The Colombian Cánticas of Luis Antonio Escobar

Joaquin Zapata, Master’s Degree in Choral Conducting, Eafit University, Medellin, Colombia

This article recognizes the prolific composer Luis Antonio Escobar and focuses on the analysis of one of his Colombian Cánticas, and on the correlation that exists between the composer and the work. It also discusses in concrete terms the ways in which, in the contemporary world, local cultural traditions seep into the creation of universal music and specifically, of Colombian music.

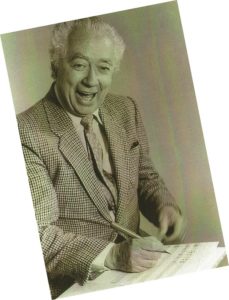

When Luís Antonio Escobar died in 1993 in Miami, where he held the position of cultural attaché, he was already clearly recognized as the composer of a significant number of works, especially in the relationship between so-called ‘high culture’ and the popular culture. Ellie Anne Duke wrote concerning this relationship: “The composer knew how to capture the agogic accents of rural music and mix them with vivid harmonies and on-target polyphony.”[1]

It is for such reasons that Colombian and Latin American choirs are drawn to his works and want to sing them in concert, since, when listening to them, we find reminiscences of the past and of rural customs.

Why is it important to study Luis Antonio Escobar? He is undoubtedly one of the most well-known composers in our country, as noted by Amparo Ángel: “His music, which is recognized as world-class, is performed in many countries of Latin America and Europe; it is a music that synthesizes the feelings of the Columbian and Latin American peoples and, in an exquisite way, lets you come to understand their sense of life and way of being.”[2]

As Ramón de Zubiría says in the prefatory notes to his La música en Cartagena de indias (Music in Cartagena, Colombia), we find implicit the patriotic emotion that resonates through all his works. As a composer and equally prolific writer, he strives to bring Colombian music out of the shadows: In addition to creating musical scores, editing books and writing essays – among them: La música precolombiana, (Precolumbian Music), La música en Santa Fé de Bogotá (Music in Bogotá, Colombia), La música en Cartagena de indias (Music in Cartagena, Colombia) and La herencia del Quetzal (Heritage of the Quetzal) – he also undertook specific investigations into Afro-American and indigenous cultures, examining their customs, music, rhythms, and liturgies. In ‘Los Indígenas’ (The Natives), an article written in 1956 for the magazine La música en Colombia (Music in Colombia), a publication of the University of Antioquia, Luis Antonio Escobar states:

“Some musicians and historians generally refer to things called ‘pentatonic scales’ such as are typical of our indigenous cultures. This would be equivalent to thinking that the natives somehow unified a system and balanced the sounds. This thesis is incredible since music had to wait thousands of centuries for its melodic classification in the Western world until the emergence of such a brilliant mathematician as Pythagoreas[3].”

In an interview with Amparo Ángel in the article ‘Ecos, contextos y des-conciertos’ (Echoes, Contexts and Dis-concerts),[4] he speaks about the third part of his artistic life, when he had returned to Colombia to undertake important pedagogical work for the Radiodifusora Nacional television network, giving conferences in universities and institutions, and serving as music commentator for the newspapers El Tiempo and El Espectador.

Luis Antonio Escobar highly valued the choral music of Colombia, which is why he organized the university choirs, as founder and president of the student singing clubs. In the same way, to promote that activity, he brought in specialists in singing methodology to teach choral directors from different universities and government entities. With the purpose of bringing favorable attention to the repertoire of the student singers clubs, Luis Antonio also published El libro de Música Polifónica Colombiana (The book of Polyphonic Colombian Music), with works from colonial times through the 20th century, as well as a book on the first Colombian composer of colonial times, José Cascante.

Luis Antonio Escobar’s work as a researcher, particularly on the origins of music in Colombia, made however the greatest impact. When he wrote about music in Cartagena, narrating the events surrounding the arrival of music there, the first musician from the colony, the popular and the folkloric, he makes us take note of the instrumental richness and rhythmic differences, in addition to the anthropological and social connotations of these blends. Luis Antonio Escobar was passionately committed to the investigation and development of all these projects. On this subject, Ramón de Zubiría says in the preface of the book, la Música en Cartagena de indias (Music in Cartagena, Colombia):

“I have written these pages with almost juvenile joy, by surprise, as if it fulfilled an internal demand, with which to seek after my own oxygen or to open wide the window that surveys all the seas and cultures from Cartagena, the Cartagena that has turned four hundred and fifty years old, the one that gave over its virgin beaches to begin producing fruit that in turn will continue fructifying and shaping our own life[5].”

In a 1990 article in the newspaper El Tiempo titled ‘La clave de mi’ (The Key to Me), Luis Antonio Escobar summarized his life in simple terms, speaking of his essence, his roots, describing folklore and customs. The composer of Las Cánticas recounts his beginnings in musical life, making evident the importance of his environment for his growth as a person and a musician, his family, friends, and neighbors (even the town priest) all ready to support him in his initial efforts. This whole story, plus original declarations – “moderate by force, halfway between the scent of a tallow candle when it is snuffed out and a recently burnt corn muffin” – founded in Luis Antonio Escobar great hopes and the staunch decision of continuing his training until he made himself into a composer, one of the most important from Colombia.

But who was the human being Luis Antonio Escobar? As those in his immediate circle say, he was a man who freely shared his knowledge. He was characterized by his affability and by giving happiness to those who surrounded him. Perhaps this is the sense of his first Cántica: “Cántica if I don’t sing I will die from the pain, but with the Cánticas that I sing, my heart is at rest.” With this sentence he sets off twenty musical moments where the composer demonstrates his profound knowledge of music, but through the filter of popular culture, also taking advantage of the opportunity to include in them a dedication to his loved ones.

What is the music’s starting point: Rhythm? Melody? Harmony? His music was the result of being formed and enfolded by the medieval spirit, uplifted with principles and in an era in which, as he himself said, the word was sacred, time was slow, and silence palpable. It was also molded by his first-hand contact with Western music, the teachings of great composers, and the practice of composing in different styles, and by his close-up assessment of different eras. In the Cánticas, melodies and harmonies are impregnated with different historical moments: Renaissance, Baroque, Classic, Romantic and Neoclassical, and at the same time, with the rhythms and prosody of folksong. For that reason the Cánticas utilize diverse rhythms, amalgamated bars, asymmetric bars, always with the intention that that the metric should give an agogic effect without losing its natural form.

While recognizing and respecting the opinion of one of Columbia’s greatest musicians, Luis Antonio Escobar affirmed his hatred of “rock and roll”, in a clearly radical posture, because it seemed to him backward, commercial and violent; but if we analyze the implicit social value of this musical genre, it was not only the music that attracted multitudes from the 1950s on, it was in effect a lifestyle that found in youthful rebellion the way to respond to the weariness caused by repression and coercion in a romantic search for freedom. Luis Antonio Escobar’s own words explain his position:

“We prefer all kinds of information, information that may be important, but not so much so as to leave aside the study of what we really are. All study and information should have as a reference the examination of ourselves. We still live with the yoke of servitude on the neck of our spirit, and we only use our rebelliousness and arrogance to defend, with greater or lesser capacity, theories and interests that are more in tune with other peoples or nations.”[6]

Nevertheless, we should understand that all artists take sides. His concern was in finding the relationships between what is called high culture and popular culture. His musical works move in diverse genres, formats and styles – operatic, vocal and instrumental; for orchestra, piano, and chorus. But the texts of the Cánticas are taken from popular culture, folklore of the purest kind. Thus in one to them, a warning is given, “Forgive me if these songs seem bad, because I sing them the way they emerge.” (Cántica no. 4). This overlapping is unacceptable for those purists who, even now in the 21st century, continue seeing high culture as a pedestal to which anyone who aspires to be called a musician must ascend.

But Luis Antonio Escobar’s nostalgia went further: Although his academic training was complete, he continued growing and he admired the fineness and charm of the peasant farmers sporting espadrilles and dirty fingernails, who recited when finishing their tasks, “The night comes lowering by the hills of the balcony and, fills with sadness the mountain, ranch and heart.”[7] For example, he puts his feelings in high relief and declares his love, emphasizing that other time which is now his longed-for natural surroundings. In folksong form he says, “If the bramble doesn’t entangle me, if the liana doesn’t enwrap me, I will marry you if death doesn’t take me.” (Cántica number 6).

But this is a man who also created ballets for the greatest dancers in the world (Ballet Theatre of New York with choreography by George Ballanchine) and who shared the stage with musicians of the caliber of Andrés Segovia, Aaron Copland and Carlos Chávez, among others. Yet he deeply missed his friends, hence the dedications of his songs. In one he inquires of his great friend Gustavo Yepes, “When I wait you don’t come, when you come there is no place, this is how we pass the time and this is how it will pass us by.” (Cántica 11). The query finishes in a recrimination: “Don’t tell me some other day, because this life lasts only a second and after I die what does it matter to me if the world exists?” (Cántica 11).

This same sensitivity at a very young age also allowed him to be moved listening to Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 and Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli, one of the most famous polyphonic works of the Renaissance. His familiarity with other cultures, the ability to understand other musicians, and the influence of other great composers, never moved Luis Antonio Escobar away from his proposed goal, to compose drawing from folklore. On the contrary, to know so well what the National Schools did in Romanticism, including knowing that from 1742, as Hamel and Hirliman say in their Encyclopedia (Vol. I, p. 275), summaries of popular Scottish, Welsh and Irish melodies had already appeared in England and that in 1793, George Thompson incorporated these melodies into cultured music, when ordering the harmonization of the great composers of the time – a dynamic linked to the thought of that historical moment:

“The discovery of the traditional values of the historical past and, with it, as much as in politics, in the spiritual as in the artistic, the formation of a new national conscience with the premise, a new eruption of the national essence.”[8]

The popular melodic spirit in cultured music had already borne fruit from the 18th century: Beethoven used popular Russian melodies in his Quartets op. 59 (variations on a theme); Schubert made use of melodies and rhythms from Hungarian folklore for an entire series of compositions; and the Hungarian nationalists, among them Béla Bartók, and the Russians, Balakirev, Cui, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky, as well as the Mexican composers Chávez, Revueltas and Ponce must all be mentioned here.

These were palpable things which helped Luis Antonio Escobar to reassert his principles. For this reason, the Cánticas, the ‘bambuquerias’, the madrigals, the rural cantatas for chorus and orchestra, and the cantatas of Colombian singers all share a common theme and particular rhythmic pulse. His own words reflect those roots with more clarity:

“When we speak of true folklore, we contemplate the first drawings of men, the ambrosial melodies resonate, rondels and music of medieval poets, those praised by our blacks of the Pacific or the out-of-tune scream of the guabina that tints the soul and the cheeks of our ingenuous peasants red, are songs that, in one way or another, lock essences of Olmecan sculpture, gestures of severe figures like the ones on Easter Island, songs that retain the vibrant wave of Mayan architecture or the subtle symmetry and fine color of the cloth of Paracas. Everything that makes the man is from his interior, it is their own sculpture, and nothing better than his own song.”[9]

Luis Antonio Escobar was definitely a man in love – in love with life, with people, with the theater of pantomime and of Quevedo, Cervantes and Shakespeare. As he said in the article in El Tiempo, ‘la clave de mi’ (The key to me): “Men of synthesis, of feelings, towns and eras”. And speaking of feelings, Cántica no. 5 is a sketch of the man of feelings, the romantic man. It is poetry of a high level, it is Quevedo, it is Cervantes, Machado, Silva, Haine. “You are a gold nugget and a drawn pearl and you are the star that lights the dawn, you are as the blond wheat selected grain by grain, you are you, the most beautiful that my eyes have ever seen, you are as the blond wheat selected grain by grain, you are you the most beautiful that will ever be born in the world” (Cántica no. 5). In contrast, Cántica no. 6 is a folksong with a more picaresque style, making reference to the texts used in the bambuco, pasillo and guabina, to those texts of the mountain folk, ingenuous and sincere but shy, of double meaning. “Come here and get a little bit closer to he who wants to give you a kiss and a tight hug; last night I had a dream and in the dream it seemed that your mouth kissed me and I slept in your arms.” (Cántica no. 6). In Cántica no. 7 the double meaning is more evident, especially in the use of words like ‘aigre’ that are so characteristic of the highland regions of Cundinamarca and Boyacá: “I fell in love with the air of the air of a woman, as the woman is air, in the air I stay.” (Cántica no. 7). There remains only a slight suspicion regarding the meaning of the text. But it is possible to make conjectures, as a single word ‘aigre’ proffers many interpretations, as poetry, or value judgments, and so on. Amid such picaresque texts it is possible for that type of uncertainty to exist.

