches a certain level of calmness, apparently corresponding to the speed of their blood movement and the overall exhaustion of the organism… There are people in the cusp of their youth with a lymphatic temperament – as if their blood is circulating in a moderato tempo”[20].

Especially attractive, but proving the complexity of tempo perception, are Eugene Ormandy’s quotes, recorded by his orchestra performers during rehearsals: “During every concert, I keep feeling some uncertainty in the tempo. It’s shown clearly, quarter equal to 80, not 69″… “I conduct slowly because I don’t know the tempo”… “I consciously gave you a slower tempo as I don’t know what’s more correct”… “Note that I am conducting faster and slower, faster and slower. Everything is connected to the previous tempo”[21]. In this strange “mosaic” of quotes, Ormandy unconsciously puts the problem of tempo in its pure psychological aspect.

On the other hand, artistic pursuits in the profession of conducting are connected largely to this problem. In this case, it is not just about feeling unsure, complicating the choice of tempo, but more frequently, it is about an aesthetic choice that is directly connected to the issues of artistic thinking.

We see a special interest in tempo and its connection to perception in an interview with Prof. V. Kazandzhiev: “For me, the correct tempo is one that corresponds to the natural pulse of the music, which does not create tension… The musicality has to be normal. Any tension is perceived as nervousness. Gluck and Vivaldi themselves have said that tempo is everything. But when you get up on the conductor’s podium, your pulse increases to 130 beats per minute. You think you’ve hit the right tempo, but it turns out to have been faster under the influence of your own increased pulse… The pulse reflects, above all, on the faster tempos. The more spontaneous a conductor is, the higher the chance for a more spontaneous and correct tempo. There is nothing more annoying than attempts to impose tempos on the artist. Yes, in the common effort of creating, there has to be logic and that comes from the tempos preferred by the conductor as well”[22].

We must note that as a result of everything said so far, that perception of tempo is in direct relation to other cognitive processes such as musical-aural perception, thinking and imagination. It is also highly dependent on the temperament and character of the conductor. But especially strong is the dependency of this perception on the emotional and wilful psychic processes that create one of the most important components of psychological characteristics of the conductor.

In the recent scientific literature focusing on the issues of cognitive psychology, we find conclusions, which to a great extent explain the complexity and compatibility of these processes: “The issue on where to place the boundary between perception and knowledge or even between sense and perception provokes hot debates. Instead, for being more efficient, we have to review these processes as a part of the continuum. Information runs through the system. Different processes address different issues“[23].

In her work “The Musical Audience”, Associate Prof. Irina Haralampieva (PhD), stresses that “[w]e have to note that the musical experience is not only specific but complex. Each moment of perception interweaves senses, emotions, thoughts, memories, associations, etc., which merge into this complex body, spread in the general life experience of the individual and live long after the music has faded away“[24].

C.) Concepts

Concepts characterize a higher level of knowledge and a transition from sensations and perceptions. They represent visual and summarized images of objects and phenomena from the objective world occurring in the brain, which have no impact on senses at a given time. Generally, they are results from processing and summarizing past perceptions[25].

Concepts of different structure and function take part in the creative process of conducting.

Musical-aural concepts are a key component of the creative process of conducting. The main form of expression of these concepts is the internal hearing of the conductor, which Rimsky-Korsakov defines as the “ability for the mental presentation of musical tones and their ratios without the help of an instrument or a voice” [26]. Hermann Scherchen also mentions the significance of internal hearing in his Handbook of Conducting: “The conductor is a presenter of his ideal concepts. The conductor must mentally hear the musical composition in such a clear manner as this music was heard by its creator… This is exactly the perfect internal singing that must create the concept for music in the conductor. If the composition lives in the conductor in its initial form, without being distorted from the material aspect of reproduction, then he/she is worthy of joining the magic of conducting”[27].

Musical-aural concepts appear at the very beginning of the creative process when the conductor reads the musical score. Visual and aural moments are carried out by people with highly developed internal hearing. Then aural perception must immediately provoke corresponding movements and immediately “listen with the eyes”. Robert Schumann says: “Someone said that the good musician, once having heard an orchestra piece as complex as it may be, must see the entire musical score as it is in front of his eyes. This is the highest perfection, which we may imagine”[28].

