A Glimpse at David Brunner’s Choral Music for Advanced Women

By Kelly Miller

David L. Brunner (b. 1953) is one of the most prolific choral composers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. He is an actively performed and commissioned choral composer in the United States; as of 2015, he has composed over 150 choral works. Of his 150 works, 67 are listed by publishers and his website under the heading of treble choir, a broad vocal descriptor referring to the female and unchanged male voice. Regardless of this label, most of Brunner’s treble pieces are eminently suitable for women’s choir, a mature ensemble of advanced high school, college, or community women, and 22 of his works target this group. This is due in part to mature texts, neo-Romantic melodies, and experimentation with tonalities outside of the Western choral art tradition. This article will take a brief look at how Brunner began composing and focus on his text selection, melodic elements, harmonic language, accompaniments, vocal range, timbre, choral texture, and score markings, especially for advanced women.

The Beginning

Brunner’s journey as a composer transpired organically, with his early treble voice experiences shaping his compositional prowess. Following his undergraduate graduation in 1975, Brunner was asked to write a treble piece for Illinois Wesleyan’s upcoming Christmas concert. The tune, titled Little Baby, Did You Know, was written for IWU’s Women’s Chorus, directed by Dr. Sammy Scifres.[1] After Wesleyan, Brunner began arranging music for his own choirs to meet their varying requirements. He composed as needed, but Doreen Rao helped to create a national audience for his works. Brunner states, “I think she [Rao], more than anybody, is responsible for fostering this whole thing [his composition career]. How I even started to do this, or even thought that I could do this, or should do this, or that it somehow makes me feel good to do this. She really was instrumental early on in that.”[2]

Rao immediately connected to Brunner’s music. When she started to develop the Choral Music Experience series with Boosey & Hawkes in 1986, she encouraged him to submit his choral music for publication. CME choral classics like Hold Fast Your Dreams for treble voices and O Music for SATB choir, cello, and piano began to define him as a gifted composer whose love of great poetry and sensitivity to the voice combined to distinguish his writing in the United States and abroad.

With experience comes a freedom to take more risks. As his compositions evolve, Brunner has begun choosing mature texts that are sensual and provocative. He has become more interested in music outside of the Western classical art tradition and in experimenting with the unfamiliar. He has written for diverse instruments and asked singers to try new vocal styles. Brunner finds himself being drawn to music with a message, music that makes a difference in the lives of the singers and audience.

Text Selection

Text selection is the most important element of Brunner’s compositional process. Brunner’s approach to selecting text contains elements of diversity: time period, age, culture, metric construction, and ‘how’ and ‘why’ he chooses to change a text in its musical setting. He contends that conductors never really experience the music until they understand the poem – its content and meaning as well as the architecture, rhythm, and rhyme. Brunner argues, “The basic impulse for the composition of vocal music is the text. Vocal music is text! Since music and words are closely related, the texts must be of literary integrity and value. This integrity and value rests more in the quality of the verse than in the sophistication, be it sonnet or limerick.”[3] His rigorous approach to text selection guides his use and treatment of diverse literature that spans a variety of time periods, poets, and metric constructs.

In his music for women’s choirs, he chooses poets both past (Saint Francis of Assisi, Mirabai, John Davies, John Newton, William Blake, and e. e. cummings) and present (William Austin, Janet Lewis, Seamus Heaney, and Ann Ziety). He features the texts of sixteen female poets, including the 20th-century Canadian poet Margaret Atwood, American Louise Driscoll, born in the last third of the 19th century, and Mirabai from 16th-century India.

He seldom omits words but has, on occasion, combined texts or written his own. For example, the inspiration for All Thy Gifts of Love originated as a verse from the Hunger Fund Committee of the Diocese of Huron that he received as a Christmas greeting. He incorporated this fragment with the words of a prayer by the Rev. Galen Russell. In Simple Boat, for women’s and mixed choir, an Irish fisherman’s prayer depicts the plight of the child with the adults of the community responding with two passages from the Buddhist text The Way of the Bodhisattva.

