Latin American Music

By Oscar Escalada, Composer, Arranger, Choir Conductor and Musicologist

When you hear talk about Latin American music, immediately you think of lively, rhythmic, joyful and syncopated music. However, it was not always like that. The music of the Americas is the result of a blend of three great cultures: Native, European and African. A unique flavor is given to this music, and a wide range of diverse rhythms and styles are heard in jazz, tango, salsa or bossa nova, although they are all quite different from each other.

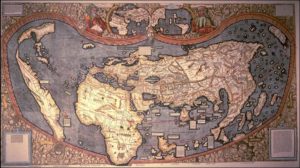

Researchers call this blend an “Indiana culture’, due to the incorrect idea that the first Spanish conquerors had found their way to the Indies through the West. After Amerigo Vespucci discovered that it was not the West Indies, as Christopher Columbus had originally thought, but instead a whole “new world”, in 1507 the German geographer Martin Waldseemüller published a map in Cosmografia Introductio with the scheme sketched out by Vespucci. He called this new land the Land of Americo. However, since all the other continents bore female names, the Land of Americo soon became “America”. Thus it is absolutely incorrect to call the United States of America, America and its citizens Americans. That idea completely ignores all the other American countries from Canada to South America and all the people in those countries. All the other American countries would be delighted if the United States citizens realized this error and gave their country any name of their choice, but not “America”. (See figure)

However, this does not change the origin and development of the Indiana culture that has influenced the music of the Western Hemisphere in many ways.

Briefly, the musical elements that each culture brought to the new world and their strong influences may be described in this way: Europe brought modes and scales, Africa contributed syncopated rhythms and Natives added tritonic [scales of just three notes, spaced like a major chord in the European tradition, but probably based on the overtones of the native wind instruments, and without the harmonic function of a major chord – translator, after consulting the author] and pentatonic scales. Africa brought all kinds of drums, and Europe contributed strings and winds. Natives had just a few string instruments which were mainly monochords and not used for melodic purposes but rather as rhythmic ones, like the Brazilian berimbau, and many different kinds of aerophones (see figure) and percussion instruments, such as idiophones, were used. The cordophones gradually adapted to the various regions, and thus, on the basis of the vihuela (guitar), instruments developed like the charango (see figure), used in Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, or the cuatro in Venezuela.

Indiana culture recognizes two areas of influence: the area of tunes in triple time on the western part of the continent, and the area of music with two beats to the bar on the eastern side of the Americas, as far as they were conquered by the Spaniards. The Spaniards, residing in the two most important cultural centers of Mexico and High Peru, influenced the western area, and the eastern area received its influence directly from Africa.

The influence of music in triple time extended to the rural areas from Mexico to Argentina. The similarities in their rhythmic patterns such as superposition and/or juxtaposition of 3/4 and 6/8 are characteristic of much Latin American music.

The music in duple time, dominant in the east, was, however, more urban, and it is better known in the rest of the world. The influence of black music has been so strong throughout the continent that we can easily say that there is not a single note in the music of the Americas that has not been influenced by black origins.

Hanaqpachap

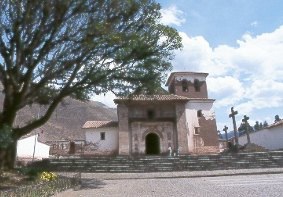

The first polyphonic composition in the New World that has come down to us is the Hanaqpachap. It was published in Cusco, High Peru, in 1631, and preserved by a priest in the town of San Pedro de Andahuailillas (see figure), Don Juan de Bocanegra.

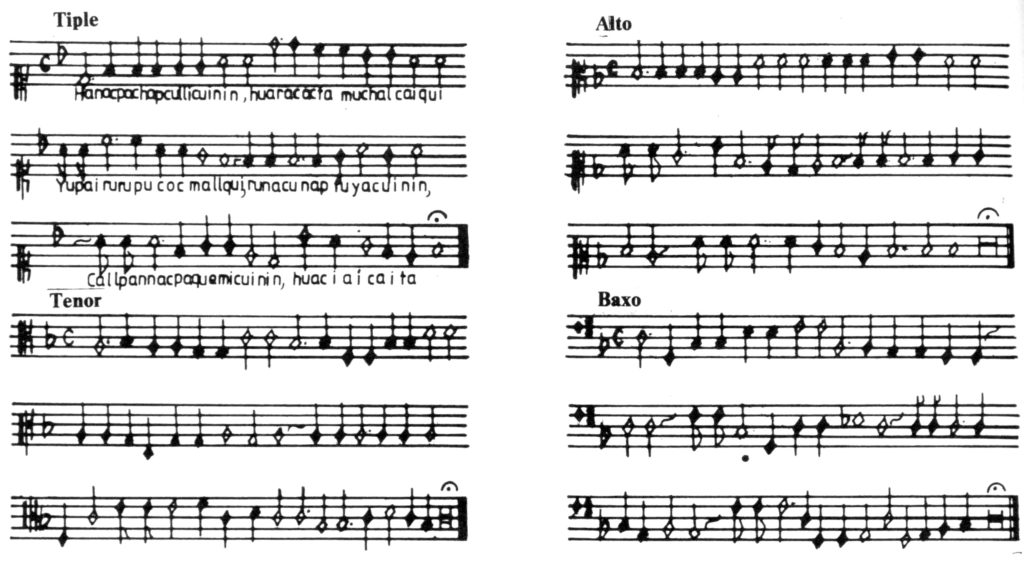

Hanaqpachap is a good example of this cultural blend, as it is written in the Renaissance style but in the language of the Incas, Quechua. (See figure).

(Click on the image to download the full score)

Though the composer is unknown, in my opinion it may have been written by a native student of music, as the piece contains some unorthodox parallels between the parts as well as unprepared dissonances, something which was unusual at the time. (1)

Music in Argentina

Folk music

Similar to music in many countries in Latin America, Argentinian music is also split into pieces using duple or triple time. According to the maps shown previously, the western part of the country received the Spanish influence from High Peru in the times of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata. The “Way of Silver” crossed the Viceroyalty from northwest to southeast, ending in the port of Buenos Aires, in order to cross the Atlantic Ocean on its way to Spain.

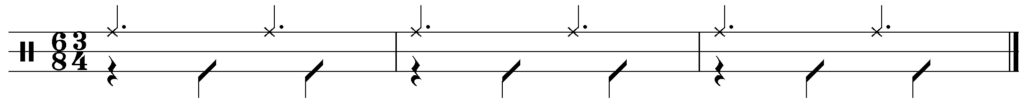

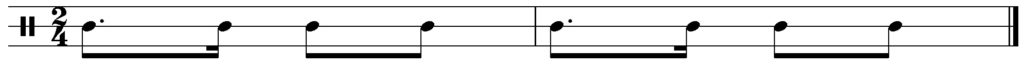

The basic rhythm in this area uses the juxtaposition and superposition of 3/4 and 6/8 as shown in the figure below.

Folk rhythms like chacarera, gato, zamba, cueca, etc. employ this pattern. They can be played faster or slower depending on each style. Zamba is slower than chacarera, gato or cueca. The difference between these songs is based on its form. This needs to be maintained in the case of dances for separate couples that each have specific choreography. One can say that gato and chacarera have the same rhythm. The difference lies in the form, because of the choreography.

Independent of this use of triple time, we also find duple time, like in the carnavalito.

Tango

A great and important immigration from particularly Spain and Italy, but also Poland, Germany, Hungary and other nations took place at the end of the 19th century and between WW1 and WW2 in Uruguay and Argentina which had a dramatic influence on tango, candombe and milonga, the three urban rhythms of the region with binary patterns. But the contribution of black music was also of great importance, particularly in the candombe. However, the basic pattern of these rhythms also occurs in other musical styles that we find throughout the Atlantic coast of America, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Rio de la Plata. This pattern has different names, depending on the country in which it was developed: Habanera in Cuba, Maxixe in Brazil, Tango in Argentina, Candombe in Uruguay, etc. We even encounter it in the USA in early blues and ragtime such as the St. Louis Blues by W. C. Handy or Solace by Scott Joplin.

In each of these regions, the pattern underwent its own special development. As an example, let´s investigate the tango.

In my opinion the word tango has its origin in the Quechuan tanpu which means “a place where people meet”. The Spaniards changed this word to tambo due to the lack of the phonetical group ‘np’ in Spanish. Later on it became tango. (2)

Around 1870 the rhythm of tango hardly differed from habanera, candombe and milonga, really only in the one feature that the Candombe has an accent on the last eighth note of the bar, and the milonga one on each heavy beat.

The candombe consolidated itself in Montevideo (Uruguay) and had a different development from the milonga which remained popular in the Province of Buenos Aires, even though it was still alive in the urban area of Buenos Aires, where, however, it more or less merged with the tango.

Around 1940, under the influence of war and military governments, the tango started to be played as a kind of march (*) and its rhythm was:

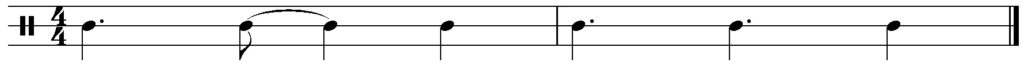

Then, around 1960, under the influence of Astor Piazzolla, the rhythm gradually became:

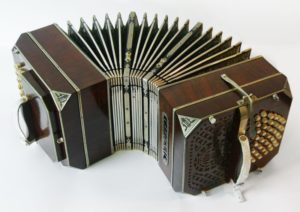

(*) The violinist and bandoneon (see figure) player Emilio Balcarce (1918-2011), founder of the Buenos Aires Tango School Orchestra, mentioned this in his classes. Maestro Balcarce died at the age of 92 and witnessed the history of this genre.

The relationship between classical and popular music

Classical composers such as Alberto Ginastera, in his ballet Estancia, or Carlos Guastavino in his Indianas for SATB and piano (3), or Ariel Ramirez in his Misa Criolla (4), as well as many others used folk rhythms as a source of inspiration for their works. Some of these composers made subtle use of them, whilst others took them over unchanged.

On the other hand, tango composers also took over ideas from classical music. For example, Astor Piazzolla used compositional devices like fugues, whereas in “The four seasons of Buenos Aires” he fell back on Vivaldi´s “Four Seasons” (5). Verano Porteño, Otoño Porteño, Invierno Porteño and Primavera Porteña (6) comprise this suite. This suite consists of the movements Summer, Autumn, Winter and Spring in Buenos Aires. In Invierno [Winter] , Piazzolla offers a kind of homage to Vivaldi by using a characteristic harmonic sequence at the end.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that great poets such as Jorge Luis Borges cooperated in the production of lyrics for tangos, thus showing the great importance that Argentineans accord to their national music.

Some publishers and links focused on Argentineans and Latin American Music:

Latin American Choral Music – www.latinamericanchoralmusic.org

Latin American Choral Music Series –

http://www.kjos.com/sub_section.php?division=2&series=109

Ediciones GCC – www.gcc.org.ar

Porfiri & Horvath Publishers (Los cantares de América Latina) –

Earthsongs – www.earthsongschoralmusic.com

Notes

1) – Oscar Escalada. Hanaqpachap, the first published work (and composed?) in the New World, Research undertaken for the University of La Plata, published in the Choral Journal, downloadable from www.oescalada.com.ar

2) – Oscar Escalada. Origen de la voz tango. ibid.,

3) – Oscar Escalada. Carlos Guastavino, ibid. Published in the International Choral Bulletin, downloadable from www.oescalada.com.ar

4) – Oscar Escalada. Misa Criolla, ibid., published in the Choral Journal

5) – Oscar Escalada. Astor Piazzolla, ibid.

6) – The whole suite is published for SATB and piano by Neil A. Kjos, music publisher in San Diego, California.

Edited by Diana Leland, USA and Irene Auerbach, England