Symphonies chorales de Mahler: Éléments philosophiques et techniques de mise en œuvre

Adamilson Guimarães de Abreu, chef de chœur

- Introduction

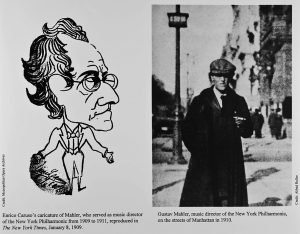

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) est considéré comme un maître en technique instrumentale et en orchestration mais sa musique chorale, en particulier dans ses symphonies, occupe au sein de ses œuvres une place prépondérante. Au fil du temps, la réputation de Mahler comme grand chef a contribué à sa reconnaissance en tant que superbe compositeur. De nos jours Mahler est considéré comme l’aboutissement d’une certaine lignée de symphonistes austro-allemands. Outre ses neuf symphonies dont cinq comportent un chœur et/ou des solistes vocaux, des œuvres très appréciées de Mahler sont une cantate profane et cinquante œuvres vocales (dont certaines orchestrées). Malgré la présence frappante de la voix dans les œuvres de Mahler, ses exégètes n’ont statiquement pas consacré autant d’attention[1] à cette écriture chorale qu’à son talent d’orchestrateur.

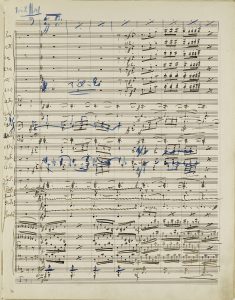

Les sources concernant Mahler abondent, et de nombreuses études sont disponibles. Le seul problème, comme on vient de l’écrire, est celui du manque d’intérêt spécifique: quelques-unes seulement sont directement, entièrement ou spécifiquement dédiées à ce traitement du chœur. Les plus pointues sont des études récentes sous forme d’articles ou de dissertations. À partune page web, toutes les sources que j’ai trouvées sont de ton didactique, et bon nombre d’entre elles sont relativement récentes, par des étudiants tant américains qu’européens qui soit racontent sa vie en long et en large soit dissertent sur tout autre chose que le chœur. C’est pourquoi mon travail a pour but de disséquer ces études, à la recherche de certains détails bien précis. D’autres sources pertinentes sont des apports personnels comme des lettres, des souvenirs, de l’iconographie ou des textes de programmes au sujet de Mahler et de ses proches. Et bien entendu, la musique même de Mahler sous forme de partitions et d’enregistrements est dans toute étude d’une importance primordiale.

La musique chorale de Mahler étant encore reléguée à une place secondaire, je me suis efforcé de rechercher des sources relatives au traitement du chœur dans ses symphonies N°2 (1895), 3 (1902) et 8 (1909), les trois qui comportent des parties chorales. L’accent a été mis sur les aspects musico-philosophiques et sur les éléments techniques de l’usage choral, car la mentalité et la philosophie de vie de Mahler sont inséparables de sa musique.

- Fondements philosophique et littéraire de Mahler

Pour mieux comprendre la musique de Mahler, il est capital de mettre en exergue sa philosophie de vie. Selon plusieurs exégètes[2] de ses programmes de symphonies[3], selon les grands penseurs de la littérature qui lui sont associés, il semble que les questions métaphysiques et eschatologiques faisaient étroitement partie de la vie de Mahler, tout autant que son action de compositeur. Constantin Floros abonde dans ce sens en écrivant:

Gustav Mahler est un de ces artistes dont l’art et la personnalité sont indissociables. Contrairement à ce qu’on pourrait penser, son écriture symphonique exprime sa conception du monde qui a un contexte littéraire et philosophique. Sa pensée religieuse et philosophique est inséparable de son œuvre.[4]

Ce sésame suggéré par Floros peut nous aider à voir en la psychologie de Mahler et son expression musicale la clé pour la compréhension de sa musique chorale.

La littérature et les gens qui y étaient associés ont joué dans le mode d’expression musicale de Mahler un rôle important. D’accord avec Floros, David Holbrook pose que “dans la littérature, nous n’avons au sujet des problèmes fondamentaux de l’existence rien d’aussi profondément impliqué que les œuvres de Mahler.”[5] Steven Johnson aborde plus en détail les philosophes Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) et Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), et le compositeur Richard Wagner (1813-1883), trois personnes qui “laissèrent leur empreinte” sur la musique de Mahler. Par exemple, Johnson évoque la dualité de pensée exprimée dans la 3èmesymphonie de Mahler, enracinée d’abord dans World as Wílland Idea[6] de Schopenhauer (1818), puis dans The Birth of Tragedy [7] de Nietszche. Selon Holbrook,”Mahler aurait observé une dualité semblable dans l’essai de Wagner avec Beethoven, qu’il salua un jour comme la perfection faite musique.”[8] Johnson suggère donc que l’appel de Wagner à un renouveau de l’esprit allemand via la musique de Beethoven était pour le jeune Mahler le fait le plus inspirant.[9]

Une autre figure littéraire cruciale pour le développement de la pensée philosophico-littéraire de Mahler fut Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Mahler admirait profondément Goethe, et était attiré par la scène finale l’acte II de son Faust,en raison de son lien avec des thèmes métaphysiques.[10] Mahler avait lu une biographie de Goethe, et tandis qu’il composait sa 8ème symphonie sa femme écrivit: “Goethe et les pommes sont les deux choses sans lesquelles il ne peut pas vivre.”[11] Il est clair que Goethe exerça sur la pensée de Mahler une puissante influence.

- Philosopher en musique

L’implication de Mahler envers le sens de la vie est la force la plus déterminante dans ses symphonies. L’écriture musicale était sa manière de philosopher, sa recherche de réponses aux questions fondamentales de l’humanité. Que sommes-nous ? Où allons-nous ? Quel est le sens de la vie ? Qu’y a-t-il après notre mort ? Le programme qu’il écrivit pour ses symphonies n’est rien d’autre qu’une tentative que les auditeurs comprennent le contenu spirituel de sa musique et appréhendent sa démarche personnelle de recherche de réponses aux questions primordiales quant à la vie.

Les préoccupations métaphysiques de Mahler reflètent l’angoisse sociologique de changement de siècle, aussi appelée existentialisme de fin de siècle, avec la dislocation de l’empire autrichien. Par exemple, Franklin cite plusieurs éléments inhabituels qui bousculent des concepts musicaux traditionnels comme des sonorités différentes, des effectifs orchestraux énormes, des niveaux dynamiques extrêmes, une dispersion spatiale des instruments, l’évocation de forces de la nature, et des formes identifiables de musique populaire. Tous ces aspects musicaux inhabituels interrogent, et remettent en question les acquis culturels datant de l’époque de Mahler.[12]

Un autre aspect évident de la fascination de Mahler pour la métaphysique, c’est la spiritualité résultant de son héritage juif, combinée à sa conversion ultérieure au christianisme (1897). Alma Mahler observa que “ses chants religieux, la 2èmesymphonie, la 8ème, et tous les chœurs des symphonies sont enracinés dans sa propre personnalité, et non plaqués de l’extérieur! Jamais il ne renia son origine juive… il était Chrétien-Juif.”[13] Cette imbrication d’effets littéraires, sociologiques, intérieurs et religieux se manifestent physiquement dans la musique de Mahler.

3.1 Transmettre en musique les matières philosophiques

Plus important encore qu’appréhender les motivations métaphysiques derrière la musique de Mahler, c’est mesurer les conséquences concrètes de la mise en œuvre de ces concepts musicaux. PourMahler,”la symphonie crée un monde, avec tous les moyens techniques dont on dispose[14] L’argument de Nietzsche peut avoir conduit Mahler à mettre en valeur de simples chants populaires comme le miroir musical le plus fondamental disponible au monde.

L’utilisation apparente par Mahler de formes populaires comme reflets du monde lui permet également de les transformer pour transmettre des traits personnels comme l’ironie. Henry Lea prétend que l’ironie de Mahler est freudienne, au sens où sa musique est hautement liée à la révélation d’une profondeur insoupçonnée.[15] Mahler emploie des formes populaires pour communiquer un message au-delà de l’intention fonctionnelle de l’art populaire. Ses marches, danses et chants populaires stylisés ont un objectif commun (unir les gens) transfiguré en une intention plus largement universelle sur la condition humaine.[16] Par exemple le chœur est une seule voix au sens où de constantes montées d’harmonie et de rythme, une orchestration savante et la qualité émotionnelle de la musique contrastent avec la piété du texte.[17] Mahler réalise son ironie musicalement en utilisant une forme collective pour exprimer précisément le contraire de son esprit habituel.

Étroitement lié à l’ironie est le sens qu’a Mahler de l’humour, qui transpire aussi de sa musique. Il est important de relever combien Mahler en place la barre haut. Comme il le dit, “l’humour doit servir à exprimer uniquement les choses les plus élevées qui ne peuvent pas être exprimées d’une autre manière.”[18] Son humour est présent à la fois dans le texte et dans son expression musicale, sans la moindre mise en péril du sujet sérieux global de ses symphonies dans leur ensemble.[19] Par exemple les paroles de Jésus dans le texte du 5è mouvement de la 3è symphonie sont rendus irrévérencieux par les indications de Mahler “grob” [grossier], un brutal forte, et un retour en fa majeur où Abbate voit un échec de la transcendance.[20] Et le chœur d’enfants, résonnant comme des cloches, a lui aussi un effet humoristique après la tension du mouvement qui précède.

3.2 Texte et idées poétiques

Il a été suggéré plus haut que Mahler a dans ses œuvres, et en particulier dans ses symphonies, un agenda humaniste. Beethoven a créé un précédent pour la musique chorale, avec un texte envoyant à l’humanité un message. Dans le même esprit, Mahler fait un pas en poursuivant cette tradition.

Dans les symphonies chorales de Mahler, le texte reflète son idéal poétique dans le domaine métaphysique. Le texte de la 2ème symphonie constitue un amalgame de christianisme et de mythologie pangermanique.[21] Le dernier mouvement est une description dramatique de l’Apocalypse, qui sert de repoussoir au chœur sur la résurrection. Le texte est un mélange de la Bible et d’un texte de Mahler lui-même. Dans la 3ème symphonie, le texte de Mahler proclame une célébration “Nietzscho-Shopenhauerienne”de la volonté de vaincre la mort.[22] Le texte de la 8ème symphonie renferme des concepts théologiques tels que la grâce, l’amour et l’illumination. La première partie est une hymne latine du XVIIIè siècle; la deuxième est la 2ème du Faust de Goethe[23] Cette contradiction apparente sert juste à illustrer la solide culture littéraire de Mahler, et l’idée d’insérer un texte et un source supplémentaire pour rallier l’humanité à l’idée fixe spirituelle du compositeur. Il y a eu de multiples querelles au sujet des réelles intentions philosophiques de Mahler. Un clan défend le christianisme, tandis que l’autre hurle aux accents païens, voire au syncrétisme religieux.[24] Quel que soit le camp de sa musique (pour autant qu’elle en ait un), pour Mahler elle semble être un outil pour rechercher la vérité spirituelle, et donc le texte ne peut pas être ignoré dans ce débat.

- Aspects techniques de l’utilisation chorale

Mahler considérait la voix humaine comme une source sonore, un timbre distinct parmi les instruments d’orchestre. En parlant de la 8ème symphonie, il décrit comme suit la voix humaine : “Ici… les voix sont également employées comme instruments: le 1er mouvement est strictement symphonique par sa forme mais il est entièrement chanté… une symphonie ‘pure’ dans laquelle le plus bel instrument du monde trouve sa vraie place.”[25] Roman prétend que l’emploi de la voix humaine est un aspect de l’évolution musicale de Mahler, de l’accompagnement orchestral essentiellement homophone à la “poly-mélodicité” où la voix reçoit un rôle identique à celui des instruments, comme dans la 8ème symphonie.[26] Par exemple au 2ème mouvement mes. 102 de la 8ème, le passage monotone en accords des ténors et basses renforce le fond instrumental harmonique des contrebasses, harpe et harmonium, tandis que le matériau mélodique est distribué en contrepoint entre voix et instruments.[27]

Floros va plus loin, et prétend que puisque les thèmes sont également répartis entre les voix et les instruments, la musique peut aussi se découper sémantiquement comme le texte.[28] De plus, les thèmes vocaux sont “répartis instrumentalement dans le sens où ils sont répétés, transposés, variés, permutés, augmentés, combinés entre eux et apportant des couleurs nouvelles.”[29] Donc en fait, Mahler abordait la voix comme un instrument dans sa construction symphonique.

Même traitée comme un instrument, la voix a dans la musique de Mahler un rôle musical distinct. Primo, le timbre humain est employé pour réaliser les images poétiques évoquées par le texte. Par exemple, la répartition des timbres dans le Choral de la Résurrection de la 2ème symphonie suggère une musique approchant progressivement d’une distance lointaine, l’appel de l’ange aux corps des morts s’élevant de la poussière exactement comme dit dans l texte.[30] Un autre exemple est le 5ème mouvement de la 3ème symphonie, “Was mir die Engel erzählen” [Quand l’ange m’a dit], où le timbre est volontairement large, correspondant au concept de musique céleste.[31] Mahler confie ce mouvement aux voix de garçons alto solo, et aux voix de femmes dont quatre cloches accordées,[32]toutes au timbre clair et large pour renforcer l’idée textuelle du passage musical.

Le timbre aide aussi Mahler à illustrer des idées philosophiques comme l’illumination et la grâce, qui constituent le fondement de la 8ème symphonie. Flore suggère que, dans la coda, un des thèmes (Accende) est particulièrement mis en exergue parce qu’il est chanté par des garçons.[33]Mahler établit aussi une distinction entre les voix humaines. Par exemple dans la 2ème symphonie, il prend en considération les différences de timbre et de couleur quand il utilise les voix de femmes et de garçons. Les garçons chantent à l’unisson tandis que le chœur de femmes est richement distribué. De plus les passages rapides sont harmonisés à trois voix, tandis que les plus lents sont à quatre.[34] Cette distinction de timbres sert d’outil puissant pour l’exposé par Mahler des idées.

L’étendue et la tessiture sont d’autres aspects de la voix humaine que Mahler utilise, dans ce cas, en gardant à l’esprit les grands chanteurs de son temps et en exploitant son expérience de chef d’opéra.[35] L’étendue vocale utilisée dans ses œuvres est en effet vaste. Mahler étire les limites pratiques de l’usage habituel (de la 13ème majeure à 2 octaves).[36] Les étendues les plus extrêmes se trouvent dans la 2ème symphonie tandis que celles de la 8ème sont plus confortables, peut-être en raison des grandes masses chorales. En fait la tessiture tend vers l’extrême haut de l’étendue vocale.[37] Le registre médian (altos et ténors) est large et clair, idée issue de l’orchestration de Mahler où les voix sont étirées vers les limites de leur étendue.[38] La voix est le point de départ du son: cela peut s’étendre à toute la palette requise du chœur dans les symphonies de Mahler, et se matérialise aussi concrètement. Roman explique que dans les symphonies de Mahler les parties vocales sont traitées instrumentalement:

Ces parties et passages se caractérisent par un aspect global anguleux dont des sauts d’octave constants, par des intervalles et accords parallèles, et par diverses dispositions du genre du traditionnel “remplissage” de certains instruments d’orchestre.[39]

Il est à noter que l’écriture vocale de Beethoven dans sa 9ème symphonie, et son traitement des solistes vocaux comme des instruments, sont fortement influencés par les procédés de Mahler.[40] Si ce n’est pour les tessitures extrêmes, Mahler n’innove pas fondamentalement : il travaille toujours à l’intérieur des limites traditionnelles de l’usage vocal choral. Dans la 2ème symphonie, l’orchestre joue le rôle d’accompagnement homophone dans le mouvement choral. Dans la 3ème il y a un équilibre entre les passages orchestraux soutenus par les voix et ceux qui sont indépendants et polyphoniques. Au fond, dans la 8ème symphonie il y a entre l’accompagnement et l’orchestration contrapuntique une alternance, pas une séparation nette.[41]

Itest important de remarquer que même si à plusieurs endroits l’écriture chorale n’est pas idiomatiquement caractérisée par des sauts, la construction est généralement homophone; si la polyphonie apparaît dans les parties vocales, c’est comme instrument dramatique. Par exemple Roman explique cette exploitation dramatique de la polyphonie quand il relève que “les entrées en imitations du chœur à cinq voix de la 2ème symphonie, passant du ppp au ff en environ vingt mesures, participent à la réalisation d’un sommet dramatique englobant la coda chorale avec sa majestueuse respiration et sa puissance.”[42] Donc pour Mahler l’homophonie semble être la structure de base qui sous-tend les inflexions chorales, à l’exception du sommet dramatique que constitue son usage de la polyphonie.

La prédominance de l’homophonie en accords se justifie par le souhait mahlérien de l’intelligibilité textuelle. Et ici, qui dit texte dit poésie, aussi chère à Mahler que la musique ![43] Rien ne dépasse ses propres mots pour exprimer cette aspiration à rendre le texte aussi compréhensible qu’il puisse l’être: “Mes deux symphonies [la 2ème et la 3ème] recèlent des aspects intérieurs de toute ma vie, de la vérité et de la poésie en musique,”[44] et “dans ma symphonie [la 8ème], la voix humaine est, en fin de compte, la limite de toute la pensée poétique.”[45] Avec cela à l’esprit, deux procédés textuels en particulier abordés par Roman en vue de la clarté sont à mentionner ici: primo les passages choraux à l’unisson ou en octaves, pour accentuer le texte et accroître la variété textuelle, et secundo les passages en réponses utilisés comme intermèdes entre les passages choraux complets et partiels.[46] L’homophonie est donc le procédé textuel naturel à utiliser pour mettre en lumière le débit du texte dans les symphonies de Mahler.

Le traitement conventionnel du chœur reflète l’équilibre entre le chœur et l’orchestre, ainsi qu’entre les voix. Notez les instructions de Mahler dans le final de la 2ème symphonie, où les basses graves ont un Si bémol en dessous de la portée. Dans cet exemple précis, Roman prétend que, en dépit des considérations sur la faisabilité de ces parties de basses, Mahler avait un sens précis de l’équilibre, crucial pour l’effet de l’entrée initiale du chœur de la Résurrection:

Sous peine de rater l’effet voulu par le compositeur, les basses [ne doivent pas chanter] une octave plus haut : il n’est pas vraiment crucial que ces notes graves soient audibles. Cette notation [a pour but] d’éviter que les basses graves “préfèrent”, pour ainsi dire, le si bémol aigu, et donc le chantent plus fort.[47]

En outre, il y a rarement entre le chœur et l’orchestre des doublures au sens techniquement propre. En fait, excepté pour les sommets dramatiques le matériel est clair et peu abondant.[48] En fin de compte on peut le dire clairement : dans les mouvements choraux de ses symphonies, Mahler réalise l’équilibre entre les effectifs choral et instrumental.

- Conclusion

L’étude du trésor vocal de la musique de Mahler, particulièrement dans le domaine choral, mérite pour plusieurs raisons un sérieux intérêt. Primo, statistiquement la voix joue un rôle dans presque toutes les œuvres de Mahler. Secundo, comme chef d’opéra Mahler a eu l’occasion (et avait besoin) d’approfondir sa connaissance de la voix. Tertio, son affinité émotionnelle et sa familiarité avec la voix sont évidentes pour tout qui connaît ses œuvres vocales. Enfin, l’intérêt de Mahler pour la voix humaine ne se limite pas à une”période” mais se manifeste à travers tout son œuvre de compositeur. Malgré ces raisons, l’œuvre vocal de Mahler continue à faire l’objet de peu d’intérêt de la part des étudiants, avec une référence seulement marginale à cet aspect plutôt vaste de la musique du compositeur. Pour Roman, cela pourrait être dû au fait que Mahler n’a pas écrit d’œuvre isolée dans ce domaine.[49] Néanmoins, le chœur apparaît dans de nombreuses créations de grande ampleur telles que cycle vocal, cantate ou symphonie. Quoi qu’il en soit, la musique chorale de Mahler reste en attente de recherches scolaires, et il faut espérer que la matière de ma recherche aiguisera dans l’avenir l’intérêt des étudiants.

- Références

- Abbate, Elizabeth Teoli. Myth, Symbol, and Meaning in Mahler’s Early Symphonies. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1996.

- Alexander, Metcher F. Representative Nineteenth Century Choral Symphonies.

- M .M . thesis, North Texas State·University, 1971.

- Bauer-Lechner, Natalie. Recollections of Gustav Mahler, ed. Dika Newlin, trans.

- Peter Franklin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Blaukopf, Herta, ed. Gustav Mahler -Richard Strauss Correspondence, 1888-1911,

- trans. Edmund Jephcott. London: Faber and Faber, 1984.

- Blaukopf, Kurt, and Herta Blaukopf. Mahler: His Life, Work, and World, 2nd ed.

- London: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

- Franklin,Peter, “Mahler, Gustav,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. New York: Macmillan, 2001. XV,602-31.

- Franklin, Peter. Mahler: Symphony No.3. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991. (Cambridge Music Handbooks, ed. Julian Rushton, unnumbered volume)

- Floras, Constantin. Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1997.

- Holbrook, David. Gustav Mahler and the Courage to Be. London: Vision Press, 1975. (Studies in the Psychology of Culture, unnumbered volume)

- Johnson, Steven Philip. Thematic and Tonal Processes in Mahler’s Third

- Symphony. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1989.

- La Grange, Henry-Louis de. Mahler, Vol. I. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1973.

- La Grange, Henry-Louis de. Gustav Mahler, Vienna: Triumph and Disillusionment

- (1904-1907), Vol. III. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Lea, Henry A. Gustav Mahler: Man on the Margin. Bonn: Bouvier, 1985.

- Mahler, Alma. Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters, ed. Donald Mitchell, trans.

- Basil Creighton. London: Cox & Wyman, 1973.

- Mahler, Gustav. Mahler’s Unknown Letters, ed. Herta Blaukopf, trans. Richard Stokes. London: Victor Gollancz, 1986.

- Mitchell, Donald. Gustav Mahler: Songs and Symphonies of Life and Death,

- Vol. III. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Roman, Zoltan. “The Chorus in Mahler’s Music,” The Music Review XLIIl/1 (February 1982), 31-43.

Adamilson Guimarães de Abreu a obtenu à l’Université de Missouri-Columbia (USA) ses licences en Direction chorale (2004), en Études générales (2002) et de Spécialiste en Éducation musicale (2015). Comme chanteur professionnel, Mr Abreu a obtenu um contrat de deux ans au Teatro Municipal de São Paulo (1991-1992). Parmi ses distinctions, une 3èmeplace au 1°Concurso Nacional de Canto “Cidade de Araçatuba” (1996), et comme chef de chœur il a atteint la finale du 1° Concurso Nacional de Coros FUNARTE (1997) avec son chœur se plaçant parmi les six meilleurs du pays. Mr Abreu s’intéresse à la recherche dans les domaines de la direction et de l’éducation musicale, en particulier à l’exploitation du chant choral et de la direction comme outils pédagogiques pour enseigner l’éducation musicale générale. Dernièrement Mr Abreu a jugé des concours vocaux tels que le concours SESI II Festival da Canção à Brasilia (Brésil) et s’est impliqué comme chef de chœur pour l’opéra Romeo et Juliettede Gounod et La Traviata de Verdi lors des IIIè et IVè Festivals Internacionales de Ópera da Amazônia. Pour l’instant Mr Abreu est professeur à temps plein à l’Universidade Federal do Pará, à Belém (Brésil). Email: abreu_2004@yahoo.com

Edited by Steve Lansford, US

Traduit de l’anglais par Jean PAYON (Belgique)

[1] Zoltan Roman, “The Chorus in Mahler’s Music,” The Music Review XLIII/1(February, 1982), 32.

[2] Dans”MahlerJuvenilia,”ChordandDiscord,III/1(1969),68,JackDiether interprète comme suit la dernière ligne du texte de Mahler : “Si je ne peux pas trouver de sens à ma vie je suis bouleversé, ne trouvant face à moi que le néant“.

[3] Dans l’argument de la 2èmesymphonie,Mahler énonce clairement ses préoccupations quant aux questions de la vie et de la mort, en l’occurrence une vision plutôt optimiste puisqu’elle culmine par la résurrection ; cf. Donald Mitchell, Gustav Mahler : The Wunderhorn Years, Vol. II (University of California Press, 1995), 183.

[4] ConstantinFloros, Gustav Mahler: The Symphoníes (Portland: Amadeus Press, 1997), 54.

[5] David Holbrook, Gustav Mahler and the Courage to Be (London: Vision Press, 1975), 12.

[6] Cf. Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Wíll and Idea (London : Routledge and Kegan , 1957).

[7] Cf. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy and the Case of Wagner (New York: Vintage Books, 1967).

[8] David Holbrook, The Courage to Be, 8 (fournit des informations sur la démarche de Wagner)

[9] Steven Philip Johnson, Thematic and Tonal Process in Mahler’ s Third Symphony, (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1989), 9.

[10] ConstantinFloros,TheSymphonies,226.

[11] AlmaMahler,GustavMahler:MemoriesandLetters(London:Cox&Wyman, 1973),103.

[12] Peter Franklin, “Mahler, Gustav,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie, (New York: Macmillan, 2001) XV, 615.

[13] Alma Mahler, Memories and Letters, 101.

[14] Peter Franklin, Mahler: Symphony No. 3 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 37.

[15] Henry A. Lea, Gustav Mahler: Man on the Margin(Bonn: Bouvier, 1985), 49.

[16] Henry Lea, Man on the Margin, 96.

[17] Ibid,100.

[18] Constantin Floros, The Symphonies, 104.

[19] Elizabeth Abbate, Myth, Symbol, and Meaning in Mahler’s Early Symphonies (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1996), 189.

[20] Elizabeth Abbate, Myth, Symbol, and Meaning in Mahler’s Early Symphonies (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1996), 191.

[21] Précisément l’“Edda”, mythe nordique comportant une évocation de la fin du monde. Heimdal, né de l’union d’Odin avec neuf géantes en même temps, est désigné comme gardien du pont arc-en-ciel, qui relie la terre au ciel. Au son de sa trompette, il appelle toutes les créatures à combattre ses ennemis, et sa dernière sonnerie annonce le début de la lutte finale. Certains de ces éléments se retrouvent dans la musique de Mahler. (Cf. Abbate, Myth, Symbol, and Meaning, 90-91).

[22] Elizabeth Abbate, Myth, Symbol, and Meaning, 72. D’autres auteurs partagent ce point de vue tandis que Floros le rejette, adoptant plutôt le concept de volonté chez Schopenhauer. Pour Abbate, les intentions musicales optimistes de Mahler et le contenu intellectuel de la 3ème symphonie s’opposent à la conception cynique du monde qu’a Nietsche.

[23] Pour une étude approfondie du texte, voir Donald Mitchell, Gustav Mahler: Songs and Symphonies of Lífe and Death, Vol. III (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985).

[24] Les auteurs qui défendent ces idées sont, respectivement, Donald Mitchell et HenryA.Lea,HertaBlaukopfandNatalieBauer-Lechner,Constantin Floros et ElizabethAbbate.

[25] Donald Mitchell, Symphonies of Life and Death, 519.

[26] Zoltan Roman, “The Chorus in Mahler’s Music,” 39.

[27] Ibid., 39.

[28] Constantin Floras, The Symphonies, 68.

[29] Constantin Floros, The Symphonies, 223.

[30] Constantin Floros, The Symphonies, 77.

[31] Le texte de cette section est le poème ArmerKinderBettlerlied(“Chant de mendicité des pauvres enfants”). Il évoque le”doux chant des anges“ et la “joie céleste sans fin”, l’histoire du reniement de Pierre et de son pardon obtenu via Jésus (see Ibíd.,104).

[32] Ibid., 104.

[33] Constantin Floros, The Symphonies, 226.

[34] Metcher Alexander, Representatíve Nineteenth Century Choral Symphonies (M.M.thesis, North Texas State University, 1971), 176.

[35] Metcher Alexander, Representatíve Nineteenth Century Choral Symphonies (M .M . thesis, North Texas State University, 1971), 148.

[36] Ibíd., 189.

[37] Une exception est la tessiture des garçons, dont Alexander prétend qu’elle ne manque jamais de ressortir vu sa sonorité propre de sa texture musicale (cf. Metcher Alexander19th Century ChoralSymphonies,189).

[38] Toute cette information se trouve détaillée dans l’article de Roman, avec des tableaux de statistiques comparatives de participation et d’étendue vocales dans toutes les symphonies chorales et Das Klagende Lied.

[39] Zoltan Roman, “The Chorus in Mahler’s Music,” 39.

[40] Lors du climax de la 9ème symphonie, la tessiture surprenante des solos de ténor et d’alto compromet la qualité de l’intonation et l’équilibre du quatuor vocal avec la sonorité massive de l’orchestre. Leur rôle est de remplir l’harmonie, technique utilisée plus tard par Mahler dans ses symphonies.

[41] Zoltan Roman, “The Chorus in Mahler’s Music,” 40.

[42] Ibíd., 41.

[43] Herta Blaukopf et Kurt Blaukopf in Mahler: Hís Life, Work, and World (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991), 31, relèvent que Mahler démontrait un égal talent pour la musique et la littérature.

[44] Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Recollectíons of Gustav Mahler, ed. Dika Newlin, trans. Peter Franklin (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1980), 75.

[45] Mitchell, Symphoníes of Life and Death, 519.

[46] Ibíd., 41.

[47] Donald Mitchell, Symphonies of Life and Death, 38.

[48] Zoltan Roman, “The Chorus in Mahler’s Music,” 42.

[49] Ibíd., 31.