By Freddy Miranda, Percussionist and Teacher

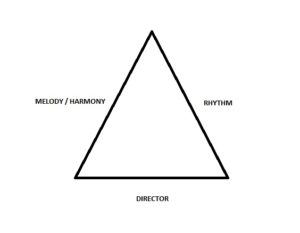

One of the most notable recent developments in Latin American choral music is an emphasis on instrumentation. Recall that, during the 1950’s, choral music was mostly a cappella; the sounds of folk and popular instruments were present only insofar as they were imitated by voices. In the 1970’s, however, there came an obvious change: a new Latin American choral sound emerged, thanks to the addition of various rhythmic and harmonic instruments that blended perfectly with the human voice. The appearance of a wide variety of percussion instruments supported the chorus musically, while providing on-stage independence and presence. The inclusion of rhythmic elements (percussion instruments) also offered directors more resources and artistic possibilities, which in turn created an interdependence between the rhythm, the harmony/melody, and the director. These relationships create an indivisible unity, which can be expressed graphically as in the figure below:

In more than two decades as a percussionist accompanying choirs and 15 years as a teacher, I have had to teach my students and disciples to channel the intricacies of each musical style. In rock, jazz, salsa and other styles of music, the instruments all compete with one another, striving to stand out within the musical texture. In choral music, the fundamental role of the instruments lies instead with the choir, and our function as percussionists is to accompany the ensemble. Each elements of the set should know its role. Percussion instruments offer a rhythmic base and thus maintain the tempo and accents typical of each style, whether it be ethnic, popular or any other style of Latin American music.

Latin American musical styles are very diverse, and it is imperative to study each in depth to discover the “malice” (identity, particular nature) contained within. For example playing a Colombian cumbia is not the same as playing a Panamanian cumbia, even though the instruments used are the same. Each one has a distinct “malice”, which makes it sound a particular way. Hence, rather than teach my students to play a particular rhythm on a specific instrument, I encourage them to deepen their knowledge of many styles, as well as to explore and discover more about the codes and signals that are translated into sounds, which in turn will allow them to communicate the intended message.

I talk about my students because I realize the potential of every young choral singer to become a percussionist able to accompany a choral ensemble. Regardless of age, choral musicians have a simple and dynamic understanding (sometimes instinctive) of the possibilities of each style. This knowledge becomes the foundation that provides a viable link between the choir and the accompanying instruments. It should be pointed out that this phenomenon is not restricted to the geographic regions of Latin America and the Caribbean: those rhythms have been masterfully executed in non-Latin countries as well, and the inclusion of these instruments has produced excellent results throughout the choral world.

Once the musicians involved (director, choir members, and especially the percussionists) get to know the fundamentals of every musical genre (including knowledge of the accessory instruments such as keys, guiro, cowbell, bells, maracas, or shequerés) they need to investigate further the instruments used to créate a particular genre’s rhythm or style such as conga drums, timbales, or bongos. In short, it is necessary to know the percussion characteristic of each rhythm family. This creates an appropriate accompaniment for each piece, and, moreover, teaches students confidence and independence on each percussion instrument. Thus, the new generation of accomplished percussionists acquires the psychomotor development needed to improve their ability to make music with each instrument. To teach students these rhythms, it is appropriate to use spoken phrases, letters, words, and idioms of everyday life that are rhythmically simple, yet easy to retain in our memory. These have a rhythmic cadence that in many cases is transferable to the rhythmic formulas typical of folk and popular instrumentation.

I emphasize here that in all my workshops, I mention the importance of the drum as a means of expression and of transmission of messages. Each rhythm played on the drum goes beyond the simple written score, it carries the inspiration of each performer. In a youth chorus, each musician has the potential to express him or herself through a percussion instrument. My role is not only to accompany the choir, but to teach some choir members to accompany the choir percussion. In my experience I see that the pupil imitates his teacher, taking note of the teacher’s posture and the way he holds and plays each instrument. I supervise them directly in order to improve each run-through; they subsequently are able to incorporate those techniques fluently and automatically into the choral texture, and also to interact in the role of the accompanist. Thus, not only a theoretical approximation but a practical component is included in the learning process. Another important step is the teaching of the elements and tools proper to each rhythm (e.g. rhythmic notation, terminology and concepts); this will greatly facilitate the learning process.

Finally, each student must understand the construction of each rhythm and the nature of ensemble work. This is achieved in practice sessions or what I call the “instrument circle”, which consists of a minimum of 3 students sitting in a circle and asking each to play in turn a selected instrument for approximately one minute, without errors. It is important not to mix several instruments until each student has mastered the technique for each, as this could cause confusion. The students may choose to play different Latin American musical styles or decide to practice on the same one. They then move on to play several instruments simultaneously, thereby creating an ensemble. This teaching technique helps students master each style, which they can then combine with previously learned rhythms. Finally, they learn the most appropriate way to accompany chorales in each of the different styles. Everything is combined in a single dynamic, simple and not overly scholarly practice, since in my opinion, many scholastic techniques blocks learning. In many cases, students use other learning methods such as reading recommended articles, listening to recordings, attending concerts, and sometimes having direct interaction with professional performers. This long process concludes with a public demonstration, and ultimately, with what I call the “graduation,” which entails bringing these young percussionists together as a team of instrumental accompanists, with the teacher present to provide security and confidence.

During my career as a percussionist and teacher, I have observed that all students express music differently, regardless of age or the chorus in which the student participates. Their inclusion in the role of accompanying musicians helps form musical capabilities for understanding the complexities of Latin American music, keeps them involved in the daily events of their respective assemblies and encourages respect for the individuality of each performer. This musical knowledge will remain throughout their musical life, allowing them to become good percussionists and better singers. It stimulates young people in many ways, providing positive values of interaction, cooperation and teamwork; and who knows, could potentially generate excellent and versatile choral directors in the future.

Freddy Miranda, Venezuelan Percussionist, has been a part of popular and folk music groups, specializing in accompanying choirs. He is a consultant, workshop leader, and instructor of Venezuelan and Latin American percussion, and remains involved in the formation of choirs in schools and communities. Freddy is active in various groups such as the project “Building Singing” of the Foundation Schola Cantorum de Venezuela, the Latin American Choral Ensemble, the American Orquestina and Traditional Instruments Anakarinarote, and performs as a percussionist in Venezuela and abroad.

Freddy Miranda, Venezuelan Percussionist, has been a part of popular and folk music groups, specializing in accompanying choirs. He is a consultant, workshop leader, and instructor of Venezuelan and Latin American percussion, and remains involved in the formation of choirs in schools and communities. Freddy is active in various groups such as the project “Building Singing” of the Foundation Schola Cantorum de Venezuela, the Latin American Choral Ensemble, the American Orquestina and Traditional Instruments Anakarinarote, and performs as a percussionist in Venezuela and abroad.

Edited from the French by Anita Shaperd (USA)