Music Therapy and African Music

Ambroise Kua-Nzambi Toko, Democratic Republic of Congo

Ambroise Kua-Nzambi Toko, Democratic Republic of Congo

Choir conductor

TRADITIONAL AFRICAN MEDICINE

The Odyssey of This Ancestral Practice

Established well before the arrival of scientific Western medicine, traditional African medicine has proven itself since the dawn of time. Practised more frequently in rural areas, it has often attracted many people, especially in areas where modern health centres are rare, and is naturally turned to as an inevitable alternative for certain ailments for which modern medicine seems to be powerless (3).

Even in modern times, traditional African medicine has always been a grassroots reality. Native care constitutes the first line of treatment for persons whose ailments are of seemingly inexplicable or mysterious origin.

Traditional medicine is used by about 80% of populations, according to the World Health Oganization (WHO), but unfortunately, it continues to be neglected and fought against and is generally unsupported and without funding.

In the popular imagination of African Bantus, healing is to be found in nature, in the physical and spiritual world (cosmic, ancestral, mystical). They believe in the healing power of rites, as well as in the power of nature contained in:

- sand, stone, water, fire, air

- salt, oil, powders

- plants, leaves, tree bark, roots, fruit

- heat, cold, wind

- rain, sun, the moon

- light, odours, animals

- images, masks, statues, totems

- words, sounds, cries, music, chant, prayer

- dance, trance, the rhythm of percussion instruments

The Healers – Initiated and Uninitiated

Usually, healers come by their powers through heredity, with healing gifts passed down from grandfather to great-grandson but herbalists, who are laymen in the spiritual sense, study plants and their curative virtues as well as studying symptoms and side effects.

Among the healers one can find the chosen ones, heirs of the tradition, the initiated, those who have been trained and, of course, many charlatans who have paid their way to power and who sell illusions, as well as those who practise the profession by imitation.

The healers are either real gurus surrounded by aides or persons working alone sometimes with the assistance of initiated helpers or caregivers. They may go by the name: Healer, Fetishist, Trad-practitioners, Trad-therapists, Seers, Clairvoyants, Sorcerers, Prophets, Diviners, Inspired Spokesperson, Clan Chiefs (among the Ne kongo, they are called Nsadisi, Nganga-Nkisi, Ngunza, Mbikudi, Ma ndona, Ndoki, Mpovi, Mfumu a kanda…).

From Its Strength to Its Weakness

A practice strongly linked to spiritual beliefs and deeply rooted in an ancestral culture, traditional African medicine continues to claim to offer a panacea to all ills. However, that some of its weaknesses can lead to often unpredictable multiple consequences is no secret to anyone and this has not escaped the collective consciousness. The basis of these inadequacies are due to several reasons, including:

- The fact that knowlege is transmitted orally;

- The lack of documentation summarizing knowledge;

- The absence of a framework for collective or scientific reflecton;

- Therapeutic methods which are generally less elaborated and defined;

- The very select and even egotistical system of recruitment for training;

- The low degree of assurance with regard to the precision of dosage for the medicines used and the treatments administered. The risk of going too far or overdosing are real.

- Its very subjective and even esoteric nature, over which only the initiated have the monopoly, which often leads to the irrational.

ILLNESSES AS SEEN BY AFRICAN HEALERS AND TRAD-THERAPISTS

The ailments and pathologies treated by traditional medicine are many and varied. Such is the case with the types of treaments which can vary from one tribe, ethnic group or people to another.

For example, the ailments treated might include mental illness, psychic troubles, illnesses of a mystic nature, the mysterious loss of certain senses (sight, hearing, memory), sexual impotence, loss of virility, feminine sterility and many more.

Certain illnesses are better treated in some tribes using different therapeutic methods.

Among these ailments we find those whose diagnosis and treatment are done by procedures of a spiritual nature, thereby calling upon divination, incantations, invoking ancestors (bankulu) or spirits (Mpeve), as well as invoking God, the Supreme Being, the Creator, the Indestructible (Akongo, Nzambi a mpundu among the Ne Kongo, Nzakomba among the Mongo, Mvidi mukulu among the Luba, Wonia Shongo among the Otetela, Imana among the ethnic groups of Rwanda and burundi,…).

This would be linked to the belief that certain illnesses are caused by bad spells, curses, family ties, being possesses, attacks by sorcerors, the settling of accounts through festishist methods or due to the negative consequences of crimes committed by the guilty party.

In Black African civilization, one can fall ill by offending God, spirits, ancestors, nature, society or going against the sacred principles of community life, says Cameroon Professor Bingono Bingono, a specialist in crypto-communication. Thus, one treats the body through the spirit.

The healing process may require sessions that take several hours, several days or even several weeks in a specific location. This is often due to or related to the severity of the ailment to be treated as well as to the rituals inspired or dictated by the spirits. It is most often women and children who request these treatments.

Depending on the type of illness, the patients are either housed in the antechambers of the healers (Ngunza, Ma Ndona, Nganga Nkisi…), or they may simply go for the duration of the healing session. Others may be taken to specific sites (into the bush, under a tree, at the edge of a river…).

MUSIC IN ANCESTRAL PRACTICES

Healing is not really directly related to music, chant, dance or trances, otherwise chant, for example, would be prescribed for healing, and this panacea would be among the most popularly used grandmothers’ remedies. In addition, this would quickly have allowed the development of African music therapy.

Various sources, however, contend that certain chants have a healing power when they are intoned by initiated practitioners. There is a practice which consists of asking the initiated to compose a chant or a hymn that can offer therapeutic support during the healing rites. Such is the case among the Luba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) when it comes to the “Lufu”, which means death. Hymns are composed to be sung during the ritual to help the patient escape death. Music, chant, percussion, dance and trance are often integrated into most of these rites.

While in his thesis on “the relationship of music and trance” Gilbert Rouget demonstrates that neither the melody, the rhythm, chant nor instrumental music provokes a trance to the point of naturally healing the illnesses (2) and in his thesis entitled Music and Trance in Afro-American Religions Erwan Dianteill strongly affirms it, it can be observed that numerous healers enter into a trance through chant and the rhythm of the percussion. Chant is associated with prayer, and dance can lead to a trance and prayer.

Despite the great variety to be found, different types of traditional African music present certain common characteristics. In general, the music is circumstantial, functional, ritualistic, contextual and therefore utilitarian. The omnipresence of these characteristics in different types of rituals reveals the African concept of music as being more than just a simple means of communication among humans.

Music can be evocative, it can help release emotions which may be suppressed, and it can help transport someone towards a world of plenitude and well-being. There is music of a mystic nature which can call upon the intervention of supernatural or mystic forces, music which can be object-oriented, incantation music, meditative music which can provoke positive feelings, music for relaxation and music for healing and self-healing.

The word “music” itself is difficult to translate in many African languages. It is for this reason that chant, or song, and music are often translated by using the same word. In Kikongo, the language spoken in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Angola, Nkunga means singing but also music. Singing or chant thus plays an avant-garde role. Where words stop, singing begins.

As a support for communication, il fundamentally has two dimensions. It can belong to the sphere of pheno-communication, which is essentially material, tangible, physical and acoustical, being part of the physical and material work. But music can also be considered a form of crypto- or hidden communication, which can be mystical, esoteric or spiritual, contends Professor Bingono Bingono.(4)

The average person does not naturally enter into the crypto-communicative dimension of singing or chant, but in certain conditions and often during rituals, one can enter into this dimension through pheno-communication.

Chant, instruments and dance mix easily in a number of situations, where by tradition or by nature, one could not completely eliminate music. Singing is therefore one of the components of rituals dedicated to healing illnesses. The vocal sonorities and styles can vary considerably from one geographic location to another.

Chant and Healing

Is healing through music possible? Is native healing through sound possible? Does music for healing exist?

In several African traditions, singing or chant, as well as dance leading to trance, have a therapeutic function beyond their artistic value. In addition to chants on different themes, there are indeed those which are used in healing practices for certain illnesses. All illnesses are considered to be a malfunction of the body, biological functions, the mind, the psyche or the spirit. Chant can also lead to a modified state of being allowing growth of human capacity. Therefore, it is a component of healing rites because of the approach of the treatment that is planned.

In general, African traditions recognize the power of music, not as a real or concrete force or as constituting a principle asset, but rather as an accompanying support. It is an additional support through which mediator can help establish a connection between the interior and the exterior to reach higher spheres, and to also set the stage for a better bonding of the two.

In the therapeutic approach to illnesses, anointment is critical. The initiated responsible for anointing are assisting the healer, himself anointed, who passes on the responibility to them. Their role is to sing, dance and play traditional instruments.

As is the case with the very large range of plants, where often one plant along can help heal several illnesses, music is also considered to be endowed with a certain curative power.

Healing Rites

Music, chant and dance are associated with the native healing systems in many sub-Saharan tribes and ethnic groups of Africa. The diviner-healers often use the divinatory arts to detect illnesses and especially their origins. Clairvoyants can detect the illness by entering into contact with the patient. In some rites, chant is associated with dance, with the trance sometimes accompanied by traditional musical instruments, each of which has a specific function. The chants are intoned either by the trad-therapists or by their assistants and, in some cases, even by the patients themselves during one or more phases of the ritual. Some chants are intoned as hymns, as a prologue and others are used to create a placebo effect predisposing patients to develop their faith and thus participate in their own healing.

Healing rites are common among the African Bantu and have several points in common. Banned by Christian missionaries and by current Christian religions, these ancestral practices have disappeared except for a few which have managed to resist the pressure. Some chants have been recovered, adapted and integrated into the repertoire of traditional groups.

In the DRC, the Zebola among the Mongos is a rite which calls upon chant and dance to chase away spirits. The possessed patient, often a young woman, enters into a convulsive trance and/or loses consciousness. Chant, music and percussion are also used in the Nkanda circumcision rites of the Ne Kongo and in the Gaza rite among the Bangala or the Bamongos. Percussion instruments are used by the healers or their initiated assistants, each one having a specific function.

Among the Mbata (Bambata), patients suffering from Ntulu nwengina (asthma attacks) arrive with live roosters as well as other gifts singing “Nsusu a koko”:

Among the Bamaniangas, singing is part of the Kimoko rite.

For example, the chant lulendo lwa satana diata lo

which means “to neutralize the power of Satan”.

There is also the Mayititi rite where chant is used to heal Mayititi (mumps).

In this ritual, the patient places his or her head in a hole dug in the surface of the ground and sings this chant :

Yi yi yi mayititi

Meka kana sala mu

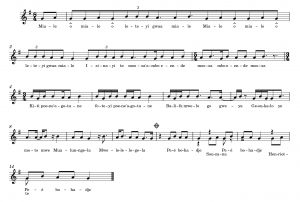

Miale O – Healing chant of the Topoke people

rubato

In the Republic of Congo (Congo-Brazzaville), the Lemba, Mudiri, Tingigila healing rites also make use of chant.

The UNESCO-protected Vimbuza is a healing dance popular among the Tumbuka people, an ethnic group in northern Malawi. It is similar to a popular dance among the Ba Maniangas in the DRC. This similirity can also be found in the rhythm of the Ngoma drums.

Singing is also present in the Bissima rite of the Ekang tribe in Cameroon.

Paradigm of Ritual Chants

Navigating the continuum between subjectivity and objectivity, healing chants include incantations, praise and sung poems that may be repeated as mantras.

Certain characteristics, listed below, seem to be common to all of them:

- The compatibility linked to the essential or quintessential content;

- The coherence with the atmosphere of each phase of the ritual (adapting chants as soft invocations, murmurs, cries, authoritative declarations, declarations of healing or victory…). This may depend on the character of the chant and its literary content;

- Known chants of pure inspiration, required for a phase of the ritual;

- Intuitive or inspired chants, improvised by the healing trad-therapist or crypto-communicator or by their aides who are deep in a transfigured and transformed or modified state (a trance of creative inspiration, a divine trance);

- Chants having supposedly curative and calming virtues;

- Sung prayers and declarations;

- Evocative chants which can lead to a modified state (chants to go into a trance, chants to open the spirit, to chase away fears or doubts…

CHANTS IN SESSIONS OF PRAYERS FOR DELIVERANCE AND MIRACLE-HEALING

Having been fought against by Christian missionaries, many rites and chants have disappeared. The emergence and proliferation of so-called awake or post-missionary churches have opened another door, offering an alternative to these ancestral rites through prayer and miracle-healing sessions. Pastors, Evangelists and Prophets of God, anointed and endowed with a spiritual gift for miracle-healing having taken the place of trad-therapists, diviner-healers and others who organize special sessions, either in public during crusades and evangelization campaigns or in private prayer cells. These sessions are accompanied by songs of adoration, praise, supplication, declarations of victory over the enemy, darkness, demons, possessive spirits, as well as by diverse statements of faith and proclamations of healing in general. The name of Jesus Christ is at the centre of these christocentric sessions of religious exorcism and the results are surprising and real. Some patients heal at the very moment these chants are intoned. The success of this practice has moved many healers and trad-therapists to disguise themselves as prophets of God and entice crowds to follow them.

Examples of chants intoned during sessions of deliverance and miracle-healing:

- Yesu azali awa (Jesus is among us)

Kitisa nguya na yo (Manifest your power in this place) - Nguya, Nkembo na lobiko epayi na Yawe (power, glory and honour unto our God)

- Elonga ejali na makila ma Yesu (victory is in the blood of Jesus)

Imported Songs – Gospel Hymns

- I am the Lord that healeth thee

I am the God that Healeth thee, I am the Lord Your healer

I sent My word and I healed your disease, I am the Lord Your healer

You are the God that Healeth me, You are the God my healer

You sent the word and you healed my disease, You are the Lord my healer - He touched me

Shackled by a heavy burden,

‘Neath a load of guilt and shame.

Then the hand of Jesus touched me,

And now I am no longer the same.

He touched me, Oh He touched me,

And oh the joy that floods my soul!

Something happened and now I know,

He touched me and made me whole.

Dr. Ambroise KUA-NZAMBI TOKO is a researcher and Director of the African Academy of Choral Music in DRC; a Member of ACJ International Council and the World Choir Games Council, as well as the Founder and Artistic Director of many choral festivals in DRC. He has studied musical arts, physics, computing, and choral conducting in A Cœur Joie International high-level workshops. Conductor of three Congolese choirs (Chœur La Grâce, Schola Cantorum AKTO – a Youth Choir and Chœur d’hommes du Centenaire, a male Choir), he is one of the most renowned Congolese composers and conductors. First Conductor of the African Youth Choir (2012-2015), he has conducted more than 130 international workshops, sessions and master classes on African and Congolese choral music. He has directed more than 300 international performances and has participated at more than 38 International choral Festivals with Chœur la Grâce. Best choral activist and conductor of the 50th anniversary of DR Congo (1960-2010) according to the Wallonie-Bruxelles Delegation of DRC (2010), winner of the prize “Special commendation” by the International Music Council in 2010, he has also earned four African choral music trophies. In July 2014, he received the National prize from the Minister of culture and arts of the Congolese Government and the trophy “Optimum Kantor” in November 2017 at Brazza (Congo). Author of three books: Mélopées sacrées, le papyrus de l’artiste; La voix décryptée, Musiques africaines – généralités et singularités, and several articles on choral music (ICB of IFCM, Chanter of ACJ Québec, Tuimbe of ACCM, …), he has also invented a new music notation system (Mimin’si). He received 2 doctorate diplomas Honoris causa (music art and hymnology) from the Triune Biblical University of USA, CANADA.

Dr. Ambroise KUA-NZAMBI TOKO is a researcher and Director of the African Academy of Choral Music in DRC; a Member of ACJ International Council and the World Choir Games Council, as well as the Founder and Artistic Director of many choral festivals in DRC. He has studied musical arts, physics, computing, and choral conducting in A Cœur Joie International high-level workshops. Conductor of three Congolese choirs (Chœur La Grâce, Schola Cantorum AKTO – a Youth Choir and Chœur d’hommes du Centenaire, a male Choir), he is one of the most renowned Congolese composers and conductors. First Conductor of the African Youth Choir (2012-2015), he has conducted more than 130 international workshops, sessions and master classes on African and Congolese choral music. He has directed more than 300 international performances and has participated at more than 38 International choral Festivals with Chœur la Grâce. Best choral activist and conductor of the 50th anniversary of DR Congo (1960-2010) according to the Wallonie-Bruxelles Delegation of DRC (2010), winner of the prize “Special commendation” by the International Music Council in 2010, he has also earned four African choral music trophies. In July 2014, he received the National prize from the Minister of culture and arts of the Congolese Government and the trophy “Optimum Kantor” in November 2017 at Brazza (Congo). Author of three books: Mélopées sacrées, le papyrus de l’artiste; La voix décryptée, Musiques africaines – généralités et singularités, and several articles on choral music (ICB of IFCM, Chanter of ACJ Québec, Tuimbe of ACCM, …), he has also invented a new music notation system (Mimin’si). He received 2 doctorate diplomas Honoris causa (music art and hymnology) from the Triune Biblical University of USA, CANADA.

REFERENCES

- Oriane Marck, La musique dans la société traditionnelle au royaume Kongo (XVe-XIXe siècle) (Music in traditional society in the kingdom of Kongo, 15th to 19th c.), Master’s thesis, Université Pierre-Mendes, Grenoble, 2011

- https://journals.openedition.org/ethnomusicologie/114

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%A9decine_traditionnelle_africaine

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lu7rV-IlEy4

- https://www.musicinafrica.net/fr/magazine/la-musique-traditionnelle-en-namibie

- https://ich.unesco.org/fr/RL/le-vimbuza-danse-de-guerison-00158

Consultants

- Ne Nkamu Luyindula, Ethno-musicologist, Director of the Centre Mbongi Eto, Ne kongo

- Souzy Lituambela Lolea, choir director and chorister, Chœur la Grâce, member of the Topoké tribe

- Bijou Massamba, choir director and chorister, Chœur la Grâce, member of the Mongo tribe

- Laurentine Makayisa Londa, eyewitness

- Olivier Kanda Nzuzi, choir director, eyewitness

- Charles Mathongo Damas, chorister, Chœur d’hommes du centenaire, eyewitness

- Lily Abessolo, chorister, African Youth Choir (2013-2015), Cameroun

- Rodrigue Atsou, choir director, Pointe-Noire, Congo-Brazza.

- Michée Kanda, choir director, transcription

Translated by Patricia Abbott, Canada