Choral Music Changing Young Lives in Australia

Gondwana National Indigenous Children’s Choir

By Lyn Williams, Artistic Director & Founder Gondwana Choirs

As conductors we are driven by passion, driven by inspiration and driven by a desire to achieve the highest possible artistic standards. As choral conductors we also have the privilege of being involved in the most inclusive form of music making. A choir only comes to life when every voice, every personality is captured and expressed through the performance. As a conductor of children’s choirs I have also found it thrilling to see young people mature and thrive in the choral environment and go on to become fine professionals in music and in other spheres as they maintain the same passion and drive in life as they did in their choral music singing.

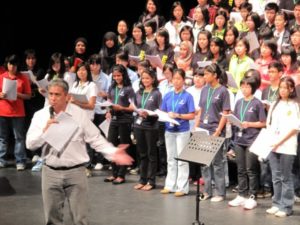

The organization, which I founded in 1989, began with the Sydney Children’s Choir and still trains over 400 children each year in a comprehensive choral and music program based in Sydney. In 1997 our National Gondwana Choirs program began with Gondwana Voices – a truly national children’s choir whose singers come from every corner of Australia. Our annual Gondwana National Choral School now involves over 300 of the country’s most talented young singers, conductors, and now choral composers, who come together in a summer camp, then perform concerts and undertake national and international tours throughout the year. The many Gondwana Choirs perform at a high level, often collaborating with our finest composers and instrumental ensembles such as the Sydney Symphony, Synergy Percussion Ensemble and the Australian Chamber Orchestra. The Gondwana National Indigenous Children’s Choir is the newest group in our choral family.

Until the last couple of years, my primary motivator as a choral conductor was to see young people performing at the highest possible artistic standards. This was always coupled with a strong urge to discover, commission and create new works, collaborations and performances through which the powerful voices of young people could be heard.

Although my motivation to reach artistic peaks still remains very strong, more recently I have found enormous satisfaction in creating musical and social opportunities for young talented people who would never otherwise have access to our extensive and national Gondwana Choirs programs.

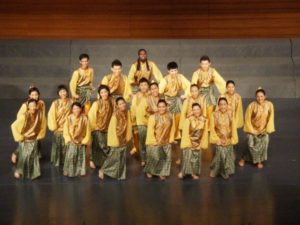

The Gondwana National Indigenous Children’s Choir (GNICC) grew out of a remarkable collaboration between our Sydney Children’s Choir and communities in the Torres Strait Islands (one of the most remote and beautiful areas of Australia – which lies between the northern mainland of Australia and Papua New Guinea) in 2008 and 2009. This collaboration involved children from both communities visiting each other in their home towns, in Sydney and in the Torres Strait, and the result of working together was a highly successful children’s opera called Ngailu, Boy of the Stars, created primarily by the Torres Strait Islander choreographer/director, Sani Townson and the young Australian composer, Dan Walker.

It became clear to me through this collaboration that there was a wealth and depth of un-nurtured talent within Australia’s Indigenous communities and it became apparent to me that this was the missing link in our Gondwana programs. Many of Australia’s Indigenous people suffer from significant social disadvantage. The levels of health and education in Australia’s Indigenous population are significantly lower than other sectors of Australia’s population, and sadly, they are also over-represented in Australia’s judicial system. Yet young Indigenous people are justifiably proud of their rich and diverse culture. The sporting talents of young Indigenous Australians have long been recognized while others yearn for an opportunity to represent their culture and the hopes and dreams of their generation through their song.

Initially, to get the Choir underway, we undertook lengthy discussions with Indigenous leaders and with Indigenous artists, and a plan slowly emerged. I began a series of workshops in urban, regional and remote regions of Australia, making contacts with schools and Indigenous communities – seeking out young talented singers and working closely with local leaders to develop local support for the project. The interest in this program was overwhelming.

In a project which is as much social as musical, the GNICC is aiming to give many talented Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children opportunities to develop their confidence, broaden their life experiences, and therefore expand their horizons and potential, through choral singing. To this end we have developed a three-tiered structure which begins at the grass roots level where I work with children in schools and Indigenous communities, identifying the children who show an aptitude and enthusiasm for singing. One week I might be working at inner city schools in Sydney and the next you might find me driving through crocodile infested waters in remote Northern Territory to work with children who have never travelled out of their isolated communities.

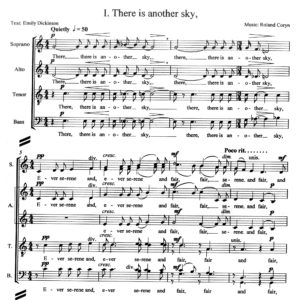

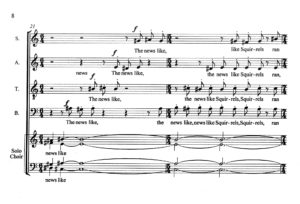

Once selected, we gather all the children from a region together at a Regional Music Camp to work with other conductors, composers and other creative Indigenous artists. This is where the real work begins. Children begin to learn about choral singing, basic notation, performance and personal skills such as commitment and focus. One really important aspect which is always stressed in these camps is creative activity and composition. The children are always active participants in the creation of new works which then become part of their repertoire. Very often these songs are in their local language. Many Australian Indigenous languages are rapidly disappearing and the children themselves feel strongly that their songs will go some way to preserving their unique languages.

From these Regional Music Camps, children are selected to become part of the Gondwana National Indigenous Children’s Choir who meet nationally to work on specific projects and activities. Since the Choir’s founding, children of the GNICC have had the opportunity to travel and perform in the Sydney Opera House, in a major television advertising campaign at the Shanghai World Expo in China, and in the United States.

Though choral developments can be generally very slow, there are occasions when, in a blink of an eye, a life can be changed and for that person, there is no turning back.

Last February, I travelled again to the Torres Strait Islands. In a small school on Thursday Island I was presenting a choral workshop in which there was a shy little nine year old boy. It was clear from the outset that Richard (not his real name) loved to sing. His voice rang out clear and loud above the voices of many of the other children. Feeling the workshop going well, I asked Richard to sing a passage for the class on his own. I felt the whole class flinch yet Richard sang out confidently and proudly. I later found out from teachers that Richard had barely ever spoken to anyone, including the members of his large family, he never read out loud, and he never answered questions in class. Richard’s life changed that day when he discovered that he had a voice and could sing like an angel.

Now as a member of the Gondwana National Indigenous Children’s Choir, Richard has participated in a Torres Strait Regional Music Camp and more recently has been down to Sydney for the very first time to perform as part of a larger choir for Oprah Winfrey’s Australian television programs from the steps of the Sydney Opera House. Although he is clearly still a shy little boy, Richard now speaks enthusiastically about his love of singing and his positive experiences with the Indigenous Children’s Choir. Richard’s world is now one of boundless possibilities. Although the effect of a choral program is rarely so rapid and significant, the GNICC is already having a profound impact on the lives of many Indigenous children in Australia.

The GNICC now forms an important part of the family of Gondwana Choirs. Its members are passionate young Australians who deeply touch audiences whenever they perform. But, the GNICC still faces many challenges. Australia is a vast country and children in remote areas really suffer from the physical, mental and educative tyranny of such distances. Foremost amongst these challenges is Gondwana Choirs’ capacity to be able to provide regular on-going training to choristers in remote areas, so that they can continue developing their singing, reading and writing skills – allowing them over time to realize their full potential. So, Gondwana Choirs is in the early stages of establishing an internet network linking more skilled young singers in urban areas with children in remote areas to assist and support the developmental process.

Whether or not these young Indigenous singers choose to become musicians in the future, involvement in their choir will provide the singers with extraordinary opportunities. Already we know that GNICC singers will increase their attendance at school, they will learn an ongoing sense of commitment which leads to greater excellence and the rewards of personal pride and achievement, they will see a bigger Australia and a bigger world, they will befriend hundreds of other like-minded motivated young people, and they will have a voice to express the dreams of their people – now and into the future.

Edited by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy