The Madrigal and Rhetorical Figures

by Lucio Ivaldi, choir director and teacher

1) Introduction

The medieval notion of the seven liberal arts included rhetoric among the ‘lower’ disciplines of the trivium, or homiletic arts, alongside grammar and dialectic. By contrast, the four ‘high’ arts of the quadrivium, the royal arts, were astronomy, music, mathematics and geometry.

Ancient musical treatises, from those of Boethius and Isidorus to that of Tinctoris, gave a theocentric and allegorical explanation of the structure of musical discourse. Music, the harmony of the spheres, was the noblest of the arts of the quadrivium and its connoisseurs spoke of heights and intervals. The forms of knowledge connected with the arts of the trivium were kept rigidly separate from those of the quadrivium.

The cultural challenge of humanism enriched the perspectives of the late medieval era. The liberal arts were reinvigorated by means of a fecund cross-pollination between the trivium and quadrivium.

An important date in the history of European culture is that of the discovery of Quintilian’s ‘Institutio Oratoria’ near the monastery of Saint Gallen, in 1416. Between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, this publisher produced around 150 different editions of Quintillian’s text, a number which – should we include the treatises, commentaries and musical tracts – reaches approximately 2000.

The new generation of musical theorists at the dawning of the sixteenth century felt it necessary to represent new, emerging musical forms, the techniques of polyphony, the temperaments of musical scales, and the innovations of musical notation. The challenge was to understand and describe the new state of artistic production, and not simply to dictate prescriptive and descriptive a priori musical norms.

The ground was being prepared for what would become, in Claudio Monteverdi’s longsighted vision, the so-called second practice. Thinking about music without the assistance of the three ‘low’ arts became impossible.

So, musical theorists welcomed rhetoric into their own treatises: Nikolaus Listenius with Musica Poetica (1537), Gallius Dressler with Praecepta Musicae Poeticae (1563), and the influential Joachim Burmeister, who published his Musica Poetica at Rostock in 1606. We cannot cite all the treatise writers, but we cannot fail to mention Johannes Lippius, Joachim Thuringus, Athanasius Kircher, Christopher Bernhard and, last only in chronological order, Johann Mattheson, who published Der vollkommene Kapellmeister in 1739.

2) Poetic Procedures and the Parts of Discourse

Like Quintilian in his Institutio Oratoria, which proved to be so important for the humanistic definition of the poetics of literary forms, Burmeister systematically addresses musical discourse, offering, above all a description of the logical procedures involved in the process of transmission from the composer to the audience through the performer.

The four procedures he proposed are:

- Inventi: identifying the subject matter of the new work and sketching out its principal musical ideas;

- Dispositio: elaborating and arranging in space and time what has been invented;

- Decoratio: completing the formal matter of the piece, using a panelling technique that consists in implementing the doctrine of the figurae, which we will explore below; and

- Pronuntiatio: the art of elocutio or musical execution with all the necessary expressive and technical means.

The discipline of dispositio involves dividing the discourse into six parts:

- Exordium, or captatio benevolentiae: capturing the listener’s attention;

- Narratio: announcing the argument at hand;

- Propositio: exposing the main thesis;

- Confirmatio: substantiating the thesis;

- Confutatio: describing and refuting opposing theses; and

- Conclusio: providing the concluding summary and final peroratio.

In Mattheson and other authors’ works, there is a different disposition of, and nomenclature for, the different parts; the reversal of confutatio and confirmatio gives greater emphasis to confirmatio, which is undertaken only after having refuted the opposing arguments.

When analysing musical scores, Dressler’s tripartite division is useful:

- Exordium,

- Medium, and

- Finis.

Note how this subdivision mirrors Aristotle’s tripartite division into parodos, stasimon, and exodos, as well as Cicero’s stylistic functions: movere (to move), docere (to teach) and delectare (to enjoy).

Moving on to decoratio, we note that Burmeister and other theoreticians propose a series of figures which associate poetic and musical procedures with various desired effects. This is a complex and often difficult subject for study. One recent comparative study, which considers all historical treatises, classifies more than 400 figures. Here below, we will examine only fifteen, those most common to the madrigal repertoire, without neglecting the fact that the doctrine of the figures, the Figurenlehre, is also very important in analysing instrumental repertoires and the intentions of composers in the late baroque period.

3) Some of the principal musical figures

An important general consideration is that the figures can be endlessly re-arranged; they do not respect the logic of separation and individuation (as do, by contrast, the parts of discourse in the dispositio) They are rather more like the colours a painter uses as he prepares to create visual detail. Thus, it is not unusual to find four, five or six figures superimposed in a musical passage.

- Anaphora. The simplest of the figures It describes the generic repetition of a fragment, whether melodic or textual. According to the contrapuntal procedure used, this figure may take numerous forms: anadiplosis, analepsis, polyptoton, etc.

- Antitheton. Conceptual opposition (e.g. slow/fast, high/low, loud/soft) It is often termed an oxymoron in the rhetoric of literary texts. The baroque musicus found ample satisfaction in the musical implementation of the poetical oppositions and chiaroscuro visual effects in madrigal texts.

- Aposiopesis. The great fermata of the discourse, the pause.

- Auxesis. Although quite varied in its use among different treatise writers, this term normally refers to ascending movements in the melodic lines, as in auxesis, climax and gradatio, and to the opposing moments of descent, as in minuthesis or anticlimax. The highest point of a composition, not only in its musical line, but also in terms of volume and density, it is also referred to as climax.

- Congeries. A widely spread procedure in both vocal and instrumental baroque music It is a successive concatenation of root position chords with first inversion chords.

- Fugue. In the face of mutations accrued over the span of successive centuries, and of historically unsupported teachings, this figure requires clarification. According to ancient usage, the fugue is not a musical form but a poetical procedure, a playful image, in which two or more voices chase each other. It can be either imaginaria or realis. Here, too, the definitions can give rise to inaccuracies when confused with the “official” nomenclature of musical theory. The fugue is characterised by a lead voice, dux, which sets forth a motif, and by a secondary voice, comes, which follows the lead voice. The fuga imaginaria is a geometrical construct, according to which the voices imitate each other, employing all the artifices of counterpoint. The fuga realis, on the other hand, involves a playful succession of voices, in which the interspersed content and the melodic line shared between dux and comes playfully and freely reflect each other in a more or less mirror-like way, as in a divertimento.

- Hypallage. Contrapuntal use of the opposed movement, or of the reversal or retro-gradation of musical elements.

- Hypotiposis. This is not just one figure but a whole category of figures. It corresponds to so-called madrigalismo, that is, musical painting. Here, the musical and conceptual content to be represented is created through spatial visualisation. Anabasis involves the ascent of the melody towards higher frequencies; katabasis, its descent; circulatio, a circular procedure that neither ascends nor descends; suspiratio, the imitation of sobs and sighs. The composer indulges his fantasy in these figures. In many cases, the enthusiasm for graphical representation pushes the musical notation towards peculiar graphical effects; for example, the rendering of the word “eyes” by two juxtaposed white notes. Bach, arranging the parts of the Hohe Messe, literally draws a cross to represent the word “crucifixus”.

- Interrogatio, Exclamatio. One of the fundamental points of the Affektenlehre, this involves imitating the human voice and the emotional states it expresses. The ascending melodic line that typifies questions is musically imitated by means of an ascending interval, followed by a pause. Similarly, in the exclamatio, assertiveness is expressed by means of a wide interval (generally more than the minor sixth).

- Metalepsis. As in the case of the literary figure, while performing the sung text of a passage, one of the voices sometimes enters into a musical discourse that has already begun, without repeating the portion of text already sung. The complex meaning of the text can be understood only by someone who has listened to the succession of voices in their chronological order.

- Noema. A homorhythmic moment for the vocal group The complete text is set forth and clearly pronounced. It can be a single, double, or sequentially set forth enunciation, according to the structure of repetition in the piece. Where the rhythmic, but not the tonal, pattern of the musical motif is repeated (for example, by repetition on a different scale degree), this is called noema-mimesis.

- Passus, cadentia, saltus duriusculus. These involve passages, cadences or tonal leaps which give rise to the psychological perception of “difficulty”, stemming from intervals and harmonies. Technically, the saltus duriusculus envisages melodic displacements of an augmented fourth or sixth, while the passus duriusculus improvises modal changes and unanticipated chromaticisms. Bach makes frequent use of these figures, even in his instrumental music.

- Pathopoeia. One of the most important figures. In conjunction with moments of great emotion (pain, regret, death, etc.), it involves the musical painting of such feelings by means of diatonic semitones in one or more vocal parts at the same time.

- Pleonasmos. A superabundance of harmonic and contrapuntal procedures. It characterises the clausulae of the late-renaissance and baroque periods, enriched, in contrast with those of the medieval period, by a series of contrapuntal figures, which the scope of this article only allows us to list briefly: Symblema, Syneresis, Syncopatio, etc.

4) Analysis of a Madrigal

Below is an analysis of Quando i Vostri Beli’ Occhi from Luca Marenzio’s first book of madrigals for five voices (1580), on a text by Jacopo Sannazaro (1458-1530). We will proceed without a musicological introduction, simply applying Burmeister’s criteria from Musica Poetica, and limiting the repertoire of figures to those listed above.

This approach follows and includes that proposed by Unger in his text, Musica e Retorica (see bibliography). In several cases, however, our conclusions differ from Unger’s. The analytical use of rhetorical figures, far from being an exhaustive system, permits a remarkable degree of liberty and subjectivity in identifying the procedures in the dispositio and decoratio.

Above all, it is important to read and understand the poetic text. This text places emphasis on the inventio, the first compositional procedure, which coincides with the author’s choice of preliminary content, which is not described for our analytic purposes.

Quando i vostri begl’occhi un caro velo

Ombrando copre semplicetto e bianco,

D’una gelata fiamma il cor s’alluma,

Madonna; e le midolle un caldo gelo

Trascorre si, ch’a poco a poco io manco,

E l’alma per diletto si consuma.

Così morendo vivo; e con quell’arme

Che m’uccidete, voi potete aitarme.

The textual structure is that of the canzone, with a single stanza comprised of eight hendecasyllabic verses. The rhyme structure is abc abc de.

One is immediately struck by the accumulation of enjambments (i.e. syntactical prolongations of the meaning of one verse into the verse following). The textual rhythm flows quickly. The musical caesurae only make sense after the words, “Madonna,” “manco” and “consuma,” but would elsewhere provoke pointless ritardi. The rather wide separation of the internal rhymes (“semplicetto” and “diletto”) is musically quite rich.

Moving on to Burmeister’s second compositional procedure, we can attempt to reconstruct the dispositio of the poetic and musical content of this madrigal, one part at a time:

1-2) Exordium and Narratio. Here, as in other passages, the two parts of the discourse coincide. “Quando i vostri begl’occhi” from measure 1;

3) Propositio “e le midolle un caldo gelo” from measure 11;

4) Confirmatio “E l’alma per diletto si consuma” from measure 21;

5) Confutatio “Così morendo vivo” from measure 26; and

6) Conclusio “E con quell’arme” from measure 30.

However, subdividing the passage is simpler if we follow Dressler’s tripartite schema:

- Exordium;

- Medium from measure 11;

- Finis from measure 30.

As for the decoratio, Burmeister’s third procedure, we offer below a synthetic description of its various figures.

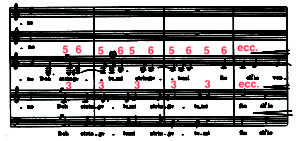

The piece opens with a classical, if somewhat archaic, bicinium, which corresponds to the fuga realis. The finale of the bicinium may be defined as a pleonasm, due to the intensification of the contrapuntal material.

In measure 4, the word “Ombrando” appears as a form of metalepsis, while bassus and tenor describe an evaded cadence. The musical superimposition of the two hendecasyllabic verses is a refined rendering the enjambment. The musical motif, if pronounced homorhythmically, constitutes a noema-mimesis, repeated in measure 6.

The internal rhyme that intersects measures 5-7 and 22-24 is rendered by noemae that employ the same rhythm for “semplicetto” and “per diletto”.

“D’una gelata fiamma” in measure 9 is a nice oxymoron using a harmonic passus duriusculus, thanks to an antitheton evidenced by the tonal distance between “gelo” and “fiamma”.

“Madonna,” in measure 11, constitutes a noema, but also exclamatio in the musical line of the bassus.

In measure 13, we find an effective use of hypotiposis in the word “trascorre,” with a circulatio.

From measure 15, we have a plethora of figures: antitheton of the conceptual content with respect to the preceding situation; harmonic congeries with a katabasis design; hypotiposis of the phrase “io manco”; fuga immaginaria between the altus and quintus; and noema-mimesis, inasmuch as the passage is repeated at measure 17.

In measure 20, the play on the semitone in “io manco” constitutes a pathopoeia, abruptly followed by an emotive interruption or aposiopesis.

Measure 21 is the rhetorical climax of the passage, occurring at the noema, “E l’alma,” then repeated as a noema-mimesis. The design incorporates internal rhyme, enacted with hypallage (moto contrario).

“Così morendo vivo” (from measure 26) is dense in figures, with an initial suspiratio, a passus duriusculus and hypotiposis of the word “morendo”, and antithethon and hypallage of the word “vivo”.

Finally, from measure 30 onwards, the voices begin to be stratified, that is, there is an incrementum upon a fuga realis, that sees anabasis and katabasis follow each other up to the pleonasm of measure 36. Here, we arrive at the final cadence, where the harmonic movement is clear and predictable.

5) Final note

Thanks to the Figurenlehre area of study, rediscovered in the 20th century and amply explored from 1908 in Arnold Schering’s publications, the study of musical rhetoric has given rise to extensive scholarship and significant aesthetic and musical appreciation. This article is the fruit of numerous bibliographic studies but I wish to attribute my interest in the discipline to Giovanni Acciai’s lessons and to the invaluable notes taken during his courses. This article is therefore dedicated to him, with appreciation and affection. Further study of this topic should certainly include Hans Heinrich Unger’s beautiful volume, cited in the bibliography, and which I highly recommend.

6) Bibliography of essential works

- Arnold Schering, Die Lehre von den Musicalischen Figuren, Regensburg, 1908.

- Ian Bent, Analysis, London, 1980.

- Enrico Fubini, L’Estetica Musicale dal Settecento a Oggi, Turin, 1964.

- AAVV, Musica e Retorica, Messina, 2000.

- Hans-Heinrich Unger, Musica e Retorica, Florence, 2003.

- Ivana Valotti, Cantantibus Organis, Bergamo, 2006.

- Giovanni Acciai, Le Composizioni Sacre di Carlo Gesualdo, Lucca, 2008.

- Finally, I also recommend visiting www.musicapoetica.net, where more than 400 literary and musical figures can be found.

Translated by Marvin Vann Griffith, USA

Edited by Hayley Smith, UK