The “Sistine” Chapel of Papal Music: between tradition and modernity

Interview with the choirmaster-conductor, Mons. Massimo Palombella

by Andrea Angelini, choral director, composer, ICB director

Andrea Angelini: Considering our times, I’d like you to tell me about the role of sacred music in culture and liturgy: what thoughts and suggestions do you have about the situation in Italy?

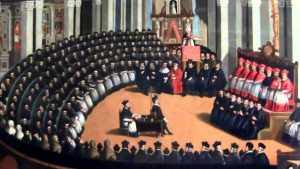

Massimo Palombella: The relationship between culture and liturgy is very interesting because it is exactly what the Second Vatican Council, the last great liturgical reform carried out by the Catholic Church, imposes upon us as a duty; in asking us to enter into dialogue with modernity, the Church wishes, within the musical sphere, to be receptive to music destined for liturgical use, inasmuch as today, it is part of our musical heritage and culture; just think of the advances made in music in the 20th Century, after Wagner, after Mahler… To some degree I believe that the Council is asking us two things: first, that music composed for the liturgy must take account of where we are today and not look backwards; on the other hand is the safeguarding of the Church’s cultural heritage – the origin of Western music – namely Gregorian chant and polyphony. The Council, in asking us to engage with modernity, reminds us not to underestimate the semiological studies undertaken on this subject. Gregorian chant, after the scientific work by Solesmes, which has given us the Graduale Triplex[1], we can no longer think of performing it with the Liber Usualis[2]. With these semiological studies, with everything that is our cultural heritage come down to us at the level of scientific study, whoever performs Renaissance polyphony in the Liturgy has a duty to translate meaningfully the written sign into sound sign. Here, therefore, are the two great challenges which the Second Vatican Council has handed to us, today. In Italy, the Episcopal Conference, to this end, started work a while ago on a massive and important cultural project, the codification of a national repertoire of chants. Basically, they have embarked on processes which will certainly not be appreciated by some, who will complain “Because in the good old days…” If we take a look at history, the Council of Trent also put processes in motion and we know of course who was involved in these processes: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. At that time the Sistine Chapel was the first great realizer of the work of the Council of Trent, with intelligibility of the text: however, it was some years before this liturgical reform became part of the ecclesiastical norm. Therefore, as things stand, we are very close to the Second Vatican Council. I have to say that in Italy some excellent processes for the realization of the Council have been set in train, and these will take a long time to come into effect because it means having to think with a living language, and this means entering automatically into a cultural context which needs to be acknowledged, in addition all the great cultural heritage of the Church will need to be ‘interpreted’ for contemporary times. This will be a long, large project which requires study and research and I am convinced that the Italian Church has started something great from this point of view.

AA: The choral world is often seen as a niche sector, undervalued or criticised. Bearing in the mind Pope Francis’ utterances underlining the need to value the heritage of sacred music and also the attempts to bring it up to date using modern languages, what are your suggestions for educating young people about sacred choral music?

MP: I think that there is a fundamental principle here when we talk of young people and we talk of education: we need to love what young people love because they love what we love. In my own experience – before becoming Choral Director of the Sistine Chapel, I worked in the University where, other than teaching, I also organised a number of pastoral activities including a choir – I never had any difficulty working with young people at a high cultural level. Because a cultural level must be there, meaning that we need the ability to translate our cultural heritage using comprehensible language; fortunately the equation “Lower the level and I’ll get more people” doesn’t work. At the end of the day, the more the teacher or director studies, stays up-to-date, continues their research and makes sure they communicate, the more fascinating the journey will be. When we think “these things are no longer understood, so we’ll leave them out” it’s because we don’t study anymore and also because we don’t study for the love of it. Learning to do it for the love of it, creating respect for things, is a study in itself; we need to explore, make judgements, and making judgements is tricky (because you can get it wrong, as in any experiment), because it is a work that requires you to invest energy. I don’t believe that it is difficult to teach young people about sacred music, like the arts, Latin literature, like educating them in any aspect of basic culture, if this is placed in the context of a discussion, and above all if some message is given to young people, if we are able to create a connection; without a connection, nothing will happen. It is important that big cultural values are always mediated through connections aimed at the growth, maturation and the truth for our young people.

AA: Let’s talk about the Pueri Cantores, who traditionally accompany the liturgy with chant, and also the role of the Schola Cantorum; there are not many of these left. What can be done to retain them, and make them popular above and beyond the church?

MP: There is an international association for Pueri Cantores, we need to be quite clear here however. Why does the Sistine Chapel have Pueri Cantores and a related school, from the third grade of primary to the third grade of secondary school? Why are Pueri Cantores only boys and why are there no girls? Because effectively the, so-called, pure unbroken voice is that of a boy, which will not remain like that forever, but, before it breaks, acquires a series of ‘ambratures’, a group of changes which occur due to physiology, which give that richness of harmonies which a boy choir possesses and a girl choir does not. There is an issue of cultural expectation: if we record with a CD label like Deutsche Grammophon, we are duty-bound to create a product which is aesthetically in keeping. Therefore, I have to record either with falsettos or with boys! This is an important, cultural domain. On the other hand I do believe that teaching singing in general to boys and girls is an excellent pastoral activity which will help them in the future, starting a child off on a discipline which requires choral singing, undertaken at a certain level, will give them a scientific and rigorous way of working which will stand them in good stead for their eventual future employment, as well as in life relationships and in their roles as fathers and mothers. This is the reason why I believe that it is important that we invest culturally in boys and girls with regard to music because music has the dual aspect of being beautiful but of asking a sacrifice, constant hard work so that it can be beautiful. The whole process therefore has an attraction linked to an intrinsic effort, and this process is extremely educative at an impressionable age where being ‘introduced to’ a precise methodology can benefit someone for a lifetime.

AA: Let’s talk about the Cappella Musicale Pontificia ‘Sistina’, which is the world’s longest-running choral group. Over the course of the centuries the Sistine Chapel Choir has been, and remains today, an active participant in all reforms of papal liturgy. What are the responsibilities of such an important role, and what have been the most significant moments of the various activities in which the choir has been involved?

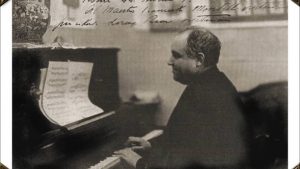

MP: The Sistine Chapel Choir has the same great responsibility of acting in the Church as it did, for example, in the Liturgical Reform of the Council of Trent in the 1600s. This reform was made possible because the Sistine Choir immediately incorporated it into the papal celebrations. To be completely honest, the same cannot be said nowadays of Vatican II, because Domenico Bartolucci – and this year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth – was a man who, as director of the Sistine Choir, categorically opposed the liturgical reform of Vatican II on the grounds of certain unjustified opinions. His cultural closedmindedness unfortunately didn’t allow him to be open to all that was happening in music in that same period, including, therefore, the semiological studies of Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony, along with everything that happened after Verdi. In Bartolucci’s mind, the history of music ended with Verdi. So this has perhaps been a hapax legomenon[3] in the history of the Sistine Choir, in the sense that this was perhaps the first time that the institution did not follow the course of a reform. And in fact at a certain point it became necessary for the Holy See to provide an alternative, because practically they were dealing with an institution that was ecclesiastically, aesthetically and culturally obstructionist. My predecessor, Liberto, really brought this musical association in line with the liturgical reform of Vatican II, but not without great difficulty, because there were still many people who insisted that things had to be done Bartolucci’s way. I had the good fortune to have a predecessor who in some ways was a buffer between Bartolucci and the liturgical reform of Vatican II, which for me was an almost ‘normal’ thing. I am a product of liturgical reform and I am therefore a great believer in it. I believe too that the old music can also benefit from the Vatican II reform; namely, as I said earlier, because of the need to accept the semiological studies and construct an intelligent dialogue with modern thinking. The Sistine Choir therefore has this as its most important task: being responsible first and foremost for implementing the reforms of the Church in the liturgical-musical space. It then, no less importantly, has the responsibility of setting standards for performance practice: our performance of Gregorian Chant or Renaissance polyphony has to be in some way exemplary. That’s not because we are better than anyone else, but because the Sistine Choir is an institution which spends three hours a day almost exclusively studying those two subjects, just as the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia rehearses a set choral symphonic repertoire every day or the Teatro dell’Ópera studies a certain operatic repertoire every day. Moreover, we have the Sistine Choir’s archives at our disposal – the so-called Fondo Cappella Sistina in the Vatican Apostolic Library, which is the world’s largest collection of 15th, 16th and 17th-century liturgical music. All of the repertoire in the catalogue, like what you will hear at the concert this evening, for example, comes from critical editions produced either from manuscripts or from the earliest printed texts. The director of the Sistine Choir must take on this study and research, because if I don’t do it, so much music will go unheard. The responsibility for setting performance practice stems from the fact that the director of the Sistine Choir can draw on the Renaissance arrangements, and can therefore make an interpretation of them which is semiologically and scientifically correct and relevant. This also means being able to “experiment” without worrying about having to put together a motet in order to perform it immediately. Rather, you can try performing a color minor, experiment with how best to interpret a particular rhetorical device… So the Sistine Choir is a sort of ‘laboratory’, if you like! Finally, the Sistine Choir sings at all the celebrations attended by the Pope, but also has a busy concert schedule. Why do we give all these concerts? We don’t travel the world simply for the pleasure of performing a bit of music. We travel so much in order to fulfil an ecclesiastical mandate, that of spreading the Gospel. Each of our concerts is an aesthetic experience, but all of the musical material can be traced back to its original source: the Liturgy. Accordingly, each piece that we perform is always presented, arranged and explained in terms of its historical and liturgical meaning. To attend a Sistine Chapel Choir concert is therefore to participate in an act of faith, an opportunity to experience God. This is why the Sistine Choir agrees to perform concerts.

AA: The Sistine Choir occasionally goes on international tours. Under your direction, it has started to record exclusively with Deutsche Grammophon and won the Echo Klassik prize for its CD ‘Cantante Domino’ (2015). Could you tell us about this experience?

MP: I didn’t approach Deutsche Grammophon; they contacted me because they had become aware that the Sistine Chapel Choir had radically changed its mode of singing. By that I mean that it had moved from a decadent operatic tone which dated from the end of the 19th century to a Renaissance tone, coherent phrasing, and an attempt to create an aesthetic relevant to the material we were performing. It’s the oldest choral institution in the world and has a lot behind it, and this is why Deutsche Grammophon took a gamble on us, in a manner of speaking. They say that they had wanted to collaborate with the organisation in the past, but it had never been possible because of our style of singing, which was very much removed from the Renaissance practice. The recording process was very interesting. We recorded in the Sistine Chapel because we were perhaps the only choral group in the world that could create this complete aesthetic: music from the papal celebrations being performed in the Sistine Chapel, which gave us that perfect acoustic.

AA: So the philological discourse is very important for you, down to considering the aesthetic of the venue and the performance practice…

MP: Yes, absolutely. And this is what lets us record with labels like Deutsche Grammophon. I never considered recording William Byrd because he is stylistically very different to us. For example, when we had to record Allegri’s Miserere, I went looking in the Sistine Chapel’s archive and found Codex 205-206, which was Allegri’s original manuscript. I therefore also tried to position the soloists around the performance space more or less as they would have been according to the records of the papal celebrations of that time. Producing a piece for a recording label like that takes a great deal of scientific, philological and aesthetic consideration.

AA: What comparison would you make with the straight tone used by the English, for example? I’m thinking of the Tallis Scholars, who gave a concert in the Sistine Chapel to celebrate its great restoration and performed Allegri’s ‘Miserere’, amongst other pieces.

MP: The Tallis Scholars are a little removed from our aesthetic for the simple fact that women’s voices are included as well. I believe that the music written to be sung in the Sistine Chapel requires a Renaissance tone. This vocal technique does not incorporate the third register and therefore requires a very covered, precise tone, but with all that Mediterranean warmth that we Italians have in our tone. I believe, for example – and this is my conviction from having studied the manuscripts – that these scores are full of rhetorical devices that were not well recorded in the Baroque period, because while we know a lot about the Baroque period when it comes to performance practice, we know little about the Renaissance. I believe that Renaissance music is a synthesis of rhetorical devices, tension and release that requires continuous use of the messa di voce technique. It is in and of itself a very lively music, and so I believe that to sing it straight is to treat it like 15th-century music. I can understand singing Dufay or Despresz that way, because then the text was often a ‘pretext’ for counterpoint. When we recorded a Dufay piece and a Desprez piece, we sang them as if we were musical instruments, because that was the composers’ intention, rather than giving attention to the text. There is a great shift when we enter the High Renaissance, where at a certain point the text became the foundation on which the music was based. In parallel to the text, there are the rhetorical devices of tension and release; a great deal of tension is given to words and phrases. I believe that all of this is encoded in the DNA of the music written for the Sistine Chapel, for the papal celebrations. After all, it’s enough to admire Michelangelo’s paintings to realise that the Renaissance was in no way an uninteresting period of history. All of it must absolutely be filtered by reason, by a formidable intelligence: messe di voce, tension, release, colores minores, hocket[4]… So everything must be filtered through profound reasoning, by a deep, almost ‘maniacal’ command of everything that was typical and characteristic of the Renaissance.

AA: Can you accept the proposal of a voce ferma performance with the only purpose being that of experiencing a different aesthetic, aware, however, of not being within the sphere of philological reproduction but a different aesthetic pleasure?

MP: Yes, absolutely. It can be done, nobody forbids it. However, I believe that is like removing the salt and pepper from this music, in the sense that it is harmonically poor music. If the choir also does not highlight the word… The Renaissance was a characteristic historical period, which gave the same attention to the counterpoint as to the word. So, if the choir does not pay the same attention, the performance becomes incredibly dry.

AA: You could argue that even the music of Arvo Pärt, constructed using the tintinnabuli technique, has a very simple harmony that does not require the type of attention and vocal style that we talked about before. Here maybe there is the pursuit of the pleasure of contemplation in the voce ferma and maybe the English groups are attempting to bring this experimentation to Renaissance music.

MP: Yes, my belief is that the success for these English bands in the ’80s and ’90s was basically due to the fact that those who should have done this philological work never did it! The Sistine Chapel didn’t really do it. With Deutsche Grammophon we have now recorded the Missa Papae Marcelli by Palestrina, which was previously unheard of: there are so many recorded that I told myself ‘ether we record a version that is truely different or we do not record it at all’. It was a huge philological work because I had to retrieve the 1567 edition, thus deciding not to add the Agnus Dei II because it is not by Palestrina. Although although it is in the 18 codex of Santa Maria Maggiore, in the 22 codex of the Sistine Chapel, when Palestrina published the second book of Masses in 1567 it was not included, and in 1599, when a posthumous edition was published, the publisher did not included it and wrote Agnus Dei secundus dicitur ut supra primus. The colores minores, the problem of too many beats, the problem of rhetorical figures, of the tactus consistent with the writing of the composer … It was a very demanding job to obtain a correct philological product, at the height of the institution that owns the manuscripts and that really say something new, explaining the reasons in the booklet that accompanies the CD; I agree with the fact that a choral group can have the aesthetic pleasure of implementing what you say, but our job is to perform this kind of music by it giving a plausible, verified, scientific, obviously debatable, but reasoned and profoundly researched interpretation today.

AA: Music is the language of the spirit. Your secret current vibrates between the heart of those who sing and the soul of the listener; these are the words of Kahlil Gibran. What is the role of the choirmaster in all of this?

MP: The choirmaster has a very important role in my opinion. His first role is to be a person who studies and researches and then, secondly, he has the role of becoming, little by little, invisible. The music is made to be harmonised and not to be direct. In general, and this is a great tradition, the Renaissance music was not live; everyone read from a central book unless someone took on the task of the directing as we now understand it.

AA: In St Mark’s Cathedral there was probably a figure who was at the centre of the apse, behind the altar, to solve the execution problems caused by the double choir …

MP: The role of the director is create a good harmony. But the real role of choir director, and believe me that the choristers realise this, is to be a person who studies, who researches and who requests of the choristers slightly less than he does himself; you can’t ask choral singers things that the director does not, he must be the first to set the example. My choristers spend three hours in personal study and three more hours as a choir. So I have to study at least six hours a day, but I study more, because then there is the research and much more … This issue in relation to the music to be performed; second problem, in my case, as maestro-director, is that I also have to compose. The maestro-director of this institution, the maestro of the Sistine Chapel, first of all should not be defined, in my opinion, as was done with Bartolucci, as ‘just’ a composer. The maestro of the Sistine Chapel is ‘also’ a composer, but he is, as we have seen above, responsible for the cultural heritage of the Church; so he has to be an expert and a scholar of early music and must translated with relevance the written sign into sound. Where composing is concerned, the maestro of the Sistine Chapel must look forward. He must do as Palestrina did, as Lorenzo Perosi did. At the beginning of the 20th century, the latter brought the Sistine Chapel out of where it had relegated by Domenico Mustafà, writing only Palestrina-style with counterpoints. Perosi dared not to write Palestrina-style, profoundly experiencing his historical moment. So I believe that the maestro of the Sistine Chapel should be a man who, in his compositional gesture, lives in the present and who, after Wagner, after Mahler, lets himself be challenged by everything that has happened in music. The compositional gesture of the maestro of the Sistine Chapel must be a gesture that takes account of where he now lives: he should write for today’s audience and not for the Renaissance audience. Those who do my job must pay attention to their time, be passionate about modern music, about contemporary music and experimental music, must think highly of his colleagues and therefore be curious and listen to music composed and performed by others and not simply read Palestrina and his music. This is important because the maestro-director must be able to combine the audibility and intelligibility of music with modernity. I think this is, at the moment, the great challenge that awaits us.

Mons. Massimo Palombella was born in Turin on 25 December 1967. He was ordained a priest of the Salesian Congregation on 7 September 1996. He studied philosophy and theology, receiving his doctorate in dogmatic theology, and he studied music with Luigi Molfino, Valentin Miserachs Grau, Gabriele Arrigo and Alexander Ruo Rui, graduating in choral music and composition. Founder and maestro-director of the Inter-University Choir of Rome, he worked in the university parish of the Diocese of Rome from 1995 to 2010, taking care, as the maestro of music, of all the meetings of the Holy Father with the University culture. He was a lecturer until 2011 at the Pontifical Salesian University, Faculty of theology, music and liturgy and teaches at the Conservatory Guido Cantelli of Novara, to students specialising in sacred music, liturgical composition, Roman polyphony and legislation of sacred music. He was also a professor of musical languages at La Sapienza University in Rome and at the Conservatory of Turin and at the Pontifical Institute of sacred music in Urbe he taught liturgy. From 1998 to 2010 he directed the liturgical music magazine Armonia di Voci, by teh publisher ElleDiCi. On 16 October 2010 he was appointed maestro-director of the Sistine Chapel Pontifical Chorus by Pope Benedict XVI and reconfirmed in 2015 by Pope Francis. He is a member, as an expert, of the National Liturgical Office Council of the Italian Bishops Conference. On 14 January 2017 Pope Francis appointed him Consultor of the Congregation for divine worship and the discipline of the sacraments. With both the University Choir of Rome, which he directed until 2011, and with the Sistine Chapel Pontifical Chorus he has performed many concerts in Italy and in the world and has recorded a large number of CD and DVDs with ElleDiCi, Libreria Editrice Vaticana and Deutsche Grammophon, with whom he won the prestigious Echo Klassik Award for the CD ‘Cantate Domino’. Email: info@cappellamusicalepontificia.va

Translated by Laura Massey (UK), Karen Bradberry (Australia) and Mirella Biagi (UK-Italy)

[1] The Gradual Triplex is a liturgical text which contains the mass chants of the Gregorian repertoire. It was published in 1979 and has been reprinted continuously by the Abbey of Solesmes under official mandate of the Catholic Church.

[2] The Liber usualis Missae et Officii, more usually known as the Liber usualis, is a liturgical text which contains a collection of Gregorian chants which are not just used by the Roman Catholic Church. The texts and melody of the chants are transcribed in single square notation. The first edition appeared in 1896, published by the monks of the Abbey of Solesmes. A number of editions followed and since the Second Vatican Council no new editions have appeared. The Liber Usualis is popular in Latin around the world, even though it has now been supplanted by the more up-to-date Gradual Triplex which, as well as the square notation, also includes transcriptions of the St Gall and Laon notations in the repertoire and in which the selection of passages is more considered.

[3] In linguistics and philology, a hapax legomenon (often called simply a hapax or, less commonly, apax; plural hapax legomena or hapax legomenoi), from the Greek ἅπαξ λεγόμενον (hápax legómenon, “said only once”) refers to a word or expression that is only used once in a text, by an author or in the entire literary sphere of a language

[4] Polyphonic device especially diffuse in France between the 11th and 12th centuries. Characterised by rapid alternation of the voices by means of pauses between syllables (and with an attempt at counterpoint between them) so to create a ‘sobbing’ effect.