Approaching contemporary choral music development – with open ears and alert minds

Stephen Leek, IFCM Vice President and composer

We all know that a choral program needs to embrace many musical, non-musical and technical elements. The healthy technical aspects of voice production and choral singing must be taught. The well-being of the singers must be monitored. Building a choral community that is supportive of its members must be nurtured. The skills in the “Art” of Choral Singing must be shared.

However, one of the most important ingredients to building a healthy choir is often overlooked. That is, the development of a courageous approach to creativity and composition within the choir – processes that actively involve singers, conductors … and composers.

Let’s face it, without composers, choirs would not exist. Without composers whose music looks to the future, choral music seriously runs the risk of becoming just another product of antiquity. Some would even suggest that without preparing for the future by nurturing a creative approach at every level of choral activity, choral music might indeed be a dying art form. There will always be people who will want to sing in a communal way, so I doubt that will ever happen, but this is an issue that needs to be addressed by all of us, now.

A common feature of the most distinctive and – some would argue – most successful choirs around the world is that they have, as a regular part of their choral activities, a conscious pursuit of creative engagement in some form or other. It is common for a choir that works regularly with compositional concepts to create a unique sound and identity for itself based on this creative process. I believe it is critical that all healthy choral programs have some form of active creative component, not only to keep choral music alive, but also because it has numerous long-term benefits for the choristers, the conductor, and the community in which the choir sings.

Writing choral music has different compositional challenges to that of writing instrumental music – some composers do it very well and some other well known composers do not. What is common to most composers of innovative choral music is that at some time in their lives they have sung in a choir … they know what it feels like to sing as part of the team … they know what courage it takes to sing collectively in front of an audience … they have a better understanding of what the voice can and can’t do – and, most commonly, these composers sang in choirs when they were young.

Some would say that composers (like conductors) can’t be taught, but can learn and grow through positive and inspirational experiences … when they are young. Composers, like conductors, do indeed learn their Art and craft from experience, by doing it, by feeling it and by being inspired by it, most often when they are young.

So, if your choral program does not have a major creative component to it, then you, as conductor, are depriving your singers of the opportunity to evolve and develop in this way. How then do we start to present creative compositional ideas to young singers in a non-threatening, yet meaningful, way?

Simple. You play – you play with sounds, you play with ideas, you play with anything vocal that comes into your head. You have fun, you laugh, you can be silly … I call it Playtime. Playtime can be part of your warm-ups, part of your rehearsal process and sometimes part of your performance practice. It can be part of the repertoire that you choose. Playtime encourages different ways of looking at the notions of choral singing. It stimulates the aural imagination. It can develop compositional concepts and ways of thinking and hearing without anyone even knowing that it is happening.

In warm-ups, make up simple patterns, encourage the singers to invent short phrases of sound rather than just singing stock scales and arpeggios. Sing short sequences in two parts at different intervals. Put two different sequences together – one after the other – on top of each other … Mix it up, be creative, be spontaneous, be surprising, be inventive, be funny, be courageous! In warm-ups throw sounds to the choir, have them catch and throw different sounds back at you – connect the physicality of sound with movement. If you are initially afraid of this sort of activity, have the choir simply copy you, then share the leadership around. Move on to ‘calls and responses’. Then, engage the compositional brain in a different way by requesting that the response must include a musical element from the call. Share the leadership around – let the singers become accustomed to making contributions to the process. Ask for ideas, try them out … very quickly you will discover that your choir is full of ideas. This process also encourages the all-important development of critical listening, and analytical skills – skills that are essential for the development of composers, and it encourages free-thinking in your singers outside of the standard musical boxes.

Remember, that if you are not prepared to do it yourself, you choir will not do it. Show your “Choral Courage” and throw yourself in.

In rehearsal, select a difficult passage out of one of your pieces and deconstruct it – isolate the elements of it, spontaneously make something new out of it, trust yourself. Create a texture, a musical gesture, or a sequence, or an ostinato, or a canon, or a sound cloud, or a fanning cluster … the list of possibilities goes on! Join several of them together … rehearse it, perform it. Above all, be brave and don’t be upset if things don’t work out as you expect … It is actually even better if your ideas don’t work because the singers learn from making mistakes, (indeed composers learn from making mistakes) and by doing so they will discover more about compositional processes, and not be so afraid of taking artistic and musical risks themselves.

