Giovanni Battista Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater: A Logogenetic Analysis[1]

Oscar Escalada, composer, arranger, musical director and musicologist

The term logogenesis describes the way composers use their knowledge of music to illustrate a written text. The word originates from the Greek logos, meaning ‘word’ and génesis, meaning ‘origin’.

In linguistic terms logogenesis is one of three strands of semogenesis; the other two being ontogenesis and filogenesis. However, we should not be confused by this because the significance that we give to this term in relation to musical analysis has nothing to do with systemic functional linguistics. As far as music is concerned, the word logogenesis is used to describe a procedure used from time immemorial to relate music to the written word. In the 16th century, Gioseffo Zarlino described this process as “mettere le parole in musica” (setting words to music).

The Stabat Mater is a medieval liturgical sequence attributed to various authors, the most likely of whom are Innocent III (c.1216) and Jacopone da Todi (1230-1306). Jacopone was adjudged to be the author of the Stabat by Georgius Stella, Chancellor of Genoa, in his Annales Genuenses, about a 14th century manuscript containing Jacopone’s poems.

Jacopone is known for his ‘laude’. These were songs in praise of the Lord originating from Saint Francis of Assisi at the beginning of the 13th century. He sang the ‘laude’ in his native language so that the Gospels could be understood by ordinary people who could not speak Latin. In the same way, Jacopone composed his poems in the Umbrian dialect and this is why there is some doubt about his authorship of the Stabat Mater, because it is in Latin.

This sequence was incorporated into the Christian liturgy in 1727 as the last of the five official sequences of the Catholic Church. The earlier ones, established by the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563, are Lauda sion by Wipo, Victimae paschali laudes, attributed to Innocent III, Dies Irae by St. Thomas Aquinas and Veni Sancte Spiritu by Tomás Celano.

The Stabat Mater has two texts that are somewhat different from each other. They are known as Dolorosa and Speciosa. The one that is used nowadays is the Dolorosa. The differences between the two can be seen right from the beginning:

|

Dolorosa Stabat Mater dolorosa Juxta crucem lacrimosa Dum pendebat filius |

Speciosa Stabat Mater speciosa Juxta foenum gaudiosa Dum jacebat filius |

One edition of Jacopone’s Italian poems, published in Brescia in 1495, includes both versions of the Stabat Mater but the Speciosa fell into disuse until 1852 when A.F. Ozanam discovered it in the National Library in Paris and re-transcribed it. He attributed both manuscripts to Jacopone and confessed that he had given up trying to translate Speciosa in verse form in favour of presenting both hymns in prose, because of the untranslatable charm of the original language, its musicality and its old-fashioned beauty.

Nevertheless, there are different views about the authorship of the Stabat Mater. While the Anglican hymnologist, Dr. J.M. Neale, attributed the authorship of Speciosa to Jacopone when he translated it into English in 1866, Phillipe Schaff, in his book Literature and Poetry, disagrees, arguing that it is unlikely that a poet would have written a parody of his own poem.

There is a great deal of literature about both hymns. However, both Protestants and Roman Catholics share a deep admiration for its pathos, its vivid descriptions and its devotional gentleness and piety.

Various versions of Stabat Mater Dolorosa have been compiled by Hvander Velden.

There are differences in the texts in some of the numbered sections as we can see below:

