Grant Gershon, Director of the Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale, USA

György Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna is one of the most extraordinary and iconic choral works of the 20th Century. Written in 1966, it is arguably Ligeti’s purest example of “microtonality”, a term and technique that he himself invented. The piece is scored for 16-part a cappella choir (SSSS-AAAA-TTTT-BBBB), with a typical performance lasting 9-10 minutes. It became well-known outside of the world of new music when Stanley Kubrick utilized part of it (famously unauthorized by the composer) in the film 2001 A Space Odyssey. With its other-worldly, disembodied atmosphere, it’s hardly surprising that Lux Aeterna would suggest to Kubrick the weightless and mysterious quality of deep space.

I have had the great pleasure of working on many of Ligeti’s vocal works over the years, and I am always struck by the combination of extreme rigor and creative fantasy in his compositional process. I’ve come to understand that with Ligeti, even more so than with most composers, the clearer a performer understands the compositional technique the more effectively one can rehearse and perform his music. There is no work of which this is truer than Lux Aeterna.

Compositional techniques and Guide to Rehearsing

Lux Aeterna is one of the most tightly constructed works in the choral repertoire. It is fundamentally a series of strict canons at the unison. The pitch material and sequence of each vocal part in the various canons is identical. Ligeti creates the cloud-like sonorities that characterize the piece by closely stacking the individual entrances of each vocal part, and by varying the subdivisions (and therefore the speed) of each individual line. For instance, in the opening section which is scored for the four soprano and four alto parts, S1, S4 and A3 are in permutations of septuplets, S2 and A3 are in quintuplets; and S3 and A2 are in sixteenths. Every vocal part is rhythmically independent, and the sense of time is obscured for the listener because the note changes very rarely occur on the beat. In fact, in a footnote on the first page of the score Ligeti requests that the singers “Sing totally without accents: barlines have no rhythmic significance and should not be emphasized”.

The large scale structure of the piece is essentially in four overlapping sections, each with its own unison canon:

| Lux Aeterna luceat eis | m1-37 | sopranos and altos |

| Cum sanctis tuis quia pius es | m39-88 | tenors and basses |

| Requiem aeterna dona eis | m61-79 | sopranos |

| Et lux perpetua luceat eis | m90-119 | altos |

Additionally, the basses have two brief homophonic moments, both on the word “Domine”. The first is in their highest falsetto range (m37-41), while the second (m87-92) “resolves” to a D# minor triad (the only such chord in the entire piece).

Once one understands these compositional principles, a strategy for rehearsing the piece becomes clear. I have created a two-page summary of the musical material which I call “Lux Redux”. Whenever I rehearse an ensemble in Lux Aeterna I distribute this to the singers in advance. I have found that utilizing this chart can save an enormous amount of rehearsal time, and it quickly makes the structure of the piece clear to the performers.

Because it’s critically important that each singer be absolutely confident with the pitch material, at the first rehearsal I ask the singers to refer to “Lux Redux”. We begin with all sopranos and altos singing the first section (“Lux aeterna…”) several times in unison on dictation. Once the intervals of this long line are secure, a useful next step is to practice overlapping the entrances like a round (i.e. S1/A1 begins, S2/A2 enters as S1/A1 sings their 2nd note, etc.). By doing this, the singers feel what it’s like to “hold their own” against the other neighboring notes, and some of the implicit harmonies begin to emerge. We can then work through the opening section as printed. We follow this same principle with tenors (“cum sanctis…”) joined by the basses (“…in aeternam”) and so on until we have worked through the whole piece. The goal of this process is for the pitch material to be secured with clarity and confidence. The more pristine the intervals are within each vocal line, the more the overarching magic of the vertical sonorities emerges.

Once this initial process of building absolute confidence with the pitch material is achieved, it’s easier to focus on the overall vocal color of the piece. The dynamic is sempre pp (with a few modifications from the composer to account for differences in vocal ranges), and Ligeti requests that the sound be “wie aus der Ferne” (from afar). For me the key to creating the most luminous quality possible is the opening [u] of “lux”. The placement and resonance of this vowel sets up the tonal color and focus for the entire piece.

As a conductor, the most important thing that we can do for our singers in this piece is to be crystal clear with our beat pattern, particularly making sure that the downbeat of every bar is apparent. I cannot overstate how easy it is for the singers to get lost; the entire piece is in 4/4 with no tempo changes, and no audibly discernable pulse. It’s important that each note change is smooth and un-accented, and that the singers stay within the framework of each bar. For the listener, the overall effect should be timeless and light-filled, just as the title suggests!

There are two notorious vocal moments in the piece. The first is the high falsetto passage for the basses at m37. As Ligeti suggests in a footnote, it’s more important to assign this to the most vocally appropriate basses and tenors than to insist that this be sung by B1-3. The other particularly challenging passage is the soprano and tenor high B (p possibile!) entrance at m94. Here I have the S3 sing the lower octave with S4, returning to the written S3 line in m100.

One final note: it’s very important for the conductor to continue lightly showing time through the final seven bars of the piece. Ligeti could easily have written a fermata on this silence. His decision to notate these seven bars of rest creates a beautiful sense of continued flow after the actual sound has long died away.

Conclusion

Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna is an extraordinary study in color and ambience. This work transports the listener to another sonic universe. A carefully and confidently prepared performance is fantastically rewarding and satisfying for singers and audience alike. My hope is that many more people will experience the wonder of this remarkable piece as we celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the birth of György Ligeti.

Grammy™ Award winning conductor Grant Gershon is the Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale, which is the “best-by-far major chorus in America” (Los Angeles Times). A passionate advocate for new opera, Gershon led the world premieres of John Adams’ Girls of the Golden West and Daniel Catán’s Il Postino. He has also led premieres of works by Esa-Pekka Salonen, Steve Reich, Tania Léon and Louis Andriessen, among countless others. Gershon worked closely with György Ligeti, preparing choruses for performances of Clocks and Clouds, Le Grand Macabre, and the Requiem. He has conducted Lux Aeterna many times, including for the grand opening of Walt Disney Concert Hall (broadcast on PBS Great Performances). Gershon’s discography with the LAMC includes recordings of music by Nico Muhly, Henrik Gorecki, David Lang, and Steve Reich. He has worked closely with many legendary conductors, including Claudio Abbado, Pierre Boulez, Simon Rattle, and his mentor, Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Grammy™ Award winning conductor Grant Gershon is the Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale, which is the “best-by-far major chorus in America” (Los Angeles Times). A passionate advocate for new opera, Gershon led the world premieres of John Adams’ Girls of the Golden West and Daniel Catán’s Il Postino. He has also led premieres of works by Esa-Pekka Salonen, Steve Reich, Tania Léon and Louis Andriessen, among countless others. Gershon worked closely with György Ligeti, preparing choruses for performances of Clocks and Clouds, Le Grand Macabre, and the Requiem. He has conducted Lux Aeterna many times, including for the grand opening of Walt Disney Concert Hall (broadcast on PBS Great Performances). Gershon’s discography with the LAMC includes recordings of music by Nico Muhly, Henrik Gorecki, David Lang, and Steve Reich. He has worked closely with many legendary conductors, including Claudio Abbado, Pierre Boulez, Simon Rattle, and his mentor, Esa-Pekka Salonen.

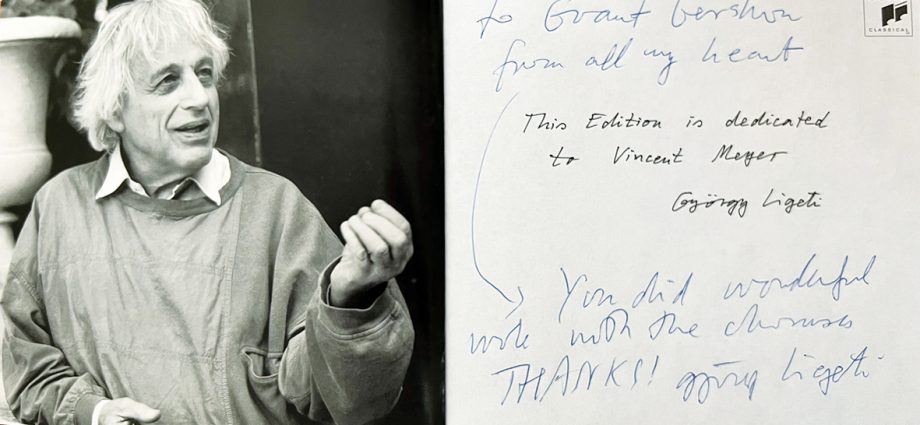

Head photo: CD booklet Le Grand Macabre, inscription from Ligeti to Gershon