Sakrileg oder Geniestreich?

Beethovens Instrumentalwerke textiert

Von Sven Hiemke

Für Puristen ein Gräuel: Beethovens Instrumentalwerke – textiert! Doch was bei manchem scheinbar Kundigen nur ein Naserümpfen hervorrufen mag, hat eine lange Tradition. Die ersten Chorbearbeitungen von Beethovens Musik stammen bereits von unmittelbaren Zeitgenossen. Ignaz von Seyfried beispielsweise, ein Freund Beethovens und seines Zeichens Kapellmeister und Hauskomponist am Theater an der Wien, richtete Drei Equale für vier Posaunen als Sätze für Männerchor ein und unterlegte sie mit Texten aus dem Psalter und von Franz Grillparzer; zwei von ihnen erklangen unter anderem zu Beethovens Begräbnis. Seyfrieds Breslauer Kollege Gottlob Benedict Bierey bearbeitete den 1. Satz von Beethovens sogenannter „Mondscheinsonate“ zu einem Kyrie und den 2. Satz von dessen 5. Klaviersonate zu einem Agnus Dei (beide für vierstimmig gemischten Chor und Orchester).

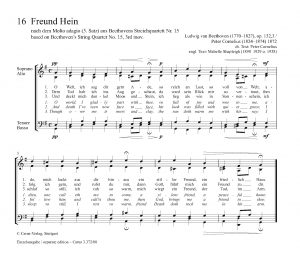

Mit der Wahl geistlicher bzw. liturgischer Texte schien sich religiöses Empfinden geradezu selbstverständlich mit Beethovens Musik zu verbinden. Doch wurden auch andere lyrische Texte herangezogen, um den Ausdrucksgehalt kantabler langsamer Sätze Beethovens stimmig aufzunehmen. So wurde das Adagio der 7. Violinsonate mit der Bearbeitung von Hans Georg Nägeli zum Tränentrost. Und Peter Cornelius kombinierte den choralähnlichen dritten Satz des Streichquartetts op. 132 – den Beethoven selbst mit der Überschrift „Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit“ gekennzeichnet hatte – mit seinem Gedicht Freund Hein.

Eine Anmaßung? Allzu häufig wird bei einer solchen Einschätzung ausgeblendet, dass Begriffe wie „Originalkomposition“ oder „musikalische Authentizität“ erst im 20. Jahrhundert entstanden sind. In früheren Zeiten dachte man über Bearbeitungen noch ganz anders. Anpassung an einen anderen Aufführungsrahmen oder veränderte Hörgewohnheiten, Modernisierung, Wiederbelebung, Verbreitung, Erleichterung des Zugangs, Verdeutlichung, Ausdruckssteigerung: Dies waren nur einige der Gründe, die zu Arrangements allerlei Art motivierten. Und auch Beethoven selbst fertigte Bearbeitungen eigener und fremder Werke an. Bisweilen waren Bearbeitungen auch pädagogisch motiviert: Um Beethovens Themen auch jenen Musikfreunden nahezubringen, die keine Gelegenheit hatten, diese Werke im Original zu hören, unterlegte der Tübinger Musikdirektor Friedrich Silcher ein Thema der Appassionata mit einem Text von Friedrich von Matthisson, einem von Beethoven geschätzten Dichter, und veröffentlichte diese Hymne an die Nacht 1830 zusammen mit elf weiteren Bearbeitungen unter dem Titel Melodien aus Beethovens Sonaten und Sinfonien zu Liedern für eine Singstimme eingerichtet. Gut 30 Jahre später wurde Silchers Bearbeitung von Ignaz Heim für vierstimmigen Männerchor adaptiert; in einer Fassung für gemischten Chor ist sie nun in Jan Schumachers Chorbuch Beethoven (Carus 4.025) erschienen. Ein weiteres Stück aus diesem Chorbuch, der Persische Nachtgesang, war Silchers Beitrag für das Beethoven-Album. Ein Gedenkbuch dankbarer Liebe und Verehrung für den großen Todten, an dem sich 150 Persönlichkeiten aus ganz Europa beteiligten. Das Stück verbindet den „Gesang der Peri“ aus den Bildern des Orients von Heinrich Wilhelm Stieglitz mit dem langsamen Satz aus Beethovens 7. Symphonie. Der schreitende Rhythmus wird dabei zu einer Art wiegender Beschwörungsformel.

Nicht dass jede Bearbeitung eines beliebigen Werkes a priori ein Gewinn wäre. Doch bei Bearbeitungen von Beethovens Sololiedern und sogar Instrumentalwerken für Chor belegt bereits die große Anzahl an Arrangements die Kantabilität, die diesen Stücken innewohnt. Manche Bearbeitungen klingen, als sei die Verbindung von Text und Musik schon immer da gewesen: Als sei Beethoven etwa zu der wunderbar expressiven Cavatina seines Streichquartetts op. 130 erst durch den Text des 121. Psalms („Ich hebe meine Augen auf“), den Heribert Breuer im 21. Jahrhundert dieser Musik unterlegt hat, inspiriert worden, als erkläre sich das durch seinen Wegbegleiter Karl Holz überlieferte Eingeständnis des Komponisten, diesen Satz „unter Thränen der Wehmuth komponirt“ zu haben, in dem Ausdrucksgehalt des Psalmtextes.

Tatsächlich enthüllen solche Bearbeitungen bisweilen Aspekte der Komposition, die vorher verborgen waren. Dies gilt auch für viele Anverwandlungen, die heutige Bearbeiter zu Einrichtungen für Chor inspiriert haben – von Beethovens Klavier- über Streichquartett- bis hin zu Symphoniesätzen. Gemeinsam eröffnen diese Arrangements dem Interpreten die Möglichkeit, sich mit dieser Musik auf neue (alte) Weise singend auseinanderzusetzen, dem unvoreingenommenen Hörer eine originelle Form der Unterhaltung – und allen Beteiligten eine lebendige, schöpferische Bereicherung.

Prof. Dr. Sven Hiemke studierte Musikwissenschaft und Kirchenmusik in Hamburg, wo er 1994 mit einer Arbeit über die Bach-Rezeption Charles-Marie Widors promoviert wurde. Seit 1996 ist er Professor für Musikwissenschaft an der Hochschule für Musik in Hamburg. Zwischenzeitlich übernahm er auch Lehrstuhlvertretungen an der Universität Kassel und der Hochschule Vechta und war bis 2006 auch als Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter im Bach-Institut Göttingen tätig. Er wirkt als Lektor, Übersetzer, Editor und Musikkritiker und ist Autor etlicher Aufsatz- und Buchveröffentlichungen. Der Schwerpunkt seiner Veröffentlichungen liegt auf geistlicher Musik vom 18. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert. E-Mail: sven.hiemke@t-online.de