Upon training the conductor, developing and raising this ability is a paramount task due to the fact that the lack of connection between aural perception and the musical-aural concepts would make it impossible to carry out the creative process. None of the higher mental processes could replace or compensate for such lack of abilities for “hearing’ the musical score.

In addition to the formation of musical – aural concepts, visual perception is the basis for the creation of aural concepts.

In conducting, they are essential in two aspects: first, when conducting without a music score, they may add to the musical-aural concepts preserved in their memory. Depending on the type of memory a conductor has, aural concepts may play a more or less important role.

The second aspect of the appearance of aural concepts in conducting is connected with the use of imagery (visual ideas) created on the basis of the musical content. This process is a result of the connection between different brain centres and the imagination. The occurrence of visual concepts with auditory concepts is an important phenomenon, which is based on the programme music and all genres connected with any form of sound illustration. Rudolf Kan-Schpeier formulates his opinion on this issue as follows: “The fact that the conductor does not usually realize how exactly he/she imagines the content of the composition and how, based on such concept, he/she determines the manner of performance, is also explained with the fact that the essence of such concepts, as a rule, may not be connected with any specific objects… The essence of many compositions, as well as the mental nature of many conductors, is such that the specified concepts of objective nature are not always revealed to them”[29].

The issue for the positive or negative role of the aural – visual associations is too subjective. We cannot and we don’t have to issue “a sentence” – “for” or “against” this phenomenon. The most important thing, in this case, is that it again proves the mutual dependence and the connection between different psychological processes. In particular, we may speak about enriching aural concepts as a result of the complex action of the imagination, the specific – image functions and the emotional sphere, which has an individual and spontaneous nature.

In conclusion, we have to highlight that both visual and musical-aural concepts are in direct correlation with the gained professional experience of the conductor. Prof. Dimitar Hristov writes: “For example, the experienced composer would find the defects of a music sheet even visually, without the help of his/her internal hearing and his/her hand automatically corrects the flow displayed on the music score”[30]. The experienced conductors have the same ability – by gaining knowledge and skills, their musical – aural and visual concepts are enriched, which on its part increases “the palette” of their creative opportunities and the broadness of the mental processes participating in the creative act.

REFERENCES

Berlioz,Hector. Диригентът на оркестъра. ( Chef d’orchestre). In: Изкуството на диригента. (Art of the conductor). Sofia, Music Horisons, 11/ 1979, p.13.

Weingartner, Felix. За дирижирането. (On conducting). In: Изкуството на диригента. (Art of the conductor). Sofia, Music Horisons, 11/ 1979, p. 85.

Kan-Speyer, Rudolf. Handbook in conducting. In: Дирижерское Исполнительство. (Conducting performing art). Moskow: Music Publishing House,1975, p.247.

Karapetrov, Konstantin. Interview with prof. Vassil Kazandzhiev. In: Музика, вчера, днес. (Music, yesterday, today) – 6/1994, p.5-6.

Maazel, Lorin. Интервю. (Interview) – IN: Списание ЛИК, LIK 41/1983.

Matheopoulos, Elena. Караян – живот, изкуство, работа. (Karajan – life,art,work.) In: Българска музика,( Bulgarian Music) , 2/1988, p.20.

Ormandi, Eugene. Куриозите на репетиционната работа. (Curiosity of rehearsal’s work). In: Музика, вчера, днес (Music, yesterday,today), 1/1999.

Piryov, Gencho, Ljuben Desev. Кратък речник по психология. (Short Dictionary in Psychology). Sofia: Partizdat, 1981.

Sivizianov, Andrey. Проблема мышечной свободы дирижера хора, (Problem about the choral conductor’s muscle’s freedom). Moskow: Music Publ. house,1982.

Stanislavskii, Konstantin. Работата на актьора над себе си. (Actor’s work). Sofia: East-West PH, 2015. ISBN: 978-619-152-690-1.

Sternberg,Robert.J.Когнитивнапсихология. (Cognitive Psychology). Sofia: East-West PH, 2012. ISBN 978-619-152-014-5.

Teplov, Boris. Психология музыкальных способностей. (Psychology of Music Abilities). Moskow: Academy of Pedagodical Sciences PH, 1947.

Haralampieva, Irina. Музикалната публика.(Music Audience). Sofia: Haini,2014. ISBN 978-

619-7029-20-8.

Hristov, Dimitar. Хипотеза за полифоничнияс троеж. (Hypothesis on polyphonic building).Sofia: Science and Art,1994.

Hristozov, Hristo. Музикална психология. (Music Psychology). Plovdiv: Makros,1995.

Scherchen, Hermann. Учебник дирижирования. (Handbook of conducting). In: Дирижерское исполнительство (Conducting performing art). Moskow: Music PH, Москва: 1975.

Strauss, Richard. Десять золотых правил (Ten golden rules) .In: Дирижерское исполнительство Conducting performing Art).Moskow: Music PH, 1975.

Schumann, Robert. Quotation in Music Psychology by Hristo Hristozov. Plovdiv: Makros,1994.

Theodora Pavlovitch is Professor of Choral Conducting and Head of the Conducting Department at the Bulgarian National Academy of Music. She is also Conductor of the Vassil Arnaoudov Sofia Chamber Choir and the Classic FM Radio Choir (Bulgaria). In 2007/2008 she conducted the World Youth Choir and was honoured by UNESCO with the title Artist for Peace, due to the WYC’s success as a platform for intercultural dialogue through music. Prof. Theodora Pavlovitch is frequently invited as a member of Jury panels to a number of international choral competitions, as conductor and lecturer to prestigious international events in 25 European countries as well as the USA, Japan, Russia, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Israel. Since 2012, T. Pavlovitch has been a representative for Bulgaria in the World Choral Council. Email: theodora@techno-link.com

Theodora Pavlovitch is Professor of Choral Conducting and Head of the Conducting Department at the Bulgarian National Academy of Music. She is also Conductor of the Vassil Arnaoudov Sofia Chamber Choir and the Classic FM Radio Choir (Bulgaria). In 2007/2008 she conducted the World Youth Choir and was honoured by UNESCO with the title Artist for Peace, due to the WYC’s success as a platform for intercultural dialogue through music. Prof. Theodora Pavlovitch is frequently invited as a member of Jury panels to a number of international choral competitions, as conductor and lecturer to prestigious international events in 25 European countries as well as the USA, Japan, Russia, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea and Israel. Since 2012, T. Pavlovitch has been a representative for Bulgaria in the World Choral Council. Email: theodora@techno-link.com

Edited by Shanae Ennis-Melhado, UK

[1]Piryov, Gencho. Lyuben Desev. Concise Dictionary in Psychology Sofia: Partizdat, 1981, page 167-168.

[2]Piryov, Gencho. LyubenDesev. Concise Dictionary in Psychology Sofia: Partizdat, 1981, page 259.

[3]Mateopulous, Elena. Karajan – life, art, work. – В: Bulgarian Music, No. 2/1988, page 17.

[4] As above, page 20.

[5] Maazel, Lorin. Interview in LIK Magazine, No 41/1983.

[6]Scherchen, Hermann. Handbook of conducting. – В: Conducting performing act. Moscow: Publ. Muzika, 1975, page 222.

[7]Stanislavskiy, Konstantin – The actor’s proper care of himself. Sofia: East-West, ISBN; 978-619-152-690-1, с. 180.

[8]Hristozov, Hristo. Musical psychology. Plovdiv. Macros, 199

[9] The same, page 40-46.

[10] As above, page 41.

[11]Strauss, Richard Ten Golden Rules for the Album of a Young Conductor – В: Conducting performing act. Moscow: Muzika, 1975, page 397.“

[12]Teplov, Boris. Psychology of Music Abilities. Moscow: Academy of Psychological Sciences, 1947, page 68.“

[13]Hristozov, Hristo. Musical psychology. Plovdiv. Macros, 1995, page 11

[14]Piryov, Gencho, Lyuben Desev. Concise Dictionary in Psychology Sofia: Partizdat, 1981, page 36.

[15]Teplov, Boris. Psychology of Music Abilities. Moscow: Publ. Academy of pedagogical sciences, 1947, p. 59.

[16]Hristozov, Hristo. Musical psychology. Plovdiv. Macros, 1995, page 76

[17] As above, page 69.

[18]Weingartner, Felix. On conducting. – В: Art of conducting. Sofia: Musical horizons, issue 11/1979, p. 85.

[19]Piryov, Gencho. LyubenDesev. Concise Dictionary in Psychology Sofia: Partizdat, 1981, page 37.

[20]Berlioz, Hector. Orchestra conductor – in: Art of conducting. Sofia: Musical horizons, issue 11/1979, p. 13.

[21]Ormandy, Eugene. Curiosities of rehearsal work. In: Music, yesterday, today. issue 1/1999, p. 52, 54, 60.

[22]Karapetrov, Konstantin. Interview with prof. Vasil Kazandzhiev. – In: Music, yesterday, today. issue 6/1994, p. 5-6.

[23] Sternberg, Robert. Cognitive Psychology Sofia: Iztok-Zapad, 2012, page106.

[24]Haralampieva, Irina. The Musical Audience Sofia: Haini, 2014, page 63

[25]Piryov, Gencho. LyubenDesev. Concise Dictionary in Psychology Sofia: Partizdat, 1981, page 150-151.

[26]Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay. Quote by Hristozov, Hristo. Musical psychology. Plovdiv. Macros, 1995, page 84

[27]Scherchen, Hermann. Handbook of conducting. – В: Conducting performing act. Moscow: Muzika, 1975, page 209-210.“

[28]Schumann, Robert Quote by Hristozov, Hristo. Musical psychology, page 86

[29] Kan-Schpeier, Rudolf. Handbook on Conducting – In: Conducting performing act. Moscow: Muzika, 1975, page 209.

[30] Hristov, Dimitar. Hypothesis for the polyphonic structure. Sofia: Naukaiizkustvo, page 133

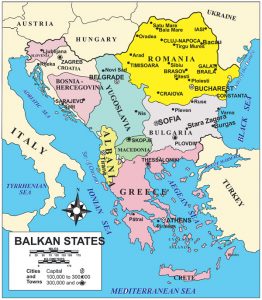

All these meters exist in different combinations of the metric groups and they are usually combined with corresponding dances. Therefore, most of the meters have been named upon the dances called “horo” in Bulgaria, “kolo” in Serbia and Croatia, “χορός” (horos) in Greece, and “oro” in Macedonia – collective dances deeply grounded on the meters specific for the region.

All these meters exist in different combinations of the metric groups and they are usually combined with corresponding dances. Therefore, most of the meters have been named upon the dances called “horo” in Bulgaria, “kolo” in Serbia and Croatia, “χορός” (horos) in Greece, and “oro” in Macedonia – collective dances deeply grounded on the meters specific for the region. 11/8 (2+2+3+2+2), (2+2+2+2+3) , (3+2+2+2+2) – called Kopanitsa.

11/8 (2+2+3+2+2), (2+2+2+2+3) , (3+2+2+2+2) – called Kopanitsa. damage was caused to national cultures in the 500 years that followed. One of the most important factors that preserved national spirit over the ages of domination was music – rich folk traditions and the old orthodox chants sang in monasteries and nunneries. Unfortunately, as a result of the frequent robberies and fires, most of the rich cultural heritage hidden in them was destroyed. But because of the specific historical conditions, the influence between orthodox and folk songs was very intensive and a great number of anonymous orthodox chants with folk elements can be found in the liturgy even today.

damage was caused to national cultures in the 500 years that followed. One of the most important factors that preserved national spirit over the ages of domination was music – rich folk traditions and the old orthodox chants sang in monasteries and nunneries. Unfortunately, as a result of the frequent robberies and fires, most of the rich cultural heritage hidden in them was destroyed. But because of the specific historical conditions, the influence between orthodox and folk songs was very intensive and a great number of anonymous orthodox chants with folk elements can be found in the liturgy even today.