Introduction

As Carvalho mentioned in a previous Dossier on Brazilian choral singing,[1]the large area of the country, the profound mixture of influences that come together to construct Brazilian culture (African, European and Indigenous Indian), and the diversity of musical styles make it nearly impossible to make any general statements regarding the country’s choral music. This article is, therefore, focused on five different aspects of choral life in Brazil and explores some of its peculiar aspects, in the words of music teachers, musicologists and choral directors, who touch on historical aspects of 20th-century music, the country’s public education agenda, youth choirs, choral arrangements and company choirs. Other important activities, such as community choirs, composers and choral festivals are left out of this article due to lack of space.

Orpheonic Singing[2]in Brazil until Villa-Lobos

Flavio Silva

The first attempts to establish music-making as a systematic activity in Brazilian schools seem to have been made by Barão de Macaúbas during the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1856 he wrote: “Nobody, nowadays, is unaware of music’s benefits in improving behaviors, making hearts more sensible, activating emotions and exalting patriotic feelings.” In 1888 he expressed the desire that “music was included among the required disciplines in the country’s elementary schools.”

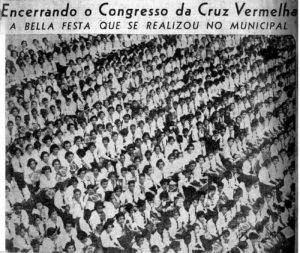

In São Paulo, at the beginning of the twentieth century, we find the first attempts at well-organized polyphonic collective singing activity, with or without instrumental accompaniment, a fact owed to João Gomes Junior and João Batista Julião. In 1921, local government authorized the Escolas Normais[3]to organize “orpheonic rehearsals” (Fuks: 100). Fabiano Lozano organized, in the city of Piracicaba, the Orfeão Piracicabano, which made several recordings and toured to Rio de Janeiro in 1925. In Pelotas, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Antonio Leal Sá Pereira prepared a 4-part version of the National Anthem, which was sung by the “Coro dos Mil” (Choir of the One Thousand) at the festivities celebrating the centenary of Brazil’s independence in 1922.

In Rio de Janeiro the foundation of a “Grande Coral Brazileiro” (Great Brazilian Choir) was suggested in 1882, but the idea does not seems to have caught on. In October 1926 the “Sociedade Coral Brazileira” made its debut, conducted by Luiz Marisa Smido, Bento Mossusunga and Eduardo Souto, on which regard the Revista Musical stated: “It is astonishing that an institution such as this hadn’t been established yet in Brazil.”

According to Rosa Fuks, in 1929 a committee constituted of Brazilian musicians and teachers such as Francisco Braga, Sylvio Salema and Eulina de Nazateth, was installed “to develop a music program [dedicated] to the educational establishments of the Brazilian capital [Rio de Janeiro, at that time] […] through choral singing and instrumental practice, both individually and collectively, a plan published in 1930” (Fuks: 114). But the bibliography she mentions does not make references to texts published after March 1930, in the Weco and Ilustração Musical periodicals, in which Luciano Gallet and, even more, Lorenzo Fernandez criticized the decline of Brazilian musical life due to the propagation of poor quality materials, for which they held responsible the wide distribution of recorded music, radio stations and even printed music editions. Orpheonic singing in schools was introduced then as the solution to this problem. These articles made a considerable impact in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. In March 1931, Lorenzo Fernandez published the detailed study “Choral Singing in Schools”, based on the premise that “it is necessary, before anything else, to train the classroom teachers appropriately.”

It has not yet been possible to find connections between the 1929 committee cited above and the criticisms made by Gallet and Fernandez, and between the publication of the 1930 plan (which bears no exact date) and the article “To React”, which Gallet published in March of that year.

Villa-Lobos comes on stage

It is well known that Villa-Lobos attended some remarkable choral concerts in Weimar and Barcelona during his second European tour. It is also likely that he got acquainted with the great French choral movement[4], through his contact with conductor Robert Siohan. Upon his return in the summer of 1930, he went to São Paulo. Available information indicates that his aim was to accumulate as much money as possible to enable him to return to Europe and continue his career as an artistic creator; “In the composer’s documents and statements until [the beginning] of 1932, there aren’t any hints of a desire to take over his role as an educator” (Guérios: 240).

Evidence suggests that in the second semester of 1930, the composer presented a musical education plan to Julio Prestes, then the country’s president (he was deposed by a revolutionary coup d’état in October of that same year). This plan is possibly the one criticized by the periodical Ilustração Musical in February 1931, for it foresees “the officialization of national musical life [… and …] prohibits the importation of foreign music [or requesting] its reduction to at least 50%.” This plan also stated that “the study of Brazilian music should be complete, starting with harmony; it should also include rhythm, melody, and counterpoint, until reaching the discussion of ethnicity and even the philosophical foundations that characterize it.” Less then two years after the composer took over the lead of the Brazilian choral movement, he abandoned these ideas.

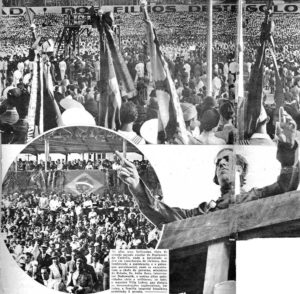

João Alberto, a great lover of music, Interventor[5]in São Paulo from November 1930 through June 1931, played an essential role in Villa-Lobos’s decision to stay in Brazil for longer. The information about the beginnings of their relationship is contradictory, but we owe to him the series of concerts Villa-Lobos gave, alongside other musicians, in several cities of São Paulo state between January and April 1931. Immediately after this, the composer proposed to the Interventor a great civic musical show – “The Villa-Lobos Civic Exhortation”, which was staged the following May and involved approximately 15 000 choral singers and band instrumentalists, a prelude to the great choral gatherings that took place in Rio de Janeiro after 1932.

Villa-Lobos returned to Rio de Janeiro at the end of 1931. In February 1932 the “Serviço Técnico e Administrativo de Música e Canto Orfeônico” (Technical and Administrative Service for Music and Orpheonic Singing), was created, and in the same month a document sent by the composer to Brazilian president Getúlio Vargas was published. In it, Villa-Lobos explained the difficulties faced by Brazilian musical activities. A few days later Villa-Lobos was invited by Anísio Teixeira to preside over that service. It is not impossible that it was João Alberto who suggested the composer’s name for that position. But it is certain that no-one else at the time would have had the expertise and the zeal to gather together the right personnel in order to, in such short time, reach such impressive results. In that position, Villa-Lobos no longer felt the urge to return to Paris, and, for the first time, ceased to depend on private sponsors and concert-giving to make a living. It was about time: at the end of 1932 he would complete 45 years of an errant life.

Sources:

- Luiz Heitor Corrêa de Azevedo:Música e músicos do Brazil

- Rosa Fuks:O discurso do silêncio

- Paulo Renato Guérios:Heitor Villa-Lobos

- Recortes do periódicos no Museu Villa-Lobos

- Revistas Weco e Ilustração Musical

Flavio Silva received his musical training in piano (Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre) and Musicology/Ethnomusicology (Sorbonne, Paris), where he wrote the dissertation “Origines de la samba urbaine à Rio de Janeiro”. He also graduated in Philosophy at the NationalPhilosophySchool in Rio de Janeiro. Mr. Silva is the Coordinator for Classical Music at FUNARTE, the Brazilian National Arts Foundation, where he oversees activities ranging from the preservation of historic music archives to the famed Bienais de Música Brazileira Contemporânea. He has published several articles and books, among which are “Camargo Guarnieri: o tempo e a música”, and the catalog of composer Francisco Mignone. Elected in 2008, Mr. Silva occupies chair number 28 at the Academia Brazileira de Música. He has two children, and is married to acclaimed Brazilian pianist Laís de Souza Brazil, also a member of the Academia. E-mail: flazil@terra.com.br

Flavio Silva received his musical training in piano (Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre) and Musicology/Ethnomusicology (Sorbonne, Paris), where he wrote the dissertation “Origines de la samba urbaine à Rio de Janeiro”. He also graduated in Philosophy at the NationalPhilosophySchool in Rio de Janeiro. Mr. Silva is the Coordinator for Classical Music at FUNARTE, the Brazilian National Arts Foundation, where he oversees activities ranging from the preservation of historic music archives to the famed Bienais de Música Brazileira Contemporânea. He has published several articles and books, among which are “Camargo Guarnieri: o tempo e a música”, and the catalog of composer Francisco Mignone. Elected in 2008, Mr. Silva occupies chair number 28 at the Academia Brazileira de Música. He has two children, and is married to acclaimed Brazilian pianist Laís de Souza Brazil, also a member of the Academia. E-mail: flazil@terra.com.br

Elza’s Recipe (or “The FUNARTE Panels for Choral Conducting”)

Samuel Kerr

The Choral Panels were a “magic” solution invented by Elza Lakschevitz when coordinating FUNARTE’s[6]Projeto Villa-Lobos. Through this series of events, in the 1980s, the Foundation intended to support Brazilian choirs and, in order to get acquainted with their needs, dreams and aspirations, Mrs Lakschevitz invited choral directors and singers to a meeting she named “The FUNARTE Panels”, an opportunity to float ideas, a space to share musical works, a place for reflection, where matters that interested the choral community would be discussed by Brazilian musical leaders.

It was a stunning success. Ten sessions of the Panels took place between 1981 and 1993, stimulating the work of choral directors from all Brazilian states, in an effort that kept Brazilian choral music so lively for a long time even after the meetings ceased. So significant was this movement that Mrs Lakschevitz’s initial gesture, supported by composer Edino Krieger and music educator Valeria Peixoto, started a new series in 2007 through the initiative of Eduardo Lakschevitz and the support of music educator Maria José Queiróz and musicologist Flavio Silva, which revived, in full flavor, Elza’s “recipe”.

But what did this recipe consist of?

Quite simple. Get together the country’s choral leadership to talk and discuss; then ask what matters should be discussed, exchanging information, always opening new spaces and shifting the focus of attention away from the large cities, attempting to reach the country as a whole. Great seasoning! An annual meeting, which became an event eagerly expected, awaited … and it tasted really good.

This was before the internet came along, and this opportunity for learning about singing techniques, choral repertory, new arrangements, rehearsal procedures and programming was an unique opportunity offered at the Panel meetings. As soon as registration opened, by telephone, telegram, telex machine and letter (I insist, there was no internet), places would be taken up very quickly.

The first session of the Panels took place in Rio de Janeiro in 1981, and the last one of that series in São Paulo, at USP[7], in 1993, after cities such as Brasília, Nova Friburgo, Vitória, Cuiabá, Londrina e Goiânia had hosted it. One year’s success would determine the direction the next one would take, however, always with Elza’s care in listening to what participants had to say and to suggest. In between the sessions of the Panel there were more experimental conducting courses and choral laboratories, where all ideas were tried out.

The recipe was constantly being reinvented, and Elza made sure not to dismiss certain important spices: prominent figures in Brazilian choral music would deliver speeches, teach courses and master-classes, or just take part in the meetings, sitting side by side with unknown singers or directors, fascinated by the camaraderie with people he/she knew only from their work and career, books written or by halls or auditoriums that had been named for them: among these people were Cleofe Person de Mattos, Nelson Mathias, José Vieira Brandão, Orlando Leite as well as many others, the mention of whom would exceed the scope of this article.

The recipe also included ingredients with made-up names, such as Sargento (the sergeant), Corão (the big choir), and Corel (the choral clothes line).

For each session a coordinator would be designated to take on the hardest job: trying to make everything happen on time! Oh! How difficult it was to cut short heated discussions, to interrupt a most interesting workshop, or to tell the Big Choir director that he/she had only five minutes of rehearsal time left! It was not easy for this coordinator, who was usually perceived as a rigid and unfriendly character and promptly compared to a sergeant trying to maintain discipline – There comes the sergeant to cut off our emotions!

Corão (Big Choir) was the great choral assembly. All participants, singers, directors would find themselves in the same ranks, under a colleague’s baton, developing a repertory to be presented at the end of that Panel session. If the works sung in each session of the “Big Choir” had been published, they would now make a great anthology. There were premières of original choral compositions and arrangements, written for, or dedicated to the Panels. Also, works that were otherwise rarely performed had their chances there, since it was fascinating for the director to have the opportunity to work with such a large and well-intentioned choir, and one with such good sight-reading skills! Even more usefully, the work of the big choir was also assisted by a voice teacher, Lúcia Passos, a pioneer at the time in embracing choral singing as her area of expertise. I recall her care in organizing the warm-up period right down to the detail of ending it in the key of the first song to be rehearsed by the director. I also recall the solutions for vocal issues she would come up with, all through rehearsals.

A lot of subjects, some difficult and even quite painful, experienced by directors and their choirs, were presented in those meetings, or in informal conversations. They ranged from labor contracts, rehearsal time for company choirs and difficulties in the recruitment of male voices, to copyright laws for public performances, recordings and score publishing, then an new topic of discussion in Brazil. Copyright issues were emerging during that time because it was a very difficult task to convince publishing companies to distribute choral works, as it was inconceivable having to pay composers’ copyrights for MPB[8]songs arranged and performed in concerts admission to which was nearly always free. Actually these were not new subjects, yet matters that needed new approaches.

Due to these still unsolved issues, all directors wanted photocopied arrangements of works still in manuscript format, because it would be hard to exchange repertory in any other venue. To facilitate this process, the “Corel” was installed (a combination of “cordel”, “coral”, and “varal”[9]). Yes, really, several clothes-lines were set up, where choral scores were exhibited to directors who would then order photocopies! But should we be reminded of this just now? I think so. Besides pointing out the mistake of photocopying, we must show the appropriateness of that practice that moment in time. The Panels propagated to the whole country the several and varied choral experiences of the different states. They made it possible for the Cordel’s voice to be heard everywhere. A voice in the Cordel would be multiplied by thousands of other singers!

Elza’s recipe also demanded a careful preparation of the oven, before any ingredients would be mixed together.

Yes, a long time before each session of the Panels, she would invite several choral directors to FUNARTE’s headquarters, in Rio de Janeiro, to analyze the program, choose the workshops, read letters and evaluation forms from previous Panel session participants. She would request suggestions regarding repertory that could fulfill the needs of choirs from all Brazilian states and regions. I recall taking part in this consulting process, together with the late conductors José Pedro Boéssio, Juan Serrano and Oscar Zander. It is good being able to remember them – and also to remember the late Marcos Leite. In 1985, the “Big Choir” sang a jingle he created for the Panels: Friburgo hosts choral music in the 5th. National Panel/ Music, musicians/Magic, magicians/There is sound in the air … Halleluiah!

Samuel Kerr has made his musical career in the field of vocal music, as a choral director, arranger, organist and teacher. He has directed, among others, the Coral Paulistano do Teatro Municipal de São Paulo, the São Paulo State University Choirs, which he founded, the Cia Coral, the Cantum Nobile Choral Association, the Medical Students Choir at the Santa Casa Hospital, the Madrigal Psichopharmacom, and several other ensembles. He has also been the director of São Paulo’s MunicipalMusicSchool and main conductor of São Paulo’s Municipal Youth Orchestra. E-mail: smkerr@terra.com.br

Samuel Kerr has made his musical career in the field of vocal music, as a choral director, arranger, organist and teacher. He has directed, among others, the Coral Paulistano do Teatro Municipal de São Paulo, the São Paulo State University Choirs, which he founded, the Cia Coral, the Cantum Nobile Choral Association, the Medical Students Choir at the Santa Casa Hospital, the Madrigal Psichopharmacom, and several other ensembles. He has also been the director of São Paulo’s MunicipalMusicSchool and main conductor of São Paulo’s Municipal Youth Orchestra. E-mail: smkerr@terra.com.br

Company Choirs

Eduardo Lakschevitz

In Brazil, the corporate world hosts an active choral life. A large number of companies, of different sizes, both public and private, sponsor choirs in which their employees take part as singers. Such activity is viewed as a moment of relaxation amidst a stressful day’s work, which benefits both employers and employees. Besides this fact, however, other aspects presented in choral music are considered by human resources analysts as being very similar to modern practices of corporative governance, such as the view of a choir as a group of people working together to accomplish a common goal. The choir rehearsal is pictured as an occasion where the usual corporate hierarchy fades into the background (in many companies managers and directors sing side by side with factory workers, aiming at a perfect blend of their voices), as an experience of team-work, and as an activity that, at the same time, requires flexibility from its participants and aptitude to consider the goals of the whole team. Companies are also motivated to sponsor employee-based choirs with an eye to creating or reinforcing a reputation for being an institution that works to supply social needs of the local community through culture endeavors.

Petrobrás (Petróleo Brazileiro SA), one of Brazilian largest conglomerates, is a pioneer in making a choir available to its workers. According to José Machado Neto, general coordinator of the company’s choral program, their first group was established in a oil plant in 1964. Today Petrobrás’ Institutional Communications Department runs 32 choirs, spread through its facilities all over the country. “Choral singing is a solid part of the company’s own culture, which involves both active and retired workers,” Machado Neto says. “Our biennial choral festival, where all groups get together in a large theater, is a prestigious event within the company.”

Brazilian company choirs offer a significant amount of work opportunities for choral directors. These musicians, however, face quite idiosyncratic situations. Often there isn’t enough rehearsal time (but that’s OK. Don’t all of us choral directors always want more rehearsal time?). Practice rooms are seldom ideal, and the choir frequently has to compete for space with business meetings. Singers are volunteers and usually not auditioned, an important factor to be considered, since the lack of music education in Brazilian schools for decades makes the company choir the first choral experience ever for many of the participants. Also, since the choir isn’t the core activity at the company, frequently singers miss rehearsals due to job-related tasks.

As contemporary corporations are driven by the pursuit of profit and results, and most of the time they expect the same attitude from the choirs they sponsor, the director needs to find ways to make the group work musically, while coping with the aspects described above. One’s flexibility in doing so can affect conducting gestures (inexperienced singers don’t usually understand traditional measure-beating patterns), and rehearsal techniques (sight-reading skills are absent, rehearsal time is scanty and song-teaching has to be very effective). Also, the vocal style of the singers is often similar to the one they regularly hear (usually urban popular songs), which is a very long way from the Bel-canto style. Although healthy vocal procedures are constantly sought after by directors in rehearsal, the production of what is usually considered a standard Western choral tone leaves space for vocal sounds better in tune with local contemporary culture, in which popular songs significantly outnumber the traditional classical repertory.

This trend can also be observed in the repertory choices made by directors, most commonly based on arrangements of Brazilian popular tunes. Indeed, these choices are crucial in the development of a company choir, for the group’s volunteer character, and the continuity of the singers’ participation in it, depends heavily on how the members relate affectively to the whole project, a process in which their connection with the songs they sing is crucial.

The improper balance of voices (usually many more ladies than gentlemen are involved), and the non-auditioned character of a company choir require a constant re-arranging and adapting of songs. A cappella singing is less common than the use of harmonic accompaniment, played mostly on electronic keyboards or acoustic guitars, since it facilitates the teaching and memorizing of the repertory. Instrumentalists in these groups are often experienced in popular music, for their duties also require musical flexibility, a feature they usually display in their regular gigs. Even more important than sight-reading skills is the instrumentalist’s ability to understand harmony, texture, and rehearsal timing. At a time when company choirs attract directors and music teachers as a work opportunity, the competencies and skills required for the job are not usually dealt with in regular undergraduate and graduate choral programs. As a consequence these have been among the most frequently discussed issues in recent short-term courses and workshops for choral conducting around the country.

Although a few theses and dissertations have been dedicated to company choirs in the past years[10], we are still waiting for a thorough quantitative research into this form of choral music, work that, when pursued, promises to deliver important findings for the benefit of the art of choral singing.

Dr. Eduardo Lakschevitz teaches History of Music at the FederalUniversity of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO). He holds a Doctorate in Music Education from the same institution, and a Master’s degree in Choral Conducting from the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC). A frequent guest teacher in Brazil and the United States, Dr. Lakschevitz has recently taught at SyracuseUniversity and WestminsterChoirCollege. He has developed corporate training programs through choral music in major Brazilian companies, in areas such as services, communications and education. He also serves as the pedagogical coordinator for choral music at FUNARTE (National Arts Foundation). His compositions and arrangements are published by Alliance Music and Colla-Voce. E-mail: edulx@me.com

Dr. Eduardo Lakschevitz teaches History of Music at the FederalUniversity of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO). He holds a Doctorate in Music Education from the same institution, and a Master’s degree in Choral Conducting from the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC). A frequent guest teacher in Brazil and the United States, Dr. Lakschevitz has recently taught at SyracuseUniversity and WestminsterChoirCollege. He has developed corporate training programs through choral music in major Brazilian companies, in areas such as services, communications and education. He also serves as the pedagogical coordinator for choral music at FUNARTE (National Arts Foundation). His compositions and arrangements are published by Alliance Music and Colla-Voce. E-mail: edulx@me.com

Choral arrangements of Brazilian Popular Music

Eduardo Fernandes

Arrangements of popular tunes are, nowadays, an essential part of Brazilian choirs’ repertory, but one that hasn’t been receiving enough attention from scholarly research. The musical and cultural importance of the works produced (scores) and the people who write them are yet to receive proper recognition.

The arranging of popular tunes is an awkward grey area, since it has its origins in a mass production medium (connected to the idea of cultural industry), while at the same time making use of a classical expression vehicle (high culture), the choral ensemble. Such hybridism on the one hand opens up to the arrangement the privilege of involvement with two important streams of contemporary culture, and on the other bears the curse of not being accepted by either of these sides.

A bit of history

The late 1960s represented an important historical moment for Brazilian popular music production. The success of the Song Festivals promoted by several TV stations, which attracted the attention of great sections of the population, from the middle-classes through to the politically aware university students, brought mass culture and high culture closer together, represented here by young composers connected to universities. Besides, the political situation was delicate – there was a military dictatorship governing the country – and the questioning of established social values was of great significance to the agenda of these intellectualized young people.

In such a turbulent environment, taking part in a choir was one of the few ways open to these youngsters to spend time together, to feel part of a group. However, Western traditional repertory (represented by both European music and traditional-sounding Brazilian folk-music arrangements) found itself distant from the urban reality and young people’s aspirations at the time.

During this time the arrangements by Damiano Cozzela started to be performed and promoted more methodically, by the CORALUSP (University of São Paulo Choir). The rise of urban popular music arrangements for choirs, then, came to bring the choral experience closer to the young people’s regular daily lives, since participants started to sing in their groups the same songs they would listen to on the radio and television.

Nevertheless, this integration was not peaceful, for the classical music world’s criticism dealt harshly with this new style of choral music, and with the directors who were working with it. Maestro Benito Juarez reports that in a particular CORALUSP concert which he directed at São Paulo’s Municipal Theater (home of one the city’s symphony orchestras), performing a mixed repertory (traditional Western music and arranged popular songs), part of the audience wore black, stating their “mourning for the death of serious concert music”.

