A Different Musical Understanding

by Aurelio Porfiri, composer, conductor, writer and educator

How many conductors go deep into different ideas, understandings, hermeneutics, regarding the music they want to perform? I have already referred previously to the issue of “conductors’ culture”, an issue that is compounded by the fact that conductors tend to include in their choral programs pieces that are very different in style, often being unfamiliar with the pieces they have chosen. Of course I am not referring to all conductors, but there are some who perform music they know very little.

There is also another problem, related to this, concerning main performance practices. Sometimes we refer to performance practices which we think are untouchable, whereas this may not be the case. So it is certainly worthwhile to look at the work of musicologists who offer a different perspective that may help us tp broaden our horizons.

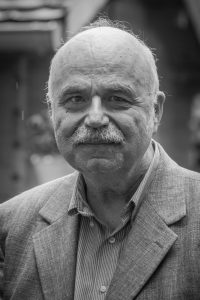

One example for me is certainly Jacques Viret (1943), a French musicologist of Swiss origins. He is currently Professor Emeritus at the University of Strasbourg, where he has been teaching since 1972. The supervisor of his PhD thesis (on Gregorian chant) was the famous French musicologist Jacques Chailley (1910-1999). Jacques Viret is the author of several books, including Regards sur la musique vocale de la Renaissance italienne (1992), La Modalité grégorienne, un langage pour quel message (1996), Les Premières Polyphonies, 800–1100 (2000), Métamorphoses de l’harmonie : la musique occidentale et la tradition (2005), Le retour d’Orphée: l’harmonie dans la musique, le cosmos et l’homme (2019).

Jacques Viret’s thinking is important because it puts us in direct contact with a meditation not on the past but on the origin of music. This difference between past and origin is very important, and it is relevant also for those who deal with music and the human voice: I would say especially for them. The past it is what happened before us; the origin is what has been happening through all eternity. We may say that the second concept is more spiritual, using “spiritual” in a broad sense. In Le retour d’Orphée he has said: “Our modern idea of music is influenced by the prevailing ideology, rationalist, Cartesian, analytic.” (my translation from French). It is important to reflect on this, because what Jacques Viret is teaching us is that we cannot reduce music-making merely to rules and techniques: “Bach’s Cantatas for dummies” or “Italian choral music at your fingertips”. Simplifying everything in this way may seem the best solution, a homage to American pragmatism; but pragmatism (the idea that thought is not a passive contemplation of ideas but a way to modify reality) has to be clearly understood. Thinking should not be just an abstract and solipsistic activity, but it can have no meaningful effect on reality if it has no meaningful support. We call this tradition. Jacques Viret is certainly a musicologist who values tradition as the base for understanding music. His research on the contacts between Gregorian chant and other monodic traditions coming from other religions is very interesting. In all his research he attempted to identify the contacts among all the musical traditions of the world, trying to identify common origins.

His ideas on Gregorian chant, which we must remember is at the base of Western music, are “heretical”. He admired the work done by the monks of Solesmes in reconstructing melodies, but he strongly condemned their interpretation as “romantic” and not faithful to the spirit of this repertoire. In an interview given to O Clarim in 2017, said he had this to say about his interest in Gregorian chant: “At the beginning, my interest was essentially in music: I wished to study the process of composing Gregorian chant – this was the subject of my doctoral thesis at Sorbonne University in Paris, written with the supervision of Jacques Chailley (1981). This research made me aware of folk music, “world music.” I became convinced that Gregorian chants are built on structures which are universal, a sort of musical archetype. There is nothing surprising in this, because when the monks of Solesmes founded Keur Moussa Abbey in Senegal in 1963, they heard local people singing traditional songs that resembled some of the antiphons and hymns in Gregorian chant. By adapting the shapes of these melodies, they composed a beautiful liturgical repertoire in French and Wolof (a local language), half chant and half African.” Viret’s research, as I have said, led him to disagree with the way the monks of Solesmes (an absolute authority on the study of Gregorian chant for most of the musicological community) present the interpretation of chant. In the same interview for O Clarim he stated: “The monks of Solesmes have restored the original melodic text of the repertoire corrupted in the seventeenth century, a considerable undertaking. But their style of interpretation is not authentic; it was too much influenced by the choral aesthetic of Romanticism and consequently destroyed the tradition of singers, a tradition which had survived until the nineteenth century.” This reference to the tradition of singers is interesting: the “chantres” interpreted Gregorian chant according to the definition of good singing given by St. Isidore of Seville: “sweet voices are delicate and full, clear and high-pitched” (translated by Priscilla Throop). The singing therefore should not be very soft but should make use of the full voice. Jacques Viret also studied traditional singing not only in the field of plainchant but also in polyphony, focusing his attention on the Sistine Chapel Choir tradition. He also turned his attention to traditions outside the Christian world, including the importance of music as a way to keep people healthy or to aid in recovering from illnesses (he also wrote a book about music therapy).

I had the pleasure and honor of writing a book with Jacques Viret, called Les Deux Chemins (2017). We are currently writing another book on modality, which we hope to publish in 2020. In Les Deux Chemins, Jacques Viret stated that music is “knowledge in the highest sense of the word, wisdom; it connects with things that are really essential, that is to say, spiritual. Traditional societies were aware of this, and we too were aware of it in our Western culture in ancient and mediaeval times. We have forgotten it.” (my translation). In the same book there is a profound meditation that should be considered carefully by every choral conductor: “Music exists only if someone hears it; physically there exist only aerial vibrations. Music is not in the sounds, it is in their relations. If we transpose a melody to bass or treble, it remains identical to itself while all its sounds change. This musical evidence, observed in 1890, engendered the psychology of form, Gestaltpsychology. Consciousness transforms aerial vibrations into sounds with a determined pitch and sonority, and into sound structures made coherent by the sounding phenomenon – harmony – which creates an interconnection between sounds. And this “someone” who hears music must be a human being with a human conscience, human thought, a human soul. A human memory too, because to perceive the musical meaning of a melody we must remember notes already heard. I imagine animals hear the sounds but they do not hear the music because they do not have a human mind. It is different for a painting or a sculpture, material objects existing independently of the subject. This is why music moves us more than a painting or a statue; it penetrates our inner being.” (my translation). Music is not in the sounds, Jacques Viret has stated, but in their relations; and is this not a definition also of a choir? A choir is not in this or that singer, but in their relations: if this relation is not effective then the choir, even if composed of very good singers, will never be a good choir. This is why it is often said that there are no bad choirs, only bad conductors, because the conductor is the one who should be able to listen, to fill the gap. And you can achieve this only if you are able to listen not just to your singers but also to the tradition from which a certain type of music comes. You need to be able to exercise your critical judgment and accept also different points of view, including that of Jacques Viret. It is neither necessary nor even important that you agree on everything; what is important is that your own ideas will be reinforced and improved through comparison and interchange with a different musical understanding.

Aurelio Porfiri is a composer, conductor, writer and educator. He has published over forty books and a thousand articles. Over a hundred of his scores are in print in Italy, Germany, France, the USA and China. Email: aurelioporfiri@hotmail.com

Aurelio Porfiri is a composer, conductor, writer and educator. He has published over forty books and a thousand articles. Over a hundred of his scores are in print in Italy, Germany, France, the USA and China. Email: aurelioporfiri@hotmail.com

Edited by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy/UK