Choral Music in Slovenia

By Tomaž Faganel conductor & musicologist, lecturer, juror, singer

Since the Middle Ages, singing has been the central identifying cultural and musical conception for Slovenes in the land between the Alps and the Adriatic, closely connected with the nation’s historical and cultural tradition. The remains of medieval culture, historic sources, codices, and art placed choral music composition a full millennium back into the past. The rare remaining documents and the oldest written sources of the broader area confirm the presence of Latin chant, and of a wide range of secular song in the vernacular of the time (e.g. Oswald Wolkenstein 14th century), while some surviving codices (Stična MS, first half of the 15th century), later musical sources (Kranj Antiphonal, late 15th century), and many multi-genera musical arrangements mention singing in Latin in monasteries and city churches. The chronicler of the Episcopal visitation to the church in Aquileia mentions singing being performed ‘under the rules for composition’ current at the time – 1486 – and cites sister Aurora, sopranist and organist from Velesovo monastery.

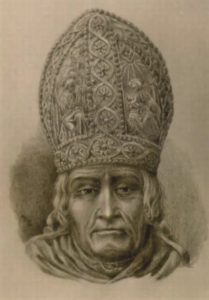

Balthasar Praspegius, a scholar from Mozirje, published a Latin dissertation on singing, in Basel in 1501. An earlier scholar was Jurij Slatkonja (Georg Chryssipus, 1456–1522), founder of the court chapel in Vienna (today’s Wiener Sängerknaben), Bishop of Vienna and leader of the emperor’s musicians. Some of the music attributed to him was harmonized by Heinrich Isaac. The Ljubljana priest Georgius Prenner, the author of over 39 motets, was also a Viennese court musician.

In the mid-16th century, Protestantism also influenced church music through texts in Slovenian. Primož Trubar (1508–1586) supported singing in the vernacular during a religious renewal which brought about the first Slovenian books and songbooks. Numerous songbooks, church literature, and a translation of the Bible by Jurij Dalmatin confirm the rise of a sense of nationality, evident in music, language, and general culture.

In a conflict of religious renewal and subsequent counter-reformation, Jacobus Handl-Gallus (1550–1591), the undisputed giant of 16th century European music, choir master, humanist and prolific composer who considered himself Carniolus (from Carniola, the ancient name for Slovenia), ventured forth from present-day central Slovenia into the world, finally reaching Prague. His enormous printed opus of motets (374), masses (16) and Latin secular songs (100) is one of the most vital and evolutionally important pillars of Renaissance music. After him another ‘Carniolus’, Gabriel Plautzius, entered the world of German-type early Baroque with a collection of motets and church concerts with continuo (1621).

Monasteries and cities and their schools, emphasizing music and singing, remained the centers of musical power in Slovenia throughout the 17th century. From 1597, a central role was played by the Jesuit college, where all the important intellectuals and musicians had studied. The influence of Jesuit tradition in Slovenian music was felt at least until the end of the18th century. The composer Janez Krstnik Dolar (1621–1673) from Kamnik, later principal of the Austrian Jesuits and a musical leader in Vienna, also originated from this institution. Time has preserved 14 of his compositions: masses, psalms, sonatas and ballets, in Italian-type Baroque concerto style.

The choral music of the late 17th and entire 18th centuries remains mainly linked to monasteries, city churches, chapels and schools. Exclusively vocal-instrumental music arrived in Slovenia through migrations of musicians, priests and friars from the south German, Czech and Italian areas, and reflects the classicism of many forms only in basic outlines. Musical and historic sources testify to widespread singing activity in Novo Mesto, Kamnik, Ljubljana, and some seaside cities and other towns. After Trubar, choral or sung church music was no longer Slovenian; the majority of our known musicians of the time were not of Slovene origin, much less was their repertoire Slovenian.

We can only talk of truly ‘Slovenian’ choral music, and indirectly church choral music, being created and performed after the mid-19th century, when Gregor Rihar (1796-1863) – the first to compose in Slovenian – strengthened the vitality of Slovenian choral music mostly through his own compositions. In the middle of the 19th century, middle-class musicianship was revived through singing, which also influenced the development of choral singing and composing in the public music schools which were beginning to appear. National self-awareness and the cultural awakening of nations after 1848 provided additional encouragement for the development of choral music, especially in the Austro-Hungarian empire, of which Slovenia was then part. Since then, choral music in Slovenia has had Slovenian texts, an awareness of Slovenian nationality, and close links with Slovenian poetry. It found its earliest momentum among Slovenes in Vienna, and spread in Slovenia through reading societies, new choirs and associations. Its musical and stylistic roots, however, lie in middle-class music of the German cultural world and in Romanticism which was felt in Slovenian music only after a perceivable delay owing to several cultural-sociological reasons.

