Chevé from 19th Century Europe to 21st Century China

Lei Ray Yu, conductor and church musician

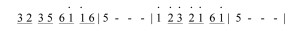

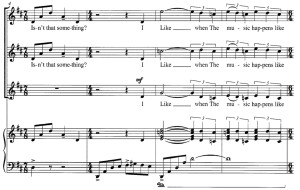

In China, an amateur choral singer’s music for “Jasmine Flower” is most likely to be notated as in fig. 1 and a SATB choral score would look like in fig. 2. While the most standard musical notational system in the world is the 5-line-staff system, the Chinese amateur choral world still utilizes a numeral system called Chevé. The Chevé, a pedagogical system, was first developed in France[1]. According to George W. Bullen, this system was designed to help students to “vocalize” music “at first sight without assistance of any kind from an instrument” (Bullen 1878). From the discussions in the correspondence section of The Musical Times throughout 1882, one can conclude that the Chevé system was adopted in some London elementary schools with much dissension. However controversial this method was, some young Chinese scholars took it back to China during the first part of the 20th century. Since the system “offers the easiest, best, and most natural system of learning to sing at sight”[2], it became quite popular during the war-time in China when the propaganda machine needed to rush anti-war music out to the public. Bullen stated in his article that “one of the difficulties for music educators is due to the lack of sound elementary knowledge on the part of their pupils” (Bullen 1878). As one of my amateur singers once said to me, “I know the bottom line is E on a treble clef, but what does it mean?” Ellerton explained in her letter that the numbers used in this system “express exactly the place of the notes in the Diatonic Scale” (Ellerton 1882); therefore, a person who is familiar with the diatonic scale would be able to easily translate the notes into sound.

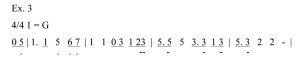

The following example (fig. 3) compares the staff notation with the Chevé system. The music is in G major, therefore “1”, which is the movable “do” in solfége, would equal “G”[3]. The Chevé is not the only pedagogical tool that utilizes the scale degree and solfége to begin teaching sight singing; the Kodály method and the Tonic Sol-fa notation in Brittan are both similar in nature. And all these systems were educational methods that were not meant to replace staff notation, but to eventually transition into staff notation. In China, however, for complex reasons, the Chevé never accomplished its purpose of helping students to read staff notation.

I recently spent two months in China and had interactions with at least eleven choruses, in four different cities, ranging from elementary school students to conservatory students, as well as community choruses and church choirs. Only two choruses out of the eleven could read relatively well from staff notation. One choir consisted of members who used both staff notation and Chevé notation, which made the conductor’s job quite difficult in rehearsal. The rest of the choruses used only Chevé notation. Seven conductors were fluent in both staff and Chevé notation, and the rest could only read Chevé notation. I, myself, ever since elementary school, used to transcribe choral music from staff notation into Chevé notation, which laid a firm foundation for my harmonic analysis skills. Yet, after being away from the Chevé for over twenty years, I found rehearsing choruses from Messiah in Chevé notation an extremely difficult task.

Several inconveniences come to mind when contemplating the use of Chevé instead of staff notation for general use: publishing standard repertoire in Chevé would mean much time spent in “translation”; secondly, repertoire would be limited to only tonal music; and thirdly, with both systems existing side by side, confusion would result especially when one has long been universally accepted. In 1931, the Montreal education authorities, citing three similar reasons, “banished the Tonic Sol-fa notation[4] from their schools” (Coward and Whittaker 1931). Sir Henry Coward pleaded the Case for Tonic Sol-fa notation on behalf of the people who do not learn instruments at home.

“The chief thing in teaching sight-singing is to give the pupil a grasp of the mental effect of each note of the scale, without confusing the mind with the many intricacies of the Staff notation. These complexities are bewildering enough to those who master them while slowly acquiring the technique of, say, the pianoforte or violin, &c.; but to the young they are most perplexing, and divert the mind from acquiring the mental grasp of the sounds. This generally ends in the pupil assuming that learning the notation is learning music. Thus we get a race of alleged musicians who cannot even attempt to read at sight… the best readers of the Staff notation are almost invariably good Sol-faists.” (Coward and Whittaker 1931)

I believe that transcribing or translating choral music from staff notation to the Chevé is, actually, a good theoretical exercise for any musician, since it requires the musician to know the exact chord upon which the tonal centre shifted so that he or she can indicate the new “1 = ____”. I used to use this opportunity to analyse and memorise the composition that I was about to conduct. Personally, I no longer have the time to sit and translate For Unto Us A Child is Born from the Messiah any more (I did when I was in high school), but I am sure some dedicated musician is devoting a lot of time doing this since I have seen the entire Messiah published in Chevé during my most recent visit in China. Another limitation is that since the Chevé is a “movable do” system, it requires that a tonal centre is always present; therefore singing compositions such as Stravinsky’s Dove Descending would be out of the question. But, as one of my colleagues pointed out, if a choir has acquired the technique to sing atonal compositions, then they can simply change the notation to the “fixed do” system and all is well again. One can see, from example 2, that the Chevé uses accidentals just as in the staff notation, so it would be quite easy to simply make 1 = C permanently and transcribe all the notes as their sounding pitch. And most likely an amateur choir would not sing atonal music; and a well-trained choir that can sing atonal music probably would be reading the staff notation anyway. However, I did find rehearsing large works such as The Yellow River Cantata or Messiah, with the choir using Chevé and the pianist using staff notation, quite confusing. Any kind of notation could be compared to a language – it is a graphic code translated into sounds. Reading the Chevé and the staff notation side by side is like reading Chinese and English side by side. Chevé indicates the scale degrees of the diatonic scale just like the Chinese characters often convey the meaning of the word but not how it is pronounced; while the staff notation indicates precisely the pitch, like English letters reveal the sound of the word. I found this gymnastic exercise for my brain interesting but not necessary, especially the time wasted in trying to find the corresponding measure in both scores just so that the pianist and the choir would be on the same page, literally.

I taught aural skills for several years to music school students and have found the same issues that both Coward and Bullen mentioned, which was many pianists who could play complex music but could not vocalize a simple melody. I attribute this symptom to the fact that keyboardists have no control over the intonation of their instruments; therefore they are not engaged as an active listener. Christina Ward said in her book that one could not sing in tune if one did not know how to listen. I also have found vocalists who can sing very well by ear, who can pluck notes out on the piano, but could not sight-sing. I found it much easier just to tell these young adults, the pianists and the vocalists, to sing everything they play and play everything they sing. I did, however, find the Chevé useful for teaching young children who had not begun instrumental studies. I have used the Chevé notation, combined with Curwen’s hand signs, and the Kodaly method to teach children ages 5 through 8. The students made the transition into staff notation quite easily after two years of instruction, and they have a firm grasp on intervallic relationships as well as basic knowledge on tonal functions of each scale degree.

The truth is a master educator can use many methods and make improvements or improvisations to fit his or her needs. The difficulties for staff notation to become common practice for choral musicians in China is at least two fold. The education authorities change their tune quite often: the policy for the last ten years has been that schools must use the Chevé notation for all musical learning, despite the fact that ten years ago it was all staff notation. And the wind might change again, so the verdict is still out as to what the children will be learning. Secondly, the percentage of music teachers who are capable of transitioning their students from the Chevé into staff notation are quite small. Actually, music teachers who know how to teach pupils to sight sing without the aid of an instrument are not easily found; luckily, more and more children are learning to play instruments. Maybe in another half a century, with new policies regarding the arts, China will finally be rid of the Chevé.

Bibliography

- Bullen, George W. “The Galin-Paris-Cheve Method of Teaching Considered as a Basis of Musical Education.” Proceedings of the Musical Association (Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of the Royal Musical Association), April 1878: 68-93.

- Coward, Henry, and W. G. Whittaker. “The Case for Tonic Sol-fa Notation in the Schools.” The Musical Times (Musical Times Publications Ltd.) 72, no. 1058 (April 1931): 334-335.

- Ellerton, G. M. K. “Chevé Notation.” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular (Musical Times Publications Ltd.) 23, no. 474 (August 1882): 454-455.

- Stevens, Robin S. “Samuel McBurney: Australian Advocate of Tonic Sol-fa.” Journal of Research in Music Education (Sage Publications Inc. ) 34, no. 2 (1986): 77-87.

- Wareham, Fred. W. “Tonic Sol-fa and Staff Notation Systems.” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular (Musical Times Publications Ltd.) 23, no. 473 (July 1882): 400-401.

- Weidenaar, Gary. “Solmization and the Norwich and Tonic Sol-Fa Systems.” The Choral Journal (American Choral Directors Association) 46, no. 9 (March 2006): 24-33.

Edited by Mirella Biagi, UK/Italy

[1] Bullen, George W. “The Galin-Paris-Cheve Method of Teaching Considered as a Basis of Musical Education.” Proceedings of Royal Musical Association, 4th Sess. (1877-1878): 68-93

[2] Ellerton, G. M. K. “Chevé Notation.” The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol.23, No. 474 (Aug. 1, 1882): 454-455

[3] The “do” is determined only by key signature. If the music is in E Minor, then the tonal center is no longer “do”, but “la”, which is the 6th degree of the diatonic scale.

[4] The Tonic Sol-fa notation used in Great Brittan is similar in principle with the Chevé, but differs in notation. I use these arguments because all of these concerns apply to the Chevé notation.