A proud member of the International Federation for Choral Music for more than 30 years

Andrea Angelini, ICB Managing Editor, conductor and composer

Dear Anton, you have now been conducting the St. Olaf Choir for 30 years. How did you get in touch with them?

I was 16 when my pastor, Rev. Robert Hawk, told me that the St. Olaf Choir was performing at the Lincoln Centre in Manhattan. Knowing my love for excellent choral music, my pastor naturally assumed I’d be interested in this concert, but I had tickets to see the Moody Blues at Madison Square Garden.

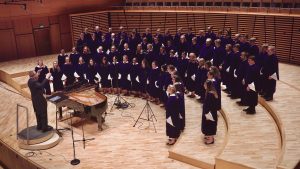

He wasn’t one to take no for an answer. Rev. Hawk went to my parents, and my mother vetoed the English rock band. The St. Olaf Choir put on a memorable choral concert, and the image of the iconic purple robes worn by the choir stayed with me.

A year and half later, I attended a Lutheran College fair on Long Island looking to strike out on my own and find a school far from New York. There were long lines of students waiting to talk to representatives of my top choice colleges. Growing up in New York has left me with a distaste for traffic, so when I passed—for the third time—a college booth with no line, I accepted an invitation by the admissions officer, Bruce Moe, to learn about St. Olaf College in Minnesota. I remembered the St. Olaf Choir and its purple robes. The college appeared to have everything I was looking for: an inclusive Lutheran tradition in which vocation was important, and a mission that incorporated a global perspective and fostered the development of the whole person in mind, body, and spirit. Its academics were excellent, and it had a strong religion department, a thriving music department, and great choirs.

But there was still one thing I wanted to know, “how many black students go to your school?”

Moe got a glint in his eye. “You’d make one more.”

I thought that was a really honest answer, and I put St. Olaf on my list of colleges to visit.

Can you tell us about your background? Where did you study music and why?

My parents, Esther and William Armstrong, supported my interest in music. They made extreme financial sacrifices for me to pursue my interest in music, including lessons, private schooling and being a member of the American Boychoir.

Carol and Carl Weber (graduates of Westminster Choir College) were the musicians at my home church who started a children’s church choir when I was in kindergarten. If it wasn’t for Carol, a major part of my musical journey would never have happened. She gave me my first solo when I was six years old – which I can still sing – and provided us with incredibly wise training. She also introduced me to the American Boychoir.

Singing in that choir lit my fire for choral singing. While there were only three or four African American boys in the choir at the time, we were treated equally and were valued for our talent and how hard we were willing to work. It was a transformative experience and established my standard for excellence in choral music.

Then of course came my time as a student at St. Olaf, where I learned from my predecessor,

Dr. Kenneth Jennings, and conductors Dr. Robert Scholz and Alice Larson. I still remember the first time I heard Alice conduct the St. Olaf Manitou Singers. I’d never heard women sing like that. It wasn’t this little girl sound; it was a rich, womanly sound. I remember witnessing the way that Kenneth Jennings would take his hands, and in an instant a phrase would just turn. Finally, there’s Bob Scholz, the most pastoral of my teachers, who cared deeply for the music he made, but even more for the human beings who created it.

I was also fortunate to be guided in my years of graduate study at the University of Illinois and Michigan State University by inspirational mentors such as Dr. Harold Decker, Dr. Charles Smith, and Ms. Ethel Armeling. Perhaps the greatest gift of my Illinois years was meeting my dear friend and colleague of nearly 42 years, Dr. André Thomas.

Conducting a choir, especially at as high level as you do, includes not only knowing the technique, but it’s also necessary at times to be a life tutor, a friend, a psychologist. What advice do you give to young conductors who want to start a career in this field?

As a young conductor, I tried to create a perfect choral performance. Throughout the years, however, I have learned that perfection is impossible. Instead, I seek excellence as we share our voices together in communal song.

As an adult, a person whose influence has steered my life professionally is Helen Kemp, professor emerita of voice and church music at Westminster Choir College. Her mantra, “Body, mind, spirit, and voice – it takes the whole person to sing and rejoice” has stayed with me for more than 40 years. I credit her with shaping my calling as a vocal music educator and conductor.

For young conductors, emphasis should not be placed on the subject, it has to be on the person. We use music as a means of grace to reach the inner soul of those we have the duty and delight to lead in our choral ensembles.

Do you think that choral music can be not only a form of art, but also a way to find something greater than us, whether you call him God, interior peace or something else?

For me, the art of choral music is an expression and praise of thanksgiving for God, or whatever people call that infinite being.

Throughout my career, music of the church – sacred music – has been the vast majority of the music I’ve performed with choral groups. Part of my roots growing up as an African American in the United States were developing a faith in God, care of neighbour, and care of creation. Also, a desire to serve in the world while not expecting that you were owed something in return. Finally, faith in a God that would walk with you through whatever challenges you face in life.

Throughout my years as a conductor, that experience has guided me as I’ve tried opening the world of the infinite creator to people of all ages. I realize there are many ways to experience that infinite creator, and for me, that God. I often feel closest to God while singing or conducting choral music.

Speaking about choral repertoire, to which repertoire do you feel closest?

A large part of my work as both a singer and conductor has been rooted in the Western choral canon of Europe and North America. Consequently, music of the church has been a strong component of that, but I’ve also explored secular music.

I’m also drawn to folk music from throughout the world, especially the negro spiritual. The negro spiritual speaks about the human condition – of pain and pleasure, joy and sorrow, and triumph over the worst indignities that can be put upon another human being. These elements are what’s made this genre of choral music so beloved throughout the world, and why I have especially enjoyed sharing it throughout my international conducting engagements.

In a previous edition of ICB, there was a discussion about ‘the culture of a conductor’. To explain this thought better, having culture is not only having perused many books or listened to many choral pieces, but being part of these ‘webs of significance’. Now, we cannot deny that the bulk of the repertoire of choral music comes from western music. It would be unfair to hide this kind of self-evident truth. Some say that many conductors, because of their place of birth and cultural upbringing, are not and never will be part of this kind of tradition in the deepest sense. Do you think that any choir, no matter their cultural and geographical origins, can perform any kind of choral music?

Your question raises an issue that is currently on the minds of many vocal music educators in the 21st century, namely one of cultural appropriation. I don’t think you must be of a certain race or culture to do music of a certain race or culture. However, I do believe as we are rigorously trained to understand and perform music of Western choral cannon, those same aspects of study and performance practice must be applied to music outside of one’s own culture.

Conductors must take the time to study the culture of a piece, aspects of its performance and music style, the use of language and dialect, in order to pay proper homage to the people from which this music emanates. If this is done well, I believe music can be performed from outside one’s own culture.

The International Federation for Choral Music (IFCM) is a world choral network. In your opinion, what should be its main goals and tasks?

I have been a proud member of the International Federation for Choral Music for more than 30 years and have had the opportunity to attend every World Symposium on Choral Music since the original in Vienna in 1987. I was sorely disappointed the 2020 Symposium in New Zealand was cancelled due to COVID-19.

IFCM is an important bridge to build relationships between choral communities from across the globe. At the symposiums I have been a delegate, lecturer, masterclass instructor, and choir conductor. These gatherings have been some of the most important events organized by IFCM, providing invaluable networking and exposure to choral music from around the world.

I also value the continuing research of IFCM and its work in developing nations. In the more recent years, its ability to bring people together through the internet has been crucial to developing communal song throughout the world.

You travel a lot as guest conductor and clinician. Where do you feel at home? Which foreign country is closest to your habits and your ideas about the performance and practice of the repertoire you conduct? And why?

My international experiences have helped me learn that our work can help build bridges and heal wounds. The songs we sing from different parts of the world are often the way we enter a cultural experience very different from our own. If we can treat that music with respect and do our best to understand how and why that music originated, we start to understand the people who created it, and we find a commonality in how we exist together. Once we begin singing together, our differences of gender, age, race, ethnicity, nationality, religious expression or not, sexual orientation, and socio-economic standing don’t disappear, but instead cease to become barriers.

I must admit that wherever I’ve travelled in the world, I’ve felt welcome. This has only strengthened my opinion that when we sing together, we break down the barriers that can divide us. I’ve spent a great deal of time in Norway and South Korea, and both of the countries have become like second homes to me. Through the gift of choral music, I’ve made friends throughout the world, and this has been one of the great blessings of being a conductor.

Anton, I would like to ask you a question as an ‘Italian director’. Italy, especially Rome and Venice, are considered the cradle of Renaissance polyphony. Why is this music, even in the 21st Century, still so admired and performed?

The music of the Renaissance is noted for the beauty and independence of the vocal musical line. This music also affords the singer and the listener to create beautiful harmonies. There is also a close interweaving between the text and music of these pieces that captures emotions of the human soul. That intersection touches us at the very core of our being.

Going back to the St. Olaf Choir, what are your next projects with them?

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned our world and any plans I’ve had for the St. Olaf Choir upside down. We certainly are facing a new paradigm shift in how we’ll even exist as the St. Olaf Choir in the near future. However, I hope that, despite this pandemic, our future aspirations will come to fruition.

One great dream of mine is to bring the choir to Africa. I’m also eager to resume projects with several of the wonderful music organizations here in Minnesota, including the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, VocalEssence, Magnum Chorum, and more.

Finally, as I look ahead at my final years as conductor of the St. Olaf Choir, I consider the possibility of new recording projects, in whatever forms that might take place. I also want to explore more the role of choral music as an advocate for social justice in the world!

Life is also made of dreams, some of them are probably impossible to fulfil. If you had a special power, what would you do to make the world better through choral music?

This might be an idealistic aspiration, but if I had the power to do so, it would be that all people throughout the world be encouraged to use their God-given skills of singing. The voice is the most human of instruments. Through it, we find common ground between people, share each other’s songs and lives, and find a common path of humanity.

This has been clear to me during the 23 years I’ve been part of the Oregon Bach Festival. Through this 50-year-old festival, founders Helmuth Rilling and Royce Saltzman have vividly showcased how people throughout the globe can make music with each other, come together, build bridges, and create enriching, life-long relationships through the art of choral music.

Finally, if you were not at St. Olaf, what else would you be doing and where?

I started my career at Calvin College (now Calvin University), conducting choirs at the institution and within the community. More than most people might understand, it was a very difficult decision to leave there when I assumed my current role at St. Olaf in 1990.

However, I feel a vocation, a vocāre, to St. Olaf.

The college is not perfect, but it is a place where people come to study, work, and strive to have a place of belonging. We live in a world that is so divided, where people are so quick to find the things that separate us. One of the great things about working in music – especially choral music – is that we can all find a place of belonging and a place where we can express ourselves and find community with those around us.

Also, St. Olaf has been a community that has aspired to nurture and lift up “servant leaders” in whatever our calling in life may be. For me, this sense of calling – “vocare” has been powerfully carried out as a member of the St. Olaf College community and especially through the work and mission of the St. Olaf Choir.

Edited by Mirella Biagi, UK/Italy