Duruflé and his sacred choral music, Requiem Op. 9

By Francesco Barbuto, choral conductor and composer

The Requiem (Mass for the dead) has been one of the most important parts of the Catholic liturgy since the 11th Century.

In the Requiem mass, some parts of the Ordinarium (Gloria and Credo) are taken out and other specific parts such as the Introit (Introduction), Dies Irae (Day of Wrath), Lux Aeterna (Eternal Light), Libera me, Domine (Deliver me, Lord) are added.

The word Requiem comes from the recitation of the first prayer in the Introit: “Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine” (Eternal rest grant unto them, Lord).

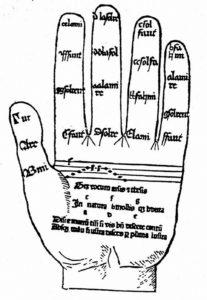

Throughout history, many composers have tried their hand at writing a Requiem based on, as a thematic source, the original Gregorian melodies; among these are Dufay, Ockeghem, La Rue, Vittoria, Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi, Liszt, Brahms, Britten, Ligheti. Duruflé himself harks back “faithfully” to Gregorian chant in the VI mode, the Hypolydian, used by the Benedictine monks of Solesmes:

In the footsteps of the musical compositional style of Gabriel Fauré, who broke with the tradition of writing a Requiem with a sweeping “dramatic” character:

He composed his Requiem in D minor, Op. 48 between 1870 and 1890, and offers a comforting view of death, as if wanting to convey a journey towards to a place of peace and rest, rather then to somewhere horrifying. Responding to critics, Fauré replied: “It has been said that my Requiem has failed to convey a sense of the terror of death… but this is how I imagine it: more a surrender filled with peace and a wish for happiness in the afterlife”.

Duruflé too, in true homage to the great Master, follows this aesthetic, which will formalise a new, typically French, tradition. It is not coincidental that neither will set to music the Dies Irae, the movement usually considered to be the most ‘dramatic’ of the texts and passages of the Mass for the dead.

His Requiem, Op. 9 (dedicated to the memory of his father), in three versions: for choir, organ and orchestra, choir and organ, choir and string quintet and organ (with the option of trumpets, harp and timpani), is by far the longest and most complex work he composed during his professional musical life. It appears that Duruflé was already working on a suite of pieces dedicated to the dead when he was asked to write an actual Requiem by his French editor, Durand.

Duruflé accepted, immediately implementing his already-formed idea of combining the ancient world, and its Gregorian melodies – perfectly in accord with the recommendations of Pius X’s Motu Proprio of 1903 (as with his later Quatre Motets sur des themes grégoriens pour choeur a cappella, Op. 10) – with a modern harmonic setting and orchestration typical of the 20th century. His neomodal inflexions hark back particularly to the music of Debussy and Ravel. He in fact declared the orchestral work by Debussy Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune to be a masterwork he “adores”.

In a direct statement by the composer about his Requiem, he affirmed:

“My Requiem is entirely constructed on Gregorian themes from the Mass for the dead. At times the text is uppermost in importance, and therefore the orchestra is there to support or provide a commentary on the meaning of the words. At other times an original musical backdrop, inspired by the text, takes centre-stage.”

Gregorian chant, modality, compositional style rich in counterpoint and modern harmonies, originality, power and aesthetic and expressive beauty allow performers the opportunity for very sensitive musical interpretation and rhythmic freedom, which results in a natural and extremely smooth flow in the text and the music.

As previously mentioned, Duruflé chooses to continue an aesthetic style initiated by Fauré, with an intimate and restricted orchestration. Even in the forte or fortissimo moments, there continues to be felt a quality in the music, both polyphonic and harmonic, of profound delicacy and refinement.

The Requiem is made up of nine movements, each with a tripartite structure: Introit, Kyrie, Domine Jesu Christe, Sanctus, Pie Jesu, Agnus Dei, Lux Aeterna, Libera me and In Paradisum.

Like Fauré, Duruflé has the Domine Jesu Christe and the Libera me sung by a baritone soloist and the Pie Jesu by a mezzo-soprano.

Although both composed their Requiem in D minor, in Duruflé’s version the tonality ranges more widely, and is also more modal and modern.

The first version for choir, organ and orchestra was written in 1947 and it is said to be the version preferred by the composer. In 1948 he wrote the second version for choir and organ, with the intention of allowing this work to be used by choirs in churches. In the same year he also wrote the third version for choir, strings, organ and optional parts for harp, trumpets and timpani.

Musical Analysis

(For illustrative purposes, we are confining our attention here to the version for choir and organ – Introit and Kyrie – believing it to be the most suitable for the member choirs of AERCO (Regional Association of Choirs) and provincial choral associations)

Introit

The structure of this movement is in the typical A-B-A ternary form.

The first chord is in D minor with the seventh (I7). This ensures that the harmony is ambiguous right from the beginning. We can definitely interpret this start within a “modal” framework. The accompaniment goes into an arabesque which in fact dissolves the tonic seventh, with neighbour notes and passing notes on B flat and G.

The tonal ambiguity we encounter right from the start is also due to the fact that entrance of the male voices faithfully echoes the Gregorian melody in the key of F (VI mode Hypolydian mode). For the listener this therefore creates a melodic harmonic progression which alternates between D and F.

This progression is also found in the long finale of this movement which actually ends in F major and also faithfully follows the Finalis of Gregorian melody.

Bar 56 – end of movement:

The complex harmonic structure moves through the Doric (D), Aeolian (A), Phrygian (E) and Mixolydian (G) modes, to end finally in the Hypolidian (F).

From the point of view of metre and rhythm, Duruflé faithfully recreates the smooth flow of the delivery of the text, freely alternating two-beat and three-beat bars, simple and compound time, irregular forms. From the point of view of performance therefore, it is important to pay attention to following the natural accents of the liturgical text, to continue expressing and recalling the style of delivery and Gregorian mood of this passage. Care should be taken, for example, right from bar 2, where the male voices come in on the second beat with the word Requiem. This start is not to be interpreted as a headlong attack. This way, one would fall into the trap of accenting the final syllable of the word Requiem (-èm) which would upset all the melodic and prosodic phrasing. The correct emphasis in the word Requiem is in fact on the first syllable (Rè-)

The second section (from bar 24) begins in A minor and broadly in the Aeolian mode.

The cadence Vm-I confirms this at the end of the phrase, without using the leading tone G#.

Duruflé does not change the key modifications, perhaps leaving them there to remind us that the complex tonal structure is still in D (minor) and F (major). However whether it is in the writing or the listening, the recitative, this time in the hands of the sopranos, alternates systematically between the mother-chords of A and C, maintaining the original Gregorian melodic profile, but putting in a third over the top and moving from the Hypolydian (F) to the Aeolian (A).

Duruflé inserts a subtle new element with the triplets.Together with the metric variation, highly dynamic and interesting phrasing is created despite the fact that the melody is concentrated on the two notes of A and C, with the only passing note B (natural).

At the end of this Section, the original theme returns, but Duruflé has a new way of presenting the reprise. It is a simple variation which enables the new element to be heard, but at the same time faithfully reprises the first part. He gives the organ the Gregorian theme (still accompanied by the arabesque and pedals as in the first Section) and has the text Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine sung by the male and female voices in unison on the repeated notes of C, D, C again and A. In this way the organ enters fully into dialogue with the choir, as if it was itself a second choir.

This is also an example of what Duruflé himself stated, namely that “the orchestra (in our case the organ) is there to support or provide a commentary on the meaning of the words”.

This involvement means that, on the one hand the listener is recalled to the text and the original Gregorian melody via the instrumentation, and on the other they can hear the choir (which continues the recitative just gone in the second Section), in perfect and consistent polyphonic and textural connection.

Kyrie

The structure of this movement is practically identical to the one before: A-B-A ternary form.

Duruflé joins the first movement directly to the second via the instruction Enchaînez (continue without pausing), emphasising the feeling of continuity between the two pieces. The second movement in fact starts immediately.

This time, rhythm and tonality remain fixed and definite from the beginning to the end: 3/4 and F major. The reason for this may be motivated by the fact that the intense and complex polyphonic structure is given over exclusively to the internal development of the choir and organ which interacts directly and continually with the voices. Choir and Organ become as one.

Duruflé starts with the basses, recalling the original Incipit of the Gregorian melody in the word Kyrie, then goes on to develop his entire complex counterpoint.

Following the exposition of the subject by the altos and sopranos, a organ comes in as a fifth voice. It is once again the Incipit of the Gregorian melody (doubled at the octave) on the word Kyrie, this time used in the form of Cantus firmus.

This has the undeniable intention of reinforcing the original Gregorian melody.

Bars 10-16:

Here Duruflé finds a clever way to develop his polyphonic, contrapuntal creativity and at the same time remain faithfully anchored to his choice of original source.

The combination of harmonies which are created by the vigorous movement of the voices freely creates a number of ‘dissonances’, which are always however ‘natural’ and appropriate for the polyphonic texture used.

In the second Section, on the words Christe eleison, Duruflé chooses this time to compose of a new melody. His starting point is the melodic line of the word eleison, which he then develops creatively and openly.

As in the first movement, in this second Section we again shift into A minor (which recalls the Aeolian mode) with just the female voices in continuous imitation of each other.

The reprise dovetails in with the basses powerful ff on the word Kyrie in the last bar of the sopranos and altos singing the word Christe.

The final Section starts in imitation at the fourth (tenors), at the fifth (altos) and again at the fourth (sopranos) in a textural crescendo which leads to the ‘climax’ of the movement in bar 58, with the sopranos who end on the accented A flat.

In this part the F major harmonies are also occasionally coloured by the inclusion of the E flat, which seems to suggest a movement towards B flat major, without ever modulating in any real sense to this key.

Composers also often employ the flattened seventh to avoid or reduce as far as possible the use of the leading tone which would give the listener a more traditional classical musical experience.

Once the climax has been reached, as in the first movement, there is a gradual loosening of the overall vocal and instrumental texture, which ends once again with a long tonic pedal – the choir ends up on a perfect chord of F major, meant to be understood once again (as in the first movement) as the Finalis, the final note of the original Gregorian melody – which is cleverly achieved with a melodic ascending movement of the bass, thus avoiding the functional formula of classical cadences, such as the V-I.

Even in the final two bars of the cadence V-I, Duruflé shies away from using the leading tone, thereby giving the notes he chooses to use a more modulatory than tonal quality.

Performance suggestions

Even though the entire Requiem has been written with dynamics ranging from ppp to fff, it is important to focus on producing a performance and an interpretation which are delicate and refined above all else. The contrapuntal writing directs us towards a style of singing (with voices which are always well supported and fluid, without being too lyrical) and playing which are “flowing and smooth”.

Over-singing in the forte passages, and too much falsetto in the piano and pianissimo passages would certainly result in something too heavy, static and would fail to convey correctly or adequately the complex polyphonic and textural structure which Duruflé presents.

From the point of view of prosody, Duruflé himself, taking as his example Gregorian chant and the approach of the Benedictine monks of Solesmes, suggests that it is vital to sing in accordance with the natural accents of the text.

This approach will ensure a smooth text, enhance the phrasing and will also allow greater articulation of the expressive meaning of the spoken words.

The instrumental accompaniment is designed to help with this, often using arpeggios and arabesques which encourage singing in synchrony with the fluidity of these musical figures.

Regarding the voices, it is important to try and perform the individual parts of the section perfectly in unison, striving as much as possible for an integrated vocal timbre, avoiding individual timbres which differ too much between themselves which may lead to ‘beats’ (i.e. different oscillations in frequency on the same note) and will mean that the overall pitch of the choir suffers through lack of precision. This is even more vital in polyphonic and harmonic passages containing lots of dissonances.

We conclude this article dedicated to the Requiem, Op. 9 with an interesting testimony by Duruflé himself who writes a letter to Director George Guest, Welsh organist and choirmaster of St John’s College, who made many recordings in the 1970s, including of this work:

Paris, 3rd April 1978

Dear Sir,

The management at Decca Records has kindly given me your address. It is a great pleasure for me to send you my sincere thanks and congratulations on the excellent recording which you were kind enough to do of my Requiem.

I very much appreciate the quality of the performance, the interpretation and the sound itself.

If you have the opportunity to conduct my Requiem again the future, might I say that I would prefer it if the baritone solos are sung by all the basses and second tenors.

It is an error on my part to have given these few bars to a soloist.

Once again, with all my thanks etc etc.

Duruflé, 6 Place du Panthéon, 75005 Paris

Translated by Laura Massey, UK

This article has been previously published on FARCORO, the Magazine of AERCO (Emilia Romagna Association of Choirs)