Melodic Elements

One of the most appealing qualities of Brunner’s music is his melodic writing. He creates beautiful tunes that bring poetry to life. Lynn Gackle states, “It’s difficult to discuss his music without discussing his gift for melody.” She adds, “His music has a definite ability to encapsulate the words within a lush melody.” [4] Emily Ellsworth agrees: “[Brunner’s melodies are]…very singable – making the most of the singer’s ability to spin a musical line.”[5] His melodies linger in the memories of both audience and performer.

Brunner’s melodies reflect his skill at reinforcing text stress with pitch and length of syllables. He seeks to create a line that “sing[s] like it speaks.”[6] He desires organic word emphasis and speech rhythm to create a delineation of text, and employs rhythm, melodic shape, tempo changes, alternating meters, and interlacing stressed and unstressed syllables to emphasize natural word accentuation.

Harmonic Language

Another compositional feature of Brunner’s works is the harmonic language with which he supports his melodies; it is both diatonic and tonal. Distinctive pieces that remain in one key are Winter Changes, Hold Fast Your Dreams, Home, If I Could Fly, and A Song for Every Child. Brunner is not afraid to utilize dissonances. He enjoys writing music that deviates from a tonal center, as seen in This Magicker and Star Giver. In The Circles of Our Lives, Isn’t That Something, Radiant Sister of the Day, and Rain Stick, he favors a centric yet modern conception of tonality involving chromaticism and non-chord tones that allow him to stray from the established key. Sir Brother Sun and Southern Gals are examples of pieces containing multiple modulations.

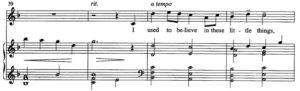

A typical feature in both melodic and harmonic language is his employment of extended intervals or, ‘Brunnerian Leaps.’ Ninths and elevenths are Brunner’s leading choices, as seen with the C4 to D5 in m. 40 to m. 41 (Figure 1) and the D4 to E5 in m. 5 to m. 6 of Figure 2. Both examples demonstrate mindful voice leading and a harmonic structure supporting the melodic intervals.

Figure 1 Winter Changes, mm. 39-42

Figure 2 Isn’t That Something?, mm. 4-7

A more recent and exciting element in Brunner’s harmonic language is his employment of non-Western sonorities. For All I Was Doing Was Breathing, Brunner researched Indian music but began composing without a specific mode or scale in mind; an E F G# A B C D# tonality emerged as the piece developed. This pattern of intervals resembles those of the Bhairav Thaat Raag, C Db E F G Ab B, a collection of pitches used in the classical music of north India.[7] Indian thaats are not fixed and may begin on any pitch.[8]

Accompaniments

Almost all of Brunner’s pieces are written with piano accompaniment. The piano varies in the complexity of the writing and difficulty of performance. He seldom writes purely unaccompanied pieces. Several are available in brass, chamber, and full orchestra editions. Many of his works contain parts for obbligato instruments such as flute, oboe, and cello. Other pieces contain a myriad of percussion instruments ranging from finger cymbals and rain sticks to tabla. His piano accompaniments reflect an accomplished pianist; his accompaniments can be challenging. As seen in Figures 1 and 2, they harmonically reinforce his melodies. An example of his pianistic features is the rhythmic writing of two against three. In m. 47 (Figure 3) of Star Giver, the choir sings crotchet triplets as the right hand plays quaver, and the left hand performs quaver triplets.

Figure 3 Star Giver, mm. 47-50

The untraditional accompaniment of All I Was Doing Was Breathing sets it apart from all of Brunner’s other music. Choral musicians accustomed to piano or a cappella songs are challenged during the first rehearsals with cello. It is an equal partner with the voices and shares the melodic material at the beginning of the work, taking over the melody as a solo in mm. 11-19 (Figure 4). The cello then settles into a supportive role at m. 19, where it provides stability for intonation.

Figure 4 All I Was Doing Was Breathing, mm. 1-21

Vocal Range

Brunner maximizes the full vocal range of adult women. His melodies tend to be very fluid, full-voice, and full-range melodies. Wide vocal range and tessitura often speak to the difficulty of a work. The soprano parts are inclined to run between C4 – G5, and the altos are apt to be within G3 – D5. The following Alto II part of All I Was Doing Was Breathing rarely enters the staff of the treble clef. The depth of this range (Figure 5) may be challenging for younger choirs, but it intensifies the sound when performed by a skilled ensemble.

Figure 5 All I Was Doing Was Breathing, mm. 149-158

Timbre

With his exceptional understanding of the female voice, Brunner challenges advanced women’s choirs by calling for a wide spectrum of vocal colors contingent upon vowel shape, age of the voices, tone, range, dynamics, tessitura, texture, and additional descriptions located in the music. Sandra Snow has commissioned and performed his music for over 20 years, with choirs ranging in age from child to adult. In an August 2009 interview, Snow spoke of his ability to understand the treble voice in relation to timbre.

I think it’s his conceptualization of treble instrument, of what colors are available to the treble instrument that is so interesting. It’s not a matter of range and tessitura purely; it has much more to do with the shades of color. I think the instrument he writes most beautifully for is the cello – that rich, gorgeous sonority of the cello. Brunner loves and uses it often. He’s simply taken that color palette and made it an expectation of the treble voice we see in his music. In that way, it feels very terrific to sing. It’s not just the ups and downs, or the leaps, or the way he approaches the melodic line. The color is dictated by what he writes into the score, which is a wider palette than maybe some are accustomed to hear.[9]

Choral Texture

The texture of Brunner’s choral works marks another signature element of his music. In his music for women’s voices, he writes mostly in a homophonic texture. He weaves in single lines of melody, vacillating from voice to voice. He rarely crosses the vocal parts. The voicing for his advanced women’s music ranges from unison to multiple soprano-alto configurations. No matter how similar the construction, the texture of his works varies with each piece.

Score Markings

Brunner gives specific direction with score markings, clearly communicating his thoughts on tempo, dynamics, and articulations. He begins most works with a metronome marking and a descriptor: Italian or English terms, or a phrase like “with a feeling of two beats to a measure.” He believes that tempo should be fluid and may need to change pace numerous times within a piece to express the text.[10] Of interest is how often and where he chooses to incorporate the subtleties of accelerando and ritardando, giving the conductor some flexibility. For example, the piano introduction of The Singing Will Never Be Done contains a tempo change in each of the first seven measures, and an additional 23 tempo markings are indicated throughout the score. Brunner exploits the widest spectrum in both vocal and instrumental amplitude, creating dynamic contrast. He enhances text stress with slur, tenuto, and accent articulations.

Summary

David Brunner has the ability to choose strong text and set it to a beautiful melody. He artfully selects evocative texts that speak to the emotional sensitivities and sophistication of adult women. It may be surmised that he has the ability to tap into these elements through his understanding of the mature female voice and draw out the expressive possibilities of a choir. Advanced singers appreciate the challenge of performing his music.

While evolving as a composer, Brunner has advocated for quality repertoire that makes a difference in singers’ lives. He finds himself drawn to music with a message, and in 2011 wrote a piece for Habitat for Humanity. “Any conductor new to women’s/treble voices would be well served by exploring David Brunner’s music. It is vocally, intellectually, and emotionally gratifying for the treble voice of all ages,”[11] states Emily Ellsworth. When compositional catalyst Doreen Rao was asked to describe how she has seen Brunner’s compositions evolve, she replied, “Continuously. A direct reflection on the composer’s character and life choices.”[12]

Edited by Karen Bradberry, Australia

[1] Interview, author and David Brunner, 11 July 2009 (Orlando, Florida).

[2] Interview, author and David Brunner, 11 July 2009 (Orlando, Florida).

[3] David Brunner, “Choral Repertoire: A Director’s Checklist,” Music Educators Journal 79, no. 1 (1992), 32.

[4] Interview, author and Lynn Gackle, 24 March 2010 (by email).

[5] Interview, author and Emily Ellsworth, 9 April 2010 (by email).

[6] Interview, author and David Brunner, 11 July 2009 (Orlando, Florida).

[7] Walter Kaufmann, The Ragas of North India (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1968), 233.

[8] Catherine Schmidt-Jones, “Indian Classical Music: Tuning and Ragas,” http://cnx.org/content/m12459/1.10/ (accessed 4 May 2010).

[9] Interview, author and Sandra Snow, 4 August 2009 (East Lansing, Michigan).

[10] Interview, author and David Brunner, 11 July 2009 (Orlando, Florida).

[11] Interview with author and Emily Ellsworth, 9 April 2010 (by email).

[12] Interview, author and Doreen Rao, 2 February 2010 (by email).