El canto en el niño es un Derecho Humano (Segunda parte de 3)

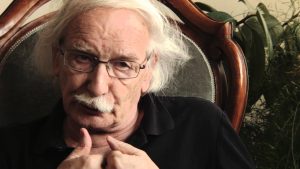

Oscar Escalada, director coral, compositor y profesor

El canto en el niño es un Derecho Humano (Primera parte)

Empatía“Take that boy on the street. Teach him to blow a horn, and he’ll never blow a safe.”

(Tome ese chico de la calle, enséñele a soplar un corno, y nunca volará una caja fuerte.)

De la comedia musical The Music Man, 1958.

Aristóteles afirmaba que “el ser humano es político, esto es, social: vive en familias, clanes o grupos llamadas aldeas, pueblos, ciudades o naciones, y siente necesidad de juntarse con otros semejantes para poder realizarse como tal.” Estaba en lo cierto y pudo ser apoyado por los estudios científicos desarrollados a través de la historia hasta nuestros días.

La ciencia ha demostrado fehacientemente que el ser humano no nace ni bueno ni malo: nace con unas propensiones o unas tendencias que pueden conducir a una agresividad y a un comportamiento explotador de los demás si no se canalizan bien. [1]

A fines de 1980 el neurobiólogo italiano Giacomo Rizzolatti de la Universidad de Parma, Italia, descubrió que hay unas neuronas especializadas en reconocerse en el otro a las que llamó neuronas espejo[2]. Fueron llamadas así porque la neurona reproduce en el observador la misma actividad neural que se produce en el actor correspondiendo a la acción manifestada, pero sin realizar la conducta de manera externa. Es decir, en el observador es sólo una representación mental de la acción del actor.

Las neuronas espejo explicarían cómo podemos acceder a las mentes de otros y entenderlas, y hacen posible que se dé la intersubjetividad, facilitando de este modo la conducta social.

Estas neuronas son las responsables de nuestra vida social y son sumamente activas en la niñez, ya que participan en el aprendizaje por imitación. Permiten que se reproduzca en nuestro cerebro lo que otra persona está haciendo.

Se trata de una compleja forma de inferencia psicológica en la que la observación, la memoria, el conocimiento y el razonamiento se combinan para poder comprender los pensamientos y sentimientos de los demás. A este proceso cognitivo, racional y emocional lo llamamos empatía.

Las neuronas espejo están relacionadas directamente con la conducta humana. Según Moya-Albiol[3] la empatía presenta tres componentes diferentes:

- Cognitivo: Conocer los sentimientos de otra persona.

- Emocional: Sentir lo que está sintiendo, de forma similar o igual a lo que el sujeto puede sentir en la misma situación.

- Social: Responder compasivamente a los problemas que le aquejan.

“La respuesta empática incluye la capacidad para comprender al otro y ponerse en su lugar a partir de lo que se observa, de la información verbal o de la información accesible desde la memoria (toma de perspectiva), y la reacción afectiva de compartir su estado emocional, que puede producir tristeza, malestar o ansiedad.”

Según las investigaciones del Dr. Jean Decety de la Universidad de Chicago[4], esta capacidad de nuestra especie tiene connotaciones sociales que se desarrollan desde el nacimiento. La percepción de las relaciones humanas empieza a estar presente entre la madre y el hijo, y es allí donde se generan los primeros pasos de este desarrollo. Por lo tanto, el individuo imitará de su medio social los parámetros que su cultura conlleva y al imitarlos se irá asociando a sus congéneres adaptando su conducta a ella. Si esta relación se produce inadecuadamente por tratarse de familias disfuncionales en medios sociales adversos, lo que se aprenda será lo que las neuronas espejo hayan recibido como información. Las neuronas espejo imitan la acción observada.

Dos episodios relevantes tuvieron lugar en 1993 en Liverpool, Inglaterra, y en 2007 en Maldonado, Uruguay, que ayudaron a comprender el fenómeno de la existencia de la empatía y las neuronas espejo como elemento de control en las relaciones humanas ya que, como acabamos de ver, las neuronas espejo tienen la capacidad de imitar lo aprendido socialmente.

Estos episodios tuvieron como protagonistas a niños de entre 10 y 14 años de edad, y las características de los mismos eran similares: tres niños, dos de los cuales mataron al tercero y continuaron jugando como si el episodio no hubiese ocurrido. Las descripciones de ambos casos no tienen relevancia en este trabajo pero sí el hecho de haber sido perpetrados por niños de similares edades y haber tenido la misma actitud frente al hecho aberrante.

En el caso de los niños ingleses, la decisión del juez establece que los niños eran conscientes de lo que estaban haciendo, sin embargo no tuvieron ningún remordimiento, sólo intentaron disimular el hecho como un accidente de tren pero luego continuaron con sus juegos.

En ambos casos se dio una constante: los niños tuvieron una infancia problemática, provenían de familias disfuncionales con dramas de alcoholismo y violencia familiar. Por su conducta problemática eran rechazados por las personas de su medio y debían valerse por sí mismos, muchas veces en situación de calle desde temprana edad.

A partir de estas coincidencias y el descubrimiento del Dr. Rizzolatti, los investigadores coincidieron que la razón de la falta de remordimiento y de no sentir los episodios como aberrantes se debió a la falta de desarrollo de las neuronas espejo en el sentido de una familia, de afectos compartidos, atribuyéndosele la reproducción de su infancia problemática y carente de afectos.

Los niños ingleses fueron juzgados como adultos y sentenciados a cadena perpetua. Los psicólogos que trataron a estos niños durante su cautiverio, luego de pasados muchos años de cárcel, lograron que pudieran sentir el horror de lo que habían hecho y su conducta se modificó a tal punto que luego de ocho años se les otorgó la libertad condicional por buena conducta. No obstante, un par de años después, uno de ellos volvió a la cárcel por distribuir pornografía infantil.

No se tiene conocimiento de estudios que se hayan realizado a los niños uruguayos.

La importancia del descubrimiento de las neuronas espejo se manifiesta en estas historias que llegan al límite de los actos humanos y los muestran descarnadamente. Indudablemente la gradación de los episodios que puedan ser muestra de ello reflejará conductas diversas que no necesariamente tienen que llegar a tal nivel de aberración. Pero sí son muestras de la importancia que tienen cuando fallan o no están desarrolladas.

En ese sentido la actividad coral infantil puede ser una herramienta eficaz en la moderación de la agresividad en la sociedad moderna, ya que tiene las condiciones necesarias para desarrollar la empatía y permitir que el afecto pueda presentarse, incluso en niños de características similares a los mencionados más arriba.

El canto coral desarrolla un gran sentido de pertenencia al grupo, contiene a sus miembros afectivamente, la sociedad los reconoce y se sienten aceptados por ella a través del aplauso que reciben en cada concierto, pero ese aplauso proviene de la expresión artística, estética, o sea de los sentimientos expresados, y permite mostrarse al individuo a sí mismo como ser sensible sin menoscabo de ello. Por el contrario, precisamente mostrando su sensibilidad es que recibió el aplauso.

De igual manera, la sociabilización se desarrolla de modo espontáneo. Todos los miembros del coro tienen y cumplen una importante función y se esfuerzan en pos de un objetivo común.

Las características de equipo y familia que describen Mary Alice y Gary Stollak[5] son precisamente las que apoyan esta hipótesis. Es importante destacar que Mary Alice Stollak es directora de coros de niños en East Lancing, Michigan, y que Gary Stollak, su esposo, es psiquiatra especializado en familia y Profesor en la Universidad del Estado de Michigan. Según consta en su trabajo, el resultado de su investigación “sugiere que el individuo, más que sentirse miembro de un equipo, se siente miembro de una familia. Desde luego que cada coro, al igual que cada familia, enfrentarán situaciones estresantes y problemáticas (…). No obstante, estas situaciones pueden ser beneficiosas ulteriormente para el desenvolvimiento satisfactorio del coro.”

Es importante esta aseveración, ya que conlleva la perspectiva del reconocimiento interpersonal. El coro tiene esa característica de generar la necesidad de una labor común entre sus miembros, lo que lo equipararía a un equipo. Pero al equipo, habitualmente lo que lo une es el esfuerzo por vencer a un contrincante. No ocurre esto en el coro, no hay contrincante a quien vencer. Quiere decir que el trabajo en equipo se produce por otras razones muy diferentes a las de la competencia entre equipos como puede suceder en el fútbol, rugby, hockey o cualquier otro “juego de guerra en tiempo de paz”, como se la define a la contienda deportiva. Lo que se busca es mostrar un resultado que sí es producto de la labor conjunta de sus individuos, pero un resultado estético, sensible, que se expresa a través de lo espiritual del ser humano.

La aceptación que tiene esa actividad con el aplauso de la audiencia, es la manifestación de afecto y agradecimiento por la oferta sensitiva, estremecedora, conmovedora o vibrante que ha nacido de la comunicación entre el público y el coro. En el individuo que recibe el aplauso, la aceptación de su comunidad frente a lo que él ofrece ayuda a reafirmarle su autoestima, es apreciado. La idea de familia que plantea el matrimonio Stollak es de gran importancia en este contexto ya que implica que a pesar de que en una familia “enfrentarán situaciones estresantes y problemáticas”, también reciben afecto.

El arte requiere de la complicidad del público o del lector y el arte temporal como lo es la música, la literatura o el teatro, no escapa a esa regla. Ese público puede estar formado por la familia de los coristas, gente con la cual se ven y tratan cotidianamente. Sin embargo, en el momento del concierto se produce una instancia de juego. Todos juegan su rol: los familiares “juegan” a que son público y en el escenario sus niños “juegan” a ser artistas.

Esto también es aplicable a cualquier otra manifestación artística que no necesariamente involucre a los niños y sus familiares. Una obra de teatro de William Shakespeare representada en The Globe Theatre de Londres por Sir Laurence Olivier y la Royal National Theatre Company[6] también necesita de la complicidad del público. No sería posible sin ella la actuación. Todo el mundo sabe que lo que está viendo cuando Otelo mata a Desdemona no es un crimen sino una ficción. Sin embargo, aunque se conozca el argumento antes del inicio de la obra, el público se sentirá consternado, alegre, triste, o se conmoverá de diversas formas frente a un hecho que en la realidad no está sucediendo.

Esa complicidad es la misma que se requiere frente a grandes o pequeños artistas. No importa que cuando concluya el concierto se busquen, vayan a tomar algo y sigan su rutina familiar habitual. Es en ese momento, casi mágico, que el niño es un artista y su mamá o papá es parte del público. Lo interesante es que ese juego funciona así y sus reglas son simples: uno canta en el escenario y el otro escucha en la platea. Pero en ese momento quien escucha no está solo, sentado en el sillón de su casa, sino que está rodeado de otra gente en un lugar en el que van a dedicar un tiempo para deleitarse. El deleite es una sensación que esperan percibir a través de la acción de sus hijos, de su canto, y se preparan para ello al igual que sus hijos se prepararon para cantar lo mejor que saben. Ese momento es la recompensa de ambos y es la capacidad que tiene el arte para movilizar los afectos, esos que les faltaron a los niños ingleses y a los uruguayos.

Niños en situación de calle pueden ser incluidos sin necesidad de ninguna actividad previa ya que el canto está utilizando su instrumento idiosincrático como es la voz. Sólo tienen que tener la oportunidad de aprender a usarla.

Maud Hickey es una Profesora de la Universidad Northwestern de los EE.UU. Ella está integrada en un programa para jóvenes delincuentes encarcelados. Ha desarrollado un interesantísimo informe del cual tomo un párrafo:

“La investigación sobre la eficacia de la educación artística en los centros de detención es escasa pero creciente. En el Manual de Oxford recientemente publicado de la Justicia Social en Educación Musical, mi crítica de la literatura de investigación sobre los programas de música en los centros de detenciones encontró que los programas de música producen resultados psicológicos extramusicales, como la mejora de la confianza y la autoestima, mejora en la capacidad de aprendizaje, así como un mejor comportamiento y la reducción de la reincidencia.”[7]

No es novedosa tampoco la utilización del canto coral como terapéutica contra la adicción a las drogas y al alcohol. Ya he mencionado en mi libro anterior al Minnesota Adult & Teen Challenge Institute. Esta institución tiene sedes en Twin Cities, Brainerd, Duluth, Rochester y Buffalo en los EE.UU., y tiene varios programas para pacientes externos e internos. Hay programas de corto tiempo -entre 30 y 60 días- y de largo tiempo -entre 13 y 15 meses-. Todos los programas están disponibles para jóvenes y adultos, mujeres y varones. Un día típico incluye: tareas, capilla, comidas, período de estudio, práctica de coro, clases, tiempo libre y devociones. En los programas de larga duración la práctica coral es obligatoria “sepas cantar o no” tomando las palabras de su Director Sam Anderson. Si bien es una institución religiosa y su programa coral incluye la participación del coro cada domingo en una iglesia diferente de la región, la base científica de su actividad es congruente con una institución secular también. La ventaja del programa en las iglesias es que los individuos cantan “sepan o no sus canciones” todos los domingos. Pero esto también se puede montar sobre un programa que tenga conciertos semanales, por ejemplo en clubes, en hogares para ancianos, comedores populares e instituciones intermedias organizadas desde el comienzo de la actividad.

Transcribo dos historias narradas por sendos pacientes del MA&TCh con el objeto de percibir el programa desde quienes lo reciben y practican. Estas historias tienen el valor de ser expresadas desde una perspectiva personal, ajena a la ciencia y al conocimiento teórico de su ejercicio. Quitaré los nombres,[8] pero mantendré la narrativa de sus experiencias personales hasta donde la traducción lo permita.

Uno de ellos tiene 36 años y desde hace 10 años ha estado bebiendo diariamente. A pesar de ello pudo mantener su trabajo, pagar sus cuentas, etc., pero su adicción estaba afectando seriamente a su vida. “Creí que no había ninguna esperanza y que mi vida no podría prosperar más que hasta aquí. Estaba trabado pensando que así sería hasta el final de mi vida.” Su familia y amigos le ayudaron a que reconociera su adicción y aceptó ingresar en el programa largo de la escuela. Esto fue hace 10 meses.

El otro tiene 30 años y sufre su adicción desde hace 16 años. Comenzó utilizando marihuana y alcohol a la edad de 13 años y cuando llegó a los 18 comenzó a ingerir metanfetaminas. Estuvo preso en varias ocasiones e intentó diversos tratamientos sin éxito. Su gran disparador fue su hijo de 2 años y medio que no pudo ver crecer por haber estado preso. En 2011 fue liberado pero continuó con la metanfetamina endovenosa que lo llevó casi hasta la muerte por infección. Tres años más tarde conoció la escuela y cuando salió nuevamente de prisión se dirigió a ella. “Pasé por muchos cambios aquí. Vine rechazando la autoridad, no queriendo escuchar sobre reglas. Era horrible. Quería luchar todo el tiempo. Finalmente llegué a la conclusión de que si no cooperaba sería echado del instituto.”

La experiencia coral es narrada por ambos de forma similar. “Cuando firmé mi ingreso a la escuela sabía sobre el coro y que yo debería ser parte de él. Mi primer concierto fue sólo dos días después de ingresar en el programa y no sabía ninguna de las letras que debería cantar. Sin embargo, tuve que vestirme con el uniforme del coro, subir al escenario y básicamente tratar de sincronizar mis labios durante las canciones. Con el tiempo las fui aprendiendo, perdiendo el nerviosismo de los primeros días, disfrutando de los Spirituals, Gospels, y recibiendo el afecto de mi comunidad. Estamos llegando a nuestra gente con las canciones que cantamos. Si esto puede ayudar a otros, vale la pena.” Hoy, uno de ellos es uno de los directores de los once coros que tiene el instituto y responsable del sonido. “Cuando nos referimos a nosotros mismos decimos que somos una Banda de Hermanos por el tiempo que pasamos juntos. Nos ayudamos y nos desafiamos mutuamente. Y cuando tenemos éxito nos abrazamos y felicitamos. Es muy hermoso. El sentido de hermandad que se desarrolla es probablemente lo más encomiable del programa. El personal es bueno y las clases están bien, pero es la pertenencia lo que salvó mi vida.”

El canto coral es un salvavidas. Es un derecho humano del niño y una obligación de la sociedad hacer uso de él.

Revisado por Carmen Torrijos, España

[1] Vicente Garrido Genovés, Universidad de Valencia, España

[2] Marco Iacobini, “Las neuronas espejo”, Katz Editores, Madrid 2009

[3] Moya-Albiol, Luis; Herrero, Neus; Bernal, M. Consuelo, “Bases neuronales de la empatía”, Revista de Neurología; No. 50, pgs 89-100

[4] Decety, J., Ben-Ami Bartal, I., Uzefovsky, F., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2016). Empathy as a driver of prosocial behavior: Highly conserved neurobehavioral mechanisms across species. Proceedings of the Royal Society London – Biology, 371, 20150077.

[5] Mary Alice y Gary Stollak, Choral Journal, Choral activity, a team or a family?

[6] The Globe Theatre (el Teatro del Globo) situado en el barrio de Bankside sobre el río Támesis de Londres es la copia exacta del teatro donde Shakespeare ofrecía sus obras; Sir Laurence Olivier fue considerado el más grande actor del Siglo XX y era un especialista en W. Shakespeare y la Royal National Theatre Company fue la compañía de teatro que dirigió Sir Laurence.

[7] Maud Hickey http://www.huffingtonpost.com/author/maud-hickey

[8] Los nombres figuran en un artículo escrito por Pippi Mayfield en el DL-Online el 9 de setiembre de 2015.