1 Stabat Mater dolorosa iuxta crucem lacrimosa dum pendebat Filius

2 Cuius animam gementem contristatem et dolentem pertransivit gladius

3 O quam tristis et afflicta fuit illa benedicta Mater Unigeniti

4 a) Quae moerebat el dolebat et tremebat cum videbat nati poenas incliti

b) Quae moerebat et dolebat Pia Mater dum videbat nati poenas incliti

5 Quis est homo qui non fleret Matri Christi si videret in tanto supplicio?

6 Quis non posset contristari Matrem Christi contemplari dolentum cum filio?

7 Pro peccatis suae gentis vidit Iesum in tormentis et flagellis subditum

8 Vidit suum dulcem natum moriendo desolatum dum emisit spiritum

9 Eia Mater, fons amoris, me sentire vim doloris fac ut tecum lugeam

10 Fac ut ardeat cor meum in amando Christum Deum ut sibi complaceam

11 Sancta Mater, istud agas crucifixi fige plagas cordi meo valide

12 Tui nati vulnerati tam dignati pro me pati poenas mecum divide

13 a) Fac me vere tecum flere crucifixo condolere donec ego vixero

b) Fac me tecum pie flere crucifixo condolere donec ego vixero

14 a) Iuxta crucem tecum stare te libenter sociare in planctu desidero

b) Iuxta crucem tecum stare et me tibi sociare in planctu desidero

15 Virgo virginum praeclara mihi iam non sis amara fac me tecum plangere

16 a) Fac ut portem Christi mortem passionis eius sortem et plagas recolere

b) Fac ut portem Christi mortem passionis fac consortem et plagas recolere

17 a) Fac me plagis vulnerari cruce hac inebriari ob amorem filii

b) Fac me plagis vulnerari fac me cruce inebriari et cruore filii

18 a) Inflammatus et accensus, per te, Virgo, sim defensus in die iudicii

b) Flammis ne urar succensus, per te, Virgo, sim defensus in die iudicii

c) Flammis orci ne succendar, per te, Virgo, fac, defendar in die iudicii

19 Fac me cruce custodiri morte Christi praemuniri confoveri gratia

20 Quando corpus morietur fac ut animae donetur paradisi gloria. Amen

The Dolorosa and Giovanni

The Stabat Mater cannot be fully understood just by examining it as a sublime work of art in the history of music. The composition by the most highly regarded composer in the city was usually performed at the annual feast day of Our Lady of Sorrows (el Dolor de la Virgen), which took place on the Friday before Palm Sunday. The procession slowly wound its way through the streets of Naples and it is there, in the open air, and with all the background noises of the city, that we can imagine the performance that, nowadays, would normally be performed as a concert work in the enclosed environment of the concert hall. As was usual in popular celebrations in Naples, the singing and playing of the professionals was mixed with other singers, instrumentalists and ritualistic dances such as the tarantella (typically associated with the rites of exorcism), forming simple improvised harmonies around the melodies of the Stabat Mater.

Pergolesi was born in 1710 and died very early of tuberculosis in 1736, in the Capuchin monastery at Pozzuoli. He was only 26 years old. He was originally from Jesi, but at a very early age he went to Naples to study violin and composition in the Conservatory “dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo”. He became Deputy Choir Master in Naples in 1734 and Supernumerary Organist of the royal chapel in 1735.

His popularity and the high regard in which he was held in Naples stem precisely from the fact that he was interested in composing works in the language understood by the common people: the Neapolitan dialect. During his short life, he composed various operas which have now been largely forgotten specifically because they were written in this dialect. The first of these was Salustio. In 1731 he composed La Conversione di Guglielmo d’Aquitania and the following year Lo Frate’nnamorato. Later, in 1734, he composed Adriano in Siria and in 1735, Il Fluminio, another comedy written in dialect.

Pergolesi is considered together with Baldassare Galuppi, Giovanni Paisello and Domenico Cimarosa, as one of the great 18th century composers of opera buffa (comic opera). His best-known opera is without doubt La serva padrona, composed in Italian and premiered in 1733.

The Stabat Mater was his last work, composed in 1736 shortly before his death. When this sequence was incorporated into the Christian liturgy, Pergolesi was 17 years old. It had a great impact during that time and also on Pergolesi himself because the four accepted sequences in the Christian liturgy had not been changed for more than 160 years. He was commissioned to compose his Stabat Mater by the same Order of Naples for whom Alessandro Scarlatti had composed his version of the work twenty years earlier.

Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater had a huge effect on other composers of that time such as Johann Adam Hüler (1728-1804) and Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1860). Even Johann Sebastian Bach showed his admiration in his cantata ‘Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden’ (Psalm 51).

The Text and the Music

There is no doubt that as Pergolesi was fundamentally a composer of opera, and in particular of opera buffa, a close relationship between text and music was inevitable. Thus it is by no means unusual to discover certain musical features in his Stabat Mater which allow us to identify the importance he gave to the text, making subtle use of logogenesis.

Throughout the work so many musical phrases correspond so completely to the text, and at times to individual words, that this could not possibly be a coincidence.

In the first place, it is important to bear in mind that the Teatro Sacro Italiano had its origins in Jacopone’s ‘laude’ and that Pergolesi was fundamentally a composer of opera. There would be a similarity between the two authors based on the tendency of both to develop the dramatic and theatrical aspects of their work.

