Claudio Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers 1610) – SV 206

By Uwe Wolf, musicologist

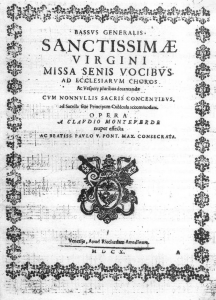

The Vespro della Beata Vergine is part of a collection which appeared in 1610 bearing the title “Sanctissimae Virgini Missa senis vocibus, Ac Vespere pluribus decantandae.”[1] It begins with the Missa In illo tempore, a mass which parodies Nicolas Gombert’s motet of the same name, and is followed by the sequence of pieces known as the Vespers of the Blessed Virgin, which we present in our score: responsory, five vesper psalms for Marian festivals, hymn and magnificat (in two versions), as well as the concerti Nigra sum, Pulchra es, Duo Seraphim, Audi coelum (interpolated between the psalms), and the Sonata sopra Santa Maria.

Very little is known about the genesis of the Vespers of the Blessed Virgin, or more specifically, about the collection containing it. The collection was first described in July of 1610 by Monteverdi’s assistant Don Bassano Casola (the dates of his lifetime are unknown). In a letter to Cardinal Ferdinando Gonzaga, the younger son of Monteverdi’s noble employer Vincenzo Gonzaga, Casola wrote that Monteverdi’s six-voice “Messa da Cappella” on themes from Gombert’s motet “In illo tempore” was currently being published. Along with the mass, psalms for a Vespers of the Blessed Virgin (“Salmi del Vespro della Madonna”) were being printed. These were to consist of varying and diverse inventions and harmonies over a canto fermo (cantus firmus). Casola further reported that Monteverdi intended to travel to Rome in autumn, in order to personally dedicate the collection to his Holiness the Pope.[2]

The print does indeed bear a dedication to Pope Paul V which is dated 1 September 1610. Researchers unanimously assume that Monteverdi wished to recommend himself as a composer to the Pope – and most likely to other potential church employers – with this collection. The characteristic of a “portfolio” has left an essential impression on the 1610 print in many respects, and it is certainly an important key to understanding the collection. Certainly, this was the reason for combining a mass and vespers music in one volume. The mass was traditionally conservative, while more modern trends[3] were pursued in the vespers; Monteverdi utilized the tension between these contrasting idioms more than any other composer of his time.

On 1 September, the date of dedication, the print may well have been nearly complete, since Monteverdi set out for Rome shortly after this date, already arriving at the beginning of October.[4] Monteverdi’s attempts to attain entrance into the Seminario Romano for his son Francesco were the main purpose of his trip to Rome. However, the trip was hardly successful: Monteverdi neither succeeded in securing a place for his son at the Seminario nor did he obtain an audience with the Pope to present his print in person.

Monteverdi may possibly have met the Pope already in 1607 in Mantua. This could explain why Monteverdi quoted his opera L’Orfeo,[5] which had been performed for the first time that year in Mantua, in the vespers’ responsory and magnificat.

Monteverdi’s intention of travelling to Rome was probably also the motive for the publication of the mass and vespers, which might have been planned for a longer period of time, but had not yet been carried out. Casola’s first reference to the collection already associates it with the trip to Rome (cf. above). Publication most likely took place under considerable time pressure, since Casola mentions the work on the print in July as a novelty, the dedication is dated 1 September, and Monteverdi already had to leave for Rome shortly after this date. At any rate, such time pressure could explain certain discrepancies in the print of 1610, especially the existence of deviant versions of various pieces in the basso continuo score (see below) – which are presumably earlier – as well as a larger number of printing errors.

Whether a “premiere performance” of all or some of the pieces took place before the collection went to press is unknown. While it seems more plausible in the case of the mass that it was created especially for this publication, the instruments employed in the three movements with obbligato instruments (Nos. 1, 11 and 13) vary considerably, which allows for the assumption that at least some of these pieces were composed for different occasions,[6] with instrumentation specifically tailored to the particular performance situations. Differing versions of the basso continuo and the vocal parts in no less than five pieces allow the assumption that existing pieces were revised.

However, church music was not actually part of Monteverdi’s vocational obligations in Mantua, though this does not rule out that he also took part in church music performances at important festivities.[7] Various hypotheses on the occasion and purpose of the compositions have been brought forward in the last fifty years, none of which could be supported by any documentary evidence at all up until now .[8] No performances can be verified for Monteverdi’s Venetian period either (although we can safely assume that at least individual sections were performed). By contrast, when Monteverdi applied for the position of maestro di cappella at San Marco in Venice, the 1610 print was surely an essential argument for actually entrusting him with the position.[9]

The 1610 Print

Along with Monteverdi’s later collection Selva morale e spiriuale (1641), the print of 1610 belongs to a category referred to as repertoire prints, which unite in one volume music for the two most important worship services of the universal church, the Mass and Vespers. The description of the collection in the signature marks on the vocal parts is in keeping with the tradition of such repertoire prints: “Messa & Salmi di Claudio Monte Verde .”[10] Although the collection’s contents possess parallelisms in genre with a number of other repertoire prints (mass, psalms, magnificat and motets),[11] there are major differences between Monteverdi’s collection of 1610 and other contemporary prints of this kind:

- Psalms and concerti are not in separate categories, they alternate.

- The magnificat settings are two versions of the same composition.

- The mass setting adopts a very archaic form of parody mass.

- Psalms and magnificat follow a clearly-defined and even named common principle.

Especially the first point has been the topic of much discussion. The hypothesis that we have a complete vespers setting at hand – and not merely a series of vesper compositions – is primarily and definitively based on this fact. We know of only one other collection with this type of combination,[12] and it is not truly comparable.[13] The presence of the two magnificats is just as puzzling, and may support the hypothesis of a coherent vespers setting. Many collections contain numerous magnificats, but these usually differ in type and psalm tone, in order to recommend a given collection for as many vespers and occasions as possible.[14] Together with the ritornelli ad libitum (in No. 2) and the falsobordone notation in the vocal parts of the responsory, the unusual presence of two versions of the same magnificat (with and without obbligato instruments) has awakened the impression that we are dealing with one and the same coherent vespers setting in two versions (with and without obbligato instruments) – and not with a collection kept as general as possible.[15]

By contrast, points three and four underline the very unusual programmatic demands of the collection, in which Monteverdi wishes to display a stylistic variety with high impact. Stylistic extremes are evident in the consciously conservative mass and the innovative concerti: both are extreme in the forms found here, but neither is unusual when taken for itself. However, the psalms and the magnificat are the most breathtaking. “Vespro della B. Vergine da concerto, composto sopra canti fermi” is the programmatic subtitle found in the basso continuo score,[16] which describes the daring combination of the retrospective cantus firmus technique with the highly-modern concerto style in one composition. As was the custom, Monteverdi varied the style from psalm to psalm, but still remained true to his chosen fundamental principle. As with the parody form of the mass, Casola had also described this fact in his letter to Ferdinando Gonzaga as a prominent characteristic: “Salmi del Vespero della Madonna, con varie et diverse maniere d’inventione et armonia, et tutte sopra il canto fermo.”[17] Even if one can dispute about liturgical unity (see below), compositional and artistic unity are in themselves already attested to by this unusual subtitle.

This programmatic concept of the 1610 collection may also be responsible for points one and two as mentioned above. Taken for themselves, the inserted concerti and the sonata follow a logical order of increasing the number of participants, a standard feature of many collections of the time. The positioning between the psalms sharpens the contrast and increases the collection’s coloration. There is also evidence for the fact that motets (to which the concerti belong) were performed between the vesper psalms. This type of order would therefore have been expedient, exemplary, and programmatic – independent of any general liturgical context. The two versions of the magnificat[18] could also be indebted to Monteverdi’s incentive to prove his capability to create equivalent compositions: one for a large instrumental apparatus, and an a cappella version.

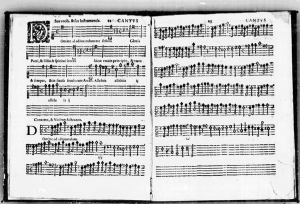

In all of the movements scored for instruments where the actual number of participants exceeds the number of available part-books (i .e ., seven), vocal and instrumental parts are printed together on each left and right hand facing page of a part-book, respectively. The page turns for these shared parts concur . The distribution of the additional voices was carried out differently in the part-books for each composition. In the three works with obbligato instrumentation (Nos. 1, 11 and 13), the same instrument is hardly ever assigned to the same vocal part twice. The Missa and Magnificat are treated as works with more than one movement. When voices pause during a certain piece, the marking “tacet” is used. Other compositions are treated as individual works of their own, since these are not mentioned in the part-books which are not involved.

The oversized “Bassus generalis” part-book contains, for the most part, a basso continuo part largely without figuration, which still frequently takes on the form of a basso seguente in longer passages. On the other hand, the four concerti are printed in full score in the “Bassus generalis,” as was the general custom with this type of music.[19] Full scores are also extant for the Crucifixus of the mass, for Nos. 13g, and 13l. This part-book also contains short scores for Nos. 1 (two voices), 4 and 6 (three voices). In our edition, we therefore generally refer to a “basso continuo score.” Incidentally, the “Bassus Generalis” is already labeled as the “Partitura del Monteverde” in its signature marks. In the organ part published within the performance material of this edition, we have followed the notation of the short score and print the staves of orientation as given in the original “basso continuo score”; in addition, we have supplemented the vocal texts which were not rendered in the original basso continuo score.

Liturgical Problems

In the monastic hours of prayer, vespers consists, in essence, of the responsory, five psalms, which vary according to the church festivals, and the Magnificat. Other spoken texts may be added. Psalm and Magnificat are framed by antiphons (sung before and repeated after the psalm), which establishes a reference to the respective festivals.[20] The psalm tone conforms to the tone of the antiphon; various cadential phrases (differentiae) of the psalm tones facilitate reconnecting with the antiphon. For a long time, literature on Monteverdi’s Vespers has described the fact that no Marian festival exists with the psalm tone order which occurs in the print of 1610. Numerous hypotheses fall into line with these findings, ranging from the assumption of special liturgies,[21] via the assertion that tonal reference was no longer taken seriously in Monteverdi’s age, to the denial of liturgical unity, which prevails today.

Many indications, however, point to a liberal treatment of the psalm tones at least, although it is not entirely clear what this means in detail. Apparently, the differentiae[22] were no longer in use. Collections exist which allegedly offer material for all of the high festivals of the church year, containing all the psalms implemented in the vespers, but all using just one psalm tone[23] apiece. Monteverdi also uses final cadences for the psalm tones which were apparently the only ones remaining. He sometimes employs the liturgical tones at different levels – at the beginning and end of the psalm as well – making a coherent return to the antiphon impossible.[24] In his overview of vespers for the church year, Adriano Banchieri lists only psalm tones[25] which vary from festival to festival for the magnificat, additionally underscoring the apparently slight significance of the psalm tones (and hence for the antiphons as well?).

The position of the concerti between the psalms is most often explained with the reasoning that instead of a repetition of the antiphon these concerti were performed as substitutions. This theory has been reinforced by accounts of Vespers in which motets were performed between the psalms. However, accounts of vesper services in which motets were performed between the psalms[26] must not inevitably be interpreted as documentary evidence that they were substituted for the antiphons. This could have been a practice which was not “liturgical” in a narrower sense of the word, since vespers of the early seventeenth century were nearly concert-like in character. This might possibly explain more conclusively why Monteverdi exemplarily placed concerti between the psalms than the idea of antiphon substitution.[27] In principle, one can only regret the lack of research on liturgical practices at this point, without which a solution ultimately cannot be given.

By now, the majority of researchers assume that the vespers part of the 1610 print cannot be viewed as a liturgical entity for which a contemporary performance can be postulated.[28] But rather, Monteverdi would have expected individual sections to be performed in different contexts. The fact that Monteverdi broke with the custom of placing the concerti in a separate section of the print – in addition to the order of psalms and the magnificat in their liturgical succession customary in prints of the vespers – and set them between the psalms instead, could indicate an intended order of performance. This, in turn, should be understood as “exemplary” and not as an actual “performance unit.”

Editions of the Vespers – A Historical Overview

Over the course of the years, the Vespers of the Blessed Virgin have been the subject of more editions than any other seventeenth-century composition. Carl von Winterfeld[29] was the first researcher to publish isolated examples. Gian Francesco Malipiero brought out the first edition of the complete collection in 1932[30]; it appeared within the complete edition of Monteverdi’s works, of which he was the general editor. It was not an academic edition by today’s standards. No critical remarks were given, and only a few footnotes make reference to grave deviations from the source. The numerous mistakes in the musical text are partially a result of the editor’s alterations, and even more so of misinterpretations of the historical evidence handed down to us. Nevertheless, his edition was the starting point for a series of editions (which frequently adopted Malipiero’s mistakes, as must be admitted). Practical editions followed, which were often marked by encroachments of various kinds: re-instrumentation, abridgements, rearrangements, and transcriptions of the late mensural notation, which seems absurd to us today. Simultaneously, editors begin to omit parts of the print of 1610 (concerti) or amend it (antiphons); in both cases, the goal is the construction of a liturgical vespers.[31]

For a long period of time, Gottfried Wolters’ edition (1966) of the complete vesper section of the print (with only the Magnificat à 7) was authoritative for musical practice.[32] Wolters’ edition is the first which contains critical remarks, albeit incomplete. The note values and the meters are still subject to drastic changes. Although the score only contains the original instrumental voices, Wolters supplied a full orchestration of the entire Vesper within the part material, as was the case in many editions. Fortunately, he retained the historical instrumentation to a large extent. Liturgical supplements (antiphons) are mentioned in an appendix. Wolters’ edition has influenced the transmission of the Vespers as no other. With Clifford Bartlett’s edition of 1986 (rev. 1990/2010[33]), a new series of critical editions based on the source was initiated. However, the musical substance was alienated anew, due to problematical hypotheses (cf. transpositions and triplet transcription in the sonata, as mentioned below[in the original foreword; this is not part of this abridge edition]). On the other hand, problems of the 1610 print are left unsolved, and are passed on to performers due to exaggerated adherence to the source.[34] Three new editions have also appeared in the 21st century (the present one is the fourth). Among these, Antonio Delfino’s[35] new edition, which has been published within the framework of the new complete edition of Monteverdi’s works (2005), deserves mention. It is the first (and only) edition up until now which meets modern expectations of a critical edition, especially in its treatment of the historical material handed down to us and in its objective rendition of the musical text. On the other hand, the shortened forms of triple meter (transformed into sextuplets) in Delfino’s edition are disturbing and no longer up-to-date; these result from the obsolete guidelines of the Monteverdi edition.

Claudio Monteverdi: Vespro della Beata Vergine, edited by Uwe Wolf, Stuttgart (Carus) 2013. Translation: Greta Konradt. Used with permission”. (Abridged. This is followed by chapters on notation publication and performing practise in the original edition)

Uwe Wolf studied musicology, history, and historical ancillary science at Tübingen and Göttingen. After receiving his doctorate in 1991 he was a research fellow at the Johann-Sebastian-Bach-Institut in Göttingen. From 2004 he worked at the Bach-Archiv Leipzig. There he directed one of the two research departments, was substantially responsible for the redesigning of the Bach Museum, and he developed the digital Online-Projekt Bach. Since October 2011 he has been the Chief Editor at Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart. He has taught at various universities and also belongs to the editorial boards of several complete editions. Email: uwolf@carus-verlag.com

Edited by Taylor Ffitch, USA

[1] For the complete title cf . Critical Report.

[2] In the original: “Il Monteverdi fa stampare una Messa da Cappella a sei voci di studio et fatica grande, essendosi obligato maneggiar sempre in ogni nota per tutte le vie, sempre più rinforzando le otto fughe che sono nel motetto, in illo tempore del Gomberti e fà stampare unitamente ancora di Salmi del Vespro della Madonna, con varie et diverse maniere d’inventioni et armonia, et tutte sopra il canto fermo, con pensiero di venirsene a Roma questo Autumno, per dedicarli a Sua Santità .” This letter was first published by Emil Vogel, “Claudio Monteverdi . Leben und Wirken im Lichte der zeitgenössischen Kritik und Verzeichnis seiner Werke,” in: Vierteljahrsschrift für Musikwissenschaft 3 (1887), p . 430 . The letter has been cited often in literature on the Vespers.

[3] Cf . Uwe Wolf, Notation und Aufführungspraxis. Studien zum Wandel von Notenschrift und Notenbild in italienischen Musikdrucken der Jahre 1571−1630, Kassel, 1992, vol . I, p . 44ff .

[4] One must consider that at the time, music prints could only be produced in a few locations. Monteverdi’s collection appeared in the very center of music publication, in one of the large printing offices of Venice (Riccardo Amandino). From there, the copies first had to reach Monteverdi.

[5] Jeffrey Kurtzman, The Monteverdi Vespers of 1610. Music, Context, Performance, Oxford, 1999, p. 14. The Pope was staying in Mantua in May 1607. The performance of L’Orfeo had already occurred in February of 1607, but it still could have been a topic at the court.

[6] For example, the absence of a third cornetto part in the responsory (the part of the first viola would match perfectly) is just as difficult to explain as the absence of violas in the Sonata and the Magnificat .

[7] Cf . among others John Whenham, Monteverdi: Vespers 1610, Cambridge, 1997, p . 29ff .

[8] Various theses are summarized by Kurtzman 1999, p. 11ff.

[9] A Venetian document mentions that not only the test pieces Monteverdi performed, but also his printed works spoke for his election (cf . Whenham, 1997, p . 40 and Kurtzman, 1999, p . 52f). We can presume with certainty that only church works were consulted. Aside from the early three-voice pieces Sacrae cantiunculae (1582) und the print of 1610, Monteverdi had not published any sacred works.

[10] Michael Praetorius abbreviates the title even further and speaks of Monteverdi’s (“Claudii de Monteverde”) “Psalmi vespertini,” a common title-page formulation of the time (Syntagmatis Musici … Tomus Tertius, Wolfenbüttel, 1619, reprint, Kassel, 1954 (Dokumenta musicologia, I:XV), p. 128; Praetorius describes the verse sequence of the hymn “Ave maris stella” here) .

[11] Some examples: Giovanni Paolo Cima, Concerti ecclesiastici, Milan, 1610; Francesco Rognoni Taegio, Messa, salmi intieri et spezzati, Magnificat, falsi bordone & motetti, Milan, 1610; Valerio Bona, Messa e vespro a quattro chori, Venice, 1611; Tomaso Cecchino, Psalmi, missa, et alia cantica, Venice, 1619; Sigismondo Arsilli, Messa, e vespri della Madonna, Rome, 1621.

[12] Paolo Agostini, Salmi della Madonna, Magnificat A 3. Voci. Hinno Ave Maris Stella, Antiphone A una 2. & 3. Voci. Et Motetti. Tutti Concertati, Rome, 1619.

[13] On the one hand, the antiphons do indeed have antiphonal texts, and on the other, they are – exemplarily? – noted between the psalms . However, in the table of contents (tavola), both are listed in separate groups.

[14] Uwe Wolf, “Et nel fine tre variate armonie sopra il Magnificat . Bemerkungen zur Vertonung des Magnificats in Italien im frühen 16 . Jahrhundert,” in: Neues Musikwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch 2 (1993), pp . 39−54.

[15] Manfred H . Stattkus also sees two versions of the same work (SV 206, 206a); cf. Claudio Monteverdi. Verzeichnis der erhaltenen Werke. Kleine Ausgabe, Bergkamen, 1985, p . 50ff .

[16] Heading of the responsory in the basso continuo score.

[17] Cf. footnote 2.

[18] Scholars have discussed several questions, such as: which of the versions is the earlier one, are they two versions of the same composition at all, or are they merely similar compositions? (see Whenham, 1997, p. 78f. and Kurtzman, 1999, p. 264ff., with a summary of the discussion to date). Meanwhile, some indications speak in favor of the idea that the interrelationship of the two Magnificats is more complicated, and cannot simply be described with the one-dimensional terms “first version” and “second version”: Both compositions contain passages for which one could well argue that they should be considered to be earlier material. Most likely, precursors existed which influenced one another reciprocally.

[19] The score has no text, since a separate vocal part exists; by contrast, secular monodic music was only published in score form.

[20] Cf. Whenham, 1997, p. 8ff. on the structure of the vesper service after the reforms of the Council of Trent.

[21] The most prominent example is Graham Dixon’s hypothesis that the vesper is actually not in honor of the Virgin Mary, but was composed for St. Barbara of Mantua, following a special liturgical form for Mantua (“Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610: „della Beata Vergine“?,” in Early Music 15 [1987], pp . 386−89) . This view must primarily be countered with the argument that a vesper according to Mantuan liturgy would hardly have been fitting for a dedication to the Pope, and probably not even for publication.

[22] Whenham 1997, p . 22; Pietro Pontio, Ragionamento di musica, Parma, 1588, reprint, Suzanne Clercx (ed .), Kassel et al ., 1959 (Documenta Musicologica, I:XVI), p . 97f .

[23] For example, Giovanni Giacomo Gastoldi, Psalmi ad vesperas in totius anni solemnitatibus, Venice, 1588, 21592; Adriano Banchieri, Salmi festivi intieri, coristi, allegri, et moderni, Venice, 1613 . Cf . also Whenham, 1997, p. 15.

[24] For details, cf . Whenham, 1997, p. 60ff.

[25] Adriano Banchieri, L’Organo Suonarino, Venice, 11605, reprint, Amsterdam (together with the editions of 1611 and 1638), n.d. (Bibliotheca Organologica, XXVII). In the “Norma a gli organisti” (p . 118ff.), only the hymn and the magnificat tones in both vespers are named for the various feasts.

[26] Whenham, 1997, p. 20. Banchieri refers to organ playing between the psalms (L’Organo Suonarino, Venice, 21611, p. 45 of the facsimile edition, see footnote 25).

[27] Cf . also Whenham, 1997, p . 19.

[28] Ibid ., p . 2, and Kurtzman, 1999, p . 39 .

[29] Carl von Winterfeld, Johannes Gabrieli und sein Zeitalter, Berlin, 1834, reprint, Hildesheim 1965, vol. III, p . 112f. (Dixit Dominus) and p. 114f. (Deposuit of Magnificat a 7) .

[30] Monteverdi Opere, vol. XIV, parts 1 and 2.

[31] For information on editions up to 1999, cf. Kurtzman, 1999, p. 15ff.

[32] Claudio Monteverdi, Vesperae beatae Mariae virgini. MarienVesper 1610, ed. by Gottfried Wolters, Wolfenbüttel and Zürich, 1966.

[33] Monteverdi, Vespers (1610), revised editions 1990 and 2010, respectively, ed. by Clifford Bartlett, Huntingdon, 1990 and 2010.

[34] For example, many incongruities still remainin the edition: Claudio Monteverdi, Vespro della beata Vergini da concerto, composto sopra canti fermi SV 206, ed. by Jerome Roche, London et al., 1994, such as rhythmic deviations between the bass and the basso continuo, or divergent mensural notational signs and time sifnatures

[35] Claudio Monteverdi, Missa da capella a sei. Vespro della Beata Vergine, editione critica di Antonio Delfino, Cremona 2005 (Claudio Monteverdi: Opera Omnia. Edizione nazionale a cura della Fondazione Claudio Monteverdi, Volume nono)..