Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) The violent gentleness of a mathematical-musical revolution

Isabelle Métrope, managing editor of the International Choral Magazine, Germany/France

Even today, the year of Iannis Xenakis’ birth is not known with certainty: 1921, according to some identity papers, 1922 officially… The latter date was eventually adopted by the composer and by History. Thus we celebrate this year the 100th birthday of an utterly atypical and unclassifiable man: revolutionary but calm, excessive yet meticulous, both a musician and an architect, passionate about music, numbers and laws as well as liberty, and deeply attached to his homeland, Greece… Ancient Greece.

Origins

Xenakis liked to recall the meaning of his name: “small stranger” or “gentle stranger”. The “-aki” suffi is a diminutive that can signify either “small” or “gentle”. Xéno (Ξένος) itself means “stranger”. This meaning was not without importance for a man who was, or felt like, a stranger wherever he went. Born into a Greek community in Romania, raised at a boarding school in Spetses (a Greek island situated in the Gulf of Nafplion), and later exiled to France, he often said that he had been “born 25 centuries too late”, feeling as though he had been parachuted from Ancient Greece into the 20th century West.

Music was present throughout his childhood, and when his mother (who would die when he was 5 years old), gave him a flute, his interest in music was definitively awakened. During his years at the boarding school in Spetses (Greece), he immersed himself in studies of philosophy, mathematics, and the sciences. In 1938, he went to Athens, taking the entrance exam for the Polytechnical College with the intention of becoming an engineer. In the evening, he taught himself analysis, counterpoint, and harmony…

A new birth

In 1946, Iannis Xenakis, who had already been politically engaged for some time (he would be imprisoned several times and even condemned to death), was hit by shrapnel, which destroyed half his face and cost him the use of one eye. (The British had liberated Athens in 1944, but continued to fight communist demonstrations, in which Xenakis occupied the front lines.) Rescued at the point of death, he survived and secretly fled Greece in 1947, engineering degree in hand, with the United States as his original destination. He stopped upon reaching France.

In several places in his music, he tried to recreate the sound of that projectile as he recalled it in his mind — such an overpowering music, the sound of combat in the streets of the capital.

Nature, Antiquity

Before continuing the chronology, it is important to set the scene of Iannis Xanikis’ cosmos. Ancient Greece was his imaginary Eden, nature his absolute model. His vision of the world was not centered on Man: It was intensely global, monumental – a vision that, like his works, was dazzling, with an intensity bordering on saturation. He wanted his works to “change Mankind”.1

Xenakis and architecture

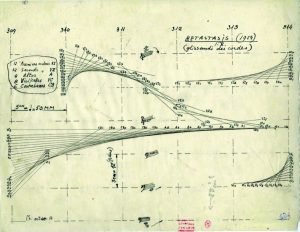

Arriving in Paris in 1947, he joined Le Corbusier’s architecture firm as an assistant. Intensely interested in the physical as much as in philosopy, the arts and sport, he began exploring the links that unite music and architecture. Starting in the early 1950’s, he abandoned traditional musical notation paper in favor of graph paper, much better suited to his profoundly non-linear system, which was based not on harmonic theories but on… mathematical laws. Written in 1954, Metastaseis would be his first work in which the music results entirely from mathematical processes used in architecture.

That work, 10 minutes in length and arranged for 65 instruments, is the poster child for the synergy Xenakis established between music and architecture: Metastaseis is admittedly the application of a mathematical idea, but the graphics sketched on the score would later serve as the basis for the design of the Phillips Pavillon, prepared for the Brussels Universal Exposition of 1958. That Pavillon would be the last collaboration between Xenakis and Le Corbusier, but not his last construction, the Diatope — a space created for the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou in 1978 and intended to host his La Légende d’Er, a musical work that would apply mathematical principles to acoustical prerequisites (for example, the need to obtain the maximum open volume possible because of the trajectory of the laser beams used in the performance).

Xenakis and his musical era

When he arrived in Paris, Xenakis wanted to continue his musical training but was refused by all contemporary composition teachers, who considered his work to be “not music”. All except one — Olivier Messiaen, who advised him to persevere in pursuing his atypical path and gave permission for Xenakis to take his courses. Arriving in France during the heyday of Serialism, he countered the outmoded linear (and in its essence, melodic) musical discourse with a sound movement he called “ of masses ”, that is, one of large complex ensembles, no longer governed by the laws of harmony, but by those of numbers, which in turn were inspired by the laws of nature. He compared these movements to the sounds produced by nature, like the sound of rain that results from the sound of thousands of drops of water: From the midst of that sound, we are unable to perceive it in a linear manner. Changing the sound of a single drop modifies the entire work as well.

Xenakis was so opposed to melodic systems that he wrote La crise de la musique sérielle (The Crisis of Serial Music). In that article, published in 1955 (in French) in the first issue of Gravesaner Blätter, edited by the German musician Herman Scherchen, Xenakis notes the impasse into which Serialism had led itself: That music is intrinsically limited by the number of 12 sounds imposed on the original series and by their organizational structure. Moreover, Xenakis believed that “linear polyphony” would self-destruct because, in his opinion, the complexity of its construction made it impossible for the listener to consider each individual line of sound. That essentially linear system resulted in a result approaching that of a single mass of sound, no longer separate musical lines. He puts forth the independence of each sound – their freedom, in other words. But a fatal question then faced Xanikis, who in fact preferred the movement of masses inspired by nature: “How to make those masses intelligible?”. To do that, he turned to the physical and mathematical laws that guide architecture, most notably to theories of probability. His first so-called “stochastic” work (composed by using the calculus of probabilities in particular) was Achorripsis (1957) for 21 instruments.

Spatialization yesterday and today

We saw earlier that Xenakis thought globally. For him, mankind is a miniscule point, a point situated and immersed in the universe. The sound masses he imagined were always inspired by nature: a group of birds, a galaxy made up of thousands of stars, ocean currents… Running parallel to his research on sound (he would become a pioneer in the field of computer-assisted music), he set his sights on a spatialization of music as well as of light, which he would then integrate into his compositions through flashes, laser beams or incredible projectors. This spatialization, his antidote to linear music, which is so evident in his scores, didn’t stop with musical composition. Xenakis at times dispersed the musicians among the audience – or the opposite (notably in Nomos gamma in 1967). Today that strategy of musical immersion does not seem unexpected, but back in the 1960s, concerts were still all “out in front” : performers on one side, the public on the other! In our days, music – notably vocal music — takes delight in being able to offer an up-close experience by positioning the musicians in the middle of, or around, the public, whether or not the work in question was composed with that in mind.

Vocal music

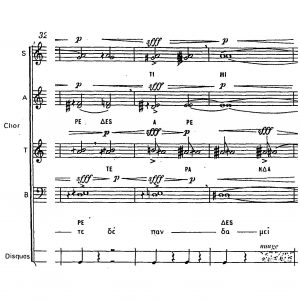

Beginning with Zyia in 1952, Xenakis composed with and for the voice, and his vocal output was mainly choral. His use of the human voice is like his entire production: gladly liberated from the writing habits and numerous rules of composition, most notably vocal rhetoric. He applied mathematical principles to the voice as well as to instruments, and developed a notation specifically tailored to produce the desired effects [ NUITS EXTRACT] such as his own symbols for glissandi, notes advising the imitation of an instrumental sound (“pizz.” for example) or graphic representations calling on the singers’ imagination (such as sound clouds). Nuits (1967), for 12 voices, explores multiple forms of vocal expression — clapping, coughs, sighs, wheezing, etc. Sounds that do have a pitch are paired with a plethora of accidentals – difficult to read, but a fascinating work.

Xenakis utilized an archaic language resembling Ancient Greek more than its modern counterpart in vocal compositions like Orestie, a work for choir and 14 instruments regularly performed by professional vocal groups.

by Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Reproduced by permission of Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.

Solely for the use by International Federation for Choral Music

The Polytopes

The Polytopes, whose premier was given in 1971 at the Festival of Shiraz, in Iran, (Polytope de Persépolis) are a Xenakian concept that synthesizes Xenakis’ different research domains. Of these, the most impressive and most symbolic was probably the Polytope of Mycenae, performed in Greece in 1978, which combined the music of Orestes (on texts by Aeschylus), the songs for choir and instruments To Helen and Oedipus at Colonne, several songs and interpolations in the ancient Mycenien language, tales from The Illiad, Psappha for solo percussion, Persephassa for percussion ensemble, and Mycenae Alpha, an electro-acoustic work (entirely composed with the help of the UPIC, a tool developped by Xenakis, consisting of a kind of graphic tablet connected to a computer program that transformed drawings into sound). By placing ensembles in different locations throughout the valley of ancient Mycenes, the immersion is already musical. But Xenakis naturally added other sensory éléments to it: children carrying torches whose luminous flames formed patterns, light effects produced by projectors borrowed from anti-aircraft defenses, and even a troop of 3,000 goats whose two horns were adorned with candles! The inhabitants of the region were involved in this immense production, side by side with the University of Provence choirs, the Lorraine Philharmonic Orchestra, the Strasbourg Percussion Ensemble… all under the direction of the Swiss maestro Michel Tabachnik.