A brief analysis of the Dolorosa shows that its general structure is in two sections. The first describes the pain of the Mother of Christ on seeing her son crucified and suffering for the sins of the people, while the second is a prayer to the Mother of Jesus, to share her suffering and thus please her son.

It is clear that this structure did not go unnoticed by Pergolesi because his Stabat Mater is also divided into two sections corresponding to the text. Both sections have six parts; the first goes from Number 1 (Stabat Mater dolorosa) to Number 6 (Vidit suum) and the second from Number 7 (Eia Mater) to Number 12 (Quando corpus morietur).

To make this structure possible, Pergolesi had to use more than one verse in some numbered sections because there are twenty verses in all. Thus, he put two verses into Number 5, and five verses into Number 9. He used two verses each in Numbers 10 and 11. In the rest he put one verse in each numbered section.

Let us look at the text translated into English prose:

|

First section: descriptive |

|

Juxta Crucem lacrimosa Dum pendebat Filius |

The grieving Mother stood weeping by the cross where her son hung crucified. |

|

2. Cujus animam gementem Contristatam et dolentem, Pertransivit gladius |

Her grieving soul, compassionate and suffering, was pierced by a sword. |

|

3. O quam tristis et afflicta Fuit illa benedicta Mater Unigeniti! |

Oh how sad and afflicted was the Blessed Mother of her only-begotten son. |

|

4. Quam maerebat, et dolebat Pia Mater, dum videbat Nati penas incliti |

The pious Mother mourned and grieved to see her son’s terrible suffering. |

|

5. Quis est homo qui non fleret Matrem Christi si videret In tanto supplico? Pro peccatis suae gentis Vidit Jesum in tormentis, Et flagellis subditum. |

Where is he who would not weep on seeing the Mother of Christ in such great torment? She saw Jesus in torment, scourged for the sins of his people. |

|

6. Vidit suum dulcem natum Moriendo desolatum, Dum emisit spiritum. |

She saw her sweet son dying, forsaken, giving up his spirit. |

|

Second section: prayer

|

|

|

7. Eia Mate, fons amoris, Me sentire vim doloris Fac, ut tecum lugeam. |

Oh Mother, source of love, let me feel your pain so that I may grieve with you. |

|

8. Fac ut ardeat cor meum In amando Christum Deum Ut sibi complaceam. |

Grant that my heart may burn in the love of Christ Jesus, that I may please Him. |

|

9. Sancta Mater, istud agas, Crucifixi fige plagas Cordi meo valide Tui nati vulnerati Tam dignati pro me pati, Poenas mecum divide. Fac me tecum pie fiere, Crucifixo condolere, Donec ego vixero. Juxta crucem tecum stare, Et me tibi sociare In planctu desidero. Virgo virginum praeclara Mihi jam non sis amara Fac me tecum plangere. |

Holy Mother, grant my prayer: imprint the wounds of the crucified one deeply on my heart. Let me share the pain that your wounded Son deigned to suffer for me. Let me weep with you and share the suffering of the crucified one, all the days of my life. Let me stand beside the cross with you and join you in your weeping. Virgin, the most exalted of all virgins, do not be bitter with me: let me weep with you. |

|

10. Fac ut portem Christi mortem, Passionis fac consortem, Et plagas recolere. Fac me plagis vulnerari, Fac me cruce inebriari, Et cruore filii. |

Grant that I may bear the death of Christ, share his Passion and remember his wounds. Let me be wounded with his wounds, let me be enraptured by the cross and the blood of your Son. |

|

11. Inflammatus et accensus, Per te, Virgo, sim defensus, In die judicii. Christe, cum sit hinc exire, Da per Matrem me venire Ad palmam victoriae. |

Oh virgin, save me from the flames and defend me on the Day of Judgement. Christ when I must leave this life, grant that through your mother I may gain the palm of victory. |

|

12. Quando corpus morietur Fac ut animae donetur Paradisi Gloria. Amen. |

And when my earthly body dies, may my soul be granted the glory of Paradise. Amen |

The numbered sections above match the way Pergolesi divided up the text. Notice that there are 12 numbers and there were 12 disciples. The text in italics corresponds with the numbering of each sequence.

A discussion about the way that Pergolesi put his own stamp on the interpretation of the poem is unavoidable at this level of analysis. It was not a capricious decision to allocate certain verses to the numbered sections. Thus, for example, those used in Number 9 cover the same theme and the whole section covers the same literary content.

He uses similar criteria for the selection of the two verses of Number 12.

This first step is of tremendous importance for understanding what is being said. The fact that the shape of the music matches that of the text enables the content to be expressed with greater clarity and without distortion.

Some Logogenetic Considerations

Without wishing to make a very detailed study of the logogenesis techniques used by Pergolesi, I would like, in this chapter, to illustrate this theme by giving some examples taken from the first section of the piece.

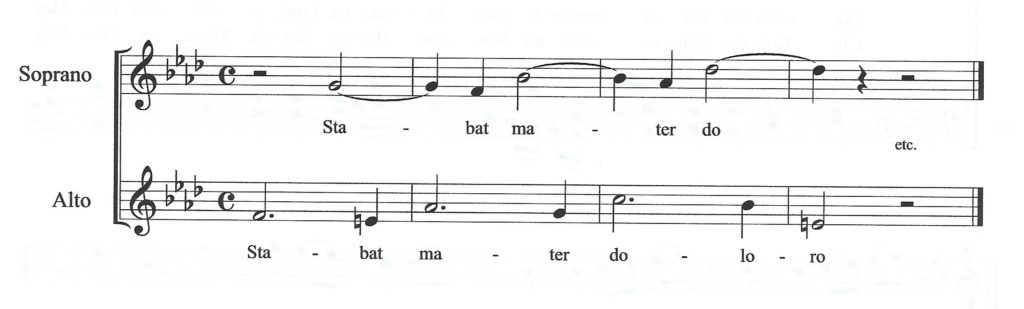

From the beginning of the work, Pergolesi effectively sets the musical mood for the Stabat Mater as one of profound sadness by using successive dissonances, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

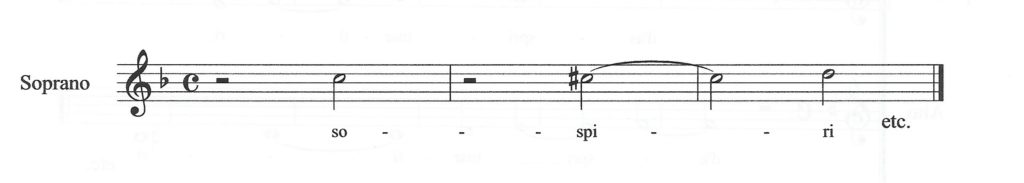

This technique had been used before, more than a century earlier, by Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa with the words ‘ásperos martirios’ (bitter torments) in his madrigal Itene o miei sospiri (Fig 2).

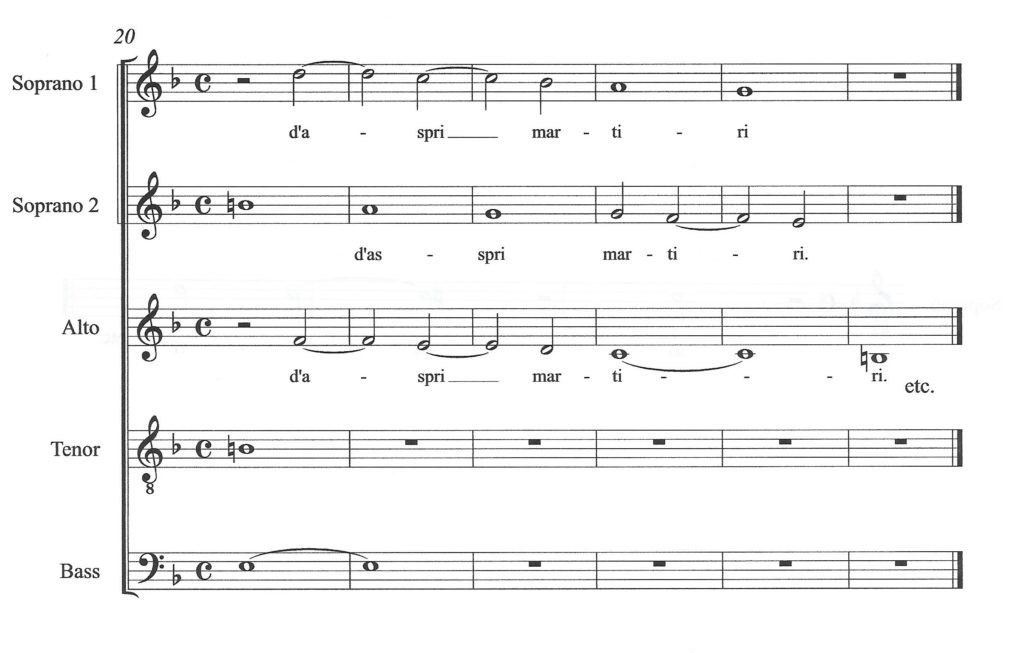

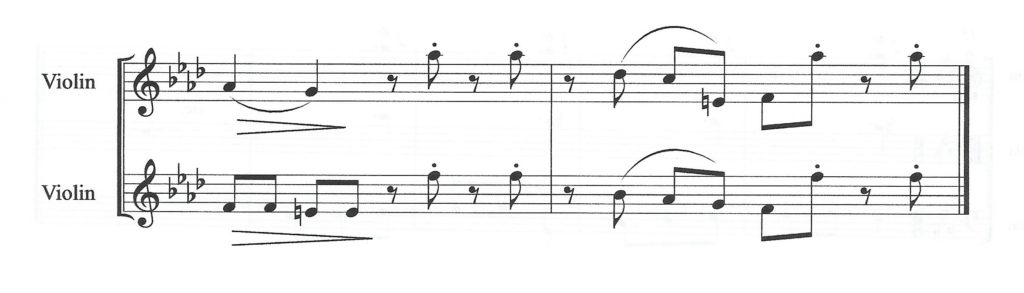

Pergolesi also emphasised this notion of grief with the insertion in bar 8, violins I and II, of rests to separate the quavers giving the effect of sighing. This technique had also been used before by Gesualdo in the madrigal mentioned above (Figs 3 and 3.1).

In Number 2, the chords anticipate the text referring to the sword which pierced her suffering soul, in bars 15-18 (Fig.4).

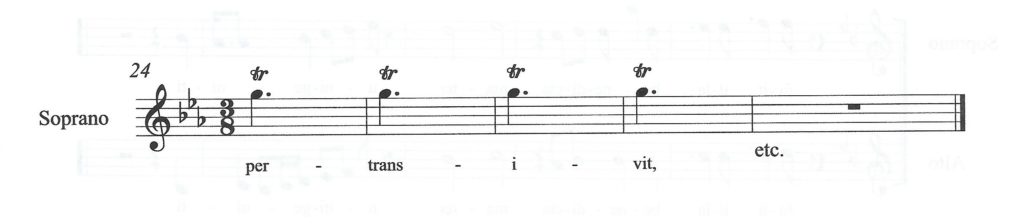

Much later, following on from bars 77 and 99, he makes use of the same effects for the text pertransivit gladius (a sword pierced), with the high notes in the soprano line mirroring the pain of the sword’s thrust (Fig. 5).

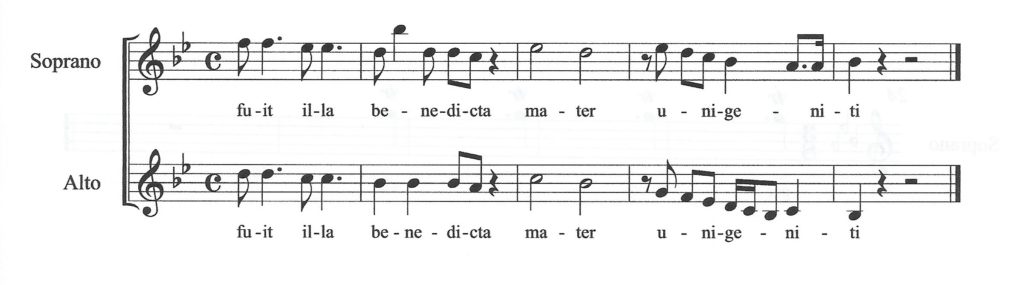

In Number 3, the only word that is given minims is the word Mater, which in terms of interpretation allows emphasis to be placed on the feeling of pity towards this grief-stricken and afflicted woman faced with her only son dying on the cross (Fig. 6).

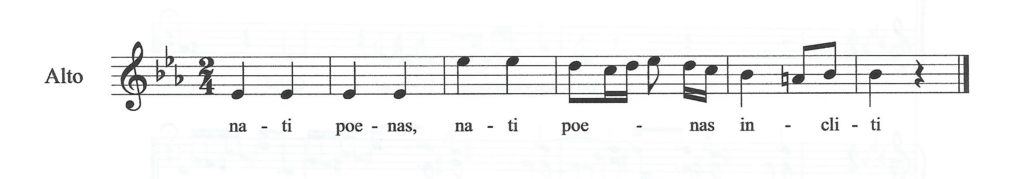

In Number 4, he uses the octave interval in the melody, de nati poenas, following on from bars 43 and 53, to illustrate her cry of pain at her son’s ‘terrible suffering’(Fig. 7).

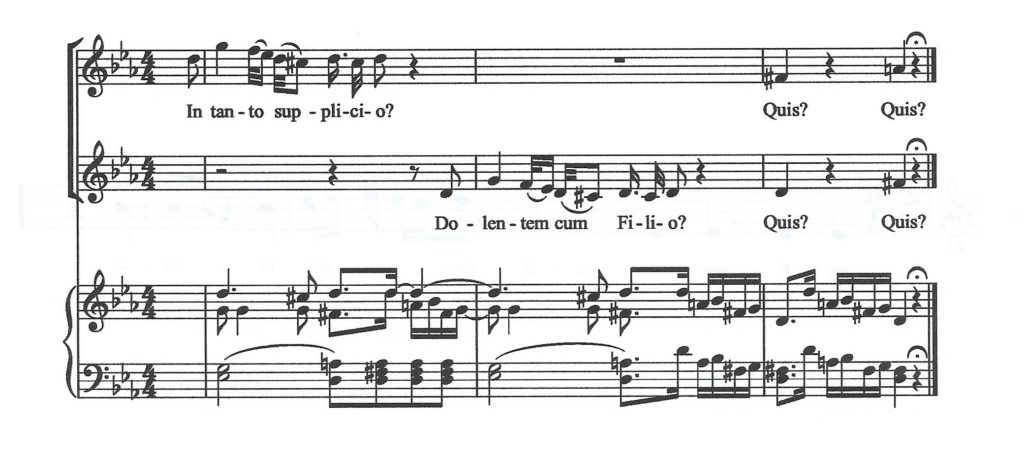

In Number 5, the words in tanto and dolente are interpreted by long notes and the phrase culminates with the descending melody of tanto suplicio which ends in the dominant major key. The following phrase, Quis non posset contristari, is developed in the same dominant form but this time in the minor key. The section concludes with the question quis? (who?), on repeated crotchets on the first and third beats, separated by rests. This repeats a formula which Pergolesi had already used in Number 1, but this time he uses it to create great tension around the question (Fig. 8).

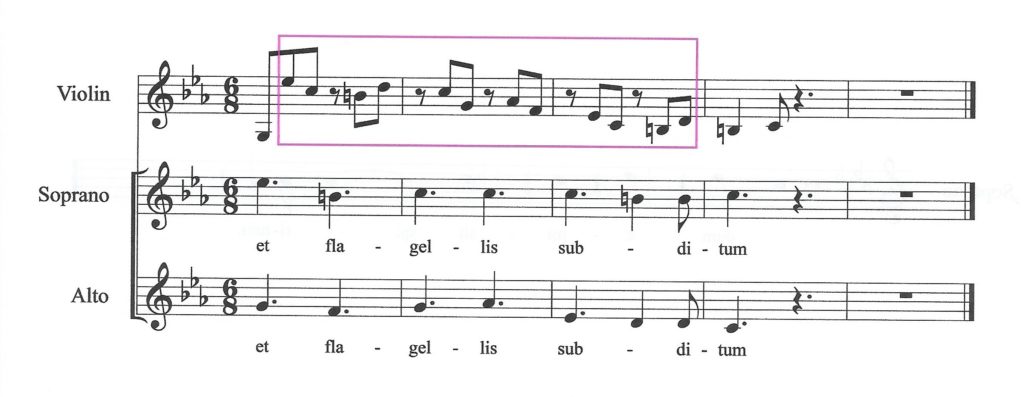

In the second part of this numbered section he stresses the word flagellis (whips) (Fig. 9). Notice in the violin part the pattern of quavers in an acephalous rhythm over this word, to mirror the action of the whips.

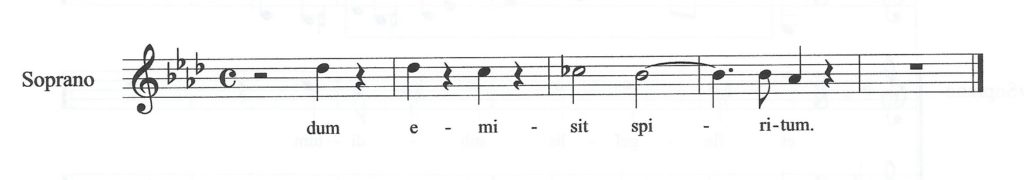

In Number 6, (Vidit suum), the last of this descriptive first section, Pergolesi stresses the phrase dum emisit spiritum (giving up his spirit). Here he goes back to the technique of using notes interspersed with rests to create the effect of the soul leaving the body (Fig. 10).

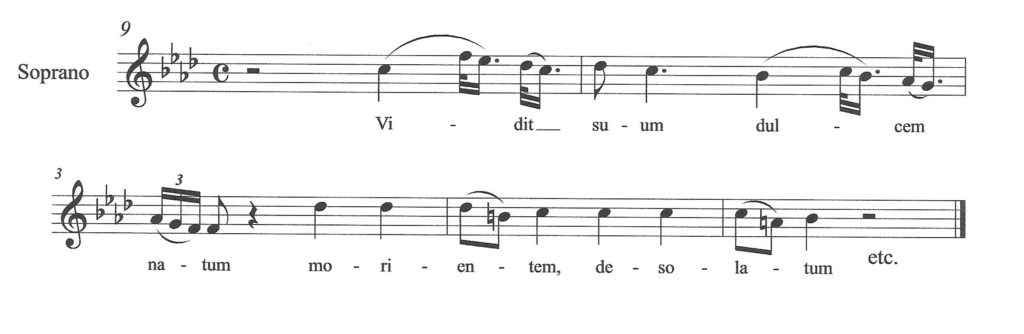

However, the most interesting relationship between music and text in this section is demonstrated by the contrast between the two phrases Vidit suum dulcem natum and morientem, desolatum. There is a marked difference between the melody that begins with an interval of a fourth followed by a strictly dotted rhythm over the first phrase (she saw her sweet son) and the following, more static section, where Pergolesi uses a pattern of crotchets and quavers in a descending melody to illustrate the words ‘dying, forsaken’ (Fig. 11).

This is a technique that was also used by Bach.

[1] This article is taken from a chapter of the book, Oscar Escalada, Logogénesis, Barry Editorial, Buenos Aires, 2012

Bibliography

Jack Vincent and Danny Baker, Bourbon Street Black , Oxford University Press, New York, 1973

Ferdinand de Sausuure

César Evaristo, 100 tangos de oro, Ediciones Lea Libros, Buenos Aires 2006

L. Ceccarelli, Prosodia y métrica del latín clásico, trad. R. Carande, Sevilla 1999

Rodney Williamson, Reflexiones sobre la compleja relación entre ideología y género discursivo, Universidad de Ottawa, Canadá

Alfredo A. Camus, Curso elemental de Retórica y poética, Madrid, 1847

Paroissien Romain, La messe et l’office, Chant Gregorien extrit de l’édition Vaticane et transcription musicale des Bénédictins des Solesmes, Société Saint Jean L’Évangéliste, Paris, Tournai, Rome, 1948

Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2008.

Glenn Watkins, Preface to Igor Stravinsky, Gesualdo. The man and his music, Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, 1977

Cecil Gray, Philip Heseltine, Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, Musician and murderer, K.Paul, Trench, Truber & Co., 1926

Albert Sweitzer, Bach, el músico poeta, Ed. Ricordi

La Opera – Enciclopedia del arte lírico, Aguilar, Madrid 1979

Arnold Hauser, Historia del arte y la literatura, Fondo de cultura economica

Juan Straubinger, Mons. Dr.,, LA SANTA BIBLIA, Traducción Fundación Santa Ana, La Plata 2001

(1) Melamed, Daniel R. – J.S. Bach and the German motet. Cambridge University Press. UK, 1995

Okon Edet Uya, Historia de la esclavitud negra en las Américas y el Caribe, Ed. Claridad, Bs. As., 1989

Flora Davis, La comunicación no verbal, Alianza Editorial, España, 1998

Translated from Spanish by Mary Coffield, U.K.

Edited by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy