The Development of Choral Singing in Malta: A Historical Overview

By Joseph Vella Bondin, musicologist and singer

Up to the end of World War II (1939-45), Malta’s traditional preoccupation in music was essentially limited to two forms – Roman Catholic sacred music, primarily liturgical, and Italian opera, mainly performed in the exquisite baroque Manoel Theatre constructed ad honestam populi oblectationem[1] in 1731 and, subsequently, in the magnificently proportioned Royal Opera House, built on a design by Edward Middleton Barry[2], which opened its door on October 9, 1866, with Bellini’s I Puritani. Luftwaffe bombers devastated this theatre on April 7, 1942, and it was not rebuilt, opera moving back to the still-standing Manoel Theatre.

That Maltese ‘art’ music was moulded on Italian models is consequently a historical fact that needs no amplification. That the Maltese musical heritage was dominated by sacred, mainly liturgical, compositions is now another established fact. This statement might, in the past, have occasioned some comments, given the well-known and traditionally deeply-rooted Maltese infatuation with opera to the virtual total exclusion of other forms of theatrical spectacle at least up to the end of World War II. But even when there was no longer any valid reason why this aspect of Maltese cultural totality should have remained Italy-oriented, complex political, social and economic reasons continued to ensure that the nation’s operatic gravitation remained firmly Italian to the almost total exclusion of non-Italian opera, including Maltese composed works that, a priori, should have earned the automatic backing of Maltese society[3]. Given this, Maltese composers, the best of them having remunerative appointments as church musicians, concentrated on composing sacred music for which they had a tangible market and considered, probably very unwillingly, opera-writing as a mere side-line.

If we wish to talk about an indigenous choral tradition both from the point of view of performance and also of composition, we have to seek it then primarily in church music as an integral part of the Roman Catholic liturgy and, to a lesser extent, in the operatic theatre. Choirs, in the sense of large groups of a secular independent provenance as seen in other Western nations, did not exist.

Given Malta’s extended history of continuous colonization which began in the ninth century B.C., it may be a cliché to state that up to the middle of the twentieth century the events which fundamentally affected Maltese political, social and cultural history were externally determined. The situation was largely accepted by the native population and it might even have had the advantage of shielding Malta, a minuscule archipelago state of 320 square kilometers strategically situated in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea with a current population of 400.000, from the direct vacillations of external realities. The after-effects of World War II, reinforced by the granting in 1964 of political independence from Great Britain, the then colonizing power, produced the uncharted reality of a new national identity in a global situation that was rapidly changing, a state of affairs which initiated a period of self-questioning not only for the Maltese intelligentsia but also for most strata of the population.

It became evident that composing music for the liturgy was not of great concern in the post-Independence environment. First of all, certain ecclesiastical developments during the twentieth century starting with Pope Pius X’s Motu proprio (1903) on church music and culminating in the faithful-orientated promulgations of Vatican Council II (1962-5), had reduced considerably the activities of the traditional Maltese cappella di musica and, as a direct corollary, the importance of and the need to compose new liturgical works. But even if these developments had not occurred, it is still doubtful whether sacred music would have appealed to the post-Independence composer in an environment which was becoming rapidly secularized.

Liturgical works form a small part of the oeuvre of Carmelo Pace, Charles Camilleri, and Joseph Vella, the three most frequently performed post-Second World War composers. They were also very influential through their teaching and, for the first time in the history of music in Malta, started setting texts in Maltese.

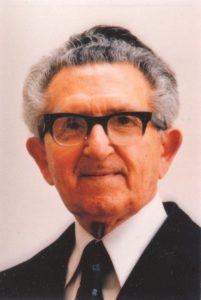

Carmelo Pace (1906-1993) wanted to compose operas which focused on Maltese history. He wrote four – Caterina Desguanez (1965) based on the Great Siege of 1565, I Martiri (1967) narrating the tribulations of the Maltese during the brief French occupation, Angelica (1973) telling the story of the Bride of Mosta, and Ipogeana (1976) with a plot highlighting the Maltese Neolithic era. But he still bowed down to established norms by composing them to libretti in Italian and on Italian methods. Additionally, he composed many secular and sacred large-scale chorus-oriented works.

Carmelo Pace (1906-1993) wanted to compose operas which focused on Maltese history. He wrote four – Caterina Desguanez (1965) based on the Great Siege of 1565, I Martiri (1967) narrating the tribulations of the Maltese during the brief French occupation, Angelica (1973) telling the story of the Bride of Mosta, and Ipogeana (1976) with a plot highlighting the Maltese Neolithic era. But he still bowed down to established norms by composing them to libretti in Italian and on Italian methods. Additionally, he composed many secular and sacred large-scale chorus-oriented works.

Charles Camilleri (1931-2009) challenged all traditional canons by composing his first two full operas, Il-Weghda (1984) and Il-Fidwa tal-Bdiewa (1985), not only to Maltese texts but also to harmony and melodic lines springing directly from Maltese traditional music. He used the same formula for his oratorio Pawlu ta’ Malta (1985) and the cantata L-Ghanja ta’ Malta (1989). In the new political ambience, these works gained wide national consensus, a newborn awareness of and a burgeoning pride in an inherent musical identity. In 1992, he was appointed first Professor of Music at the University of Malta, a position he held till 1996. This gave him the opportunity to propagate his intuitions about the importance of Maltese folk music and soundscape as the catalyst for the production of a distinctive Maltese sound to create a representative Maltese school of composition. His example and teaching influenced radically a new crop of composers. Like Pace, Camilleri and these emerging composers have contributed interesting and diverse works for choir or containing important choral movements.

Charles Camilleri (1931-2009) challenged all traditional canons by composing his first two full operas, Il-Weghda (1984) and Il-Fidwa tal-Bdiewa (1985), not only to Maltese texts but also to harmony and melodic lines springing directly from Maltese traditional music. He used the same formula for his oratorio Pawlu ta’ Malta (1985) and the cantata L-Ghanja ta’ Malta (1989). In the new political ambience, these works gained wide national consensus, a newborn awareness of and a burgeoning pride in an inherent musical identity. In 1992, he was appointed first Professor of Music at the University of Malta, a position he held till 1996. This gave him the opportunity to propagate his intuitions about the importance of Maltese folk music and soundscape as the catalyst for the production of a distinctive Maltese sound to create a representative Maltese school of composition. His example and teaching influenced radically a new crop of composers. Like Pace, Camilleri and these emerging composers have contributed interesting and diverse works for choir or containing important choral movements.

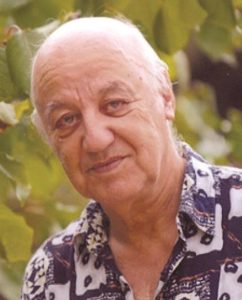

Joseph Vella (b. 1942) is Associate Professor of Music at the University of Malta and a gifted conductor. A composer with a self-confessed allegiance to contrapuntal music, his works are all ingrained in a personal idiom that stems mainly from a neo-classicist indication. His impressive oeuvre, in various forms and designs, includes many outstanding works for choir and, moreover, his deep interest in old Maltese music, particularly of the Baroque era that he continues to edit and revive in concert form, has been instrumental in enabling the Maltese nation to discover an impressive musical past which include Neapolitan masses and psalms for two choirs.

Joseph Vella (b. 1942) is Associate Professor of Music at the University of Malta and a gifted conductor. A composer with a self-confessed allegiance to contrapuntal music, his works are all ingrained in a personal idiom that stems mainly from a neo-classicist indication. His impressive oeuvre, in various forms and designs, includes many outstanding works for choir and, moreover, his deep interest in old Maltese music, particularly of the Baroque era that he continues to edit and revive in concert form, has been instrumental in enabling the Maltese nation to discover an impressive musical past which include Neapolitan masses and psalms for two choirs.

These innovative musical developments in post-World War II aspiration and sensitivity were combined with the setting up, often privately instigated, of the musical environment and structures needed to present works in a non-operatic or non-liturgical ambience. They included newly-built theatres and concert halls, among them the auditorium of the Catholic Institute (1960) in Floriana. Very important was ecclesiastical acceptance that Maltese churches, many spectacularly structured and acoustically valid, were a legitimate site for the hosting of suitable musical productions.

The new structures also included the formation of independent amateur choirs, mostly for mixed voices and most of them founded by members of the clergy, not really surprising given that the Maltese population was, at that time, decidedly conservative and as a rule frowned upon the general mixing of sexes without proper supervision. The first, the Hamrun Choir, was set up in 1949 by the priest-musician Fr Joseph Cachia (1922-2001), its director and choirmaster. Others included the Cantate Domino Choir of Zurrieq instituted by Fr Mikiel D’Amato (1926-2002) in 1956; the St Julian’s Choir founded a year later by Mgr Guido Calleja; the Jesus of Nazareth Choir created in 1960 by the Dominican monk Salv Galea; and the St Monica Choir which the Augustinian nun, Sr Benjamina Portelli, started in Mosta in 1964. It can be stated that these choirs, and others, had a parochial origin and purpose but over time won a national endorsement.

To achieve the normal objective for which it is formed, a choir has to perform in public. The problem was that there was no tradition of suitable openings outside liturgical rites. Clearly choirs had to take the initiative to inform and show the public the new musical scenarios they were now making possible. It was the Hamrun Choir which took the initiative. In the then absence of apposite Maltese material[4], it embarked on the annual preparation and presentation of sacred oratorios from the international repertory. The first two were Handel’s Messiah on January 3, 1959, and Mendelssohn’s St. Paul on April 29, 1960, chosen to commemorate the nineteenth centenary of the Apostle Paul’s shipwreck in Malta in A.D. 60, followed by Judas Maccabaeus and Elijah. Never before had such outstanding works been performed in Malta and the fact that they were performed by an all-Maltese cast increased their impact. Other choirs soon followed the lead.

More secular in character were a number of excellent choral groups which also emerged. The Malta Choral Society started in 1953. Its members were British residents and visitors but with an ever increasing number of Maltese singers. Works performed included Messiah, The Creation, Faure’s Requiem, Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia, Carmina Burana and a concert version of Verdi’s Nabucco. Organisational difficulties led to its dissolution in the early 1980s. The Gruppo Corale Primavera, founded and directed by Joe Fenech and active between 1959 and 1970, produced several cultural and variety shows.