This immersive and oversized (for the era) event attracted 40,000 spectators five nights in a row. But above all else, this knowledgeable mix of antiquity, modernism, research, lights, acoustic music for choirs and percussion, and an electro-acoustical composition (Alpha), was the first presentation of a work by Iannis Xenakis on Greek soil – in 1974, when for the first time after 27 years of exile, Xenakis once again set foot in his native Greece.

And Today?

Contemporary composers of electro-acoustic music (and many others, such as his student Pascal Dusapin) walk in the footsteps of Xenakis. His Equipe de Mathématique et Automatique Musicales, created in 1966, renamed several times and finally calling itself the Centre Iannis Xenakis, was for decades the laboratory of muscial and scientific creations (notably with the creation of the UPIC tool cited above).

As for the Polytopes (Persépolis, Cluny, Montréal, Mycènes…), they remain a distinctive, trail-blazing element in the work of Xenakis. Shortly thereafter, the French musician Jean-Michel Jarre, at the time a young composer of electro-acoustical music and a student of Pierre Schaeffer (also a colleague of Iannis Xenakis in Paris), took inspiration from them for his first major open-air concert in Paris. The concept was later reproduced in different musical styles in various regions of the world, with multi-disciplinary outdoor spectacles combining electro-acoustic sound, multiple music groups, light-shows and dramatizations. As for the Valley of Mycenes, after 1978 it never again served as the theatre for Polytopes, but if Greek theaters again echo the songs and tales of Homer and Sophocles, the ancient Mycenian site still remembers the sensational – and triumphant – sounds of the elusive and unique work of the forever unclassifiable mathematician-architect-composer Iannis Xenakis.

1 From an interview available in the documentary film “Xenakis Revolution: Architect of Sound”, www.arte.tv

CDs

- Xenakis, Choral Music (Medea; Nuits; A Colone; Serment; Knephas). New London Chamber Choir, Dir. James Wood, Hyperion, 1998.

- Xenakis: Phlegra – Jalons – Keren – Nomos Gama – Thalleïn – Naama – A l’île de Gorée. Ensemble Intercontemporain, Michel Tabachnik, Pierre Boulez, Sylvio Gualda, Ensemble Xenakis et al. Warner Classics, 2007.

- Collection of 14 CDs, works of Xenakis, Mode records.

Books

- Xenakis Matters. Contexts, Processes, Applications. Sharon Kanach, Ed. Pendragon Press, 2012

- Kanach, Sharon: Performing Xenakis. Pendragon Press, 2010

- Music and Architecture. Architectural Projects, Texts, and Realizations of Iannis Xenakis. Sharon Kanach, Ed. Pendragon Press, 2008 (available in French from Editions Parenthèses under the title “Musique de l’architecture”)

- Iannis Xenakis, un père bouleversant. Mâkhi Xenakis. Actes Sud 2022

Vidéos

- 1966 ORTF broadcast with Iannis Xenakis on the subject of Metastaseis, document INA : https://bit.ly/ORTF-X

- 1967 ORTF interview with Iannis Xenakis, document INA : https://bit.ly/inter-X

- Reporting on the Polytope de Persépolis on the Spatial Music Forum of YouTube: https://bit.ly/PerseYT

- Reporting on the Philips Pavillon on the Spatial Music Forum of YouTube: https://bit.ly/Pav-Phi

- Video-report on the Polytope de Mycènes by Greek Radio-Television ERT : https://bit.ly/Mycenes

ISABELLE MÉTROPE is a singer, a conductor and the managing editor of the International Choral Magazine. She studied applied languages and music management, as well as conducting, singing and pedagogy, which is the cause as well as the result of a compulsive curiousity naturally leading to a strong interest in systematic musicology. Apart from singing solo and in several professional choirs, her favorite activities includes page setting, translating, baking cakes, taking pictures and travelling around the Mediterranean. Email: choralmagazine@ifcm.net

ISABELLE MÉTROPE is a singer, a conductor and the managing editor of the International Choral Magazine. She studied applied languages and music management, as well as conducting, singing and pedagogy, which is the cause as well as the result of a compulsive curiousity naturally leading to a strong interest in systematic musicology. Apart from singing solo and in several professional choirs, her favorite activities includes page setting, translating, baking cakes, taking pictures and travelling around the Mediterranean. Email: choralmagazine@ifcm.net

Translated by Anita Shaperd, USA