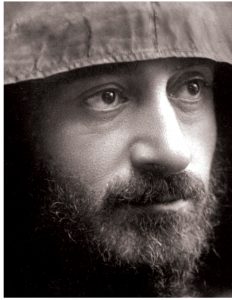

Komitas, the quintessence of Armenian Music

By Arthur Shahnazaryan, conductor, composer and musicologist

INTRODUCTORY NOTES

Komitas is the founder of the Armenian compositional and musicology school. He single-handedly achieved in Armenian music what numerous musicologists, composers and ethnologists achieved in the field of European music. Komitas returned the identity, spirit, and genuine character of his people to them, traits that were buried in the millennial depths of Armenian history.

Komitas transcribed more than 1,500 folk melodies originating from the various regions of historical Armenia. These are gems of the Armenian musical Heritage, which he saved from permanent loss. His transcriptions were carried out with extraordinary mastery, and he even recorded alternative variations of many of the pieces.

The songs depict practically all aspects of the Armenian people’s lives. The melodies he collected were divided into categories such as ritualistic songs, festive songs, work songs (ploughing, bread-making, planting, harvesting, carting, threshing, wheat grinding, various home chores, woodworking, goat-milking, cradling, et cetera), epical songs, lyrical songs, songs addressing nature, refugee songs, laments, children’s songs, banters, dance songs, battle songs, pagan songs, dance-melodies of ancient, sacerdotal practice, and many others.

From the material he transcribed, Komitas authored exceptional musicological studies. He examined the natural environment in which a song was created and the lifestyle of the people singing it; he carried out unparalleled analyses, “dissecting” a song to demonstrate its structure, the skeleton which framed its muscles, blood, and most delicate sinews; he categorised its emotional character and the type and design of its expressive gesture; he unravelled the specifications of its idiomatic dialect and intonation; he clarified the types and rules of its musical metrology; he drew out generalisations and revealed the special rules particular to Armenian music; he codified the musical grammar of Armenian musical expression. His probings were indeed exceptional and unprecedented. In the musicology world, one can hardly find comparable research of such meticulous analysis as that found in his “The Ploughing Song of Lori.” With his unique musicological methodology, he studied the structure and rules of folk and sacred music.

Furthermore, he created tables to render all these parameters visible and clear. Here is just one example of a table:

I. AMANAK (CHRONOS, DURATION)

a. Temporal values commonly used

b. Temporal values of punctuation in the melody

buth = blunt (corresponding to the colon)

storaket = comma

mijaket = midpoint (corresponding to the semicolon)

verjaket = end point (corresponding to the period)

c. Temporal values of accentuation

shesht = accent

harts = question mark

yerkar = long

d. Ornamentation

antsik = passing tone

kankhik = anticipation

hapaghik = suspension

shaghkap = tie (conjunction)

shegh = alternation

e. Rhythm

taghachaputiun = prosody (metrics: 3/4, 2/4 et cetera)

chap = tempo (broad-paced, et cetera)

II. MELODY

- sahman = span

- qarunak = tetrachord

- kazm = structure

opening patterns

tonic (of the melody)

phrases: recitation phrases, cadential phrases, ending phrases

punctuation

accentuation

embellishments

disjunct leaps

basic patterns of the melody

variations of the basic patterns

foundations of the melody

III. VOGI, HAGAG (PNEUMA, SPIRIT)

a. The types of emotion

b. The role they have in emotive expression

- duration, with its constituent parts

- melody, with its entire structure

Komitas, with prodigious awareness, acquainted himself not only with Armenian music, but with Eastern music in general. He also immersed himself deeply in European music when he continued his education in Berlin. There, eminent musicologists and professors thought of Komitas, a student, as a colleague. He became a member of the newly created International Music Society of Berlin, which was headed by the prominent musicologist, Oscar Fleischer. This organisation eventually garnered wide acclaim throughout Europe. It hosted international symposia, published scholarly works, and organised concerts and lectures, in which Komitas also participated. Oscar Fleisher and Max Zeifert (secretary of the IMSB), in reference to the lecture-presentations of Komitas, wrote:

“I consider it my duty to express my gratitude to you in the name of the International Music Society in Berlin. I thank you for the vigour with which you, with your lectures about Armenian music, promoted the aims of our Society. Your learned and profound lectures helped us deeply examine that music, which until now was almost unknown, and which is capable of teaching us Europeans many things. The work you have embarked on is not easy at all, and I can emphatically express on behalf of all those who have heard your lectures (including people who have earned exceptional acclaim and international recognition in the scholarly world) that your laborious work and efforts are not in vain. You would be contributing appreciable service to current scholarship if you published your works, and I would be very glad to be of help to you in this regard.

With utmost respect,

Yours truly, Oscar Fleischer.”

“The profound glance with which you introduced us intimately to the power of a sophisticated and noble culture which had remained unknown to us, your surprisingly erudite presentation of that tradition, which veritably has a compelling significance in a purposive understanding of our early Western civilization, your perfect skill in lecturing and singing, these are all things which have not only amazed us, but which shall also remain vivid in the memory of your listeners. With this presentation you have earned not only the appreciation of our Chapter, but also, most certainly, the definitive praise of the great cultural role your nation has had.

Adding my expressions of great respect to the above, I have the honour, venerable Priest, to sign this letter.

Yours truly, Dr. Max Zeifert,

Secretary of the International Music Society, Berlin.”

Komitas further restored the Armenian ecclesiastical music of the 5th to the 15th centuries as much as he could. This was a music tradition that had its roots in the pre-Christian era, as the Armenian Church incorporated the melodies of ancient traditions into its liturgy. Beginning with the 9th century, ecclesiastic melodies were transcribed into the Armenian musical notation system called “khaz.” However, by the end of the 16th century, these symbols eventually became completely forgotten, such that no one could read them anymore. For nearly 300 years after, songs were passed on orally, and were therefore subjected to perversions and foreign influences (specifically those similar to Eastern music styles). Komitas first cleansed these songs of inappropriate, superfluous flutterings and embellishments, restoring them to their previous simple yet splendorous style. For twenty years he busied himself with deciphering the lost art of the medieval “khaz” (neumes), and found the key to read its simplest symbols and figures. However, the impending First World War and the 1915 Genocide of the Armenians brought the creative life of Komitas to an end.

Komitas was responsible for founding the Armenian compositional school. During his years of study in Berlin, Komitas’s teacher, Richard Schmidt, had affirmed that Komitas created an altogether novel style of national compositional art. Schmidt said:

“You have created a noble and unique style, which, like a red line, rides out brightly through the entirety of your writings and compositions. I have labelled that style as the Armenian style, because it is a novelty in the world of our musical experience.” He is also quoted saying: ” Komitas was a fanatic Easterner, ready to shed blood for each and every note.”

Komitas is also behind the creation of a new national school of composition, with harmonic and polyphonic arrangements of Armenian songs. His renderings sprang from the particular configurations of Armenian Monody. Monody remained in the heart of his polyphonic renditions because the parameters of Armenian Monody are different from the European ones. For instance: Armenian modes are underpinned not by the European octaval structure, but by a system of chained unification of tetrachords, where the fourth member of the first tetrachord is, at the same time, the first member of the next tetrachord. From that enchainment of tetrachords comes forth a minor heptachord, whose tonic would thus be in the middle. There are six types of tetrachords, from whose various enchained combinations emerge different modes and melody-types. Another factor of national character is texture. Komitas gleaned, for instance, the texture of his piano works by studying the particular performance potential of our folk instruments.

Komitas says:

“We Armenians must create our own compositional style and then go forward confidently. …I will reach my objective, even if I have to devote my entire life to it.” He writes: ” People expect a deep and broad familiarity with the essence and requirements of European classical music from we Armenian musicians. Stressing the importance of this fact, I must nevertheless add, that if we Armenian musicians master the fundamentals of Western classical music, its developmental rules and precepts, but not be aware that our national music also has its specifications and rules and requirements deriving from it, then we betray ourselvesTo randomly replace our music models with the European ones would be the greatest offense, which has often occurred in this starting point of our musical renaissance, and I suspect that this will still go on.”

Studying the works of Komitas, Thomas Hartmann wrote: “The works of Komitas are not compositions in the usual sense, but creations of style.”

On the basis of popular singing and the uniqueness of Armenian vocal timbres, Komitas also created a national school of singing. Being an exceptional singer, he became its foremost representative (samples of his singing have been preserved on old recordings).

Beside his creative work, Komitas also carried out a variety of educational efforts. He had numerous pupils, and even assisted in preschool programs; he taught in educational institutions and developed music curricula for future students. He also created and directed choirs, which gave numerous concerts (notable under his leadership, were the choir of the Mother Cathedral of Holy Ejmiatzin and his unprecedented 300-member choir in Constantinople). Komitas has given lecture-recitals in cities in Armenia, in Georgia, and across Anatolia, Egypt, Jerusalem, Berlin, Paris, Zurich, Geneva, Lausanne, and Venice.

Komitas delivered his final lectures in 1914, in Paris, at the symposium of the International Music Society (by that time the organisation, which was established in Berlin, had greatly expanded, and included 400 representatives of international musicology). Thereafter in 1915, Komitas, along with hundreds of Armenian intellectuals, were ostracised by the Young Turk government into the depths of Anatolia, and he became an eyewitness of the Turkish atrocities toward his people. One and a half million Armenians were massacred during that time. Saved miraculously from slaughter, Komitas passed twenty fruitless years in mental asylums before passing away in 1935.

Arthur Shahnazaryan was born on July 16 in 1958 in the village of Vahagni, Lori Region, Armenia. In 1986 he graduated from the composing, conducting and music departments at the Komitas State Conservatory of Yerevan. From 1988 to 1994 he was the head of the Yerevan State Conservatory of Folk-Art Cabinet. From 1995 to 1997 he has been the head of the Programming and Methodological Department of the Ministry of Education of RA. In 2016 he assumed the position of artistic director of the “Akunk” ethnographic ensemble of the Ministry of Culture of RA. Mr. Shahnazaryan is a member of the Board of Composers Union of Armenia and has published various scientific works about Armenian medieval khaz notation, culture, ethnography, folk art and education. He is an author of musical compositions and a Komitas expert. He principally rejected any kind of awards or prizes. He has been president of juries in many festivals and competitions, organized many concerts and musical performances in all Yerevan state concert halls. He has held concert-lectures and educational programs in Romania, Hungary, USA, France, Germany, Denmark and Norway. Email: alschoir@gmail.com

Arthur Shahnazaryan was born on July 16 in 1958 in the village of Vahagni, Lori Region, Armenia. In 1986 he graduated from the composing, conducting and music departments at the Komitas State Conservatory of Yerevan. From 1988 to 1994 he was the head of the Yerevan State Conservatory of Folk-Art Cabinet. From 1995 to 1997 he has been the head of the Programming and Methodological Department of the Ministry of Education of RA. In 2016 he assumed the position of artistic director of the “Akunk” ethnographic ensemble of the Ministry of Culture of RA. Mr. Shahnazaryan is a member of the Board of Composers Union of Armenia and has published various scientific works about Armenian medieval khaz notation, culture, ethnography, folk art and education. He is an author of musical compositions and a Komitas expert. He principally rejected any kind of awards or prizes. He has been president of juries in many festivals and competitions, organized many concerts and musical performances in all Yerevan state concert halls. He has held concert-lectures and educational programs in Romania, Hungary, USA, France, Germany, Denmark and Norway. Email: alschoir@gmail.com

Translated from Armenian by Vatsce Barsoumian (Conductor, music director of Lark Musical Society of Glendale California, USA)

Edited by William Young, UK