A Short History of Czech Choral Music

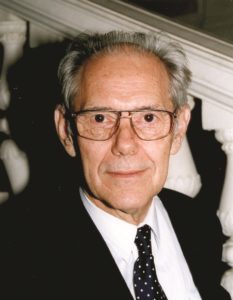

Stanislav Pecháček, choral conductor and teacher

Choral singing has played a very important role in the life of Czech society since medieval times and has been connected mostly with Christian liturgy for hundreds of years. It was not restricted just to performance of Gregorian chant, as its repertory also included various forms of polyphonic music. The vocal polyphony flourished especially in our country during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially in the practice of ‘literátská bratrstva’ (brotherhoods of intellectuals), the townsmen’s organizations responsible for music in churches. The most important composer of the time was Kryštof Harant z Polžic a Bezdružic (1564–1621), the author of the Mass Missa quinis vocibus, a parody based on a cantus firmus from Luca Marenzio’s madrigal Dolorosi Martir.

Churches remained the main location for music performances until the end of the eighteenth century, which is why most of the vocal-instrumental pieces were connected with liturgy. There is an enormous production, represented by different kinds of Masses, Vespers, Litanies, Psalms and other pieces on liturgical texts (Salve Regina, Magnificat, Te Deum etc.). Music was also produced at noble residences. The rich nobility built their own orchestras, mostly from musically talented servants. They concentrated on instrumental music which would be heard not at concerts but at everyday or special occasions, such as weddings, funerals, dancing and feasting. The productions had very little in common with the character of concerts where music is performed exclusively for listening and there is no participation by the audience. The repertoire also included secular cantatas, composed for birthdays, name-days, marriages, deaths, or births of children in the family of the employer.

Czech composers who lived in Bohemia were mostly connected with churches. Adam Michna z Otradovic (1600–1676), poet and outstanding composer of the early Baroque, was the town organist in Jindřichův Hradec. He became famous for his simple vernacular hymns Česká mariánská muzika (Czech Marian music), Svatoroční muzika (Music for the liturgical year) and Loutna česká (The Czech lute). At the same time, Bohuslav Matěj Černohorský (1684–1742) worked as an organist at St Jakub in the Old Town of Prague, and also for some years in Assisi and Padua (Italy). His offertory, Laudetur Jesus Christus, is considered today to be one of the best works of Czech polyphony. František Xaver Brixi (1732–1771) was appointed Kapellmeister of St Vít Cathedral in Prague and thus attained the highest musical position in the city. His tremendous output of approximately 500 works contains about 120 masses. Josef Seger (1716–1782) was appointed organist of the Týn church in Prague. His numerous compositions, comprising Masses and other liturgical pieces, reflect stylistic features of late Baroque.

A special group of Czech musicians was made up of country teachers, whose duty was also to organise music for the churches. Among them, the best known are Jakub Jan Ryba (1765–1815), the author of the very popular Christmas Mass Hej, mistře, and Karel Blažej Kopřiva (1756–1785), who belonged to the group of teachers, musicians and composers in the small village of Citoliby.

Many Czech musicians found employment abroad. Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679–1745), the major Czech composer of the late Baroque, was a double-bass player, conductor and composer in the Roman Catholic Royal Chapel in Dresden. His works include about twenty Masses and many other liturgical pieces. Josef Mysliveček (1737–1781) lived in Italy, František Xaver Richter (1709–1789) in Germany and France, Antonín Rejcha (1770–1836) in Paris. Many Czech composers worked in Vienna, the capital of the Austrian empire where a number of them made a notable career: Leopold Koželuh (1747–1818), František Ignác Tůma (1704–1774), Jan Křtitel Vaňhal (1739–1813), Antonín Vranický (1761–1820), Pavel Vranický (1756–1808).

The beginning of secular choral singing in Bohemia dates only from the 19th century; at this time secular choral compositions began to appear for these new choirs. After modest beginnings, the great composers appeared in the second half of the century. Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884), the founder of Czech national music, was the first among them. He was the author of several pieces for male-voice choirs: Tři jezdci (The Three Riders), Rolnická (Farming), Píseň na moři (Song of the Sea), of three pieces for female-voice choirs, still very popular are Má hvězda (My Star), Přiletěly vlaštovičky (Return of the Swallows), Západ slunce (The Sunset), and of a cantata Česká píseň (Czech Song).

His successor Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) enriched Czech choral music with many compositions written to accompany folk poetry, such as Moravské dvojzpěvy,( Moravian duets) and with several spiritual and secular cantatas: Stabat mater, Requiem, Te Deum, Svatební košile (The Spectre’s Bride), among others.

Czech choral singing reached a new qualitative level at the beginning of the twentieth century thanks to the choral teacher associations in which artistic quality took precedence over the prevailing social function, and the new technique appeared also among choral works. The very numerous works of Josef Bohuslav Foerster (1859–1951) can be named as a typical example.

Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) focused with his male-voice choirs on the poems by Petr Bezruč Kantor Halfar (Halfar the Schoolmaster), Maryčka Magdónova and Sedmdesát tisíc (Seventy Thousand), which dealt with social and national problems in Silesian in a very realistic way. His cantatas, especially Glagolská mše (Glagolitic Mass) belong to the most important Czech compositions of that time. Josef Suk (1874–1935), especially with his cycle Deset zpěvů (Ten Songs) for female-voice choir, and Vítězslav Novák (1870–1949) are other important composers who lived between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

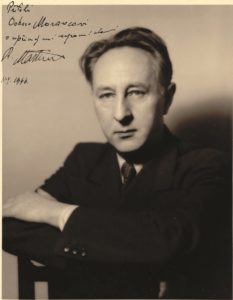

Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959) is the most famous Czech composer, world-wide, of the first half of the twentieth century. Although he spent most of his life abroad (France, USA, Switzerland, Italy), the majority of his choral compositions were written on Czech folk poetry, such as Česká říkadla (Czech Nursery Rhymes), three cycles of Czech madrigals and others. He also composed cantatas inspired by biblical and ancient texts and passages from modern world literature. The tendency to use short pieces and a chamber formation are typical of Martinů’s cantatas as well, examples include Kytice (Garland), Polní mše (Field Mass), Hora tří světel (Mount of Three Lights), Gilgameš (The Epic of Gilgamesh). His chamber cantata Otvírání studánek (The Opening of the Wells) is one of the most popular compositions in twentieth-century Czech music.

Among modern Czech composers Petr Eben (1929–2007) stands out. His large output was inspired partly by folk songs, their arrangements and his own pieces on folk poetry, for instance O vlaštovkách a dívkách (Swallows and Maidens) for women’s choir or Láska a smrt (Love and Death) for mixed choir, and partly by ancient and medieval texts, e.g. Řecký slovník (Greek Dictionary), Cantico delle creature, Apologia Sokratus, Pragensia, Pocta Karlu IV (Honour to Charles IV). He also wrote many pieces for children´s choirs, e.g. Zelená se snítka (The Spring in Leaf) or Deset dětských duet (Ten Children’s Duets). The most important inspiration for him was his deep belief in God which is manifested in many Masses and other liturgical pieces, including Posvátná znamení (Sacred Symbols).

Also, compositions by Zdeněk Lukáš (1928–2007) are very popular among Czech choirs of every type and level. Lukáš very often sets folk poetry to music, like Jaro se otvírá (The Spring Begins) for male-voice choir, Věneček (The Wreath) for girls’ choir. He also was inspired by ancient and medieval texts and wrote several liturgical pieces (Requiem, Missa brevis).

Among composers of the older generation we must mention also Antonín Tučapský (1928), who lived for many decades in London, Otmar Mácha (1922–2006), Ilja Hurník (1922), Zdeněk Šesták (1925) and Jiří Laburda (1931).

At the beginning of the new millennium choral production by Czech composers was very rich. One of the most important reasons is that choirs have a tendency to perform new compositions, both by foreign and Czech composers, unlike instrumental groups whose repertoire is mostly based on classical music. This is why many choral composers come from the middle and younger generation.

Edited by Will Masters, UK, and Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy