Pathways and Traditions concerning Handel’s Messiah 1742 – 1876 – 2015

Comments on the programme of the “International Choir Academy 2015” in Spoleto

by Torsten Roeder, musicologist and choir conductor

Prologue

In the summer of 2015 one hundred choristers, solo singers and instrumentalists from all over Europe met in the Umbrian town of Spoleto in the heart of Italy to take part in the International Choir Academy under the directorship of Prof Dr Bodo Bischoff. This institution, in existence for the last 25 years, was intended, in this its jubilee year, not only to take place in an unusual place but also to offer a special musical programme that would represent the international framework of the project in a particularly apt way: the rehearsal plan for the week was dedicated to George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, one of the most famous oratorios in music history. The project ended with a fully fledged evening concert in the Teatro Nuovo in Spoleto (illustration 1); as an encore, the Hallelujah chorus was sung together with numerous Italian choir singers.

It is possible to establish many links between the project of the International Choir Academy and the eventful history of performances of the Messiah, during which customs and practices evolved, some of which are alive and well to this day. These links supplied the inspiration to this essay.

The long path to Rome

Handel (Illustration 2) had composed the great oratorio in 1741 and had it performed in the years that followed first in Ireland and then in London. Within a few decades it had then also spread abroad, reaching Florence in 1768, 1770 New York and Hamburg in 1772. Within only a few decades the Messiah had conquered many – and, in the 19th century, nearly all – the important musical cities of the Christian world – not, however, the world centre of church music: in Rome the oratorio was only first heard in 1876, after it had already been performed for a long time in every nook and cranny of the world, and more than 130 years after its creation. Why so late? We would have expected the work really to have been accepted immediately into the musical repertoire of the Roman churches because of its thoroughly spiritual subject – after all it retells the life story of the Saviour.

One of the reasons was the Protestant background of the work. Handel’s Messiah had come into existence within the Protestant sphere, with its text based on the King James Bible, a product of Anglican church’s split from Roman Catholicism. To this day the Messiah – this is its original title – stands for the tradition of the English-language oratorio as no other piece of music does. It is remarkable that it is with this work that Handel had introduced the – originally Roman-Catholic – tradition of the oratorio into the Anglican world in the first place.

From blasphemy to massed choirs

A further reason is to be found in the genre of the work. ìBeing an oratorio, at the time it was hardly ever performed in churches, as is the custom now, but primarily in concert halls, supplying edifying entertainment and cash for charity. Thus it possessed religious qualities, but no liturgical ones. In the 18th century – even in England – it remained the target of criticism for a long time, as the use of words from the gospels for an evening’s entertainment was considered blasphemous.

It was only with the start of the establishment of a civic musical culture in the 19th century that this was to change. Choral singing increasingly established itself as a new expression of cultural and religious identity. Now, in the English-speaking world, the Messiah was performed using choral and orchestral forces whose size increased steadily. Spectacular concerts with hundreds, sometimes even with several thousands, of singers were no rarities (Illustration 3).

In 1876, the year of the first performance in Rome, the Centennial Exhibition opened in Philadelphia, then one of the largest cities in the USA, with an extensive celebration. Alongside numerous speeches and various musical offerings, the Hallelujah from the Messiah, together with a doxology, provided the festive culmination of the event, performed by 1000 singers and 150 orchestral musicians: a celebration that was at the same time religious and festive.

In papal Rome, however, Handel was known primarily as a composer of operas, his name virtually non-existent in concert programmes. Handel himself had been forced to witness the Roman opera having to close at the very time he was staying in Rome, because of a ban.

Early music newly taken care of

Nor was it under the roof of a church that the Messiah did eventually get staged in Rome for the first time, but within the framework of a select musical society, the so-called Società musicale romana. This society was an academic musical association particularly keen on supporting “early music”. In this year, they inaugurated their new building, now in the Palazzo Doria-Pamphilj (Illustration 4) in the south-western corner of the Piazza Navona (in our day the Brazilian Embassy) with a performance of the Messiah.

The director of the Società musicale romana, who had selected the Messiah and now performed it in the association’s new premises, was called Domenico Mustafà (Illustration 5). He was born in 1829 in Sellano, close to Spoleto in the province of Perugia. He was one of the last castrati singers to live into the 20th century. The real peak of castrato singing was in Handel’s time, the 18th century; in the course of the 19th century the practice dwindled more and more (and finally, at the start of the 20th century, the Vatican forbade it).

Ambition and talent soon took Mustafà to the Sistine Chapel in Rome (“Cappella Sistina” describes not only a sacred building, but also its resident choir). In 1860 he was appointed Maestro Direttore della Cappella Musicale Pontificia Sistina, the director of the papal musical establishment – one of the top jobs available at the time for church musicians. Above him was only the Direttore Perpetuo (“eternal choir conductor”), a post to which he was then appointed two years later.

For two months Mustafà rehearsed his Roman choir which consisted of about a hundred female and male singers (and thus bears some resemblance to the International Choir Academy). In this respect alone the performance differed from the mass productions customary within the realm of the Anglican tradition. The 25 sopranos, 24 female altos, 25 tenors and 33 basses (the names of all of whom were listed in the programme) also came from well-off, educated backgrounds [whereas particularly in the north of England, many of the singers would have been poor – translator].

Another unusual feature was the fact that – something that in our days is fairly rare – all 51 items were performed. The scale of concerts of the time can indeed be compared to that of epic cinema films. Today, complete renderings are quite rare. For the International Choir Academy, too, a selection was made – a legitimate way of proceeding as Handel, too, was in the habit of adapting his performances, time and again, to the local conditions.

tutto buona, tutta bella, e tutta difficile …

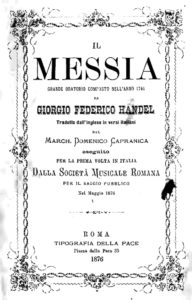

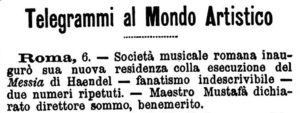

The performance of the Messiah on 5 May 1876 (Illustration 6), which was to be followed by two more, achieved – according to the enthusiastic reports – an excellent standard. The periodical Boccherini wrote that the concert had not only been very good, but extraordinarily so (“non fu soltanto ottima, ma eccezionale”); the critic of Il Mondo Artistico reported a “fanatismo indescrivibile” (Illustration 7), an indescribable fanaticism, and remarked, concerning the piece: “tutto buona, tutta bella, e tutta difficile” – roughly: cool composition, really beautiful, and damn tricky. He also emphasised the fact that for one thing, you needed people who really knew what they were doing, not dabbling amateurs (“professori e non dilettanti”), and also a conductor who really understood the music (“che capisca bene la musica”).

The critic even referred to the performance in Philadelphia, where the Hallelujah had recently been put on with 1000 singers on the occasion of the world exhibition. Though the number of the American singers was fifteen or twenty times higher than here – so he wrote – it would be physically impossible to achieve a better result. The Gazzetta musicale di Milano attributed the success primarily to Maestro Domenico Mustafà, not only a great artist but capable of transferring to his singers his own way of feeling, of motivating them to the necessary rehearsals, and above all managing to instil into them a holy enthusiasm for the music (“accenderli di sacro entusiasmo”).

1742 – 1876 – 2015

The first performance of the Messiah in 1742, the local première in Rome of 1876 and ours of 2015 by the International Choir Academy (Illustration 8) are separated from each other by more than 130 years respectively. In the intervening periods, the classical music business and Handel reception have undergone several renewals. Handel’s time and also that of the castrati is long over; but although towards the end of the 19th century a consciousness of historical performance practice started to emerge, becoming increasingly acute and often objecting successfully against monumentalism, the custom of massed concerts with huge Hallelujah-choruses has survived to our day. Handel’s composition, however, permits very different manners of reception: as even when Handel himself was in charge, the work absorbs ever-new contextualisations and today, in numerous arrangements, moves effortlessly from performance practice strongly influenced by academic insight to Hallelujah flash mobs in shopping centres.

The project of the International Choir Academy proves that this needs to be seen neither as a dilemma nor as a contradiction, by – in the performances in Rome and Spoleto – falling back on features from both traditions. The week of rehearsals comprising the International Choir Academy (Illustration 9) drew on the learned and music-educational singing tradition of a Domenico Mustafà. However, it was only in the union with the Italian singers for the culminating Hallelujah-chorus that the project reaches its symbolic finality. Not could it have been any different even back in 1876: at the Roman first performance, too, it was not only that “All we like sheep have gone astray” that was encored, but also the famous No 41: “Hallelujah”.

Epilogue

The International Choir Academy 2015 was run in close co-operation with the Italian cultural organisation BISSE in Spoleto. This would have been impossible without financial support by the Goethe-Institute [an official German institution with branches all over the world, working to spread knowledge and understanding of German culture and the German language – translator] as well as the Foreign Office of the Federal Republic of Germany. Two orchestras were available: the Junges Philharmonisches Orchester Niedersachsen and the chamber ensemble of the Accademia Santa Cecilia di Roma.

Performances of the Messiah took place on 4 September in the Sala Accademia in Rome (Illustration 10) and on 5 September in the Teatro Nuovo in Spoleto; there, the Coro dell’Associazione Culturale BISSE under the directorship of Mauro Presazzi also performed Vivaldi’s Magnificat. Repeat performances were put on in Berlin on 6 November in the Kapernaum Church (Wedding) and on 7 November in the Auenkirche (Wilmersdorf).

Translated by Irene Auerbach, UK