Spotlight on Scotland

Graham Lack, composer and ICB Consultant Editor

As far as I know, the ICB has not yet focussed on the music of Scotland. There is a wealth of music to be discovered and I hope this brief spotlight on the country will prove useful to choral directors wishing to programme works from ‘North of the Border’, as we English are wont to put it. We are grateful to Alan Tavener, Katy Cooper and Meg Monteith for such helpful contributions and general information. Thanks also go to Christopher Glasgow at the Scottish Music Centre for his generous help, advice and contacts.

The first article looks at Robert Carver, a Scottish monk working at Scone Abbey in the early sixteenth century. His motets and masses represent a rare link to the repertoire of the Eton Choir Book, that spectacular repository of early Renaissance English music. Carver’s O bone Jesu, written around 1546, is in no fewer than nineteen voice-parts, evidence then, of an extraordinary virtuosic style, even if many works in possibly a recusant tradition would seem no longer to be extant.

For complex historical reasons and problems with music reception, there is little good music that the British Isles have to offer in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The centre of music-making had certainly long since moved to continental Europe. There is, then, a dearth of valuable choral works by Scottish composers, the same holding true for Wales, England – the exception being Henry Purcell (1659-1695) – and the Emerald Isle.

Thus, in the second article, arrangements for choir of Scottish folk songs are examined. For much of the twentieth century such pieces proved popular with many choirs the length and breadth of Britain. Two prominent figures who worked in the field were Hugh S. Roberton and Cedric Thorpe Davie.

The issue of choral music and the avant-garde did not go unnoticed in post-war Scotland, and mention must be made of Peter Maxwell Davies, one of the founders of the Manchester New Music Group, and whose St Magnus Festival on the island of Orkney has been going strong since the late 1970s.

Finally, the third contribution looks at the choral music of the contemporary Scottish composer Judith Weir. By now a truly established figure, she has added many valuable works to the a cappella repertoire (Two Human Hymns for chorus and organ should be singled out here), and composed a number of choral works with instruments. Her major works remain perhaps operatic, including A Night at the Chinese Opera and more recently Miss Fortune.

Robert Carver: Scotland’s Master of Polyphony

Alan Tavener, conductor and organist

The small but tantalising repertoire of Scottish renaissance music that survived the Reformation is headed by the exuberant and decorated music of Robert Carver in late medieval style. Little is known about the man himself, and the inscriptions on the surviving authenticated manuscript of his music caused more debate than conclusion on the part of musicologists Kenneth Elliott (whose work on Carver’s music dates back to the 1950s) and subsequently, in the 1980s, Isobel Woods Preece. More recently, D. James Ross has located Carver’s name, complete with the title ‘Canon of Scone’, in the Aberdeen Council Records of 1505 in the context of his maternal uncle Sir Andrew Gray (who, in 1484, had been identified in the Records as chaplain of St Nicholas Church, and is subsequently recorded as granting money for the celebration of a Mass of the Name of Jesus), and makes a persuasive case for Carver’s birth and musical education occurring in that city. Taken together, and coupled with Roger Bowers’ observations regarding old style and new style dating, we can be reasonably confident that Carver’s dates were 1487/8–ca.1568.

Under the Stewart Kings, the upper echelons of Scottish society enjoyed a true and richly supported cultural renaissance during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, despite it being an era chequered by military catastrophes at the hands of the English. James IV continued to lavish resources on their Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle, and contemporary accounts record that the Chapel boasted a virtuoso choral group and three organs, as well as a magnificent music library which, in 1505, included four choirbooks with gilt lettering. But not one of the music books or manuscripts survived the sacking of the Chapel Royal in 1559 by Protestant mobs and the ensuing decades of neglect brought about by the banning of the celebration of the Mass. It was against this background that Carver lived and worked.

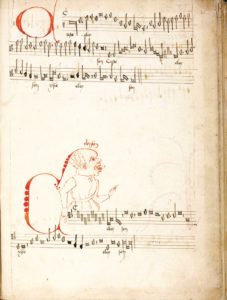

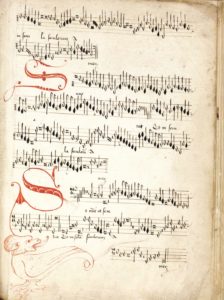

We are fortunate, however, that one choirbook, probably added to the library shortly after the 1505 inventory was taken, miraculously escaped – almost unscathed – the clutches of the anti-catholic fanatics, surviving the neglect of subsequent centuries and, remarkably, ‘turning up’ in the Advocates’ Library in Edinburgh. It contains the complete known authenticated works of Carver, self-styled as ‘Canon of Scone’ (the Augustinian Abbey some 30 miles north-east of Stirling), although the elaborate quality of the music suggests that he was writing for the Chapel Royal, where he possibly even took extended periods of leave. Originally known as the Scone Antiphonary, it is now housed at the National Library of Scotland Edinburgh as The Carver Choirbook in acknowledgement of the composer who provided most of its contents: five settings of the Mass and two motets therein are signed by Carver, and a Mass setting for three treble voices may also be attributed to him. As well as containing unattributed Masses, Magnificats and motets, there is music by the Franco-Flemish master Guillaume Dufay (supporting the view that Carver might have studied in the Low Countries) and motets that can be attributed to William Cornysh and Robert Fayrfax (on account of their presence also in the roughly contemporary Eton Choirbook, the rich source of English late Medieval and early Renaissance polyphony) which probably appeared in Scotland when James IV cemented the 1502 Treaty of Perpetual Peace with England by marrying Margaret Tudor, sister of the future Henry VIII. An additional attributed Mass setting for six voices may be found alongside material from England, France and the Low Countries in the Douglas-Fisher Partbooks in Edinburgh University Library

The earliest of Carver’s works, the Mass setting Dum sacrum Mysterium, has conflicting dates of composition (1506/1508/1511/1513), perhaps referring to a date of inception and dates of subsequent performances. Scored for ten voices (in modern terms SSAATTBarBarBB) in common with three of the other Mass settings it is a cantus firmus composition, the pre-existing melody being the Magnificat antiphon for the Feast of St Michael the Archangel. This chant is laid out by Carver in long notes, leading to a very slow rate of chordal change, and also causing adjacent chords to occur in regular and equal alternation, a possible debt to the very same phenomenon surviving in much Scottish folk music in the form of a so-called ‘double tonic’. Overall, the Mass setting is conceived according to the well-established practice of alternating sections freed from the cantus firmus for small groups of voices with sections for the full choir constructed upon the cantus firmus. Isobel Woods Preece has pointed to the possibility that large-scale vocal improvisation in as many as ten voices at once may have been standard practice in Scotland: it is certainly an appealing explanation for Carver’s penchant for music in many parts (one of the two motets being scored for nineteen voices), and it would also explain Carver’s remarkable tolerance of passing dissonance. The latest date assigned to this setting of the Mass might have been due to it being re-used for the coronation of the infant King James V, taking place at short notice (in the wake of the catastrophic defeat of his father at the Battle of Flodden) on 29 September 1513, the Feast of St Michael the Archangel (the Royal House of Scotland was dedicated to St Michael as its patron saint): the sumptuous nature of the Mass setting together with aptness of the cantus firmus do enhance the plausibility of this line of thinking.

Carver was already writing in a mature style and this hints at important, unknown influences. Whilst it is evident (if nothing else, from the contents of The Carver Choirbook) that he was in touch with contemporary musical developments in England and mainland Europe, we can only speculate about the local legacy of his music: on the one hand on the strength of his own work and, on the other hand, of any surviving music that pre-dates it. But we have only scant evidence of what Scottish tradition of church music Carver was born into: a thirteenth century MS of two-part polyphony associated with the Cathedral of St Andrews has survived (catalogued as Wolfenbüttel 2), distinguished by extraordinary virtuosity, vast vocal ranges and considerable demands on vocal flexibility: possibly an attempt to reconcile the latest French compositional techniques as exemplified by Leonin and Perotin with a native strand of highly embellished vocal improvisation. It offers a possible clue to the decorative character of Carver’s music some three centuries later, as does the improvised music of the Celtic minstrels who are recorded as attending the Scottish court under the patronage of James IV, who himself played the Celtic harp, or clarsach, (in contrast to his son James V who, like most of his European royal contemporaries, played the lute). This is particularly significant in the light of subsequent events, which not only had the effect of destroying the written musical legacy but, soon in its wake, also the practical musical legacy.

What is distinctive about Carver’s music? Opinions are widely contrasted, ranging from those anxious to identify a native Scottish style to those viewing it as essentially European. I detect similarities of decorative detail particularly with Antoine Brumel’s work, whilst Carver appears to be embracing the smooth imitative technique of Josquin des Pres in his Mass setting for five voices, a later work. The high treble writing so distinctive of the Eton Choirbook repertoire is evident in Carver’s earlier, larger-scale pieces, whilst elsewhere the treble line is of relatively modest scope. The extended treatment of the words ‘in nomine Domine’ (in the name of the Lord) in the Benedictus movements of his Mass settings is distinctive and could reflect an affection for his uncle’s devotion to the Name of Jesus, which is surely borne out by the vast 19-voice ‘pillars’ resounding to ‘Jesu’ throughout the motet O bone Jesu.

And what of Carver’s music today? It was originally intended for a highly skilled professional choir, and it is a credit to competent chamber choirs specialising in early music that they have been able to surmount many of the challenges of the music. However, there is no escaping that the reduced textures are complex and intricate, suggesting soloistic treatment requiring not only the intense musicianship of instrumentalists but also a cast-iron vocal technique. Examples of inspiration to today’s artists include James MacMillan’s 3-movement Tenebrae Responsories with its clear debt to Carver’s virtuoso style (a possible tribute to Cappella Nova, its commissioner), whilst Ronald Stevenson has set to music for 12-part choir James Reid-Baxter’s poem In Memoriam Robert Carver.

The textbooks have tended to focus on Robert Carver as the only known British composer to adopt the mediaeval French crusader song L’Homme arme as the cantus firmus for a Mass setting. Undoubtedly inspired by Dufay’s treatment of this melody, which was copied into The Carver Choirbook around 1506, it is a tribute to the international outlook enjoyed by Scotland at this time. As an exercise in musical technique, it is Carver’s most assured, and we find the cantus firmus cast in triple-time with the other duple-time voices; in duple-time with but a half-pulse ahead of the other duple-time voices; in a triple-time cross-rhythm with the other duple-time voices; and finally turned into another triple-time cross-rhythm against the other voices. This staggering example of technical, compositional prowess can only leave us wondering what else Carver the composer achieved – a question that we can always hope might be answered one day by the rediscovery of more of his work.

Carver’s music is published by Musica Scotica (Volume I: ‘The Complete Works of Robert Carver & Two Anonymous Masses’ edited by Kenneth Elliott, ISBN 0 9528212 0 6), and has been recorded by Cappella Nova: www.cappella-nova.com.

Alan Tavener is co-founder and Conductor of the Scottish-based professional vocal ensemble Cappella Nova, which performs internationally and has made 12 CD recordings. He has specialised in conducting the work of Robert Carver, as well as over 60 world premieres of choral works, ranging from three-minute a cappella items to major works, including John Tavener’s Resurrection with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, subsequently broadcast on BBC Radio 3, and James MacMillan’s Seven Last Words from the Cross with the BT Scottish Ensemble, broadcast as of seven films on BBC2. Recent projects have included a Masterclass for Student Choral Directors at the Moscow Conservatoire, and the presentation of Sessions at the 2010 Convention of the Association of British Choral Directors as well as a Paper Health and Wellbeing through Song at the 2011 Making Music Conference. Glasgow-based since 1980, he is also Organist and Choirmaster of Jordanhill Parish Church and Conductor of Strathclyde University Chamber Choir (for which James MacMillan composed 11 of his 14 Strathclyde Motets).

Alan Tavener is co-founder and Conductor of the Scottish-based professional vocal ensemble Cappella Nova, which performs internationally and has made 12 CD recordings. He has specialised in conducting the work of Robert Carver, as well as over 60 world premieres of choral works, ranging from three-minute a cappella items to major works, including John Tavener’s Resurrection with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, subsequently broadcast on BBC Radio 3, and James MacMillan’s Seven Last Words from the Cross with the BT Scottish Ensemble, broadcast as of seven films on BBC2. Recent projects have included a Masterclass for Student Choral Directors at the Moscow Conservatoire, and the presentation of Sessions at the 2010 Convention of the Association of British Choral Directors as well as a Paper Health and Wellbeing through Song at the 2011 Making Music Conference. Glasgow-based since 1980, he is also Organist and Choirmaster of Jordanhill Parish Church and Conductor of Strathclyde University Chamber Choir (for which James MacMillan composed 11 of his 14 Strathclyde Motets).

Email: alan.cappella-nova@strath.ac.uk

The Use of Folksong in Scottish Choral Music

Katy Cooper, conductor, arranger and musicologist

Scottish traditional music has long attracted interest from around the world. In this article I hope to highlight some of the arrangements and folksong-influenced works by Scottish, or Scotland-based composers beginning with the early enthusiasts of the first folk revival.

Folk music in Britain is said to be going through something of a revival at present. Folk-influenced bands and artists like Mumford and Sons regularly feature in the charts and the establishment of undergraduate courses in traditional music is giving musicians in the UK the chance to focus on the genre at this level. The popularity of choral arrangements of folksongs was cemented in an earlier folk-revival, when composers like Vaughan Williams not only arranged songs (including music from Scotland), but also collected material as active members of the Folk Song Society (founded in 1898).

In his 1948 article for the journal of what eventually became known as the English Folk Dance and Song Society, Frederick Keel points out that this organisation initially “resisted all attempts to narrow its field or to apply the name ‘English’ or ‘British’.” Rather, it was founded as “a Folk Song Society situated in England, not one confined to the preservation of English Folk Song.” In fact, Sir Alexander MacKenzie, a prominent and influential Scottish composer, was one of the first members of the organisation. MacKenzie produced several collections of traditional Scottish songs arranged for piano, but his works for choir do not apparently include Scottish song settings. Similarly the choral works of Hamish MacCunn, famous for his evocative Land of the Mountain and the Flood, include Four Scottish Traditional Border Ballads for choir and orchestra, but few smaller scale arrangements. Much Scottish choral music of this period is now out of print and little known by modern choirs, but libraries and archives such as the Scottish Music Centre, as well as several online repositories are well worth exploring.

Mackenzie was not the only Scottish musician involved with the work of the Folk Song Society. In subsequent decades, Scottish enthusiasts George Barnet Gardiner and Francis Collinson collected traditional material in Scotland and England. Francis Collinson, later the first musical research fellow at the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh, made many arrangements of Scottish songs including settings of The Flowers of the Forest, Bonny Dundee and The Bonnie Lass of Albany. A few of these were published but many of them remain in autograph manuscript only.

Collinson also collected and made choral arrangements of Gaelic songs, reflecting the rise in popularity of Gaelic choirs, which were to be found all over Scotland by the 1930s. The first of these was Glasgow’s St Columba Choir, founded in 1874. The movement was encouraged by the foundation (in 1891) and on-going popularity of the ‘National Mod’, modelled on the chorally-rich Eistedfodd in Wales. The subsequent century has produced a rich and varied repertoire of Gaelic choral music, little known outside of Gaelic choirs. Links to resources including sheet music can be found on the website Comunn nan Còisirean Gàidhlig (Gaelic Choirs’ Association: www.gaelicchoirs.org.uk).

The early twentieth century not only saw success for Gaelic choirs – the world famous Glasgow Orpheus Choir under the leadership of its founder Hugh S. Roberton introduced millions of people throughout the world to Scottish folk song, many such songs (or indeed most) arranged by Roberton himself. International touring and recording played an important role too. Roberton also wrote the texts to such famous songs as Westering Home and the English version of Mhairi’s Wedding, based on the original Gaelic. The stylised and (now) nostalgic sound of the choir, together with the simple, declamatory arrangements of Roberton are eminently singable, and evocative of their time.

Folksong arrangements continued to be a popular choice for choirs throughout the twentieth century, with composers producing both settings of songs, and new compositions based, or influenced by traditional material. Cedric Thorpe Davie’s ‘cheerful tonality’ produced many popular arrangements including competition pieces for the National Mod, and larger scale choral works incorporating folksong. The next generation of Scotland-based composers, including Ronald Stevenson, Thomas Wilson and later Peter Maxwell Davies were all heavily influenced by Scottish material and produced – and continue to produce – some exceptional choral pieces, albeit relatively few that are simply arrangements. Stevenson’s choral music, for example, includes a motet in memory of Scottish Renaissance composer Robert Carver, the angular A Medieval Scottish Triptych and the folksong-inspired, large-scale piece for orchestra and chorus In praise of Ben Dorain.

Just as the choirs of the past prompted many choral arrangements, so today Scotland’s choirs and choral organisations continue to commission and produce new settings, perhaps the most prominent example being the publishing wing of the National Youth Choirs of Scotland. Their publications for young singers, include the SingSilver and SingGold volumes featuring arrangements and new choral works by composers including Sally Beamish, William Sweeney, Eddie McGuire, John Maxwell Geddes and Ken Johnston. Johnston’s close association with NYCOS has also produced popular arrangements including spirited versions of Roberton’s Westering Home and Air Falalalo.

Possibly the most prominent Scottish composer writing for choir today is James MacMillan, whose distinctive choral style is suffused with influences from his Scottish heritage. This influence is seen in So Deep, an unusual setting of Robert Burns’ My Love is like a red, red rose, and The Gallant Weaver.

As a folk music enthusiast, and a choral singer, I find myself drawn to two worlds. Harmony singing, unordered and spontaneous, is my favourite characteristic of traditional singing sessions in Scotland and the rest of the UK, and many community choirs incorporate some of this material into their repertoires. I believe there is also a place for the choral arrangements of the early twentieth century offering thoughtful settings of words as well as MacMillan’s more recent re-imaginings of Burns. This really builds on the folk material, using the choir in an imaginative way to support the melody lines. For me, the practice of arranging folksong for choir is a tradition in its own right, one with a rich history and, considering the current revival, with a fascinating future too.

Katy Cooper is a choral conductor, arranger, tutor and musicologist. She has lectured at the Universities of Aberdeen, Strathclyde and Glasgow, where she is completing her PhD, and trained as a choral conductor with Sing for Pleasure and is now conducting tutor and editor of their national newsletter. She conducts Glasgow Madrigirls (madrigirls.org.uk), Cathures (cathures.org.uk), Happy Voices (a children’s choir), and workplace- based choirs at Glasgow Life and John Lewis (Edinburgh), and sings with Sine Nomine International Touring Choir, Glasgow University Chapel Choir, Sang Scule (sangscule.org.uk), and folk-harmony groups Muldoon’s Picnic (muldoonspicnic.org.uk) and The Crying Lion. A collation of her arrangements for choir was published by Sing for Pleasure in 2011. Email: katylaviniacooper@googlemail.com

Intimacy at Some Remove:

The Choral Music of Judith Weir

Graham Lack, composer and ICB Consultant Editor

The music of Judith Weir inhabits a strange world. Her style is an intimate one, but somehow remains unfamiliar even when listeners feel they have got to know and understand it. Her choral works offer some striking textures and result in quite gratifying sounds, ones tempered by more than a measure of restraint. But whatever she writes, the music serves the emotional content of the text she sets.

The use of the organ in Ascending into Heaven reveals the influence of her teacher, Olivier Messiaen. It was completed in 1983 and sets a Latin text by Hildebert of Lavardin (1056-1133). The role of the organ itself is an unexpected one – in all of her music she remains ready to spring a surprise – and resembles that of an orchestra more than anything else. Certainly, it does much more than provide a commentary, and Weir does not use it merely to join one section of the work to the next. Choirs will welcome the directness of the choral writing, which is affirmatively modern but remains most accessible.

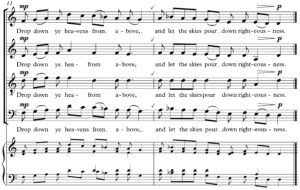

Her Drop down ye heavens was written for the Chapel Choir of Trinity College Cambridge, and premiered in 1983. She sets words from the Advent Prose and proffers a perfect jewel-like hymn. This is Weir at her most elegiac.

Judith Weir: ‘Drop down ye heavens’, bars 11-end

(Click on the image to download the full score)

Another Cambridge commission was Illuminare, Jerusalem, commissioned by the renowned Choir of King’s College, which gave the first performance back in 1985 at the famous service of Nine Lessons and Carols. The text is in Gallic, and Weir achieves some dense harmonic moments amidst the lively rhythms.

Perhaps her most attractive and, in the best sense of the word, popular choral works to date are the Two Human Hymns, a commission from the University of Aberdeen for its Quincentenary in 1995.Weir sets words by George Herbert, as well as another seventeenth century poet, Henry King. The choral writing is at its most lyrical, in stark contrast to an organ part that constantly interrupts harmonic progress. The result is a remarkable sense of tension. The organ episodes in the second setting are overt toccatas. The first setting of the pair, ‘Love Bade Me Welcome’, the composer arranged two years later for a cappella forces.

Judith Weir: ‘Love bade me welcome’ (a cappella version), bars 1-14

(Click on the image to download the full score)

As for My Guardian Angel, commissioned in 1997 by the Spitalfields Festival, this would seem to be a fairly direct sing. But with Judith Weir, simplicity hides quite subtle complexities. And any choir attempting the piece will surely notice the depth of the harmonic thinking as one rehearsal follows another.

Vertue was also written for London’s Spitalfields Festival, receiving its premiere there in 2005. The composer sets three poems by George Herbert, demonstrating a compositional response that is quite severe in its directness and the use of a harmonically bare musical language. Here, Weir is at her most thoughtful, and an engaged audience will hear her musical voice distinctly.

Her setting of Psalm 148 was to a 2009 commission for the 800th anniversary of the University of Cambridge. The work’s forces are somewhat unusual: choir and trombone. She does not, however, merely allot a bass line to the instrument, but forces it to add some sturdy counterpoint to the choir. Somehow she manages to produce a setting that is overtly hymnic yet oddly introverted. The sounds are spare, and part of a detached sound world lost in its own reverie. With but an occasional nod to the sentimentality of the text, Weir charts a course through dangerous harmonic waters, allowing the motivic work at the composition’s surface to take the listener from one tonality to the next.

A poet whom Weir obviously finds intriguing is e.e. cummings, and her setting of his little tree, from 2003, matches the words perfectly. Cast as three short independent pictures, the piece is for choir and marimba. It was a commission by the Young People’s Chorus of New York. Against the three-part upper voices the marimba acts like a continuo, expanding the musical texture. As with cummings, what you see is not necessarily what you get, or in the case of Weir, what you hear…

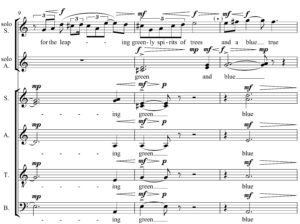

In a second cummings setting, also completed in 2003, a blue true dream of sky, we have quite a rapturous work, one which makes us turn instantly to Weir’s preoccupation with the mystic Hildegard von Bingen. The piece was written to a commission by choral director and organist Philip Brunelle, the premiere being given by his Plymouth Church Choir in Minneapolis. The prominent solo soprano part was written for Maria Jette. Two alto solos occupy the musical background and allow the solo line, the chorus, and their own music gradually to align themselves.

Judith Weir: ‘a blue true dream of sky’, bars 9-11

(Click on the image to download the full score)

Judith Weir’s music is published by Chester-Novello, part of Music Sales Group, and we hope this brief survey will have sparked an interest amongst choral directors.

Judith Weir has interests in narrative, folklore and theatre, and these have found expression in a broad range of musical invention. She is the composer and librettist of several widely performed operas whose diverse sources include Icelandic sagas, Chinese Yuan Dynasty drama and German Romanticism. Folk music from the British Isles and beyond has influenced an extensive series of string and piano compositions. For many years she has worked in England and India with storyteller Vayu Naidu, and on film and music collaborations with director Margaret Williams. She spent some time as resident composer with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and has also composed for the Boston Symphony, BBC Symphony and Minnesota Orchestras.