Working With Male Adolescent Voices In The Choral Rehearsal: A Survey Of Research-Based Strategies

Over the past century, a significant amount of research focusing on the vocal development of adolescents has been contributed to the field of music education. Researchers have attempted to uncover the various stages of vocal development in both adolescent males and females; the results of these studies have served as foundational material for the teaching philosophies and methodologies that are used in general and choral music classrooms today. Although the research has shown that both adolescent males and females experience some type of vocal change, there is comparatively more literature devoted to the vocal development of young men. In addition to addressing the vocal needs of adolescent males, it is also quite possible that the emotional, psychological and developmental needs of these young men must be addressed if they are to be successful in rehearsals and remain in a singing program throughout their secondary school years.

The body of scholarship specifically focusing on adolescent male voices at the secondary level has provided a framework for teachers to develop teaching techniques for the rehearsal. The pedagogical strategies that have been compiled from and supported by this study have been organized into the following categories:

- understanding the changing voice;

- assessing the voice;

- placement of the male adolescent singer;

- explaining voice change;

- classifying and labeling the adolescent boy’s voice;

- guiding general vocal production and development;

- developing vocalises and warm-ups for the rehearsal;

- adjusting pitches and vocal lines in the choral score;

- incorporating analogy and movement into the rehearsal;

- maintaining a healthy and productive rehearsal environment.

Using the above categories as an organizational guide, the objective of this study is to offer research-based strategies and best practices that will assist the choral director in rehearsing male adolescent voices at the middle and high school levels.

Understanding the Changing Voice

When preparing to teach choral music at the secondary level, the conductor must be equipped to help these singers manage their developing voices. Therefore, one of the first steps toward successfully working with adolescents in a choral rehearsal is for the teacher to obtain a thorough understanding of the changing voice.1 With respect to male adolescents, Henry Leck states that the teacher must “understand vocal production for the boy’s changing voice, what voice part to have them sing, and how to avoid problems and vocal strain.”2 Not only should the choral teacher be aware of the physical changes associated with adolescent male vocal development, but he or she should also understand the emotional dimensions associated with vocal change. Even though every adolescent boy’s physical and emotional development path will be unique, having knowledge of typical male adolescent behaviors may enable the choral director to plan and facilitate effective rehearsals.

Assessing the Voice

In order to adequately plan rehearsals and set goals for the choral program, it will be necessary to test each individual voice. Given that boys at the middle and high school levels are often self-conscious about their bodies during adolescence, it is important for the choral director to be sensitive and creative when attempting to assess these voices. Even the type of terminology used for the assessment process can affect the comfort level of the singer and in turn impact the overall recruitment effort. David Friddle, for example, offers the term “voice check” as a way of alleviating the anxiety that is often associated with the term “audition.”3

An accurate assessment of the each boy’s voice is absolutely necessary so that he can be placed in the proper section and provided with musical challenges that fit his current vocal abilities. Veteran choral pedagogue Michael Kemp amplifies this point:

“For boys whose voices are about to change or are in the midst of change, you must always be aware of what pitches they can actually sing. This requires checking their high and low notes every couple of weeks, and making sure the notes you are asking them to sing are possible notes for them.”4

This author advocates a “row-by-row” assessment process within the context of the rehearsal. In this way, the choral director can frequently check for boys who are experiencing vocal difficulties and offer assistance (or a follow-up “voice check”) in a timely fashion.

Proper assessment of the adolescent male singing voice begins with locating the approximate pitch of the boy’s speaking voice, which was found to be approximately 2 to 3 semitones above the lowest note in the singing range5. Terry Barham and Darolyne Nelson suggest having the boy say “hello” to you, followed by leading the boy from his speaking pitch (as scale degree 1) on “hello-o-o-o-o” using scale degrees do-do-re-mi-re-do6. As with most vocal exercises during the initial assessment process, it is important to guide the singer slowly and carefully, listening for any signs of vocal strain with each modulation. Using vocalises that employ a small range, such as a third, make it possible for boys with limited singing ranges to be successful.

In the spirit of Barham and Nelson’s research, the author has developed the following exercise (to be performed and modulated in whatever keys necessary) to initially assess the boy’s singing range. Only utilizing the range of a third and written in a jazz style, the vocalise consists of whole-steps and half-steps (ascending and descending):

Figure 1. Rollo Dilworth, Jazz-Style Warm-up © 2012 by Hal Leonard Corporation. Reprinted by permission.

A common pattern used to test voices consists of a descending “so to do” pattern in a range that is comfortable for the singer. Consistent with the research, this kind of warm-up allows the singer to gradually ease from the higher to the lower registers of the voice, all within the range of a fifth. When singing this type of exercise, Jonathan Reed recommends using a resonant vowel (such as “ee”) and a percussive consonant (such as “b”).7

Apart from using composed vocalises, it is also reasonable to ask the adolescent boy to sing a song with which he is familiar. In a more recent qualitative study, Barham notes: “for several teachers, discovering a boy’s speaking voice pitch level is a prelude to singing a familiar song in the corresponding key.8 A short list of popular tunes recommended by expert in the field include Jingle Bells9, Rock Around the Clock10, My Country, ‘Tis of Thee11 and We Will Rock You!.12

Beyond the task of documenting the singer’s vocal range on a note card or audition form, Barham and Nelson, Conrad, and Freer all suggest posting changes in the singers’ vocal range in the classroom on a wall chart or bulletin board.13 By placing the progression of each boy’s vocal range on display, it is hoped that students will build camaraderie and develop a deeper understanding of how the voice change process varies among individuals.

Classifying and Labeling the Adolescent Boy’s Voice

Properly assessing the adolescent boy’s voice will allow the choral director to determine his particular stage of vocal development and thus enable him to be placed on the proper vocal part in the rehearsal. Over the years, several research-based models documenting the various stages of voice change for adolescent boys have been developed. These models present three,14 four,15 and as many as six16 categories of vocal development for adolescent boys. Although the fine details concerning each model are beyond the scope of this particular study, it important to note the terminology used to describe the various vocal stages. Some of these models use the labels “soprano,” “alto,” “alto-tenor,” “unchanged” and “mid-voice” for voices that are either in pre-transitional or transitional stages. Labels for voice changes that are more settled include “tenor,” “new baritone,” “settling baritone,” “bass-baritone,” and “bass.” Barham’s survey of over 40 “master teachers” of choral music at the middle level revealed that 86% of them use the terms “tenor,” “baritone,” or “bass” while 60% use the term “unchanged voice.”17 Only 38% of the surveyed choral directors use the term “soprano or alto” and 21% of them use the terms “treble” or “cambiata.”18 Even though the number of teachers surveyed for this study was relatively low, the results may provide guidance for today’s choral director when considering terms for labeling adolescent boys. Paul Roe believes that “the young man does not want a feminine name attached to his voice.”19 In agreement with Roe, and based upon years of working with adolescent male voices, Leck asserts that “a boy does not want to be called a soprano or alto.”20 This is not to imply, however, that all boys, with both unchanged and changing voices, should be lumped into a catch-all “baritone” part for the sake of organizational simplicity and maintaining morale. Leck offers the following testimonial as a warning against pigeonholing all middle school boys into the “baritone” category:

In one disastrous episode, a seventh grade choir teacher put a group of girls on one side and called them sopranos and another group of girls on the other side and called them altos. All twenty-five boys were called baritones and put in the center. This resulted in tone clusters because many boys were unable to sing the pitches. The boys took no pride in the sounds they were making and acted out with major discipline problems. Though it is perplexing to decide what part they should sing, it’s important not to pigeonhole singers.21

Friddle notes that “teenage boys have fragile egos; their masculine identities are only beginning to formulate; thus, it is important to find names that will allow them to feel comfortable in their newly assigned section.”22 It should be noted here that some choral directors use numbers (such as Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV) to label voice parts rather than the tradition terms “soprano,” “alto,” “tenor,” and “bass.” With the respect to psychological and emotional development, Barham makes the following point: “What boys are labeled, musically, is not as important as your continually nurturing their self-esteem and helping them recognize their overall growth, personally and musically, during the year.”23

Placement of the Male Adolescent Singer

Discussions of whether the adolescent male singer should be placed in a single-gender or a mixed-gender rehearsal setting are ongoing. Even within a mixed-gender rehearsal setting, researchers have varying ideas about exactly where adolescent boys should be seated. Stage of vocal development is a major factor affecting seating preferences in both single-gender and mixed-gender rehearsal settings.

In a 1960’s article, Robert Conrad stood strongly in favor of the mixed gender setting, offering the following rationale: “to further stimulate the interest of boys and girls in singing, it is best to work with mixed group rather than boy’s and girl’s glee clubs.”24 Beyond the philosophical preference for mixed-gender rehearsals, there can be scheduling issues that prevent boys and girls from having separate rehearsal periods during the school day.

In more recent years of literature and debate on the subject, numerous researchers and pedagogues have espoused favorable opinions regarding single-gender rehearsals at the middle school level. Advocates for the all-male rehearsal configuration offer several advantages:

- “social problems are almost eliminated because junior-high boys and girls work much better when there are no members of the opposite sex around;”25

- “this arrangement makes it possible to address with the guys topics such as changing voice, falsetto singing, and increasing he range, in a non-threatening environment;”26

- “it is less embarrassing to the one with the unmanageable voice to have only men in the class;”27

- “in an all-male setting, young men are less self-conscious and, thus, more easily persuaded to sing;”28

- “…an adolescent male chorus is another means by which to keep interest in singing strong among pubertal boys. The esprit de corps that is established creates a bond beneficial to the entire music program.”29

In an experimental research study, Swanson found it helpful to place boys in the earlier stages of voice change in one class while placing boys who were in the latter stages of voice change in another.30 Over a nine-month period (September to May), the junior high boys who were a part of the experimental group demonstrated, on average, an acquisition of more pitches in their range, a higher level of overall musicianship, and a more positive attitude toward music in general.31

Given that it is not always possible to schedule single-gender rehearsals during the school day, choral directors might consider a separate “special” rehearsal for boys either before of after school. By organizing “special” rehearsals for adolescent male singers, this population can be afforded the opportunity to “be themselves” and sing in a safe, comfortable environment.

When considering the placement of singers in a mixed-gender rehearsal, Freer suggests positioning boys to one side rather than in the middle of the choir.32 On the opposite end of the seating debate, Don Collins believes that middle level/junior high boys need constant attention and therefore should be placed in the front and center of choir with the girls seated both behind and to the sides of them.33 Cooper and Kuersteiner assert that adolescent male singers (both baritones and cambiatas) should be placed in the front rows of the choir formation while the girls sit in the back rows,34 and boys who experience pitch and vocal production problems should sit between stronger singers.

Roe suggests that boys who still sing in the treble register should sit next to sopranos and altos while making sure they are on the edge of the section next to the tenors and basses.35 With respect to both Collins and Roe, the author suggests the following mixed-gender formation for adolescent voices:

A2 A1 S2 S1

T1 T2 B1 B2

The above seating formation serves at least three pedagogical purposes:

- tenors and altos can share pitches when necessary;

- boys with changing voices can easily shift between male voice parts; and

- boys are able to receive attention from the choral director by sitting in the front rows.

Whether the discussion is focused upon single- versus mixed-gender rehearsals, or the exact position of the male singer within the rehearsal formation itself, the placement of the adolescent male singer will not only impact the rehearsal process itself, but it will also have some affect on the young man’s musical (and perhaps emotional and psychological) development.

Explaining the Voice Change to Singers

For certain, it is important to explain and discuss the process of voice change to both male and female adolescent singers. According to Roe, “the teacher must discuss the physiology of the voice with each class.”36 Although researchers have varying opinions on how much information and detail should be presented, it is generally agreed that the choral director must find opportunities, both within and outside of the rehearsal context, to explain the concept of vocal change to both boys and girls in understandable terms. With respect to explaining the voice change process to boys, Frederick Swanson, while conducting experimental research in the 1960’s, offers the following:

“… Boys’ voices change, they get deeper, richer, stronger, and move into what we call the tenor and bass ranges. You are about to be given a new voice, maybe a more beautiful voice, and a whole new kind of singing will open up for you. But there is a price to pay, and all boys must pay it before they become men. For a while you will not be able to handle this new voice, and in some ways you may have to learn to sing all over again.37

While the above text reflects an earlier era in terms of language style, the crux of what Swanson has to say may assist the teacher in crafting a “speech” of his or her own using the “vernacular of the day.” However the choral director chooses to explain the voice change to singers, Freer notes that the director must be consistent in the terms he or she uses so that adolescents can successfully incorporate these new terms into their vocabulary.38

Guiding General Vocal Production and Development

Experts advise choral directors to exercise great care when working with adolescent male voices. Although specific approaches are varied and diverse, the following general principles can be gleaned from the research:

- enforce proper posture and breathing habits; 39

- use descending exercises to connect the head voice with the emerging chest voice;40

- guide the head voice through the passagio into the chest voice with a light head tone41

- make sure (through watching and listening) that the voice is not placed under any strain while singing42

- review and or re-learn vocal techniques used prior to the onset of voice change43

- provide appropriate vocal models from various walks of life who can successfully demonstrate proper vocal technique, including high and low range singing44

- allow the boys to sing where they are most comfortable45

- allow the boys to vocally rest when they experience fatigue46

Developing Vocalises and Warm-ups for the Rehearsal

With respect to vocal warm-ups for adolescent boys, there is a common theme among the research literature: allow the boy to access both the high and low ends of his vocal range during the rehearsal. Some researchers and choral conductors refer to the high end of the boy’s voices as the “upper range” or “high voice” while others employ the term “falsetto.” It should be noted here that although some choral pedagogues use the aforementioned terms synonymously, some researchers do not see the two terms as being one in the same. Phillips makes such a distinction, and notes that “the pure upper voice in the male changing and changed voice will sound much like the prepubertal boy’s voice in the octave from c2 to c3.”47 Phillips goes on to mention that the upper voice sound will be fuller and freer than a “falsetto” sound (a weak and unsupported tone characterized by a high larynx).48 Regardless of the terminology used, “it is important to vocalize throughout the range and to encourage the young men to sing as high or low as possible without forcing.”49 Roe summarizes his position as follows:

“The teacher must not succumb to the temptation of overworking the voice in the upper register, at the expense of the development of the lower voice. Many vocal instructors allow the students to use only the lower voice (boys will naturally want to sing with their lower voices only), but this procedure will cause almost as many problems as the high- voice procedure. The proper pedagogical procedure encourages development of the lower range, retention of the upper range, and development of the middle range until the two segments join together in on smooth, continuous range.”50

With the goal of full range exploration in mind (in conjunction with the concept of gently bringing the head voice down in the chest register), numerous pedagogues have developed vocal warm-ups for the adolescent male voice. Such examples include “so to do” descending exercises that begin somewhere between the A and C above middle C.

Through his research, Freer concludes that “the composite unison range of an adolescent vocal ensemble will be about a sixth, roughly from a G up to an E, with students singing in different octaves as appropriate.51 The implication here is that unison vocal warm-ups may not always be the most effective for adolescent singers if the goal is to explore the entire range. As an alternative to vocalises that are pitch-specific, Freer offers the following guidelines when constructing appropriate vocal warm-ups for adolescent singers: a.) develop vocalises that are not pitch specific; b.) derive vocalise material directly from the repertoire being prepared; and c.) construct improvisatory activities that teach vocal skills yet leave pitch choice to the students.52 An example is an exercise called “Scribble,”53 in which a randomly drawn wavy line (displaying “peaks” and “valleys”) is drawn on the board. Students are directed to sing neutral syllables as the choral director (or another student) traces portions of the scribbled line with a pointer. Using a warm-up activity like “Scribble” enables the students to comfortably explore their individual range without being locked into singing specific pitches.

Adjusting Pitches and Vocal Lines

Given that many male adolescents may experience multiple shifts in singing range during the period of vocal change, and, given that some choral repertoire may not take into account these shifts, it may be necessary for the choral director to make some adjustments to the written pitches. Barham offers five types of solutions: transposition, swap parts, octave displacement, doubling parts, and writing a new part.

Transposition. Choral directors need to be able to transpose vocal exercises and selected repertoire into keys that are most comfortable for the singers. Wiseman contends that “the teacher’s ear must be constantly on the alert and he must be prepared to transpose exercises and songs into any key which is suitable and comfortable.”54

Swap parts. Choristers are encouraged to shift to another vocal line, if necessary, in order to sing notes that fit their current vocal range capabilities. Sally Herman has developed a “voice pivoting approach” that serves as a cornerstone of her choral teaching philosophy:

“Another very important ingredient of successful music reading and rehearsing is to keep all students the best part of their voice ranges (tessituras) for most of the rehearsal. This is especially true for the male adolescent singer. In any vocal composition, number the singes in a given section according to voice range, and develop a worksheet to interchange the individual voices that are best suited to both the singer and the music. A baritone might sing second tenor for four measures and then pivot to baritone for three measures.”55

Octave displacement. A simple solution is to have the boys drop the octave when the part gets too high. Barham believes that this procedure can be used for treble clef and bass clef singers.56 Based upon experience, this author cautions against excessive use of octave displacement for baritones and basses. In general octave displacement may be necessary for these voice parts when the written pitches fall above or below the staff. Baritones and basses should be encouraged to find their new voices where pitches lay on the staff; otherwise, they will continue to sing below the staff (where it may be easier) at the expense of developing and securing the upper portions of their singing range.

Doubling parts. The strategy of having two voice parts sing in octaves can successfully accommodate changing voices. When using two-part literature, a common approach involves placing tenors on the soprano part at the octave while placing the baritones/basses on the alto part at the octave. Unchanged voices can remain in the octave that best fits their current vocal range. Barham notes that “octave doubling can combine with octave displacement occasionally moving back to the written pitch, thus creating a new part.”57 Rather than employing two-part literature in an SATB rehearsal setting, Jerry Blackstone encourages the use of literature that contains parts written explicitly written for tenors and basses because doubling parts at the octave can inadvertently make these male singers feel as though their role in the choir is a secondary one.58

Writing a new part. Occasionally the male adolescent voice may be limited to just a few pitches; therefore, it may be necessary for the choral director to create a new vocal line. Leck suggests that boys who are learning to use their new voices may need to sing a vocal line that is easy, such as the melody.59 Roe concurs with Leck, stating that “it may be necessary to write easy parts for problem voices”60 and, in such cases, “have only one voice part a time sing a melody it its range.”61Kemp summarizes the strategy of adjusting pitches for the adolescent singer by stating the following: “whatever you create for the changing boys to sing, try to use predominantly the pitches they can sing with the most confidence.”62

Incorporating Analogy and Movement into the Rehearsal

In recent years, there have been an increasing number of research studies on the concepts of analogy and/or movement in the choral rehearsal. However, few studies have offered analogies and/or movement strategies that specifically target the needs and interests of the adolescent boy. Both Frederick Swanson and Patrick Freer have discussed the use of sports analogies with adolescent boys in the choral rehearsal. With reference to the same experimental study cited earlier in this article, Swanson found that when “using the analogy of developing skills in sports, [the research team] sold the boys on the ideas that ‘setting up exercises’ would develop control and increase ability.” Therefore, Swanson and his team proceeded to use sports analogies when talking to the boys about their vocal technique. The following chart outlines the concepts Swanson and his team covered in rehearsal, along with the analogies that were presented verbally to the boys:63

|

VOCAL CONCEPT |

SPORTS ANALOGY (Verbalized) |

|

Breathing exercises |

“Any swimmer or runner needs good breathing habits to sustain him.” |

|

Relaxed, open throat |

“Any batter needs a relaxed swing.” |

|

Scales and arpeggios to increase range |

“Any golfer needs to increase his distance.” |

|

Vowel formation and focus of tone |

“Any basketball player has to improve his aim for the basket.” |

In his video entitled Success for Adolescent Singers, Freer challenges students to think of singing as an athletic experience in which all the muscles in their bodies must be used in a very healthy way.64 In a more recent research study, Freer discovers the following:

“The fact that there are strong similarities in the physical foundations of singing and weight lifting affords choral conductors a unique opportunity to reframe singing during the period of pubertal voice change as an athletic endeavor. To embrace this change requires choral conductors to reinforce what students already know from their experience in athletics and weight rooms with analogies and descriptions of parallel and related activities.”65

Freer presents a host of physical activities that will enable middle school boys to develop healthy relaxation, alignment (posture), breathing, and vocal production habits.

With respect to the research, the author offers the following sports-related technical exercises for adolescent boys:

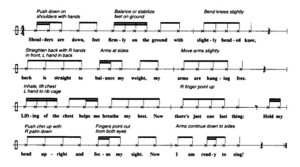

Posture Perfect! (A Rap)

Objective: To maintain good standing posture.

Directions: Chant the rap below, adding the suggested movement as desired.

Rollo Dilworth, Posture Perfect!, from Choir Builders © 2006 by Hal Leonard Corporation. Reprinted by permission.

Breathing with the Basketball

Objective: To promote controlled, diaphragmatic breathing.

Directions: While standing with good posture, pretend to bounce a basketball at waist level. While bouncing the imaginary ball, commence breathing pulsations in quarter note durations, making the sound “tss.” When it is time to “shoot the ball,” the singers should lift both arms to simulate the release of the ball and softly say the word “swish.” On cue from the teacher, and without missing a beat, students can perform “tss” 3 times and a “swish,” followed by “tss” 4 times and a “swish,” etc. until reaching “tss” for the ninth time followed by a final “swish.”

Bungee Cord

Objective: To access head voice.

Directions: Place the index and middle fingers of one hand in the palm of the other hand (to look like a person’s legs). The “person” should leap off of the bridge making a “siren” sound in high head voice. The vocal pitch should be sustained and change pitch according to the direction of the jumper. At some point, the bungee cord should snap the jumper back in an upward direction, back onto the platform (the palm of the other hand).

Playing Sports

Objective: To sing with energized and sustained breath support.

Directions: Choristers are encouraged to use movement to simulate the motion of a sports activity while singing the exercise (below) on neutral syllables. The teacher (or a designated leader) can determine the specific syllable and sports activity as the pattern modulates. Singers should be directed to simultaneously inhale and prep their hands for the sporting activity during the rests. Singers must simulate the designated sport while singing the pattern, ensuring that the motions and voices are sustained until the end of the pattern is reached. Sample sports activities include: throwing a football, swinging a bat, bowling a ball, throwing a Frisbee, and shooting a basketball.

Figure 3. Rollo Dilworth, Playing Sports © 2012 by Hal Leonard Corporation. Reprinted by permission.

Similar to Freer, Phillips believes that “by concentrating on the physical act of singing, students learn that singing requires the same preparation as do sports.”66 Although he did not single out adolescent boys in his discussion, Robert Shewan believes that physical calisthenics, when connected to musical concepts such as tempo and rhythm, can be successfully incorporated into a secondary choral rehearsal.67

Aside from and in addition to using sports analogy, some researchers suggest that physical movement in the rehearsal can benefit adolescent boys in musical, emotional, and developmental ways. Cooksey’s work includes various kinesthetic approaches designed to assist the adolescents with singing. Both Blackstone and Leck model moving the arm in an arc-like motion above the head and then downward to promote lifting into head voice, control of breath, and sustain of vocal line.68 From an emotional perspective—and perhaps a developmental one—Freer suggests that adolescent boys need to have multiple opportunities for physical movement during the rehearsal process.69 Barham even suggests the occasional use of choreography for boys at this age level.70

Maintaining a Healthy and Productive Rehearsal Environment

It is important for choral directors to create and maintain a positive and healthy rehearsal environment for adolescent male singers. Based upon the literature reviewed for this study, coupled with the author’s experiences, the following strategies are offered:

- create an environment of safety and trust so that the boys can be themselves;71

- allow the boys to move toward independence in their musicianship,72 including the monitoring of their own voices;73

- provide high standards and structure in the rehearsal;74

- be honest and tactful when responding to singers;75

- use positive reinforcement and encouragement to build self esteem;76

- demonstrate that singing is a worthwhile activity;77

- establish a peer support group within the ensemble;78

- exercise flexibility;79

- consistently promote healthy singing, which includes use of head voice, proper posture, and supported breathing;80

- be prepared to move the boy to another vocal part at the first sign of discomfort;81

- maintain open lines of communication, especially regarding vocal issues;82

- keep the rehearsal moving forward by shifting activities often, approximately every 10 to 12 minutes.83

Conclusion

This study presents a survey of strategies that can be used in the choral classroom when working with adolescent male singers. In addition to presenting the reader with some of the more prominent research-based techniques that exist in the literature, the author has attempted to present some of his own rehearsal strategies that have been derived directly from and supported by the research findings. The hope is that choral directors who read this study will not only be encouraged to implement the various techniques that have been outlined in the preceding pages, but also be inspired to develop and explore strategies and activities that will be applicable to their specific circumstances.

With the kind permission of Choral Journal, the journal of the ACDA. The article was first published in its April 2012 issue.

NOTES