The adoption of this repertory made an impact that extended beyond purely musical and technical issues. It forced choirs to search for a way of developing performance practices that reflected more accurately the music being sung, leading some groups to create a less formal and more theatrical presentation of their work, the embryonic version of a style that came to be called coro cênico (scenic choir[11]), at the hands of a medical school choir (Coral da Faculdade de Medicina da Santa Casa de São Paulo, directed by Samuel Kerr), and later on by the work of an English language school choir in Rio de Janeiro (Coral da Cultura Inglesa, directed by Marcos Leite).

The choir, a space for diversity

With the exception of some choirs that are formed by people sharing a particular profile (age, ethnicity, religion and other criteria), most amateur choral ensembles bring together singers of varied ages, as well as social, cultural, and economic levels, a fact that confers to a choir a vast range of cultural and aesthetic references which most certainly will be reflected in the group’s style of singing, repertory choice and attitude on stage. Therefore it is valid to affirm that not only does the popular music arrangement bear the hybrid character mentioned above, but amateur choral activity as a whole is immersed in this specificity, a fact that can be observed in its physical constitution (the singers), performances practices, and the final presented product.

The vocal issue

Specific repertory needs particular solutions. A choral group that usually performs opera choruses won’t necessarily have the same results when singing popular songs, or folkloric ones, in spite of all its technical skills. It is essential to understand that each kind of music style has its idiosyncrasies and the vocal techniques employed should aim at reflecting the sound quality expected for each different kind of music style.

Marcos Leite summarizes the issue precisely:

When voice students look for basic knowledge, it is quite common that they take lessons with singers that teach in the lyric style, which is great, as long as vocal technique isn’t confused with aesthetic purpose, with a manner of singing that belongs to other repertories. […] at this moment one can perceive a severe misunderstanding by singers who, unaware of these issues, sing Brazilian music using the bel-canto sound.[12]

This kind of confusion can be linked to the training of choral directors (and also vocal coaches), still mainly classical, based in the European tradition. The few books on choral conducting published in Brazil make almost no references to the direction of urban popular music in a choral setting. The establishment of undergraduate courses in Brazilian Popular Music is still very recent, but these promise to be fair mediators between the two traditions mentioned in this article. Also, the great majority of vocal coaches that work with choral singers have studied according to the bel-canto tradition, which therefore makes a very large number of choirs pursue a sound quality that bears no resemblance with the original Brazilian popular music sonority. Some books published in the last years, such as Leite’s and Goulart and Cooper’s[13], musicians active both in the popular and the classical fields, are very welcome, for they are starting to fill this gap.

MPB arrangements, one more possibility

The choral arrangement of popular tunes represents a rich aesthetic experience for choral singers, since it offers information that already belongs to their vocabulary (the original song) and at the same time opens a new horizon of possibilities through the multi-voice re-elaboration of that song. The same holds true for audiences who discover new ways of hearing, perceiving and understanding a previously known song.

A good arrangement can easily carry the same structural complexity as does an original composition, since the composers/arrangers are able to employ several compositional resources in their quest to bring new ideas to the original tune. Moreover, the Brazilian popular song is reputedly one of the world’s most interesting and complex ones, both in its music and its lyrics, which makes its use as a source of inspiration for musical re-creation a natural and intelligent move.

Eduardo Fernandes teaches choral conducting at the UNIFIAM/FAAM, and directs the CORALUSP XI de Agosto, the UNIFESP Choir and the Fine Arts University Center Choir. He holds a Master’s Degree in Music (São PauloUniversity), awarded for a dissertation on “Vocal arrangements of popular music in São Paulo and Buenos Aires”, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Performance – bassoon (University of Campinas). Mr. Fernandes has been invited as a guest teacher at several courses throughout Brazil, including: Laboratório Coral de Itajubá, Fórum Rio a Cappella de Música Vocal and Painel FUNARTE de Música Coral. His main area of research focuses on the applications of body percussion sounds and movements on choral singing. E-mail: dufer@terra.com.br

Eduardo Fernandes teaches choral conducting at the UNIFIAM/FAAM, and directs the CORALUSP XI de Agosto, the UNIFESP Choir and the Fine Arts University Center Choir. He holds a Master’s Degree in Music (São PauloUniversity), awarded for a dissertation on “Vocal arrangements of popular music in São Paulo and Buenos Aires”, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Performance – bassoon (University of Campinas). Mr. Fernandes has been invited as a guest teacher at several courses throughout Brazil, including: Laboratório Coral de Itajubá, Fórum Rio a Cappella de Música Vocal and Painel FUNARTE de Música Coral. His main area of research focuses on the applications of body percussion sounds and movements on choral singing. E-mail: dufer@terra.com.br

Youth Choirs in Brazil[14]

Patricia Costa

Although choral music is a great educational instrument for any age group (quite apart from its obvious role as an effective aid to music education), it is still an activity devoid of appeal to most Brazilian teenagers. The prejudice behind the word “choral”, perceived in research recently concluded, was confirmed by authors, choral directors and by the young singers themselves.

In this research, the use of choral music as an educational tool was the argument to support the idea of including this musical practice in the high-school curriculum. However, the answers also suggested very clearly an urge to a more specific approach in the training choral directors receive, so as to allow them to understand more fully the particular issues of a school choir.

The idea of approaching conductors through semi-structured interviews was an important decision in order to start closing the gap caused by the lack of published materials on Brazilian high-school choral activities. Besides, this dissertation started to compensate for the poor communications and lack of exchange of experiences among directors of youth choirs, also mentioned by the majority of those who responded to the questionnaire.

Judging by the small number of responses, it is clear that there is so far little scholarly expertise in this field in Brazil. Likewise, the difficulties experienced by students who took part in this project in finding choral directors working specifically with teenagers, shed some light on the very small number of choral groups catering for this particular age-group, as had been suspected even before the beginning of the survey.

With the use of these answers, it was possible to confirm some aspects observed in my own experience as a choral teacher, such as:

- The training of a choral director and that of an educator bear a close relationship, for the great majority of directors have music education degrees.

- The main reference for choral directors in Rio de Janeiro is Professor Carlos Alberto Figueiredo.

- Most directors are not usually members of choral associations or similar groups.

- A large number of directors take part in short-term courses and workshops throughout the year, which points to a need to complement and update their training in the regular school curricula.

- Choral music is not always respected by the directors’ peers. Answers often mentioned prejudice, jealousy, and even indifference regarding it.

- Problems related to vocal malfunction were mentioned by a large number of directors. All of these, however, usually look immediately for medical treatment, when in this situation.

- The average age of the youth choirs researched varied, attesting to the difficulty of establishing cut-off ages between children’s and youth choirs. Some answers also showed a mix-up between the concepts of “children” and “teenagers”, which sometimes seemed to denote the same idea, a fact that created the “infanto-juvenil”[15]choirs, a discussion of which would exceed the scope of the research.

- With the exception of church groups, there is a significant drop-out rate in youth choirs when compared to ensembles of other ages.

- The singers’ high attendance level at rehearsals suggests their efforts and pleasure in taking part in such activity.

- High-school music directors need to plan their activities very carefully, respecting periods of exams, vacations, public holidays and all other aspects of the school calendar.

- Brazilian Popular Music is the repertory adopted by most of the choirs researched, in which case singers usually suggest the songs to be used.

- Most of the time the choral arrangements for those songs are written by the directors themselves, who have acquired this skill empirically or through short-term courses, which shows that either the presently existent repertory isn’t really suitable for youth choirs, or that there is an urgent need for innovation in the music regularly offered to these groups.

- The goals and objectives of these choirs often touch upon non-musical aspects, such as evangelization, promotion of the sponsor institution, as well as social and pedagogical aspects, the latter the most frequently cited one.

- Establishing an aesthetic conception of the groups doesn’t figure as an important issue. Indeed, most of the interviewees got confused with that idea. Some, however, related it to the choir’s sound quality. Through these respondents it was possible to establish a clearly marked dichotomy between the “traditional choir” (sings Western traditional repertory) and the “popular choir” (sings popular song arrangements).

- Collective creation procedures were attested to by many youth choir directors, although very seldom mentioned by directors of other choirs.

- A good proportion of the directors adopts, or at least considers adopting, scenic resources in their work.

- Regarding complaints about youth choir activities, the answers produced were common among many of the directors: lack of investment, lack of discipline, and irregular attendance at rehearsals. It can also be observed that many directors expect from their singers a behavior similar to that expected from adults, suggesting, again, that their training should also consider how to deal with this particular age group.

- The major satisfaction mentioned by choral directors is connected to non-musical issues, such as their joy, energy, will, vivacity, and creativity within their work, alongside their new discoveries and acquired knowledge about transformations inherent to the adolescent age.

- The way a director views the teenage singer also brought significant answers concerning the non-musical aspects of their teaching already mentioned above. Among the gains listed are the development of workgroup skills, improved self-expression, increased sensitivity, the ability to fight prejudice and to face challenges, as well as the possibility of leading a better life in future.

The vast majority of Brazilian youth choirs adopts accompanied repertory, mainly with the piano. But the fact that a cappella singing is so scarce can interfere with the general musical development of these ensembles, as the insistence on instrumental harmonic accompaniment can create a dependent attitude in the singer, diminishing his/her awareness of tuning, individually as well as in relation to the other singers.

Although belonging “only” to the popular music realm, the large-scale production of choral arrangements of these songs contributes to a revival of choral activity, attracting teenagers to – or, at least, not repelling them from – collective singing.

Scenic and theatrical exercises were mentioned as one of the instruments used to involve youngsters more closely in choral activity. In a moment of self-discovery, the insertion of exercises that put teenagers in touch with the expressive possibilities of their bodies proves to be a powerful resource to their development as singers.

Finally, the research analyzed elements that might fit a choral program and, at the same time, awaken the urban teenager’s interest towards expressive choral work. It was shown that the scenic apparatus also promotes a more profound relationship between singers and the interpretation of the repertory proposed, either by the detailed study of the poetry in each piece, or by the scenic environment created, and even by means of physical awareness as an aid to perceiving more accurately the group’s musical propositions.

Choral director, arranger and scenic director, Patricia Costa holds a Music Education Degree (1996) and a Master’s Degree (2009) in Music Education, from the FederalUniversity of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), for research into different conducting approaches to youth choirs. Author of several articles on the same topic, Mrs. Costa directs the choral programs in two schools: Colégio Cruzeiro and São Vicente de Paulo, a choir which, under her direction, won the First Prize at the II FUNARTE National Choral Contest in 1999. She is a frequent guest teacher at the Brazilian Conservatory of Music (Rio de Janeiro) and at the FederalUniversity’s Fine Arts School, in Paraná. E-mail: pccantocoral@gmail.com

Choral director, arranger and scenic director, Patricia Costa holds a Music Education Degree (1996) and a Master’s Degree (2009) in Music Education, from the FederalUniversity of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), for research into different conducting approaches to youth choirs. Author of several articles on the same topic, Mrs. Costa directs the choral programs in two schools: Colégio Cruzeiro and São Vicente de Paulo, a choir which, under her direction, won the First Prize at the II FUNARTE National Choral Contest in 1999. She is a frequent guest teacher at the Brazilian Conservatory of Music (Rio de Janeiro) and at the FederalUniversity’s Fine Arts School, in Paraná. E-mail: pccantocoral@gmail.com

[1] Carvalho, Edson. Looking into the Future: Perspectives on Choral Life in Brazil.International Choral Bulletin, vol. 1, 2003.

[2] Orpheonic singing originated in France in the early nineteenth century: large choral groups whose membership was drawn primarily from the underprivileged sections of the population. Brazil took over this movement, applying it to schools, whose efforts would often culminate in major festivals where many such groups met to sing in enormous choirs.

[3] Teacher training colleges

[4] see footnote 2

[5] A type of state governor nominated by the revloutionary government.

[6] Fundação Nacional de Arte, a Federal institution devoted to the promotion of Brazilian artistic and cultural affairs.

[7] The University of São Paulo.

[8] MPB stands for Música PopularBrazileira, a style of Brazilian urban popular songs largely arranged for choral singing.

[9] Cordel: a stile of popular literature, typical of the Northeast part of the country;Coral: same as choral;Varal: clothes-line.

[10] Morelembaum, Eduardo.Coral de empresa: um valioso componente para o projeto de qualidade total. Dissertation. ConservatórioBrazileiro de Música, 1999; Teixeira, Lúcia.Coros de empresa como desafio para a formação e a atuação de regentes corais: dois estudos de caso. Dissertation. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2005; Rocha, Elen Regina Lara.Atuação do músico em empresas: mercado, indicativos e processos. Dissertation. Universidade Federal de Goiás, 2007; and Lakschevitz,Eduardo.A common chant: perceiving the company choir as an art world. Thesis. Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2009.

[11] Choirs that use theatrical movement in performance. Not to be confused with the idea of a choreographed show-choir.

[12] LEITE, Marcos, &ldquoMétodo de Canto PopularBrazileiro.Ed. Lumiar, Rio de Janeiro, 2001, p.4.

[13] GOULART, Diana. &ldquoPor todo canto&rdquo: coletânea de exercícios de técnica vocal /Diana Goulart , Malu Cooper. Rio de Janeiro, D. Goulart, 2000.

[14] This article is extracted from my Master&rsquos Dissertation, concluded in July 2009, at UNIRIO (Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro), with added data from ongoing research via the internet, in which the same topics are investigated further.

[15] Choirs that mix children and teenagers.

Dossier revised by Irene Auerbach, England

Curriculum vitae revised by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy