Singing a New Song

Liturgical Music in the Australian Landscape

Graeme Morton

choral conductor and teacher

Australia is a society of immigrants, a nation still learning how to acknowledge those of the ancient culture whose home was displaced by European settlement. It is a land of contradictions, whose people are still trying to balance well-loved traditions imported from old countries with new traditions that better reflect the vibrancy and independence of a young nation.

The contradictions in Australian society were there from the start and a brief look at religious considerations in the early British settlement demonstrates one such contradiction. The first fleet arrived in Australia on January 26th, 1789 and just eight days later Governor Phillip swore on the Bible before the Judge Advocate: “I, Arthur Phillip, do declare that I do believe that there is not any transubstantiation in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper.”[1] Thus a religious declaration as to the Protestant nature of this colony was formally declared in the context of the law. The contradiction remains that this cannot have been of any relevance to the 759 convicted thieves and villains who made up the populace at that time.

What was relevant for the convicts was that the religious underpinning of the new colony extended to public morality. Governor Phillip was to cause the laws against blasphemy, profaneness, adultery, fornication, polygamy, incest, profanation of the Lord’s Day, swearing and drunkenness to be executed rigorously. This is an interesting list, where the ‘sacred sins’ of blasphemy and profanation of the Lord’s Day stand beside the ‘social sins’ of incest and polygamy, as actions to be condemned by the law.

But the contradictions are not only between the religious authority of the administration and its irrelevance to the population. This was a community established by the forces of rational, inquiring, scientific and secular Enlightenment minds.[2] In this society of the Enlightenment, populated by the un-churched, in an environment foreign to the settlers, we find a surprise and another contradiction – that a tradition of church music is established, albeit a tradition transplanted (largely) from the British Isles.

And so we come to the enigma of Australian liturgical music. That modern Australia, with its highly secular and non-church attending society[3] now produces more and better liturgical music than at any time in Australia’s two hundred year history, and in this land of paradoxes, this music remains hidden from the vast majority of church attendees and unperformed in all but a few churches.

Broadly speaking there are two phases of liturgical composition in Australia. The first centers on the significant number of English musicians who accepted positions in Australia, many of whom composed church music. This phase is extended to include those native Australian composers whose musical style derives from that English tradition. Of the first of these sub-categories, Jeffrey Richards goes so far as to argue that it was music that reflected the high noon of British imperialism between 1876 and 1953, such was the significance of the export of musicians from Britain across the globe.[4] Most of these people did not see themselves primarily as composers. They were mainly organists, community choral conductors and academics. The list of such musicians is too long to list individually but certainly includes E. Harold Davies (brother of Walford, Organist at the Temple Church, London), A. E. Floyd, William Lovelock, Paul Paviour, George Sampson, all of whom published liturgical choral music.

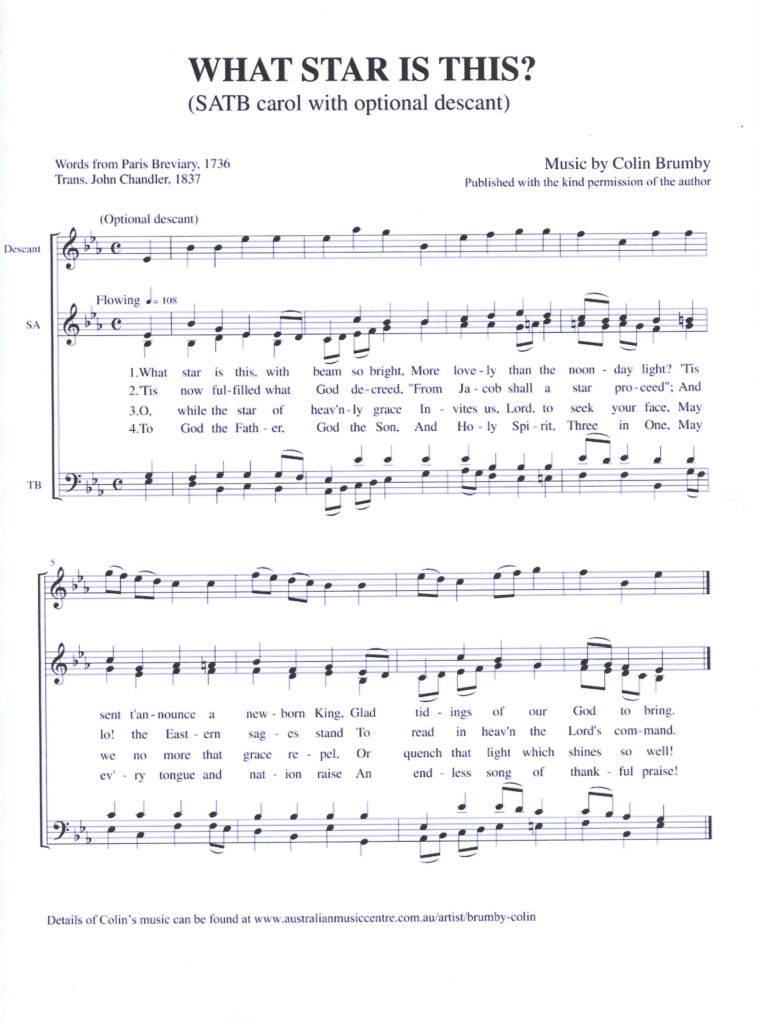

It should be noted that Australia also has a tradition of exporting musicians to the northern hemisphere and in the world of church music Sir William McKie (who as Organist of Westminster Abbey at the time of the Coronation, gave us that wonderful anthem We wait for thy loving kindness O Lord) and Malcolm Williamson (who held the title, Master of the Queens’s Music) are representative of this group. Other composers, although born in Australia, adopt the traditional styles inherited from overseas. Colin Brumby would be the most prolific of this group, one that also includes Rosalie Bonighton, Graeme Morton, John Nickson, June Nixon, and others.

The second category of Australian liturgical music is of more recent origin, and generally comprises musicians who would see themselves firstly as composers, who have usually studied composition, and who identify themselves as Australian. Such composers, at least in their liturgical music, acknowledge tradition yet deliberately incorporate aspects of a compositional language that in some ways can be seen to be uniquely Australian. This group largely stems from the work of Peter Sculthorpe and his contemporaries, who consciously developed an Australian musical language based on the themes of landscape, climate, the music of Indigenous Australians, and Australia’s proximity to Asia.[5] A look at three such works will be illustrative of this category of Australian liturgical music.

When it comes to Christmas much of the recent northern hemisphere music still focuses on aspects of the Christmas narrative (e.g. Jonathan Dove The Three Kings), or returns to ancient sacred texts (e.g. James MacMillan Seinte Mari Moder Milde). In contrast, some of the Australian Christmas music uses reflective and often ambiguous contemporary texts which focus on wonder and intimacy. One of the earliest of Australia’s ‘new’ liturgical works is a short motet by Peter Sculthorpe titled Morning Song of the Christ Child (Faber). The text is by music lecturer and music critic Roger Covell.

The quilted sea is gone like rain, gone and never found again.

A thin three grows in starlit thirst, old and deep and past all hurt.

Green morning sleeps, the sky is sown, kind and calm and all alone.

The poem is wonderfully ambiguous but has subtle resonances for Australians, whose history informs us of sparsely populated deserts and their dry parched landscape, of an ancient inland sea long gone, and the experience of the wonderful transformation of such a landscape into a refreshed green verdant place. Peter Sculthorpe’s simple music supports this sparse poem, with hints of aboriginality in the use of ostinato and drone and a melodic line that avoids driving forward to give direction to the phrase. Like a mirage in the Australian desert the music hovers in one place, reflecting stillness (as known in the Australian outback) and a sparseness and translucency that in some way convey an ‘Australianness’ understood by those who know our landscape and culture.

Matthew Orlovich, who studied with Peter Sculthorpe, has also given us a marvelous and ‘Australian’ Christmas piece in Nativity.

The thin distraction of a spider’s web collects the clear cold drops of night.

Seeds falling on the water spread a rippling target for the light.

The rumour in the ear now murmurs less, the snail draws in its tender horn.

The heart becomes a bare attentiveness, and in that bareness Light is born.

Matthew Orlovich writes of this text

“Nativity is a world of dew drops and spider webs, tender snails’ horns and a bare attentiveness of the heart, a world where everyday things become breathtaking and extraordinary. Guiding us in our observations of these everyday natural wonders, poet James McAuley leads us into a meditative, trance-like state wherein we witness the birth of light”.[6]

(Click on the image to download the full score)

The inner reflection of this gentle poem is the world that Matthew conveys in his musical setting. The lower voices provide a gentle, rhythmic, trance-like pulse which are overlaid with legato phrases in the upper voices, in close harmony, which are almost drone like in the way they extend across the score.

The nature of these two pieces reflect some quite conscious aspects of an Australian musical language, which Peter Sculthorpe has ascribed to the connection between music and place. For Peter (and once articulated, perhaps consciously adopted by other composers who follow) melodic lines in Australian music will often lack drive and direction, and will span a limited melodic range, reflective of the vast flatness and the open expansiveness of the Australian landscape. This may appear to be a somewhat naive and literal connection between music and its environment but for Sculthorpe it is quite deliberate. Peter believes (as quoted by David Matthews) “that Australia is pre-eminently a visual culture, dominated by its landscape. So that, most characteristically, Australian music will be a response to the landscape”.[7] Harmony will also be somewhat static removing from the music the strong sense of propulsion and drive that a strong harmonic rhythm often provides.

A third example of the contrast between recent Australian liturgical music and that of other traditions can be found in Clare Maclean’s We Welcome Summer (Morton Music), a setting of the text of the same name by another iconic Australian poet, Michael Leunig.

We welcome summer and the glorious blessing of light.

We are rich with light, we are loved by the sun.

Let us empty our hearts into the brilliance.

Let us pour our darkness into the glorious forgiving light.

For this loving abundance let us give thanks and offer our joy. Amen.

For a southern hemisphere inhabitant this text offers new theological images not found in traditional liturgical music. This is because the sacred seasons are aligned so closely with the seasons of nature. In Australia a text so full of images of light and brilliant sun replaces more traditional images of starlight in the seasons of Advent and Epiphany since Christmas is at the height of Summer ‘down under’.

The Australian landscape is one characterized by a particular quality of light, and this is another image utilized by composers as well as a metaphor for much that is found in Christian doctrine. Clare Maclean’s setting of this text creates a wonderful luminescence that links this music and its text to New Zealand born Clare Maclean’s adopted home.

In these examples the texts provide a wonderful starting point for the musical language of the composition. But the masses of Ross Edwards and Clare Maclean show that Australian composers will often use a musical language that can be described as Australian even when using traditional sacred texts.

As mentioned above, Peter Sculthorpe has identified that the connection between music and landscape is particularly strong in Australia. If this visual and literal connection exists between and landscape and music in Australia, it also exists between landscape and theology in all traditions. The church has always adopted images from the landscape and the natural world to explore other-worldly ideas. In Australian liturgical music the use of both visual images and literal connections reinforce each other in a most wonderful and unique way.

Peter Sculthorpe, Matthew Orlovich and Clare Maclean are just a few of the composers writing interesting liturgical music in Australia. The reader is encouraged to explore the offerings of Brenton Broadstock, Nigel Butterly, Ross Edwards, Moya Henderson, Stephen Leek, Paul Stanhope, Joseph Twist, and many others whose music deserves much more exposure than it currently receives.

The musical examples from Morning Song of the Christ Child, Nativity and We Welcome Summer can be accessed on YouTube and iTunes. The Australian Music Center is an excellent way to access the music of Australian composers.

[1] Clark, Manning (1962) A History of Australia, abridged version by Michael Cathcart. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press

[2] Gascoigne, John. The Enlightenment and the Origins of European Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003

[3] The 2001 regular church attendees comprised 8.8% of population (Australian National Census) compared with 43% in the USA (Bara Research Group figures for 2004)

[4] Jeffrey Richards Imperialism and Music quoted in Banfield, S. (2007). Towards a History of Music in the British Empire: Three Export Studies. K. Darian-Smith, P. Grimshaw, & S. Macintyre (Eds), Britishness Abroad: Transitional Movements and Imperial Cultures. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press

[5] Roger Covell quoted in Skinner, Graeme. Peter Sculthorpe: The Making of an Australian Composer. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2007

[6] Preface to the unpublished score

[7] Matthews, D. (1989). Peter Sculthorpe at 60. Tempo, 170, 12. Retrieved from http://goo.gl/iUuhJ