By Philip Copeland, Choral Conductor and Teacher

This is the second article in a two-part series about American composers born after 1980. For many years, Eric Whitacre, along with Morten Lauridsen, dominated the landscape of choral composition in the United States. In recent years, other composers have emerged and their thoughts and ideas have found a foothold. Three composers were featured in the first article: Ted Hearne (b. 1982), Jake Runestad (b. 1986), and Nico Muhly (b. 1981).

For this article, I crowd sourced choral conductors from ChoralNet, Facebook, music publishers, and other creators of music. My goal was to identify outstanding young composers and it was not an easy task. Several friends took issue with my arbitrary birth date of 1980; others decided that my first batch of composers was not representative of women and didn’t identify composers of different ethnic origins. There were many composers that fit my criteria of “born in 1980 or later,” but I was not able to include them all.

In the end, I identified four composers to discuss in this article: Zachary Wadsworth (b. 1983), Michael Gilbertson (b. 1987), Dominick DiOrio (b. 1984), and Sydney Guillaume (b. 1982). They are presented here in no particular order.

Zachary Wadsworth (b. 1983)

www.zacharywadsworth.com

Zachary Wadsworth is an innovative composer for choir and a new faculty member at Williams College, a private liberal arts college in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Composer James MacMillan was one of the first to bring attention to Wadsworth’s choral music through his service as the Final Adjudicator of the King James Bible Composition Awards, a competition that was created to help celebrate the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible. This recognition brought significant attention to Wadsworth’s music; it eventually resulted in a commission from Choir & Organ magazine and an ongoing relationship with Novello. Wadsworth’s winning composition, Out of the south cometh the whirlwind, has been described as a “highly imaginative and compelling addition to the choir and organ repertoire and it would serve as an unusually dramatic and arresting anthem at Evensong.”

Wadsworth names Arvo Pärt and Luciano Berio as significant influences in his choral style but names his teacher Steven Stucky as the greatest influence on his choral music. In particular, he admires Stucky’s ability to bring the same elegance and technical wizardry to his choral music as he does to his chamber and orchestra works.

Wadsworth believes that “the best choral works feel like tidy little universes, in which text and music support a central, resonant emotional message.” In creating these worlds of sound, he often employs the compositional devices and forms of previous centuries. His compositional dialect and harmonic language, however, is completely modern.

Two works demonstrate the compositional prowess of Wadsworth and this fusing of new and old: Beati Quorum Remissae (Alliance Music Publishing, AMP0729) and Spring is Here (available at composer’s website).

In Beati Quorum Remissae, Wadsworth uses both text and music to support a central emotional message of penitence and forgiveness. In it, the composer reworks the order of the verses of Psalm 32. Instead of beginning with verses of praise, as the psalmist did, Wadsworth starts with lament and progresses towards deliverance. To aid in this movement, the composer utilizes a small second choir that offers hope and encouragement to the larger choir singing the words of despair.

This double-choir work resembles Benjamin Britten’s Hymn to the Virgin with its smaller second choir that sings only in Latin. Britten’s use of the double-choir, however, was to provide commentary on the English text. Wadsworth uses the second choir’s Latin text to influence the speaking voice of the first choir; it functions as a dramatic aid to encourage hope.

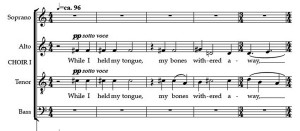

Wadsworth captures the plaintive feeling of the psalm with perfect fourths and occasional dissonance. Both techniques are effective, both in general mood and specific word painting; they also clearly suggest the influence of Arvo Pärt. See m. 1-5 (Example 1).

Example 1, ‘Beati Quorum Remissae,’ m. 1-5.

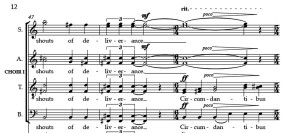

The composer beautifully illustrates the climax of the work, using the full range an sonorous potential of the choir in painting the text “shouts of deliverance,” shown here in Example 2.

Example 2, ‘Beati Quorum Remissae,’ m. 47-49.

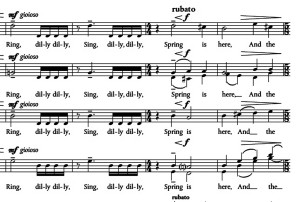

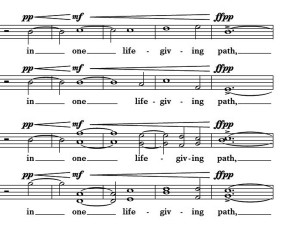

Wadsworth fuses old and new again with his Spring is Here. In this composition, he employs the Renaissance madrigal form to set a text by Duncan Campbell Scott (1864-1957) entitled “Madrigal.” In this work, the composer recalls many traditional features of the madrigal form in this 21st-century reincarnation, including strophic form, text painting, nonsense syllables, a lighthearted text, syllabic text setting, and a mostly major-key tonality.

The composer easily brings the Renaissance compositional form into the twenty-first century. The first four measures demonstrate the variety of compositional devices used to set the Scott poem: a melody that features disjunctive motion, mixed meter, and a succession of varying time signatures. Although complex, it is very clean writing; the vertical harmonies unfold logically from the leaping melody and the text falls naturally into the supplied rhythm. (Example 3)

Example 3, ‘Spring is Here,’ m. 1-4.

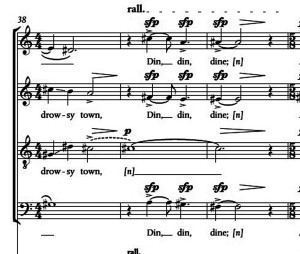

The long-cherished device of text painting makes frequent appearances in this composition, especially with the use of portamento sliding on the words “drowsy town,” followed by what appears to be a clock chiming the hour, shown here in Example 4:

Example 4, ‘Spring is Here,’ m. 38-40.

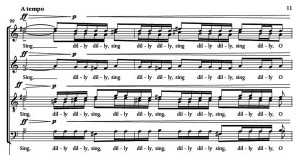

The work is regularly punctuated by modern versions of nonsense syllables supplied by the poet, a recurring technique that solidifies the tie to the Renaissance madrigal form as well as supplies unity to the work. (Example 5)

Example 5, ‘Spring is Here,’ m. 49-52.

The nonsense syllables help bring a convincing and exciting climax to the madrigal, shown here in Example 6:

Example 6, ‘Spring is Here,’ m. 99-101.

Zachary Wadsworth’s music is characterized by a high degree of compositional skill and his growing body of work spans a large range of emotional spaces. Like his music, Wadsworth’s website is professional and easy to navigate; there is much to explore and consider. On his webpage, he breaks his choral compositions down into skill level and distinguishes between sacred and secular. Conductors of advanced ensembles will want to consider, in addition to the works presented in this article, his To the Roaring Wind, a thoroughly contemporary work that sets Wallace Stevens’ poem of the same name. Church musicians will want to explore his hymn setting of Immortal Love, Forever Full to the tune Calgary.

© Zachary Wadworth. All rights reserved.

Michael Gilbertson (b. 1987)

www.michaelgilbertson.net

Although not yet thirty years of age, Michael Gilbertson is a remarkably well-performed and high-achieving composer from Dubuque, Iowa. He is active in a number of musical genres with significant works for ballet, opera, wind ensemble, and orchestra. Gilbertson is an extremely well-trained composer with an impressive pedigree of mentors. He is a prodigious composer; his hometown symphony orchestra has been performing his work since he was fifteen years old.

The remarkably talented Gilbertson is not a prolific choral composer, but he seems set to expand into the genre. The composer frequently collaborates with Kai Hoffman-Krull and has produced two choral works, Where the Words Go and Returning. Gilbertson seeks to engage with pre-existing works and composers from the past, as in his re-settings of three texts that were originally set by John Dowland. This set, called Three Madrigals After Dowland, sets three texts: Weep You No More, Burst Forth, My Tears, and Come, Heavy Sleep.

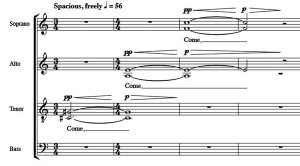

Gilbertson seems to prefer a stark declamation of text; much of his choral music utilizes the open fifth interval at the very beginning. (Example 7 and 8)

Example 7, ‘Come, Heavy Sleep,’ m. 1-4.

Example 8, ‘Where the Words Go,’ m. 1-5.

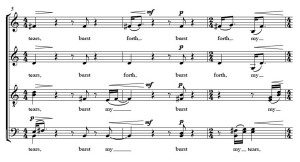

Gilbertson’s Burst Forth, My Tears is a more rhythmic work than the other two madrigals. In this piece, the composer sets up a driving rhythm in the choir and pairs it with soaring soprano soloists. He brings a glorious dissonance to the soloist’s declamation of the text, usually approaching it from a consonant interval. (Example 9 and 10)

Example 9, ‘Burst Forth, My Tears,’ m. 5-7.

Example 10, ‘Burst Forth, My Tears,’ m. 8-10.

Gilbertson has recently completed a larger work for double choir that was premiered by Musica Sacra at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York. Many call this work his “best piece” and it is his most substantial choral work so far. This twenty-minute work once again sets the texts of Hoffman-Krull in an exploration of love, regret, and remembrance through a conversation between the biblical characters David and Jonathan.

The composer’s work is frequently performed by professional chamber groups, including performances by The Crossing (Donald Nally), and The Esoterics (Eric Banks) later this year.

© Michael Gilbertson. All rights reserved.

Dominick DiOrio (b. 1984)

www.dominickdiorio.com

Dominick DiOrio seems to be everywhere and everything in choral music these days. His influence takes many forms: composer, advocate, conductor, presenter. He is first and foremost a composer, and he was recently named the 2014 winner of The American Prize in Composition, where he received praise for “his depth of vision, mastery of compositional technique, and unique style” which “set him in a category by himself.”

Part of DiOrio’s unique style is the philosophy of virtuosity that he employs in his compositions, an approach that can play out in a number of ways. Often, the technique appears in the accompanying instruments, but it may also appear in solo voices that accompany the choir or in the choral parts themselves. For DiOrio, the “element of virtuosity is key, as it presumes that the chorus I am working with is fundamentally an ensemble of skilled vocal musicians. Of course, amateur ensembles can (and do) sing this music as well, but it demands the very best of their musical abilities with regard to counting, pitching, intonation, vocal stamina, and dynamic range.”

The composer has a large body of work for choir, including works for large ensemble, chamber ensemble, unaccompanied choir, and accompanied works with solo instrument and solo keyboard. Two of his works are featured here: O Virtus Sapientiae (2013), a cappella with three soprano soloists, and Alleluia (2013), for choir and marimba.

DiOrio was first trained as a percussionist, so it comes as no surprise that he finds rhythmic complexity compelling. In his words, he wants “to create an elastic sense of rhythm in many of my works, using all of the inner combinations of the beat (duplets, triplets, divisions of 4, 5, 6, and 7), oftentimes working together in an accelerating or decelerating context (2, 3, 4, 5).” This sense of complexity, along with his interest in writing for virtuosic percussion and choir make an appearance in his Alleluia.

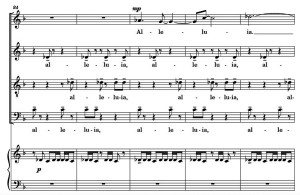

The work opens with bold fortissimo statements by the full choir, followed by driving marimba accompaniment at a quick tempo. (Example 11)

Example 11, ‘Alleluia,’ m. 8-12.

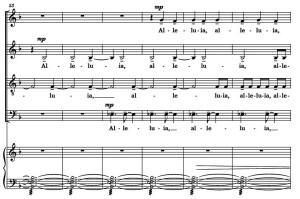

The driving rhythm subsides somewhat in the middle of the piece, but the rhythmic complexity continues in the voices, albeit in more subtle form. (Example 12)

Example 12, ‘Alleluia,’ m. 53-58.

The writing features both driving marimba and rhythmic complexity towards the end of the work. (Example 13)

Example 13, ‘Alleluia,’ m. 83-88.

DiOrio is such an advocate for contemporary choral music that one may be surprised that he prefers to sing the music from the past, composers that include Lassus, Bach, and Mendelssohn. DiOrio believes that these composers of the past and masters of counterpoint have much to teach the emerging composers of today. Instead of investing in lessons from the past, he feels that “much of today’s compositions look like they were written with two hands at the keyboard instead of conceived to be individual singing lines.”

O Virtus Sapientiae is a work that brings attention to music from the past; it features the chants of Hildegard, a divided SATB choir, and three solo sopranos. The placement of the performing forces is important in this work; it is meant to enact the drama of Hildegard’s visions. The three solos are positioned North, South, and West corners of the performance space while the larger chorus resides in the East.

At the beginning of the work, three soprano soloists present a slightly modified version of the original Hildegard chant featuring the Latin text O Virtus Sapientiae. DiOrio’s presentation of the chant increases in complexity each time; the second entrance features the original chant in a canon of three voices at the unison, while the third presents the original chant accompanied by augmented versions of itself. (Example 14) The three versions are an excellent example of DiOrio’s creativity and fascination with the potential of a single melody.

Example 14, ‘O Virtus Sapientiae,’ m. 15-19.

The divided choir answers each version of the chant with an English translation of the Latin text in a homophonic organ-like accompaniment throughout the first half of the work. (Example 15)

Example 15, ‘O Virtus Sapientiae,’ m. 21-25.

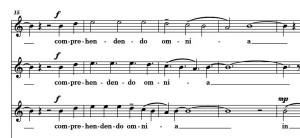

In the second half of the work, the soloists and choir switch languages and the three soloists become much more virtuosic in nearly-strict imitation. From this imitation, DiOrio is able to create intricate rhythmic complexities. (Example 16)

Example 16, ‘O Virtus Sapientiae,’ m. 45-46.

At the climax of the composition, the lower voices of the choir take on some of the virtuosity of the soloists’ earlier parts while the soloists become more beat-oriented and homorhythmic. (Example 17)

Example 17, ‘O Virtus Sapientiae,’ m. 63-64.

Composer DiOrio is many things, but his primary job is as Assistant Professor of Music at the Jacobs School of Music of Indiana University. In addition to his teaching in composition, he conducts NOTUS, an ensemble dedicated to the music of living composers. They premiere works of students, emerging composers, and established masters of modern composition. Recently-featured younger composers include Jocelyn Hagen, Michael Gilbertson, Texu Kim, Tawnie Olson, Zachary Wadsworth, and Caroline Shaw. This group was recently featured as the ensemble-in-residence for the composers track at the 2014 National ACDA Conference.

Through his work with NOTUS, Dominick DiOrio seems to be evolving into an influential figure among younger American composers. At the same 2014 ACDA National conference mentioned above, he presented an interest session called “Thirty-Something: New Choral Music by Today’s Hottest Young Composers.”

Sydney Guillaume (b. 1982)

www.sydneyguillaumemusic.com

Sydney Guillaume is originally from Haiti and immigrated to the United States in his youth. A graduate of the University of Miami, he currently lives in Los Angeles, California. His compositional style shows influences from Haiti and he frequently uses texts that are a combination of Haitian Creole and French. Guillaume has an intimate connection to the texts that he chooses; most of them are settings of poetry by his father, Gabriel T. Guillaume.

As a composer, Guillaume is well known in the world of American choral music. His music has been performed by university choirs, including the University of Miami Frost Chorale and Westminster Chorus, and professional choirs, including Seraphic Fire and the Nathaniel Dett Chorale.

The Westminster Chorus recently featured Guillaume’s Gagòt on the ACDA Western Division Conference. Composed for TTBB choir, the work sets Gabriel Guillaume’s poem of messy frustration, entanglement, and redemption. It is a powerful text that captures the frustration of everyday life, where “everything is entangled: pain and woe, doubt and faith, disgust and hope, good and evil.”

Composer Guillaume expertly depicts the pressing frustration of the text by setting it in the key of D minor and rapidly shifting meter that eventually settles into a long series of measures in 3/4 time. Even though the time signature is familiar, Guillaume’s rhythmic scheme is both intentionally unnerving and completely fresh. To this unsettlement, the composer adds occasional complexity with faster rhythmic lines and unexpected harmonies. These additional intricacies are well-timed, he allows the music to settle for a brief period before he adds them. (Example 18)

Example 18, ‘Gagòt,’ m. 40-43.

At about the halfway time-point in the composer’s setting of Gagòt, Guillaume provides the solution to life’s frustrations with a beautiful chorale that sets comforting wisdom in contrast to the storm and stress of the opening measures:

“Life before death is a battle of every instant that cannot be won but one moment at a time. After the night, comes the day. After the rain, the sun rises. After messes, after mess . . . the heart settles. It’s striving in suffering that brings redemption. Ah! So be it.”

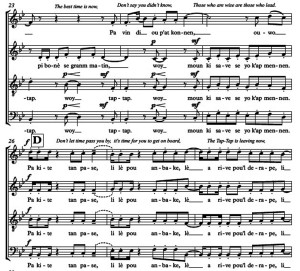

The Guillaume Gagòt is a beautiful collaboration of father and son as well as a superb example of an expert rendering of text painting in choral music. Composer Guillaume sets a similar text in Tap-Tap, although this Haitian Creole poem is by Louis Marie Celestin.

Guillaume’s Tap-Tap is a hot mess of layered syncopation punctuated with descending chromatic lines, repeated sixteenth notes, and occasional wails of delight. The encouraging text of the poem exhorts the listener to hurry and take advantage of the opportunity to do something for the nation and to accomplish something for society. There is an urgency to the music; it starts simply but increases in complexity at a fairly rapid rate. Although the majority of the work is driving syncopation, there are occasional moments of homophonic declamation.

Example 19, ‘Tap-Tap,’ m. 23-28.

Sydney Guillaume’s music is characterised by a high degree of rhythmic interest and his large body of work is well known in the United States. Those interested in the work presented here will also want to examine Kalinda, published by Walton Music, and Dominus Vobiscum, another father-son collaborative work commissioned by Seraphic Fire and also published by Walton Music. Both Gagòt and Tap-Tap are available directly from the composer’s website.

Edited by Shekela Wanyama, USA