2021 centenary of two Argentine composers Astor Piazzolla and Ariel Ramírez

Oscar Escalada, conductor, Argentina

1921 was a significant year in my life, as it was the birth year of three influential people who, in the course of their lives, made a strong impression on my profession as a musician: my mother, Astor Piazzolla and Ariel Ramírez.

Of my mother, I can say it was she who supported me in the critical moment of decision between medicine and music.

Piazzolla, in particular, has been influential in that my contact with the academic world was largely through him. We also share the same record production company and some television programs.

As for Ariel Ramírez, my initial introduction was through singing his Misa Criolla, followed by later years in which, on repeated occasions, I conducted the piece with him at the piano.

Piazzolla was born in Mar del Plata on March 11, and while he was still a child, his parents emigrated to the United States where they settled in Brooklyn.

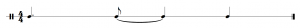

This fact is not insignificant because his characteristic rhythmic style following the 3+3+2 formula (Fig. 1) emerged as a result of the influence of a childhood friend from a Jewish family who lived in the same building. Both families held shared gatherings in their homes where the young Astor heard that same rhythm.

Ramírez was born in the City of Santa Fe on the 4th of September of the same year.

Like Piazzolla, he experienced events outside his country that had a definitive influence on his compositions.

While traveling through Germany, he met two nuns at the Mariannhill Convent in the city of Würzburg where he stayed. Both told him that a nearby house operated as a concentration camp where those detained would be sent to their deaths.

The nuns had found a hole under the surrounding defenses where, each night, they left a package with food that disappeared the next morning. They did this every night until the year in which they found it untouched.

The episode had a great impact on Ariel’s spirit and sowed in him the desire to compose a religious piece in tribute to these nuns who had risked their lives to help people they never met.

With the advent of the Second Vatican Council, great changes have taken place in the Catholic Church, including the use of the local language in liturgical song.

Ramírez’s college classmate in Santa Fe, who became Bishop Catena, suggested that he compose a mass in Spanish. Ariel was inspired and finally wrote the piece, basing it on his deep interest in telluric influences, which led him to use musical forms with roots in folklore.

The Misa Criolla was dedicated to the Mariannhill nuns, Sisters Elizabeth and Regina Brückner.

It is interesting to see how both composers drew on their musical traditions as a basis for the subsequent development of their works. In Ramírez’s case, the Bishop was key, and in Piazzolla’s, Nadia Boulanger.

The connection between the composers’ works and choral singing, however, is not an outcome of their own efforts. In the Misa Criolla, R. P. Segade was responsible for realizing the choral version, and those of Piazzolla’s works also belong to third party arrangements, except in the case of the opera, Maria de Buenos Aires.

Both composers created comprehensive, fully developed works wherein Ramírez, in addition to the Misa Criolla, composed Navidad Nuestra, Los Caudillos and Mujeres Argentinas, which includes the world-famous Alfonsina y el Mar.

For his part, Piazzolla was inspired by Antonio Vivaldi to compose the Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas, a group of four tangos for each season with the addition of the term “Porteño”(1). He also composed La Serie del Ángel and the aforementioned opera, María de Buenos Aires.

There are differences between the compositional techniques of each composer. In the case of Piazzolla, being a student of Alberto Ginastera and also obtaining his scholarship for study with Nadia Boulanger endowed him with an excellent facility with the orchestra, acquired through the former, and great compositional training via the latter.

Nadia was, by Piazzolla’s own definition, the most important woman in his life, second only to his mother, in that Boulanger provided him with the impetus to make his own music against all adversity.

And, oh, how he did! Tango traditionalists believed he had destroyed tango.

To the contrary. In my opinion, what he did was ground his work in the most traditional aspects of tango while giving the form wings to fly without limits. He did not deprive himself of the use of the sonata form or fugues or of expanding it harmonically, or of adding improvisations and even doing a 3/4 tango.

I believe that his Libertango is a dramatization of what I’ve mentioned above. In the first place, it is noteworthy that, as a name, he used two words that represent topics of the highest value for him: freedom and tango. Hence, Libertango.(2)

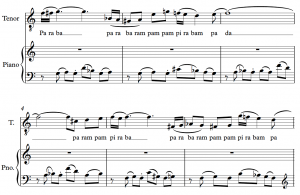

It is a very interesting composition based on a consistent ostinato (Fig. 2) that remains present throughout the work, sometimes complete, sometimes segmented, but always active.

I feel a sense of freedom when it reaches the bridge. (Fig. 3) I don’t believe he used the ostinato for its own sake. Rather, I believe that he was looking for a way to express his ability to emerge victorious over a disparaging reiteration, one that tethered him to a tradition seeking its own path of development. And when he found it, he produced that marvelously liberating profusion that, while still preserving traditional roots, enriched them without discarding them.

Ramírez is more measured in his creation because, although he had the virtue of generating comprehensive works in the field of Argentine folklore, the internal structure offers beautiful melodies and a broader harmony with great beauty and, in some cases, engages in a nonobservance of form for the benefit of the text. But he maintains full control of the work. He adds no improvisations, nor are his harmonies that disruptive.

For example, the Credo declares that it is a “truncated chacarera”. In fact, it is not, neither due to its form nor because of its distribution of accents (3).

Of course, he could never have stayed with the chacarera form because the long text of the Credo would not have allowed it.

But the use of the chacarera’s lively rhythm is very apt for the expression of the Credo. An interesting detail is that the work is in the minor mode but changes to major at the moment in which the text talks about the resurrection of Christ. This type of logogenesis (4) has been used by other composers, but it is remarkable that it has served him in fulfilling his purpose of “Mettere il testo in musica” [put the text to music] as Zarlino used to say. (5)

In the Gloria, he suitably alternates between the carnavalito (Fig. 4), which is a free dance in binary form, and a slower yaraví (Fig 5), a sweet and melancholic song from the Andean highlands. The work uses an introduction with a charango – a small chordophone from the altiplano – the melody of which will be reused in the yaraví by the choir a bocca chiusa, perhaps representing the winds of that plain surrounded by mountains.

The choice of both musical varieties is very successful since the carnavalito is a happy dance appropriate to the text, “Glory to God in the highest…”, etc., and the slow yaraví appropriate to the introspective song of “Lord and only son, Jesus Christ …”, etc.

Astor Piazzolla wrote works for the orchestra, such as the Concierto for bandoneón, and more than 30 orchestral arrangements. He also wrote for various groups and for tango orchestras for his most cherished tango, Adiós Nonino, dedicated to his father who, as Piazzolla was told while on tour in New York, had passed away.

But his volume of production is enormous, reportedly more than 2000 compositions and innumerable arrangements for each of them.

Also prolific was Ariél Ramírez, who was President of SADAIC, the Argentine Society of Music Authors and Composers, as well. Although his work was more intimate, always linked to telluric rhythms, he has made very important contributions. Of these, I highlight his production of comprehensive and extensive works because, until his arrival, folklore was limited to brief works, characteristic of the style.

Astor Piazzolla passed away on July 4, 1992, and Ariel Ramírez on February 18, 2010.

Thank you Astor and thank you Ariel for having been able to enter that so-exquisite world from which moments of beauty and emotion can be offered to the delight of your fellows.

(1) Inhabitants of Buenos Aires

(2) The attached examples are from the arrangement I made for SATB with the permission of Neil. A Kjos, Music Publishers, and of the Gloria by Warner/Chappel Argentina.

(3) The chacarera is a choreographed dance. If it does not maintain the form, it cannot be danced. It is truncated when the rhythm concludes on the third beat of the 3/4 time signature.

(4) Logogenesis comes from the Greek: logos – word – and genan – give birth, origin. It is the relationship of the text to the music.

(5) Gioseffo Zarlino, Italian composer, music theorist of the Renaissance.

Oscar Escalada is a teacher, composer, conductor, writer and editor of choral music. He is also President of the Argentine Association for Choral Music “America Cantat” (AAMCANT), a former member of the Board of Directors of the IFCM and a member of the Argentine Federal Organization of Choral Activities (OFADAC). He has given lectures for such events as ACDA conventions, IFCM symposiums and Europa Cantat as well as given workshops and seminars and adjudicated throughout the Americas, Europe and Asia. Escalada is the founder of the Children’s Choir of the Opera House of Buenos Aires, the Coral del Nuevo Mundo, the Seminar of the Conservatory of La Plata and the Youth Choir at the University of La Plata. The Argentine Senate awarded him for his work in the choral world and for his essay “Music and National Identity”. He leads the Latin American Choral Music series at the Neil A. Kjos Music Company in California, and he is an honorary member of the Associazione Naziolale Direttori di Coro Italiani. Email: escalada@isis.unlp.edu.ar

Oscar Escalada is a teacher, composer, conductor, writer and editor of choral music. He is also President of the Argentine Association for Choral Music “America Cantat” (AAMCANT), a former member of the Board of Directors of the IFCM and a member of the Argentine Federal Organization of Choral Activities (OFADAC). He has given lectures for such events as ACDA conventions, IFCM symposiums and Europa Cantat as well as given workshops and seminars and adjudicated throughout the Americas, Europe and Asia. Escalada is the founder of the Children’s Choir of the Opera House of Buenos Aires, the Coral del Nuevo Mundo, the Seminar of the Conservatory of La Plata and the Youth Choir at the University of La Plata. The Argentine Senate awarded him for his work in the choral world and for his essay “Music and National Identity”. He leads the Latin American Choral Music series at the Neil A. Kjos Music Company in California, and he is an honorary member of the Associazione Naziolale Direttori di Coro Italiani. Email: escalada@isis.unlp.edu.ar

Translated by Joel Hageman, USA

Head photo: 2009 World Youth Choir’s Argentinian singers © Marianne Grimont for Namurimage