The Malta Operatic Choral Society was set up in 1953 by music organiser and tenor Joe Lopez with the principal aim of offering services to opera impresarios. An all-male choir of about 20 members, it was directed by composer and conductor Joseph Abela Scolaro. Its most innovative undertaking was its participation in the 1959 Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod held in North Wales from July 7 to 12, the first Maltese choir to enter the international arena. The result obtained was rather mediocre as it finished only 14th from among the 19 choirs that competed in the Male Choirs division. However the experience gained was considered important not only for the choir itself but also for the nation as a whole since it offered an effective means for assessing the technical and vocal worth the emergent choir movement of a small insular nation was achieving.

The most tangible and immediate result was the development of the Malta Operatic Choral Society into a mixed national choir of 60 members, accepted only after a strict audition or, in respect of trained active singers, by invitation. The choir mistress was pianist Bice Bisazza (1909-1994) and the director was conductor and composer Joseph Sammut (b. 1926). As expected, it developed into one of the best choirs ever established in Malta. Its first engagement and defining challenge was participation in the 1960 Eisteddfod held from July 5 to 10. The competitive results obtained were good but the landmark achievement occurred during the Saturday Evening Concert. Before an audience of about 10,000, its interpretation of L-Imnarja, a choral song for unaccompanied mixed voices based on Maltese folk rhythms composed for it by Carmelo Pace, was so striking and the applause was so immense and insistent that it had to be encored, even though it was against the Festival rules for encores to be given, a feat even reported in the British media.

The final stage in the choir’s development was a change in its name to Chorus Melitensis. Of the many admirable concerts it gave, its most prominent presentation, at least historically, was Verdi’s Requiem in April, 1966, the first time that this universal masterpiece was presented live in Malta. The performance was a joint venture with the Malta Choral Society to form a combined choir of over 120 singers. Unfortunately, organizational difficulties led to the disbanding of the Chorus in 1979.

However by that time, the choir movement had put down deep roots, further nurtured by the in-depth spread of music education, the persuasive foreign example through international media entertainment, and the expanding national interest in forms traditionally ignored[5]. Now groups started to be formed all over the country, trained and conducted by emerging musicians whose training was technically sound and multifaceted. The improved choral environment encouraged the writing of apposite works by established and up-and-coming composers particularly to texts in the indigenous language, now the dominant language for vocal compositions.

Perhaps the most visible sign of this new national awareness was the setting up, under government auspices, of the Malta International Choir Festival in 1989, with Charles Camilleri as its artistic director. In 1998 this responsibility was passed on to Rev. John Galea, a composer with a vast experience in choral direction and management. Between 1989 and 2004 the festival was held yearly in early November and a substantial number of choirs from different countries, including Malta, participated.

A major change was then introduced. After discussions with Interkultur, the government decided that collaboration with this worldwide institution would enhance the Malta Festival. It was now agreed to organize it biannually, under the guidelines and criteria of the Musica Mundi label. The first iteration, called ‘The Malta International Choir Competition and Festival’ was held in 2006, and it attracted 22 choirs from fifteen different countries. Others, all equally successful, were held in 2007, 2009 and 2011.

[1] Inscription above the main entrance to the theatre.

[2] The architect of London’s Covent Garden.

[3] Of the 161 different operas presented at Malta’s Royal Opera House between its inauguration on October 9, 1866 and its destruction on April 7, 1942, a period of just over 75 years, 113 (or over 70%) were by Italian composers, 8 by Maltese and 40 by non-Italians. Most of the non-Italian works were heard in Malta only after Giovanna Lucca, wife of the founder of the publishing house of Lucca, in an attempt to find an alternative to Verdi whose extremely popular operas were being published by the rival firm of Ricordi, zealously introduced into Italy the works of foreign composers. They were performed in Malta in the Italian-translated text heard in Italy.

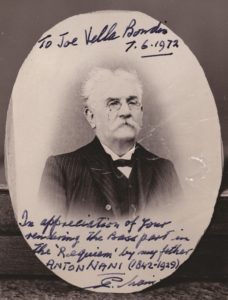

[4] The only valid exceptions were two oratorios, the secular La lampada (1901), composed by Luigi Vella (1868-1950), and San Paolo evangelizza i Maltesi (1913), by Carlo Diacono (1876-1942), with text in Latin by Giovanni Formosa, written to commemorate the 1913 International Eucharistic Congress held in Malta.

[5] Thus, as part of its corporate responsibility, APS Bank promotes Malta’s musical heritage through the organisation of annual flagship concerts, the first being A Concert of Baroque Sacred Music by Maltese Composers presented on November 10, 2001. The selected music is also recorded on compact disc. In 2007, the Bank decided to extend its commitment by initiatives which support the composition of new works. So far two National Competitions (2007, 2012) have been organised. The participation of choirs in these initiatives is underlined. Cf. the Bank’s official website: www.apsbank.com.mt

Edited by Mirella Biagi, Italy / UK