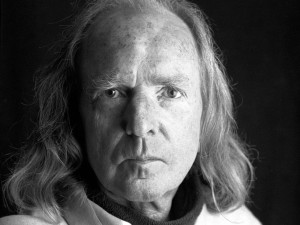

By Ivan Moody, composer, conductor and Orthodox priest

Sir John Tavener (1944-2013) was not only a composer of enormous versatility, but one who managed to surprise everybody with every new development in his stylistic trajectory. He himself hated the word “development”; he associated it with high modernism and arid intellectualism. He was much more interested in a search for sources, for origins; and it is really that obsession that links together all the phases of his compositional output. The very first time I met him he asked me what I thought about Tradition (you could hear the capital “T”), and we discussed this continually over the years.

It is this attempt to situate himself within Tradition that explains the fact that, looking back, one can find so many connections between the different phases of Tavener’s work. These are generally apparent through an aspiration towards ecstatic stillness, though this might be arrived at through violence – notably in his opera Thérèse (1973). This ecstasy was expressed principally through Tavener’s extraordinary melodic sense – which connects such early works as the vast cantata Últimos Ritos (1968) with Thérèse, and subsequently with Akhmatova Requiem (1980), The Protecting Veil (1988), Requiem (2007) and one of his last works, the Love Duet from Krishna (2012) – and the constant recourse to the high soprano voice.

The early works that brought Tavener fame, especially The Whale (1968) and Celtic Requiem (1969), worked almost on a comic-strip principle. Celtic Requiem is a vast collage, superimposing the Latin Requiem Mass, early Irish poetry and children’s games related to death rituals. The piece extinguishes itself, hauntingly, in a quotation of Cardinal Newman’s hymn Lead, kindly light, sung against itself in canon. Canon is another constant in the composer’s work; In Alium (1968) contains one in 28 parts, and there is a triple-choir canon in the yet-to-be-heard Requiem Fragments (2013).[1]

Últimos Ritos (1968-72) is far more austere, dealing with St John of the Cross’s mystical death unto oneself, but the lessons of the collage period were not lost, as is evident in the colourful, multilingual “Nomine Jesu” section, and layering is also apparent in Thérèse (1973). This dazzling, violent portrayal of the spiritual conditions through which St Thérèse of Lisieux passed as she lay dying was a critical failure when it was finally performed in 1979. Its composition had been paralleled by a crisis both musical and spiritual in Tavener’s life, a crisis solved by his meeting Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church in Britain, and his conversion to Orthodoxy in 1977.

The earliest works Tavener wrote after his conversion look both backwards and forwards, as the ‘cello concerto Kyklike Kinesis (1977) shows, in its saturated chromaticism and serial construction that nevertheless leaves room for a glimpse of ecstatic stillness in the Canticle of the Mother of God for solo soprano and choir that is incorporated into it. With the disastrous first performance at the Russian Cathedral in London of the Liturgy of St John Chrysostom (1977), Tavener realized that the traditions to which he has aspired until that point had been of his own making, and so he set about absorbing those of the spirituality and music of the Orthodox Church.

Akhmatova: Requiem (1979-80) symbolized the change, bringing with it a rich vein of lyricism even as it continued to make use or 12-note rows, and sets some of the most heart-wrenchingly desperate poetry ever written. The première in 1981 under Gennadi Rozhdesvensky was another critical failure, but the critics failed in this case to spot a genuine masterpiece. 1981 saw the composition of what still seems to me Tavener’s most uncompromisingly austere work, the unaccompanied Prayer for the World, setting the Jesus Prayer in rigorous mathematical fashion, written for the John Aldiss Choir, but the warmth of his new lyrical style became apparent in other works, notably Funeral Ikos (1982) and the astoundingly “stripped” Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete (1980), works brought about by his collaboration with The Tallis Scholars, whose repertoire had recently come to include mediaeval Russian Orthodox music.

This collaboration reached its apex in many ways with Ikon of Light (1983) for choir and string trio. Tavener’s melodic gifts are given free rein in the central movement, a setting of the Prayer to the Holy Spirit by St Symeon the New Theologian, surrounded by precisely calculated short movements setting single words. The subsequent flow of liturgical and paraliturgical compositions came to characterize the composer’s work for most people involved in the choral world, but paradoxically, the summit of this period, the monumental Vigil Service (1984), which was first performed liturgically at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. Unfortunately choirs have not generally found opportunities to sing excerpts from it, though the remarkable settings of Phos hilaron, the Nunc dimittis and the Great Doxology are amongst the finest unaccompanied choral music Tavener ever wrote. Other works from this period also deserve revival in concert, such as the austerely beautiful Eis Thanaton (1985), one of a number works in memory of the composer’s mother, and the monumental choral-orchestral Akathist of Thanksgiving (1987).

A combination of melodic beauty and ritualized structure underlies both the Akathist and The Protecting Veil (1988) for solo ‘cello and strings, whose success was as spectacular as it was unexpected. It opened the way for Mary of Egypt (1989), a chamber opera that Tavener preferred to describe as a “moving icon”, and two very large-scale works dealing with fundamental themes of Christian theology, The Apocalypse (1991) and Fall and Resurrection (1997).

By the time he wrote Lamentations and Praises (2000) for Chanticleer, Tavener had begun to take a more universalist approach, so that in Lament for Jerusalem (2000), he could employ elements from Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Other works drew more specifically from particular traditions, including Buddhism, Islam and Hinduism, but it was the combining of them – or rather, for Tavener, the search for the perennial source behind them – that characterized some of his most remarkable late work, most notably the seven-hour Veil of the Temple (2002) and the astoundingly beautiful Requiem (2008).

Tavener’s last works bring to mind many connections with his earlier music. The Death of Ivan Ilyich (2012), a monodrama to a text drawn from Tolstoy moving from the depths of despair to a radiant apotheosis, suggests The Immurement of Antigone (1978) and Akhmatova Requiem, while the Love Duet from Krishna (2013) for which Tavener himself invoked the example of Papageno and Papagena in The Magic Flute, strongly recalls the “Bless” duet from Mary of Egypt; and the deep chanting by the basses of “Om namo narayanara” suggests the chanting of the Jesus Prayer in Ikon of St Seraphim. It also seems, like the Requiem, to be connected with the English mystical tradition of Holst (particularly Savitri and The Hymn of Jesus) and John Foulds.

Shortly before his death, Tavener said, “The rapt and the austere are the two areas that I feel have inhabited, and the feminine, yes, the feminine, the eternal feminine.”[2] It would surely be impossible to find a better summation of his life’s work.

[1] See Peter Phillips’s comments at http://www.theartsdesk.com/classical-music/remembering-tavener and also at

http://www.spectator.co.uk/arts/music/9082101/remembering-my-friend-john-tavener/

[2] Interview with Tom Service in October 2013, initially available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03nc3qr