Many composers wrote for choirs: Davorin Jenko, Jurij Fleišman, Miroslav Vilhar, a number of members of the Ipavec musical family, Anton Hajdrih, and two very important naturalized Czech musicians in Slovenia, Anton Nedvěd and Anton Foerster, among others. The evolution of choral music was also encouraged by music societies, the foremost being – after 1872 – Glasbena Matica, and by Matej Hubad and Fran Gerbič, important musicians. Publishers and music schools also helped; the Slovenian Caecilian Society’s church music school and Cerkveni glasbenik (Church Musician) journal were dedicated to the development of church music. Its natural progress in style was partly diverted by the Caecilian reform of church music, and was temporarily directed toward evolutionary neutral polyphony and Latin, but the Slovenian tendency persevered. At the turn of the century, the circle of composers around Anton Foerster and Hugolin Sattner was most important. The publication of Novi akordi (New Chords) journal (1901-1914), edited by Gojmir Krek, was important in giving a contemporary view of music, also publishing most of the choral works of some of the aforementioned musicians but publishing mainly the works of Emil Adamič, Anton Lajovic, Risto Savin, Josip Pavčič, Stanko Premrl, Janko Ravnik and Marij Kogoj.

After World War I, Slovenian choral music develops in directions set by Novi akordi and an extended circle of composers, following several different lines and disunited in style. While mostly impervious to the newest European musical trends, Slovenian music showed tiny flashes of impressionism, and later, neoclassicism as an exception to the rule. It was to be found mostly in a post-romantic frame with recognizable nationalist features, and it co-depended on the level of the choirs performing it. The parallel life of church choral music is not very different, but reflects specifics of its type. Its central creators after partial deviation from the Caecilian movement were Stanko Premrl, Franc Kimovec, and especially Vinko Vodopivec, Matija Tomc and Alojzij Mav before and after WWII.

World War II interrupted the evolutionary flow of choral music and a new form of choral music arose: strongly motivated choral songs of resistance with recognizably revolutionary elements, which then evolved through the addition of mainly cultural-political emphasis after 1945, owing also to planned and directed cultural policy. Many composers also active in other creative fields devoted themselves to this choral type: Karol Pahor, Pavel Šivic, Marjan Kozina, Radovan Gobec, and others.

A colourful variety of styles remained a characteristic of Slovenian choral music throughout the following decades, although remains of Romanticism and its derivatives could still be perceived. A deviation from state-directed culture is represented by composers who found an opportunity to make a partly independent musical declaration by means of frequent expressionist notes in socially-themed poetry. Vinko Ukmar and Marijan Lipovšek reached for such contents in their choral compositions and indicated a possible direction of contextual-artistic relaxation and a meeting with contemporary features of the European choral music of the time.

A gradual contact of Slovene composers with developments in contemporary music in Western Europe in the late 1950s and early 1960s can be perceived in their choral music. Some anthological works, mainly by Lojze Lebič, and later by Jakob Jež, move away from the usage of the time and continue (followed by the compositions of Uroš Krek and others), to make available a wide variety of styles and possibilities for the human voice and for choirs during the mid-1970s.

Over the decades, performers consistently improved in quality, ranging from the best amateur formations, to the Slovenian Radio semi-professional choir (which had been moving towards modern performing standards since the late 1960s), to the professional Slovenian Chamber Choir (since 1991). All these formations represent important encouragement for composers. The choral department of the Public Fund for Cultural Activities has had significant influence on the evolution of choral music and performance norms through its organizational-musical support, usefully complementing institutional and private forms of conductor- and singer-education.

Church choral music is more cautious in searching for the new, and the influence of Caecilian aesthetic norms and of several decades of circumscribed activity is still being felt. The first steps toward the contemporary in church choral music were made by Jože Trošt, followed by Maks Strmičnik, Andrej Misson and Ivan Florjanc, also renowned outside the field of choral music. The current cultural-aesthetic climate has blurred the line between sacred and profane through differing aesthetic views, composers’ solutions and techniques, and the quality of performance. Ambrož Čopi, Damijan Močnik and some representatives of the upcoming generation of composers follow the tendencies of the time and the ability of performers.

When speaking of Slovenian choral music, we should not overlook folk music. From the mid-19th century, popular influences have been present. Various types of traditional songs for several voices remain an important and enduring phenomenon for national identification, although these original forms are gradually dying out. However, folk melodies can be recognized in current musical compositions, traditional harmonization, skillful disguises and concert adaptations of folk music.

The events of recent decades and the current climate in the Slovenian choral world encourage composers (some of whom are themselves active conductors) and the colorful pyramid of various choirs of all types offers plenty of space for them to develop their inspiration and to find compromises between ideas, options, and reality, developing a tuneful relationship between pleasure and serious study. They may use basic traditional themes in their compositions, or give free rein to their curiosity in searching for new solutions. Performing choirs and their conductors all face similar questions on aesthetics, professionalism and artistic responsibility.

Edited by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy