Forging choral composers

Alberto Grau, composer, conductor, pedagogue, Venezuela

The principal purpose of a choral composition method is to help young composers find new paths and languages that allow them to create interesting and enjoyable collaborative works and, through them, learn to love musical activity rather than spend long periods in academic study. For this article, I have selected some passages from my book, ‘La Forja del Compositor’ (The Forging of the Composer), the content of which I consider essential for the training of composers.

Of Poetry and Music

Poetry and music, more than merely an alliance of artistic languages, represent perhaps one and the same language. Speaking is already a form of singing because, when we speak, we emit sounds accompanied by harmonics that define our timbre and our language, whatever it may be. Speaking always draws melodic lines that emphasize admiration or express doubt in a question. But even the serene narrative includes melody and rhythm. From moment to moment, we are protagonists of our own essential opera. Each time we produce our words, we sing.

What does poetry tell us? It transmits expressive nuclei of information, intelligence, sensitivity and emotion.

The composer finds in poetry the root of what he or she wishes to communicate to us musically, be it Li Taipó, the great romantic poet of the Tang dynasty, revealed to us by Gustav Mahler, or Federico García Lorca in the music of George Crumb.

Music has served on many occasions to rediscover or elevate the work of a poet who is no longer widely read. Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann as well as Hugo Wolf, in the sphere of Germanic culture, have reminded us of poems by Eduard Mörike, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Rückert.

Every musician will find in poetry a source of inspiration, insinuation and suggestion that provides for a new twist to the poem and a means for pouring into and imbuing a score with the music behind the poetry.

Text and Rhythm

If music is accompanied by text, as is usually the case in choral music, the composer must take the greatest care to observe the relationship between the text and the rhythm.

It is common to observe that the energy that leads to climactic points is derived from the word. Once the poetry is learned, it will be necessary to address the rhythm through which the text is transmitted. It will be necessary to find the proper phrasal rhythms in order to be able to project the message in the most accurate way at the right time.

A theory of tonal ideas, their consequences and a rational system of notation must be based primarily on phenomena of a rhythmic order. Languages or spoken manifestations, whether of primitive or learned origins, always contain within themselves a rhythmic structure. For this reason, the indisputable connection between the text and the rhythm is more than defined and verified because the word and its spiritual content are what can best contribute to sung music.

Rhythmic Units are rhythmically indivisible groups of two or three notes. Understanding this point in relation to rhythmic organization is fundamental to the education of the composer.

When a series of regular articulations reaches our consciousness, these undergo their first developmental process.

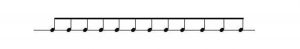

Consider the following example where we see a group of rhythmically incoherent notes:

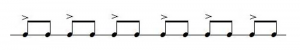

The mind begins to create order and, in this interest, introduce accents, which permit it the domain of auditory sensations. The accentuation, every two or three notes, will be formed in the medium-speed register at approximately a rate of 50 or 60 beats per second. So, the previous example could look like this:

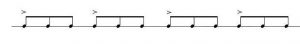

Or also like this:

According to this first operation of mental arrangement, the individual notes of the series, which are initially undifferentiated, also acquire a hierarchy of intensity in a natural way. Some take on more gravity while, conversely, others retire. Both Emphasis and release are relative. No note can have weight if it does not have other neighboring notes to support it. The association of these qualities is the foundation of all perceptions of a musical nature.

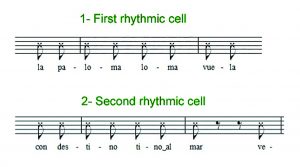

Examples of Rhythmic Formulas created according to text.

The Dove

Poem: Eduardo Polo (1938-2008)

Music: Alberto Grau (1937)

Exercise:

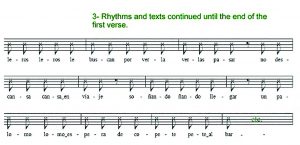

With small changes in rhythm, create rhythmic formulas with the following six verses:

| La paloma vuela | The dove flies |

| con destino tino al mar | bound for the sea |

| veleros leros le buscan | sailboats look for her |

| por verla verla pasar. | to see her pass by. |

| No descansa cansa en viaje | She does not rest in her journey |

| soñando ñando llegar | dreaming of her arrival |

| un palomo lomo espera | a dove awaits |

| de copete pete albar. | with his white crest. |

| Con chaleco leco fino | With fine waistcoat |

| vestido tido de frac | and tailcoat dress |

| cubierto bierto de joyas | covered in jewels |

| en la iglesia glesia está | in the church is |

| contando tanto las horas | counting the hours |

| para para se casar. | to be married. |

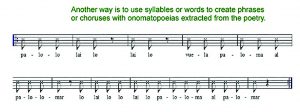

These rhythms can be created with cells taken from each of the poetic verses, or per complete stanzas:

We could also add a eurythmic formula to accompany this melody of two notes:

(Musical examples pages 38-39-40, from the book, La Forja del Compositor by Alberto Grau)

Types of Choirs

It is worth remembering that, when talking about good choirs, existing and in general, the term refers to human groups potentially composed of amateurs rather than professional musicians, whether they are members of mixed choirs, equal voices choirs, children’s or youth choirs or professional choirs. For example, a choir representing a poor neighborhood with scarce infrastructure and logistical resources has as much merit as the choral group that works under the best available circumstances. What matters is the social and cultural result they obtain by taking advantage of the means at their disposal. Establishing a definition of a ‘good choir’ is as difficult as determining, through any written framework, the essence of another reality. The satisfactory condition of a choir is the result of a sum of elements that lead to subjectivity of appreciation but, like the aesthetic values of a musical work itself, are not likely to be quantified. It should not be forgotten that, with the addition of a respectable number of positive subjective conditions, the result, precisely because it is derived from an increased number of observations, tends to become more and more objective.

These are some of the ideas that, as a composer, I like to share with my students and thus encourage them, based on my experience, to be creators of new sounds and rhythmic combinations that encourage young singers to participate with joy, humor and enthusiasm in the wonderful world of choral singing.

Distinguished composer and teacher, Alberto Grau (Vic, Catalonia-Spain 1937), has earned a place of honor among the best contemporary musicians in Venezuela. Known for his career as a Choral Director, Alberto Grau has, however, become one of the leading figures in choral composition in Latin America, and many of his works have been published by houses in the USA and Europe. He won the José Angel Montero National Music Award three times (1967, 1983, 1987) and other important international awards. He was recognized in 2014 with the Lifetime Achievement Choral Award by the International Federation for Choral Music (IFCM). In 1967, he founded the Schola Cantorum de Venezuela and won First Prize in the 1974 International Competition Guido D’Arezzo in Italy. More than 30 recordings evidence his fine musicality and extensive knowledge of the international choral repertoire. He was also the founding director of the Orfeón Universitario Simón Bolívar and the Ave Fenix Choir, a member of the Board of Directors of the State Foundation for Children and Youth Orchestras of Venezuela (El Sistema), the Musical Director for the Teresa Carreño Theater in Caracas, the IFCM Vice-president for Latin America and an advisor and professor for the CAF Social Action through Music Program. For more than 35 years he was a professor of Choral Conducting at the University Institute of Musical Studies and at the Simón Bolívar University and also a director of El Sistema choral-orchestral productions. He has been invited to many important conferences and festivals, including ACDA Conventions, World Choir Symposia and the Europa and America Cantat Festivals. He is currently the permanent advisor and composer-in-residence for the Schola Cantorum Foundation of Venezuela Little Singers Program and continually receives new commissions from all over the world. Email: mariaguinand@gmail.com

Distinguished composer and teacher, Alberto Grau (Vic, Catalonia-Spain 1937), has earned a place of honor among the best contemporary musicians in Venezuela. Known for his career as a Choral Director, Alberto Grau has, however, become one of the leading figures in choral composition in Latin America, and many of his works have been published by houses in the USA and Europe. He won the José Angel Montero National Music Award three times (1967, 1983, 1987) and other important international awards. He was recognized in 2014 with the Lifetime Achievement Choral Award by the International Federation for Choral Music (IFCM). In 1967, he founded the Schola Cantorum de Venezuela and won First Prize in the 1974 International Competition Guido D’Arezzo in Italy. More than 30 recordings evidence his fine musicality and extensive knowledge of the international choral repertoire. He was also the founding director of the Orfeón Universitario Simón Bolívar and the Ave Fenix Choir, a member of the Board of Directors of the State Foundation for Children and Youth Orchestras of Venezuela (El Sistema), the Musical Director for the Teresa Carreño Theater in Caracas, the IFCM Vice-president for Latin America and an advisor and professor for the CAF Social Action through Music Program. For more than 35 years he was a professor of Choral Conducting at the University Institute of Musical Studies and at the Simón Bolívar University and also a director of El Sistema choral-orchestral productions. He has been invited to many important conferences and festivals, including ACDA Conventions, World Choir Symposia and the Europa and America Cantat Festivals. He is currently the permanent advisor and composer-in-residence for the Schola Cantorum Foundation of Venezuela Little Singers Program and continually receives new commissions from all over the world. Email: mariaguinand@gmail.com

Translated by Joel Hageman, USA