John D. Perkins

Though Arabic choral music has a long history in the Arab world, the non-Arab world is just beginning to engage with the genre.[1] I wish to open a discussion about the practical and philosophical nature of Arabic choral music, both as an introduction for choral musicians unfamiliar with the genre, and as a potential perspective for Arabic choral arrangers, alike. Such a discussion deserves follow-up and will hopefully inspire interest in the Arabic choral genre.

As an American conductor teaching Arab undergraduate students at the American University of Sharjah (United Arab Emirates), I believe in the power of Arabic choral music as a vehicle for a community-building dialogue between Arabs and non-Arabs, especially in the West. This dialogue exists on a daily basis in my interaction with both students and faculty, and has precedence in other realms of life. On a larger political scale, musical intervention relieved Arab-Israeli tension surrounding the signing of the 1994 Peace Accord.[2] “Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat…weren’t speaking. After hearing [a] song [performed by a choir of fifty Arab and fifty Israeli children] they signed a contract they hadn’t signed before. Perhaps it’s a bit naive to believe that music can influence the Peace Process, but I believe it,” recounts Dalal, the main soloist at the concert. Similarly, The State Concert Agency of Norway sponsored research on interethnic classrooms and how to change negative stereotypes of immigrants. The agency discovered that discussion of cultural differences did not amount to real change in their students, because it did not reach the students on an emotional level. Intercultural musical engagement, however, significantly impacted students in the study. “The idea was not primarily to present the music traditions…in their ‘pure’ form, but rather to stimulate participation in interethnic musical activities.”[3] The rich diaspora of Arabic melodies transmuted into choral arrangements may also be such a tool that could serve in generating a sense of cross-cultural tolerance in the post-9/11 era. Furthermore, choral audiences abound in significant numbers across the globe. Using the doorway of choral music, Arabic music has great potential to become a more common part of international musical vocabulary.

One of the discussions amongst arrangers is about stylistic treatment. Traditional Arabic music’s homophonic, or heterophonic, nature is mostly negated after setting it in a harmonic, choral style. Clearly, music of similar traditions that adopts a harmonic mantle has done more to enhance traditions than to denigrate them. But this question begs thoughtful response of how to treat the choral texture. What is ‘allowed’ or ‘not allowed’ in a choral arrangement may only be determined by the arranger; philosophical and social context, however, may influence practical considerations.[4]

For non-Arabs, a brief introduction to the style helps the process of engaging with Arabic choral music. The core of Arabic tonality is the maqam, the collection of Arabic scales. It contains scales familiar to the West as well as many others with microtones. The Arabic soloist demonstrates virtuosity by negotiating these maqammet (scales), in an ornamented, improvisational manner, which directly relates to text declamation. Generally, modern arrangers avoid harmonizing maqammet with microtones, due to issues of tuning harmonies.[5] Pieces containing ‘call and response’ between soloist and choir and mawwal[6] allow the soloist to demonstrate orrub (or ornamentation) and vocal expertise. These key, traditional values may occur in performances of Arabic choral music, but also require long-term guidance from, or more likely the direct involvement of, an expert. Such involvement is one of the most important ways to create positive bridges for ensembles and audiences alike.

Publication and performance contribute to cultural preservation. Gaber Asfour, a prominent Egyptian scholar, echoes a popular Arab sentiment that, “[globilization] has endangered the peculiarities of [Arab] national cultures, arousing the need for redefining identity in the context of globalization.”[7] As a result of musical globalization, popular Arabic music today often substitutes the sounds of acoustic instruments with digital sounds. Arabic musicians commonly express their concern that the demand for takt (Arabic instrumental groups) is quickly dwindling, as is the interest from the younger generation to learn this style on original instruments. Within the genre of Arabic choral music, however, the Arabic takt may integrate fluidly with a chorus. It provides a traditional soundscape, rhythmic modes (awzan), and a tonal context. The growth of Arab choral music may encourage those who wish to support the preservation of traditional Arabic musical values for future generations.

Music publishers, and indeed the entire Arab translating community, are developing helpful hybrid approaches toward Arabic transliteration. Latin letters and characters from the International Phonetic Alphabet provide a general guide to pronunciation. However, without help from a native speaker, the Arabic language is a linguistic challenge. Arabic pronunciation produces vowels and consonants originating from the throat, and vowel sounds that require great practice for non-Arab choirs (i.e. many Arabic transliterated “a” or “e” vowels sound somewhere between the IPA sounds “A” and “Ԑ”). Melismatic passages on voiced consonants enhance the choral sound palette and may produce good discussions about vocal resonance. Furthermore, ‘Arabic standard’ exists as a broad common dialect, but most Arabic melodies are defined by the vast number of local dialects that change, based on the origin of the melody and text. Without deterring the performer, such issues are best guided by a native speaker. Future Arabic choral publications may also consider audio aids with the choral score, which reinforce the process from outside of the rehearsal.

An introduction to this genre must include two well-known arrangers and the choirs who feature their arrangements: Dozan wa Awtar (Amman, Jordan), founded and conducted by Shireen Abu Khader, who arranges music for the choir; and, the Fayha Choir (Tripoli, Lebanon), founded and conducted by Barkev Taslakian, with Dr. Edward Toriguian as their arranger.

Jordanian conductor, Shireen Abu-Khader, began arranging music well before founding Dozan wa Awtar in 2002. Her works have reached more Arab and non-Arab choirs due to broad distribution [8] guided by her philosophy that expresses the “need [for] this music to be accessible for anyone to sing”. In the process of arranging, she values the “essence of the Arabic lines [and] the authenticity of the language and melody…The music has to still sound easy, familiar and close to the Arab audience.”[9] One of these familiar attributes Abu-Khader focuses on is the melismatic quality of the non-melodic lines prevalent in her arrangements. In their book Palestinian Arab Music, ethnomusicologists Cohen and Katz determined from a sampling of over three-hundred standard Arabic songs that between 60-100 percent of the musical material was melismatic.[10] Abu-Khader also relies heavily on the horizontal line of Arabic music while barely including portions of Western-influenced part-writing (passing tones, neighbor tones, etc…). For the choir, the result of her horizontal approach allows the voice to sing naturally and enables the exploration of vocal color. Dozan wa Awtar also commonly performs with solo instrumentalists or takt players.

Situated in the city of Tripoli, Lebanon, the Fayha Choir has largely performed Edward Toriguian’s choral arrangements. Though the melodies are mostly Levantine in origin, the arrangements are influenced by Western part-songs. On the request of their conductor, the pieces are intended for unaccompanied chorus and, therefore, much of the important Arabic percussive elements are represented in the choral parts. “I believe that human voice includes all the musical instruments, and it satisfies all tastes,” remarks their conductor, Barkev Taslakian. Toriguian’s largely homophonic approach tends to operate in Western harmonic progressions; some in the Arab choral world argue that this compromises the authenticity of this style. With the past influence of French culture, however, the mixing of harmonic textures with Arabic melodies is often part of modern Lebanese music. The works contain rhythmic momentum and exploit the use of vocal tessitura for dramatic musical effect. Fayha Choir’s successes, largely due to vocal and musical skill, have enabled Toriguian’s music to be performed in important Arab, European, and East Asian venues and competitions.[11] Among many of their accomplishments, Taslakian especially notes that the choir’s membership includes “all kinds of Christians, Muslims, all political parties, all social classes, showing that Arabs can do anything when they are united.”[12]

Public recognition of Arabic choral music and choral unity has occurred through the ‘ASWATUNA’ festival in 2008, which will again be repeated in the Fall of 2012, and, popular T.V. shows such as Arab’s Got Talent which exhibited the Fayha Choir to millions of viewers.[13]

Without seeking to define or confine music connected to such a diverse national, historical, and religious context, more dialogue will only enable the genre’s place and purpose in the choral and musical world. For instance, future syntactical discussion of Arabic choral music from conductors and arrangers can initiate a dialogue, resulting in greater interest, and more frequent performances. By combining Arabic music with the choral genre, how is the aesthetic balance maintained, and in what ways? To what extent is authenticity important? How do choral philosophies and practices influence the possibility for authenticity?

Despite the constraints on publishing companies, I hold that choral publishers act as a conduit of cultural preservation and education, not only for their own publications, but for music traditions across the world. Inclusion of Arabic choral music is not only marketable but necessary for the long-term development of Arabic and all non-Western choral genres.

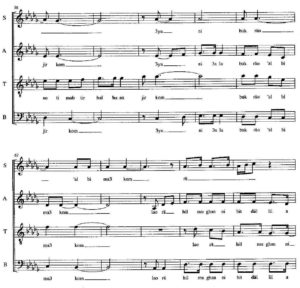

(Click on the image to download the full score)

Reprinted with the permission from the Publisher Dozan wa Awtar: http://dozanwaawtar.com/

Lao Rahal Soti, melody by Samih Shqer, arranged by Shireen Abu-Khader

(Click on the image to download the full score)

Reprinted with the permission Fayha Choir: http://www.fayhachoir.org/

Leyletna, melody by Zaki Nassif, arranged by Dr. Edward Toriguian

Lastly, it makes a difference for non-Arabs, especially those steeped in the Western tradition, to realize the difference between performing the music of other cultures versus engaging the music on its own terms. Striving for authenticity surely deepens the understanding of Arabic traditions. The pressure, however, of performing this music to the steepest degree of authenticity should not outweigh the value of cross-cultural education. For those seeking purpose alongside a music-for-music’s sake approach, Arabic choral music may be used as a tool to ease racial tension or Orientalist misunderstandings. In order to appreciate Arabic music for its own sake, all one must do is listen.

[1] For the purpose of this article, the term “Arabic choral music” refers to arrangements with more than one voice part, instead of in the traditional sense of a monophonic response to the soloist of a traditional Arabic ensemble.

[2] Dalal’s account in S. Broughton’s “Chava Alberstein: Israel’s Joan Baez,” World Music: The Rough Guide (London, Vol. 1, p. 364).

[3] Kjell Skyllstad, “Creating a Culture of Peace – The Performing Arts in Interethnic Negotiations,” Intercultural Communication, (Issue 4, November, 2000).

[4] Such discussions preclude the arranger’s wish for their music to be performed for more than one ensemble.

[5] The possibility to include scales with microtones exists when the microtone is executed as a passing note or in a quick figure of embellishment.

[6] A Mawwal is a non-metrical, improvisational, character-setting section of music which occurs before beginning of the metrical song. This sung genre is melismatic and may or may not include the text of the following metrical song.

[7] Gaber Asfour, “An Argument for Enhancing Arab Identity Within Globalization,” in Globalization and the Gulf, (London and New York, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2006), 146.

[8] The scores are available through Earthsongs publishing company and on the official Dozan wa Awtar website.

[9] Shireen Abu-Khader, interview by author, 20 July, 2012, Jordan to U.S.A.

[10] Dalia Cohen Ruth Katz, Palestinian Arab Music, a Maqam Tradition in Practice, (Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press, 2006), 197.

[11] The scores are accessible by contacting Fayha Choir through their website.

[12] Barkev Taslakian, interview by author, 30 July, 2012, Lebanon to U.S.A.

[13] A documentary of the 2008 festival may be accessed through this web link: http://www.aswatuna.com/aswatuna-2008.html.