Conducting Hope: the only men's prison choir in the U.S. to perform outside prison walls

By Tobin Sparfeld, choral conductor and teacher

Inside a nondescript room in Lansing, Kansas, that functions as the facility’s chapel, a handful of men sit in old church pews, music in hand. Standing before them, a middle-aged man in a goatee signals for the warm-up pitch played by the accompanist on the electric keyboard. The choir has begun rehearsing. While many choir rehearsals in the world begin like this, this one has a notable difference. The facility is a prison, the Lansing Correctional Facility, and the singers are its prisoners.

So begins Conducting Hope, a documentary chronicling the East Hills Singers, founded in 1995 by Elvera Voth, a choral conductor who retired to Kansas from her previous home in Alaska. Voth also helped form the Kansas City-based non-profit organization Arts in Prison with the goal of promoting “responsibility, accountability, and leadership.” The East Hills Singers are now directed by Kirk Carson, a former opera singer who also works as a defense information technology contractor. Carson has directed the singers for over four years, and has been profoundly changed by his experiences with the East Hill Singers. “I started out doing this with the thought that I should be giving something back,” he says. “That became a silly concept within a couple of weeks because I have gotten so much more back than I will ever be able to give.”

Writer Leslie Cockburn says the most difficult thing to do when making a documentary is to make something complex appear simple. In Conducting Hope, the complexity lies in making a cohesive ensemble. The inmates are not auditioned, and the membership often fluctuates. Most of the roughly fifty singers have not sung in an ensemble before, and during the concerts they perform with a separate men’s community choir, singing together for the first time that very day. They are the only men’s prison inmates in the USA to perform outside prison walls.

The complexity of the inmates’ lives is also enormous. The singers have been incarcerated for numerous crimes, including drug use and manufacturing, robbery, attempted murder, and sexual offenses. Many come from difficult circumstances and do not take well to criticism. For some, this is their first group activity. Despite their various ages and backgrounds, the singers have one thing in common—they are all scheduled to be released back into society. The skills they learn here are meant to improve their lives and help them succeed when they are released.

The story of Conducting Hope is that of redemption. During the film we see men along various stages of that journey. We see rapper Essex Sims, an inmate unable to join the choir due to being given a life sentence, who has composed a song combining his rap lyrics and Gregorian chant melody. There is Kurt Irish, an inmate dealing with alcohol and drug addiction, and how to deal with withdrawal symptoms was excited to perform his final concert before his release. There are also those on the other side of the redemption saga. David Jones, who had previously sung as an inmate and continues now as a community singer after his release (or, as the East Hill singers refer to it, his “graduation”), runs his own contracting business.

We also see family members and other relatives of the inmates who have all been deeply affected by prison sentences. Some relatives are unable or unwilling to visit the singers in prison, so the four yearly concerts allow the inmates to reconnect with family and allow them to be seen in a positive light, if only for a fleeting moment.

What is most remarkable about the East Hill Singers is how average everything is.

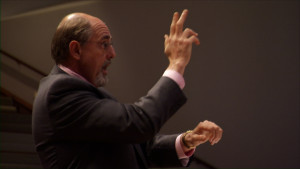

The inmates do not make up a very strong choir. Intonation is an issue, voices stick out, and their musicianship ebbs and wanes during rehearsal much like their focus. The community choir that rehearses separately sounds somewhat better but not much. The ensemble’s most difficult selection is the first movement of Randall Thompson’s Testament of Freedom. Carson says that sometimes “the level is not what I would like to have, but I have to remind myself that the level of the performance is not the underlying reason for being here.” Carson himself is average, with a conducting gesture that while clear, is plodding, deliberate, with his arms suspended above his chest and his eyes riveted down at the score.

But what Conducting Hope shows its viewers is the transforming power of music, even in average choirs. As the first scenes of the film take place within the prison walls, we soon get to experience life outside the facility through the eyes of the prisoners themselves. They find immense pleasure in the simplest of activities, including their van ride to the church concert hall. Their eyes light up as they eat a regular meal at the church, tasting “real food.” And their reactions after the concerts show how much they value the normalcy of these moments.

Conductors understand the challenges Carson faces. With sometimes as many as fifty amateur and beginner singers, his words of advice are those we all know. “Articulate, articulate, articulate.” “Folders in your right hand—your other right.” The scene recounting the setup of risers and other various last-minute concert logistics is very familiar. But his worldly, pragmatic approach is helping to transform his singers’ lives. He features numerous soloists in his performances who gain confidence through their experience. And in between each song on the program is a lengthy introduction, each one spoken by a different inmate. While it may seem mundane, Carson spends a lot of time working with the inmates in preparation for their public speaking before their audiences. “I know for a fact that if they can get up in front of two hundred people and give a two minute narration, when they get out of prison they can go and do a job interview. That’ll be easy.”

Produced and directed by Margie Friedman, this is a documentary the general public can enjoy, but conductors will value it for a special reason. We know that even ordinary, mundane musical experiences have the power to heal mankind. Yet in this film, against the backdrop of lives marred by horrific actions, we see that transformation begin to take hold: singers learning about leadership, teamwork, and personal responsibility. They share their pain, hopes, and values openly. They learn the value of delayed gratification, learn about “grit,” learn about how to think critically and use criticism to improve one’s skills. The concerts are some of the best models of this for the singers. As many inmates have been told countless times of their numerous failures, many see choir membership simply as an opportunity to do something they have not yet failed at. And while they struggle, they do not fail. As the audience members react to the concert, their most common reaction is that the singers “don’t look like prisoners.” And, for a few hours, they are not. As one inmate’s mother says, “When I look at the choir, I don’t just see my son, but honestly, I see a lot of mother’s sons up there. Maybe one of the other guys doesn’t have his mother there, so it makes me feel really good to be part of this.”

As dedicated musicians, we want to know how music can touch more people’s lives and enrich our communities. The East Hill Singers are a success story. The U.S. recidivism rate in prisons is 50%. In East Hill Choir, it is 18%. While happy endings are not universal, Conducting Hope is a testament to the power of music. It shows choral conductors we can develop and expand exciting choral music programs to reach more people and further our purpose.

Edited by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy-UK