No se trata solamente del espacio…

Dario De Cicco

Si pensamos en la música coral en el contexto de los espacios físicos y entornos que encontramos, debemos pensar en un aspecto muy cambiante de nuestra actividad musical que nos obliga a mirar – aunque de una manera rápida y sin profundidad- la historia del coro momo entidad. Los lugares en donde el coro canta varían de acuerdo a diferentes periodos de la historia de nuestra civilización, y estos cambios deben ser vistos como indicadores de continúo desarrollo, tanto en términos musicales como sociales. Estas dos dimensiones están íntimamente relacionadas: el lugar donde el coro actúa es parte de su existencia.

Pero, Hoy en día ¿dónde podemos encontrar información acerca del tema? Hay una serie de fuentes (las cuales los historiadores definen como “directas” e “indirectas” entre las cuales tenemos : imágenes (conocidas como “iconografía musical), narrativa (no necesariamente musical). Crónicas y registros judiciales, fuentes epistolares, tratados, documentos pertinentes a la administración eclesiástica, etc. Una masa considerable de información la cual, si leemos y cruzamos referencias, nos permite reconstruir, con un grado razonable de credibilidad, la evolución de un aspecto muy especial del “hacer música juntos” el cual ha sido siempre una característica de la experiencia humana.

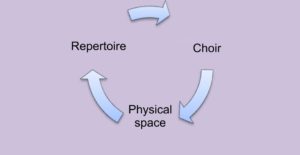

Investigando los espacios utilizados para realizar la actividad coral, implica también el pensar acerca de la relación que el espacio ha tenido en la concepción y desarrollo del repertorio coral: podríamos empezar con las monodias gregorianas institucionalizadas por los Benedictinos en su contexto monástico del Ora et labora y que continuaron con el popular repertorio del Renacimiento presentado en la corte durante las fiestas y otras ocasiones especiales. Este es un tema que podría ser desarrollado a través de un sinnúmero de ejemplos, llevándonos a esta primera relación circular:

La composición de formatos corales no ha sido siempre la misma, ha variado de pequeños grupos de solo algunos cantantes, hasta grandes cuerpos de hasta sesenta miembros, y llegando a los enormes coros del siglo XIX. Esta grande variación numérica ha tenido un efecto impactante en los recintos utilizados para eventos musicales y en la organización de los espacios.

La primera etapa en nuestra exploración ideal es mirar a las culturas precristianas donde la música coral formaba parte integral de las presentaciones rituales y teatrales, convirtiendo de esta manera a la música coral en una actividad socialmente legítima e importante. En el caso del ritual religioso, el coro está reunido alrededor del altar, estableciendo un diálogo directo con los celebrantes y con la divinidad. Este contacto cercano denota una dimensión cultural significativa, sugiriendo que el coro forma parte integral de la existencia humana.

Cuando se presentaban las tragedias en el teatro, el coro se paraba en un espacio semicircular, destinado para este fin al frente del escenario. Este lugar se llamaba la “orquesta”. Allí podían cantar y al mismo tiempo bailar.

El coro era considerado uno de los actores, participando en toda la presentación.

Sabemos que la bien luchada afirmación de la Cristiandad no pasó por alto la participación coral, aunque no hay mucha información disponible al respecto. Algunas imágenes encontradas en las catacumbas en el área de Roma sugieren que cantar juntos era un elemento común en los servicios litúrgicos matutinos.

En la Edad Media la experiencia de cantar en un coro y los espacios donde esto se hacía estaban conectados con el espacio que ocupaba la música en la sociedad contemporánea. El vínculo entre dos dimensiones de la vida humana – educación y fe – es especialmente significativo. La música coral se cantaba usualmente en espacios privados cerrados tales como iglesias, monasterios e instituciones educativas de la época. Había muchos más espacios religiosos que seculares, aunque parece claro que una gran parte del repertorio medievales de la música secular pretendía ser para una presentación coral .

El hecho de que San Benedicto de Norcia (480 – 547) dedico su Pauta la Regula Monsteriorum a la práctica coral, sirve de testigo de la importancia del papel que cumplía la música coral, un papel que permaneció constante a través de los siguientes siglos. La disposición física del coro es una metáfora de la armonía, ordenada y medida, existente entre el cuerpo y el espíritu. El posicionamiento de la comunidad monástica para las oraciones cantadas es una expresión funcional del deseo de rendir culto y honrar a Dios, esta es la clave para entender el orden preciso de parase, sentarse, interactuar, y así sucesivamente. Esto no es un rigor estéril sino una expresión de los valores que fundamentan la experiencia monástica.

A finales de la Edad Media (100 – 1492) se realizaron en las iglesias algunas presentaciones teatrales inspiradas en los Gospels. Aquí el papel del coro era de vital importancia. Este fue el primer paso en un proceso que llevaría al desarrollo de repertorios específicos – albanzas – para los cuerpos a quienes se les confiaba efectuarlas: las confraternidades. Por lo tanto, la función coral generaba inclusión social.

El renacimiento fue un tiempo especialmente fértil para la música coral, tanto sacra como secular. El nacimiento de la Corte como un modelo de organización social le dio un apoyo importante a la proliferación de presentaciones corales en tiempos significativos, y los espacios dedicados para el coro incluían maravillosas salas de recepciones y ese nuevo invento, el teatro de la corte. Los repertorios corales se desarrollaron y florecieron a través de una estrecha relación con la poesía y los espacios dedicados a la música coral en ese entonces enfatizaban las dimensiones sociales y culturales de las cortes

Al mismo tiempo, la producción y ejecución de la música sacra floreció, con la ayuda de la proliferación de las escuelas de música sacra (scholae cantorum), creadas con el objetivo de capacitar cantantes profesionales que serían capaces de proveer el número necesario de estructuras utilizadas en la música polifónica. Cantantes profesionales competentes eran necesarios ya que la música coral se había convertido en una música mucho más compleja (contrapunto) y requería de no solamente una habilidad genérica para cantar sino de una pericia notable en emisión y expresividad. Estas escuelas dieron lugar a un sinnúmero de eventos musicales en los escenarios más extraordinarios de la Cristiandad, lugares célebres por la gran belleza de su decoración, dando como resultado una serie de diálogo entre las artes visuales y la música: el epicentro de todo era el Hombre y su voz.

En esta época la division de la música en dos partes. Sacra y secular, era evidente en varios niveles – la música escrita, organización formal de las obras, escenarios para la música coral – y la práctica de la música coral se desarrollo en un contexto cultural dinámico. En la música secular, los primeros instrumentos musicales aparecieron determinando ciertos requisitos en su posición y la manera en que se balanceaban con las voces que cantaban. Un aspecto importante de esto, es el desarrollo de la música policoral en Venecia: dos coros, separados espacialmente, cantaban alternadamente. Este tipo de música estaba determinado por el diseño arquitectónico de la Basílica de San Marcos, y es uno de los ejemplos de la relación circular mencionada anteriormente.

Con la llegada del melodrama en el siglo XVI, la música coral redescubrió su dimensión escénica: el teatro. Podríamos ver esto como ganarse un espacio que siempre había estado destinado al coro. Ya no existía un espacio exclusivo funcional para su actividad; por el contrario el coro tenía un lugar en escena tal como los otros actores. La prominencia del coro en una ópera varió muchísimo, de un siglo al otro y de un país Europeo a otro en términos tanto de espacio como de tiempo. Los estudios de historia de la música han sostenido siemore que el posicionamiento del coro en relación con la orquesta tiene su propio significado, y en este aspecto podemos ver también variaciones notables en su presencia en el escenarioy la posición detrás o junto a los instrumentos musciales. Cada situación requería de sus propias estrategias para que fueran funcionales tanto a la salida de sonido como para los requerimiento de una dirección orquestal naciente y en algunos casos incierta, la cual en varias ocasiones se le confiaba a varias personas. Por lo tanto no existía una estructura única, sino un número de estructuras diferentes, frecuentemente híbridas. Los numerosos diseños de los teatros o de presentaciones particulares nos proveen de información interesante al respecto.

A la hora de decidir dónde ubicar el coro depende, y siempre ha dependido, en gran parte del estilo de dirección del director. El uso o no de la batuta y el desarrollo de la teoría de dirección han sido factores determinantes en la escogencia de una posición en el escenario sobre otra. Frente a la orquesta, detrás de la orquesta o al lado de la orquesta. Para Giuseppe Verdi el coro era un elemento importante de sus óperas y con frecuencia les confiaba la delicada tarea de personificar y dar voz a los valores de una sociedad determinada. Esta reflexión se ha basado principalmente en la presentación musical en lugares y espacios visibles a la audiencia. Debemos pensar también en la ejecución de música coral en comunidades monásticas, la cual era con frecuencia realizada sin ser vista por otros – especialmente bajo las estrictas reglas del pasado-, en ese entonces como ahora la música coral era funcional para las prácticas de fe. ¿es lo mismo cantar que escuchar? ¿Cambian los parámetros básicos? ¿y acerca de la producción del sonido? ¿Qué relación existe entre sonido y visión en nuestras presentaciones de concierto?

Otro aspecto a tener en cuenta es la escogencia de los materiales de construcción de los lugares donde el coro se presenta. ¿Por qué se usaba tanto la piedra en la Edad Media y después? ¿Era solamente porque estaba disponible o es una elección consciente? Esto puede parecer un tema de poca importancia, pero ¿cuántos coros han visto su arduo trabajo frustrado por una acústica pobre cuando se presentan en edificios de concreto reforzado?

Estas consideraciones son importantes en una sociedad inclinada en su mayoría a una dimensión visual incluso cuando la presentación musical y el escucha están involucradas. Sería bueno si los coros – in el sentido de todos los coristas involucrados – pudieran tomar estos aspectos en cuenta a la hora de planear un evento musical. Con frecuencia la elección del lugar está determinada por el director o los organizadores. El tema debería ser discutido señalando que el hecho de definir dónde es mejor ubicar a las sopranos, a la derecha o a la izquierda, donde ubicar al coro con respecto al órgano, son aspectos que realmente hacen la diferencia.

Espero que estas reflexiones puedan estimular una conciencia crítica de los muchos aspectos de la música coral en todos aquellos que practican este arte, así lo hagan de una manera profesional o aficionada, y que puedan darse cuenta que la experiencia de nuestros predecesores no es un cuerpo de conocimiento destinado solamente a una élite o conocedores refinados, sino que constituye un conocimiento vivo el cual – incluso después de siglos – puede encender el entusiasmo y ayudarnos a desarrollar nuestras habilidades en “hacer música”

Dario De Cicco es graduado de Pianoforte, Música y Enseñanza de la música coral y Dirección coral. Se ha especializado en el canto coral y el canto Gregoriano en los principales centros de Italia y de Europa. Frecuentemente publica los resultados de sus estudios musicales e investigaciones en una serie de revistas (incluyendo Bequadro, Musica Domani, Il Rigo Musicale, y otras) y dicta cursos de canto coral, semiología y paleografía Gregoriana en una seria de monasterios en Italia y otros países Europeos. Es colaborador con Editions de Solemnes y fue responsable de la edición Italiana de un texto de G. Hourlier publicado como “La notazione dei manoscritti liturgici” (2006). Para la editorial OTOS en Lucca a editado oratorios de Giacomo Carissimi como “Felicitas beatorum” (2004), “Lamentatio damnatorum” (2004), “Jephte” (2006). Es Presidente de la sección La Spezia de la Sociedad Italiana de Educación Musical SIEM, y miembro del comité nacional de la misma organización donde es responsable de actividades de las diferentes secciones. De igual manera es miembro de varios comités permanentes de estudios nacionales e investigación conectados con el SIEM. Trabaja con una serie de colegios y asociaciones musicales a nivel nacional y es instructor en proyectos relacionados con enseñanza experimental en las áreas de enseñar a escuchar y enseñar música en escuelas primarias y de infantes. Email: dariodecicco@alice.it

Dario De Cicco es graduado de Pianoforte, Música y Enseñanza de la música coral y Dirección coral. Se ha especializado en el canto coral y el canto Gregoriano en los principales centros de Italia y de Europa. Frecuentemente publica los resultados de sus estudios musicales e investigaciones en una serie de revistas (incluyendo Bequadro, Musica Domani, Il Rigo Musicale, y otras) y dicta cursos de canto coral, semiología y paleografía Gregoriana en una seria de monasterios en Italia y otros países Europeos. Es colaborador con Editions de Solemnes y fue responsable de la edición Italiana de un texto de G. Hourlier publicado como “La notazione dei manoscritti liturgici” (2006). Para la editorial OTOS en Lucca a editado oratorios de Giacomo Carissimi como “Felicitas beatorum” (2004), “Lamentatio damnatorum” (2004), “Jephte” (2006). Es Presidente de la sección La Spezia de la Sociedad Italiana de Educación Musical SIEM, y miembro del comité nacional de la misma organización donde es responsable de actividades de las diferentes secciones. De igual manera es miembro de varios comités permanentes de estudios nacionales e investigación conectados con el SIEM. Trabaja con una serie de colegios y asociaciones musicales a nivel nacional y es instructor en proyectos relacionados con enseñanza experimental en las áreas de enseñar a escuchar y enseñar música en escuelas primarias y de infantes. Email: dariodecicco@alice.it

Traducción del Ingles por Maria Catalina Prieto, Colombia