Das gemeinschaftliche Singen in der traditionellen afrikanischen Medizin: das Beispiel Westafrika

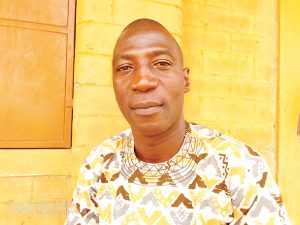

Sylvain Kwami Gameti, Togo

Sylvain Kwami Gameti, Togo

Chorleiter

Einleitung

Die Tradition des Chorgesanges ist stark verwurzelt in Afrika. Afrika hat eine musikalische Seele, ein musikalisches Bewusstsein und eine musikalisch überlieferte Tradition. Die afrikanische Musik erfüllt Aufgaben in den traditionelle Gesellschaften, die weit über das Glück hinausgeht, das sie den Völkern bringt, wo sie in allen Lebensbereichen gegenwärtig ist. Die Praxis des gemeinsamen Singens in seiner volkstümlichen Art ist eine sehr alte Spezialität der indigenen Völker im Herzen Afrikas, schon bevor Afrika den Chorgesang in seiner aktuellen Form durch die Kolonisation entdeckt. Für den Afrikaner, der nicht gerne alleine lebt, alleine arbeitet oder sich alleine vergnügt, ist die Ausübung der Musik vor allem eine Angelegenheit der Gemeinschaften und selten eine des Individuums. Sei es auf politischer Ebene, soziokultureller, ökonomischer oder religiöser Ebene, der Gesang hat immer Gruppen und Menschenmengen mobilisiert. Diese Praxis in der Gruppe oder Masse, welche später in den Chorgesang mündete, so wie wir ihn heute praktizieren, brachte viele Vorteile für die Völker, die sie überlieferten. Einer der Vorteile war die physische, moralische oder emotionale, psychologische und spirituelle Gesundheit. Wenn man Afrika kennengelernt hat als den Kontinent der Freude und der guten Launen, so verdankt es das vor allem seiner Praxis des gemeinschaftlichen oder chorischen Musizierens. In diesem Artikel werden wir den (chorischen) Gesang im Rahmen der traditionellen Medizin vorstellen, und wir werden zeigen, dass er ein wirksames Mittel gegen die meisten gesellschaftlichen Übel darstellt. Wir werden dies anhand von stichhaltigen Beispielen belegen, die der gelebten Wirklichkeit der traditionellen Völker Westafrikas entnommen wurden, als da sind: die Ewé, die Fon und die Ashantis vom Golf von Guinea, aus Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, der Elfenbeinküste, die Mossi, die Gourma und die Peulhs aus dem Sahel (Burkina Faso, Niger, Senegal, Benin im Norden, Togo, Ghana und Elfenbeinküste).

Wir werden zugleich Details über die therapeutische Rolle im besonderen aufführen, die den afrikanischen Chorgesang auszeichnet und damit in so viele Herzen weltweit dringt.

Der afrikanische Chorgesang, eine multifunktionelle Therapie

Es ist allgemein anerkannt, dass Musik psychosomatische Krankheiten heilt. In Afrika kommt dem Chorgesang das Privileg zu, eine der am meisten eingesetzten und wirkungsvollsten Musikformen im Rahmen des Musiktherapie zu sein.

Auf physischer Ebene basiert die afrikanische Musik ganz wesentlich auf dem Rhythmus. Daher eröffnet sie viele Möglichkeiten für Tänze bei einem reichen Angebot an stark akzentuierten Rhythmen. Da also die afrikanischen Gesänge fast immer durch Tänze begleitet werden, kommen die Sänger auf vielfältige Weise und häufig (zwei- bis dreimal, sogar viermal in der Woche) in Bewegung. Diese Bewegungen beinhalten eine ganzheitliche Körperarbeit und halten die Sänger somit gesund und bei guter Laune; das ist der Fall bei dem Tanz «Adzogbo» bei den Ouatchi und Mina aus Togo und Benin; und «Agbadza» bei Ewé (Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Elfenbeinküste).

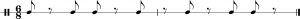

Vorstellung des Rhythmus Adzogbo:

Ein Rhythmus für abgezählte Tanzschritte, mit akrobatischen Pirouetten. Die rhythmische Abfolge ist sehr eigenartig und wird von folgenden onomatopoetischen Geräuschen begleitet: djan, djan, djan.

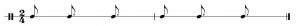

Vorstellung des Rhythmus Agbadza:

Ein eleganter Rhythmus, der einen Tanz hervorruft, bei dem die oberen und unteren Gliedmaßen bewegt werden und vor allem die Rückenmuskeln, woraus sich sein Name ableitet: dzimé wé (Rückentanz). Er lässt sich wie folgt notieren:

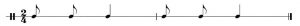

Kontcheng ist ebenfalls ein Rhythmus, der eine Bewegung des Körpers auslöst. Es handelt sich um einen schreitenden Rhythmus, der (beim Tanz) in einer Linie oder im Kreis ausgeführt wird, wobei man mit dem Kopf und Körper wackelt, wie der Schwengel einer Pumpe. Notation: Achtel, Achtel, Viertel – Achtel, Achtel, Viertel.