The Cánticas were certainly created by a man moved by emotion and sensitivity, not only in the beginning but throughout the course of his life. Such is the case in Cántica no. 17, where the text states: “Life passes soon like the waters of the river and it takes in its current her thoughts and mine.” The same work reconfirms these words: “Thought, stay quiet; at least stop tormenting me for a moment so I can speak calmly.”

As for musical analysis of the Cánticas, we paraphrase here a text by James Manheim, one of the members of the US chorus America’s Vocal Ensemble. They recorded the Cánticas in 1982, undertaken as an exchange project between North America and Latin America, a matter of much interest for the new century. These Cánticas and madrigals were transformed into a singular work premiered at a performance in 1983. For Manheim, the Cánticas were not thought of by the composer as a homogeneous whole; number one of the sequence could just as well be followed by number five, and so on. And although they are of several sizes and degrees of harmonic colors, they are as simple as the madrigals and with many parallel harmonies. Manheim states:

“Luis Antonio Escobar does not have the hypersimplicity of Ariel Ramírez, nor the nationalism of Carlos Chávez and neither the ‘Bartokianos’ experiments of Alberto Ginastera. Luis Antonio keeps the squared forms of the texts from his roots and develops a flexible harmony, language that expresses the content in detail.”[10]

This seems to be a unique recording and the chorus is well qualified to examine globally the real sense of the rural folksongs, so closely connected as they are to folklore and the daily life of that region. These are: “concise and absorbing pieces: anyone who likes the choral music of America, or is looking for something attainable, will be able to obtain it from these, and will end up knowing them.”

Musical analysis of the Cánticas

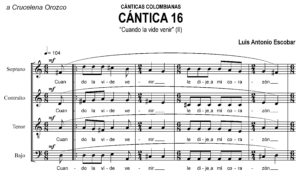

One general feature of the Cánticas is that most are of a homophonic texture. Cánticas nos. 6 and 2 have particular features: Cántica 6 has piano accompaniment; Cántica 2 begins with a slight indication of polyphony before becoming transformed into homophonic texture; it also shares the beginning of the text with Cánticas 16 and 22. “When I saw her coming, I told my heart what a beautiful pebble she was to trip over.” The character of the three Cánticas is different; no. 2 is marked Presto marcato, number 16 is quarter note = 104, is more lyrical and lighter, and number 22 is marked Allegro; nos. 2 and 22 begin in 3/4 time, and no. 16 in 6/8 time with an anacrusis.

(Click on the images to download the full score)

The following chart provides a general overview of the Cánticas:

|

Cánticas |

C.1 ‘Cánticas si no cantara’ |

C.2 ’Cuando la vide venir’ |

C.4 ‘Me perdonan estas coplas’ |

C.5 ‘Eres un granito de oro’ |

C.6 ‘Hacete de para acá’ |

C.7 ‘Yo me enamoré del Aigre’ |

|

|

Texture |

Homophony |

Polyphony and Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

|

|

Register |

Eighth |

Eighth |

Twelfth |

Seventh |

Seventh |

Ninth |

|

|

Tonality |

G |

Opening Gm and closing A flat |

Opening in F and closing in C |

Initial in Am closing E7 |

Opening in Gm7 and closing Gm |

Opening in Am closing in C |

|

|

Dedication |

Joaquín Piñeros C. |

Alfred y E.Greenfield |

Elenita Biemann |

Helena Grau |

Amalia Samper |

Clorinda Zea |

|

|

Type of ensemble |

Male Chorus |

Male Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

|

|

Style |

Romantic |

Renaissance |

Baroque |

Romantic |

Neoclassical |

Neoclassical |

|

|

Type of text |

Poetic |

Folkloric |

Poetic |

Poetic |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

|

|

Form |

A—A1 |

Introduction A—A1–A2 |

A–A1–A2 |

Introduction A–A1—B |

Interlude chorus A-A1-A2 |

A–B |

|

|

Ranges |

25 |

42 |

31 |

35 |

68 |

5 |

|

|

Duration |

2:53 |

2:55 |

0:31 |

1:31 |

2:40 |

1:04 |

|

|

C.8 ‘El de sombrerito e jipa’ |

C.9 ‘Dende aquí te toy mirando’ |

C.10 ‘Si nos hemos de morir’ |

C.11 ‘Cuando espero no venís’ |

C.12 ‘Me topé con una niña’ |

C.14 ‘La rosa nació en la arena’ |

C.15 ‘Me perdonan estas coplas’ (II) |

|

|

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

|

|

Tenth |

Eighth |

Eighth |

Eighth |

Seventh |

Ninth |

Seventh |

|

|

Opens in G and closes in E flat |

Opens in Dm and closes in C |

Opens in Bm and closes in F |

Opens in F and closes in C |

Opens in Am and closes in Dm |

Opens in Dm and closes in G |

F |

|

|

Maria Cristina Sánchez |

Ellie Anne Duque |

Eduardo Mendoza |

Gustavo Yepes |

Rodolfo Pérez |

Titina y Jaime |

Rito Antonio Mantilla |

|

|

Womens Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

|

|

Neoclassical |

Romantic |

Neoclassical |

Romantic |

Renaissance |

Romantic |

Renaissance |

|

|

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

|

|

Intro A–Intro B–C |

A–B– c–B1 |

A–B |

Introduction A –B |

A–B |

A–B |

Intro and A intro B and coda |

|

|

33 |

17 |

20 |

25 |

33 |

20 |

55 |

|

|

0:55 |

2:21 |

1:08 |

1:41 |

0:41 |

1:45 |

2:40 |

|

|

C.16 ‘Cuando la vide venir’ (II) |

C.17 ‘La vida se pasa pronto’ |

C.18 ‘Lucero de la mañana’ I |

C.19 ‘Lucero de la mañana’ (II) |

C.20 ‘Te arrullo en la cuna’ |

C.21 ‘De tres amores que tengo’ |

C.22 ‘Cuando la vide venir’ (III) |

|

|

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

Homophony |

|

|

Ninth |

Eighth |

Eighth |

Ninth |

Ninth |

Seventh |

Ninth |

|

|

Opens in D and closes in A |

Opens in Dm and closes in C |

Opens in Dm and closes in F |

Opens in D and closes in A |

Opens in C and closes in F |

Opens in Dm and closes in D |

Initial in D and closes in E flat |

|

|

Crucelena Orozco |

Maria Cristina Lanao |

Amparo Ángel |

Amparo Ángel |

Diana Vesga Sánchez |

Nelly Vuksic |

Nelly |

|

|

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Mixed Chorus |

Feminine Chorus |

|

|

Neoclassical |

Neoclassical |

Renaissance |

Neoclassical |

Renaissance |

Neoclassical |

Neoclassical |

|

|

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

Poetic |

Poetic |

Poetic |

Folkloric |

Folkloric |

|

|

A–A1 |

A–B |

Introdu y A–A1 |

A–A1 |

Intro y A–A1–A2 |

A–B |

Intro y A–B—C |

|

|

16 |

13 |

10 |

16 |

17 |

27 |

31 |

|

|

0:41 |

1:41 |

0:46 |

0:41 |

3:21 |

2:05 |

2:08 |

|

Epilogue

Luis Antonio Escobar was a Colombian composer of great transcendence at both the national and international levels. The history of his achievements in his own country and the outside world demonstrates how his music has shared the stage with that of world-class composers such as Aaron Copland, Andrés Segovia and Carlos Chávez. His investigations into indigenous Colombian culture, his thesis of pentatonic scales as typical of our indigenous cultures, prove that is was one of the country’s most renowned figures.

Of his choral works, Cánticas Colombianas, published in 2011 by the Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, stands out. From a total of 22 Cánticas, 20 remain extant. (Cánticas nos. 3 and 13 are lost.) These twenty moments of music and poetry, or popular sayings, find their roots in folklore. Studying the Cánticas, the composer’s incentive for writing them is palpable, namely the healthy relationship he enjoyed with the people to whom they are dedicated. From that perspective, the Cánticas were conceived on a very human scale. The attractiveness of the texts, their rhythmic variety and articulation, the composer’s respect for the prose, content of conflicting feelings, and the composer’s treatment of tessiture, – all these transform the Cánticas into a most interesting collection of music.

[1] Article published in the newspaper El Tiempo, August 5. Taken from the magazine Credencial Historia, No. 120, December, 1999.

[2] http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/musica/blaaaudio/compo/escobar/indice.htm

[3] ESCOBAR, L. La música en Colombia, “Los Indígenas” Emisora cultural Universidad de Antioquia, Agosto 1956, publicación mensual, numero 81, Pg. 1—6.

[4] Research project at Universidad EAFIT-2003 Gil Araque, Fernando, Ecos Contextos y Desconciertos.

[5] http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/musica/muscar/indice.htm

[6] Prelude to La música en Cartagena de indias by Luis Antonio Escobar (1985).

[7] ESCOBAR L.A.: La Clave De Mí – Archivo – Archivo Digital de Noticias de Colombia y el Mundo desde 1_990 – eltiempo_com.mh)

[8] Enciclopedia de la muisca, Hamel y Hurliman, tomo I, pg.275—276.

[9] Prelude to La música en Cartagena de indias by Luis Antonio Escobar (1985).

[10] http://www.answers.com/topic/luis-antonio-escobar-Cánticas-y-madrigales

[11] http://www.answers.com/topic/luis-antonio-escobar-Cánticas-y-madrigales

Select bibliography

F. Hamel, and M. Hùrliman, (1959) Enciclopedia de la Música, Traducción y adaptación del Dr. Otto Mayer, México, Vol. I, ‘Las escuelas nacionales’, (p. 275-276).

A. Pardo, (1966). La cultura musical en Colombia. Historia extensa de Colombia, Vol. 6, Bogotá: ediciones Lerner.

J. Perdomo, (1980). Historia de la música en Colombia, Bogotá: Ed. Plaza y Janes.

E. Bermudez, (1962). Historia de la Música en santa fe de Bogotá, Ed. carpel, Bogotá Colombia.

L. Escobar, (1985) La música en Cartagena de Indias. Derechos Reservados del Autor, Final de la impresión 1 de Septiembre de 1985, Taller intergráfica limitada, Diseño Luis Antonio escobar Amparo Ángel.

L. Escobar, (1987) La música en Santafé de Bogotá, Editado por la lotería de Cundinamarca, Impresión Rigoberto Sepúlveda, Diagramación Ángel, Derechos reservados del Autor. Final de la impresión 6 de Agosto de 1987.

― (1985). La Música Precolombina, Editado por la Universidad Central, Diagramación y corrección de pruebas: Amparo Ángel, Derechos reservados del autor. Final de la impresión 30 de Noviembre de 1985.

― (1992). La herencia del Quetzal, Ed. Santa Fe de Bogotá, Ángel Cultural Editores.

― La Clave De Mí, Archivo Digital de Noticias de Colombia y el Mundo desde 1992, Publicación el tiempo.com.mh, sección otros, Fecha de publicación 1 de Febrero de 1992. Autor Camándula.

― Canticas Colombianas, Fondo editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2011. Editor, Andrés Posada Saldarriaga, Digitación, Julián Botero Vargas.

― L. Escobar, La música en Colombia, Los Indígenas, Emisora cultural Universidad de Antioquia, Agosto 1956 publicación mensual- numero 81 Pg. 1—6.

http://www.lablaa.org/blaavirtual/musica/blaaaudio/compo/escobar/indice.htm

http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/musica/blaaaudio/compo/escobar/indice.htm

http://www.answers.com/topic/luis-antonio-escobar-Cánticas-y-madrigales

Translated from the Spanish by David Cowder and Anita Shaperd

Revised & copy edited by Anita Shaperd (USA) and Gillian Forlivesi Heywood (Italy)

Edited by Graham Lack