Auf moralischer und emotionaler Ebene verbessert der afrikanische Chorgesang, der viele Menschen zusammenbringt, die Stimmung der Sänger durch die besänftigenden Worte des Gesangs und bringt sie ins Gleichgewicht. Er bietet den Sängern ebenfalls eine sehr geschätzte menschliche Erfahrung. Wut, Depression und Neurosen werden vermieden, Sorgen werden zurückgelassen und Frieden und Ruhe in ihr Herz gebracht: genau das, was für eine strahlende moralische Gesundheit gebraucht wird. Dazu kommt noch die kathartische Funktion des Liedes, das, über den Zauber der Harmonien, die Herzen der tiefbetrübten Personen beruhigt.

Auf psychologischer Ebene verjagt das gemeinsame Singen die Angst und bestärkt bei den ausführenden Sängern Tugend und Tapferkeit, was ihnen Mut, Freude und Selbstvertrauen verleiht.

Auf religiöser und mystischer Ebene glauben die Afrikaner, dass der Gesang über eine magische, geheimnisvolle und unfehlbare Macht verfügt, Dinge zu bewirken, wodurch er erwünschte Ergebnisse erzielen kann. Daher wird er eingesetzt, um auf Tiere, Menschen und Dinge zu wirken. Die traditionelle Medizin nimmt häufig gesungene Zaubersprüche zur Hilfe gegen Schlangenbisse, gegen Krankheiten, um mit Geistern zu kommunizieren, Tiere zu zähmen, um Wut und Rachegelüste zu befriedigen, Regen oder gutes Wetter zu erhalten, Gespenster zu beschwören, Tote auf die Erde zurückzuführen, Dämonen zu jagen oder zu befrieden. Die Ausübung des Gesanges stärkt die Spiritualität der Sänger und gewährt ihnen Schutz vor den bösen Geistern. Der Gesang ist Teil der Heilung und Teufelsaustreibung. Die Wirkung der Menschenmenge, die den Chorgesang erzeugt, setzt Energie frei; eine übernatürliche Macht, die Krankheiten heilt, den Zorn lindert und die Dämonen verjagt. In diesem Sinne ist der Gesang ein echtes Heilmittel in der traditionellen Medizin Afrikas.

Der (chorische) Gesang, ein Heilmittel gegen psychosomatische Krankheiten in Westafrika

Die Musiktherapie ist keine neue Kunst in den afrikanischen Traditionen. Diese Praxis, die bis in die frühe Vorzeit zurückgeht, ist auch heute in der traditionellen westafrikanischen Gesellschaft aktuell, wo die Musik mit der Heilung von Krankheiten in den Klöstern mit Fetischen und bei initiatorischen Zusammenkünften verbunden wird..

Nach dem traditionellen Konzept wird die physische Welt von der Welt der Geister regiert. Alles Gute, das geschieht, hat seine Ursache im Segen der Götter; das Böse rührt von ihrem Zorn, ihrer Strafe oder ihrem Fluch. Die Heilung wird durch Anrufung der Geister bewirkt. Die Zauberheiler stehen in Kontakt mit den Geistern, die sie anrufen, um ihre Unterstützung für die Heilung einer Krankheit zu erflehen oder für die Aufhebung eine Verwünschung.

So fragen die Priester oder Seher im Falle seltener oder unbekannter Krankheiten um Rat in Form gesungener Zaubersprüche, um die Natur, den Ursprung und den Grund des Übels zu erkennen, um es bannen zu können. Der Kontakt zwischen den Menschen und Geistern wird über spezifische Gesänge mit melodischen Formeln und genauen bestimmten Rhythmen hergestellt. Diese Gesänge werden meistens von dem Priester oder dem Zauberheiler angestimmt, die dann in responsorialem Stil von einem Chor von Adepten abgelöst werden. Manchmal sorgt eine besondere Begleitung mit Schlaginstrumenten dafür, den Heilungsprozess zu beschleunigen. Dadurch wird die schnellere Erscheinung der Geister provoziert, die unvermittelt ins Geschehen eingreifen, indem sie die Leute in Trance versetzen und somit dann die Ursache der Krankheit enthüllen, sowie das Heilmittel, das je nach Fall anzuwenden ist. Die Spannweite der Heilmittel reicht von einem einfachen Kraut, das unter Gesang zu verabreichen ist, bis zu einen Exorzismus, der über mehrere Tage zu erfolgen hat.

In bestimmten Fällen, bei den Anhängern des Voudou, muss der Kranke, um gesund zu werden, nach einem bestimmten Ritual zu den von einem Fetisch vorgeschriebenen Rhythmen während eines festgelegten Zeitraumes tanzen und singen (drei Tage, einen Monat oder sogar drei Monate), in Abhängigkeit von der Schwere der Krankheit.

Unter diesen Umständen hängt es von der Qualität der Lobgesänge oder Beschwörungen und der Hingabe der Patienten ab, welchen Grad der Heilung letztere erreichen werden. Wenn der Patient aufgrund der Schwere der Erkrankung nicht selbst tanzen und singen kann, werden die Mitglieder der Familie gebeten, es an seiner Stelle zu machen. Sobald die Gottheit oder der Fetisch die Lobpreisung annimmt, erfolgt die Heilung.

Die Anwendung der Musik für die Aufhebung von Verzauberungen und die Heilung ist im westlichen Afrika sehr verbreitet und vollzieht sich in unterschiedlichen Formen je nach Volksgruppe oder Bräuchen. Weil dieselben Völker sich über drei oder vier Länder verbreitet haben, findet man häufig dieselben Lieder und Gebräuche in verschiedenen Ländern.

Gewisse Lieder zum Exorzieren oder zur Heilung, die sich als besonders wirkungsvoll erweisen, sind oft in den Sprachen eines Fetisches geschrieben, die nur die Eingeweihten verstehen. Die Priester verwenden diese Sprachen musikalisch beim traditionellen Psalmodieren und bei den gesungenen Prophezeiungen, um die Geister anzurufen.

Im Golf von Guinea wird der Yévégbé (Sprache des Gottes Yévé, eine Entsprechung zum Gott Jahve bei den Christen), von den Eingeweihten im Süden Nigerias, in Benin, Togo und Ghana verstanden. Sie benutzen diese Sprache, wenn sie unter sich bleiben wollen. Manche gesungenen Heilungen werden von herumziehenden Magiern vorgenommen, die ebenfalls die Stelle der traditionellen Priester einnehmen können.

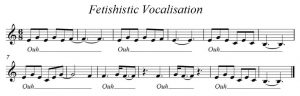

Eine kleine Beschwörungsformel der Gottheit Yéé

Einige fetischistische und mystische Rhythmen

Tadenta: ein herausragender fetischistischer Rhythmus, in den Klöstern sehr verbreitet. Hier wird er wie folgt notiert: Achtel, punktierte Achtel, punktierte Achtel – Achtel, punktierte Achtel, punktierte Achtel..

Habiyè: Rhythmus Kabyè (Volksgruppe im Norden von Togo, Benin und Ghana und Tschad) angewendet bei mystischen Tänzen. Sein Name wird auf die gesamte Vorführung angewendet, während derer man Zeuge wahrer Wunder wird, die von verborgenen Kräften bewirkt werden. Von ihm leiten sich wundersame Erleichterungen und Heilungen ab. Hier die Notation des Rhythmus: Achtel, Achtel, Halbe; Achtel, Achtel, Halbe.

Praktische Fälle der Heilung durch den Gesang der traditionellen Religion

Die Anhänger der Naturlehre erklären, dass einzig das Wort oder das gesungene Wort (Lied) einen Menschen heilen kann. Um das zu erreichen, muss man in die Person des Kranken eingehen und sein Übel oder seine Last auf sich nehmen, dann muss man den Natur-Geist der Heilung anrufen, dass er zur Heilung erscheine.

Der Musik-Heiler konzentriert sich und singt. In Wirklichkeit erfolgt die Heilung durch Substitution (Austausch/Stellvertretung). Der Heiler bewirkt durch seine gesungenen Zauberformeln, dass die Seele den Kranken verlässt und sich in seinem eigenen Körper niederlässt. Und folglich singt, wenn der Musik-Heiler singt, in Wirklichkeit die Seele des Kranken in ihm. Wenn es also der Seele des Kranken gelingt, im Körper des Musik-Heilers zu singen, dann kann er gesund werden.

Wie funktioniert das? (der Mechanismus)

Man platziert den Patienten zwischen sieben Personen, die die sieben Gottesgeister oder die sieben Gottheiten repräsentieren. Der Musik-Heiler, der die Namen der Geister gut kennt, beschwört sie mit seinen gesungenen Zauberformeln und schickt sie in den Körper des Patienten. Diese Geister wirken im Körper des Kranken und stellen seine Gesundheit wieder her, bevor ihm seine Seele zurückgegeben wird. All das spielt sich während einer Abfolge von musikalischen, vornehmlich vokalen Vorführungen statt.

Das Prinzip der Heilung durch die traditionelle Musiktherapie

Man muss unbedingt die Seele der Person von der umgebenden Welt trennen, um sie auf eine astrale Reise zu schicken und sie durch die Seele eines anderen zu ersetzen (häufig mit der Seele des Heilers selbst und derjenigen eines reinen Unschuldigen oder eines Heiligen). Die Absorption oder die Entfernung der Seele des Kranken erfolgt unter Gesängen und der Anrufung der Geister, die ihn aufsuchen und für ihn sorgen, während sein Körper unter Mitwirkung anderer Geister dabei ist zu gesunden. Jeder der angerufenen Geister spielt eine besondere Rolle im Heilungsprozess. Je nach Fall und Schwere des Übels ruft man 3, 7, 14 oder 17 Gottheiten an.

Der Fall des Schlangenbisses

Im Falle eines Schlangenbisses ist es notwendig, die Gottheit “Voudou Dan” anzurufen, indem man sein Lied aufführt. Die Gottheit kommt und heilt über die Substitution auf wundersame Weise den Kranken. Das internationale Heiligtum der Gottheit Dan befindet sich in Ouidah in Benin.

Es gibt auch Heilungen durch den Gesang über einen längeren Zeitraum. Man beginnt mit Gesprächen. Danach schreibt man dem Kranken vor, zu singen und zu lächeln. Indem er sich an diese Vorschrift hält, wird er am Ende gesunden.

Zusammenfassung

Die traditionelle afrikanische Musik ist vor allem ein klanglicher Reflex der kulturellen Gegebenheiten der traditionellen afrikanischen Gesellschaften. In diesem Sinn ist sie wirklich Teil der Heilmittel gegen mehrere Übel in der Gesellschaft. Man wendet sich in den Gesängen an die Gottheiten oder Geister und bittet sie um Hilfe bei der Heilung. Die Heilung erfolgt immer und ausschließlich über die Substitution unter der Wirkung der speziellen Musik aus gesungenen Zauberformeln, die es gestatten, mit den Gottheiten und wohltätigen Geistern zu kommunizieren. In diesem Bereich spielt die chorische Musik, die eine sehr lebendige kollektive Praxis darstellt, die Rolle der Vermittlung oder des Antwortchors auf die Soli des Heilers. Die Klöster Nogokpo und Essem in Ghana und das von Parakou in Benin sind sehr geschickt in dieser Art der traditionellen, regionalen Musiktherapie.

Anhang

Einige Heilgesänge

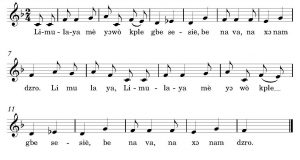

Limulaya

- Lied der Anrufung der sieben Geister oder Gottheiten

- Sprache: Ewé

- Übersetzung: Limulaya, ich rufe dich mit lauter Stimme an, damit du kommst, mir zu helfen.

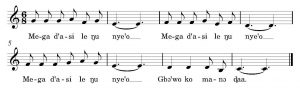

Mega d’asi le nu nye o.

- Übersetzung: Verlass mich nicht, ich werde immer nahe bei dir leben.

- Sprache: Ewé

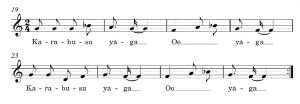

Karabusu

- Anrufung der Geister Yévé, Hebieso, Lissa, Sogbo, Patapa, damit sie kommen, um zu handeln.

- Sprache: Ewé vermischt mit Hindu.

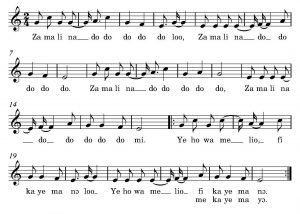

Zamalina

- Anrufungslied des göttlichen Yévé.

- Sprache: Yévé (Sprache der Gottheit Yévé)

- Übersetzung: Wenn Yévé oder Jehovah nicht da wäre, wo wäre ich?

Sylvain Kwami Gameti, ehemaliger künstlerischer Leiter des Chores der Universität Lomé (Togo) von 1996 bis 2003, ist Leiter des Chœur National du Togo seit seiner Gründung im Jahre 2009; er hat die wechselnde künstlerische Leitung des Chœur Africain des Jeunes während vier Jahre organisiert, und seit Mai 2018 ist er Koordinator des Projektes «Chœur Africain des Jeunes» innerhalb der Confédération Africaine de Musique Chorale (Afrikanischer Verband der Chormusik). Mit seinen Chören war er auf Konzertreisen in Frankreich, Spanien, Südkorea und Deutschland; er hat an mehreren Festivals für Chormusik in mehreren afrikanischen, europäischen und asiatischen Ländern teilgenommen. E-Mail: sylvain.gameti@gmail.com

Übersetzt aus dem Französischen von Manuela Meyer, Deutschland