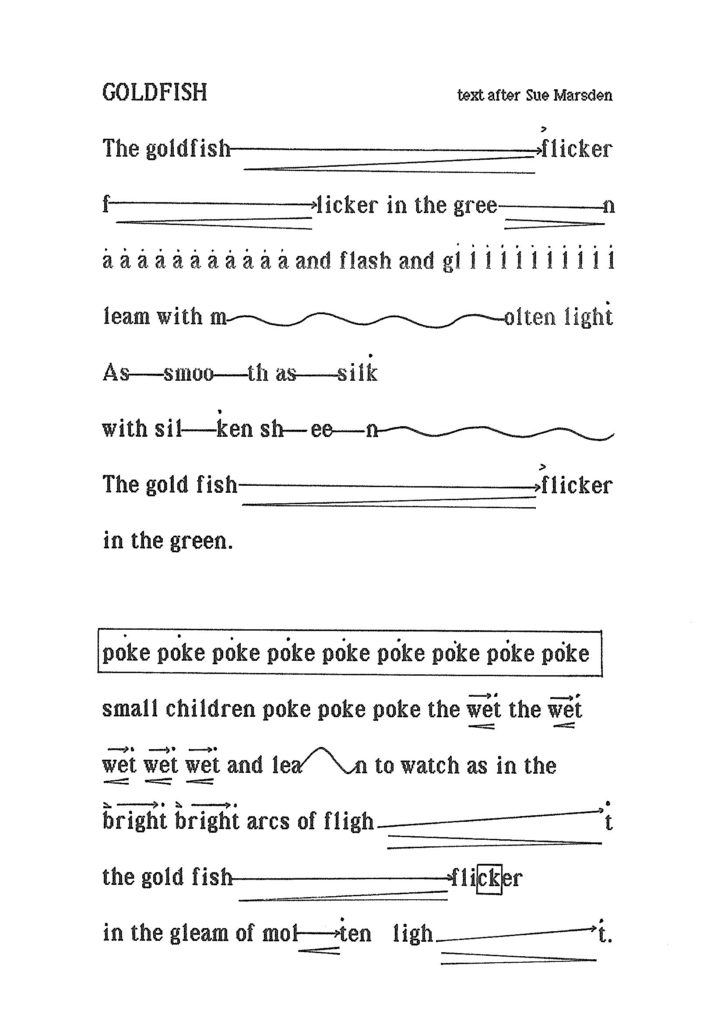

When choosing repertoire try not to take the safe options, but rather select works that offer listening and compositional challenges to the singers, the conductor, and perhaps even to your audience. Take for example a very simple text and graphic notated set of pieces, Telling Tails

These sorts of graphic scores are great for any age (and there are many of them around) because they introduce to the singers the possibility that choral singing and choral music are not just about the notes, the rhythms and the dynamics, but also about inventing, about making things up, about taking risks, about trying things out, perhaps using some of the techniques that you have discovered – free singing, clusters, textures, dramatic contexts … and a raft of other extraordinary possibilities.

To take the ideas further, why not introduce the concepts in a notated form. Split Point is a small piece for young singers about a well-known lighthouse in Australia (available www.stephenleek.com).

Here, I wrote a very simple melodic line that goes through the usual motions of unison, and canon with an accompaniment … but then a boxed section appears where the singers perform the passage freely in their own time creating a textured cluster which resembles “a flock of seagulls hovering around the rotating light of the lighthouse”. Once this visual image is in place, the singers have no problem creating the required sound texture and overcome their fear of performing with such individual freedom and choice.

Later in the piece I use simple word painting techniques to suggest the running up and down of the spiral staircase which winds its way up the inside of the lighthouse. If you discuss the principles of word painting with your singers, they will very quickly begin to understand the important role of this technique in choral music, and the role it plays in connecting the music with the words.

Unlike instrumental music, the use of words in this way is a unique feature of choral and vocal music. The words and context of a piece are so important to choral music, and I find it frustrating hearing new works that negate this unique part of choral singing altogether by using no text, nonsense texts, or yet another generic Latin text – the sounds may be pretty but the context is almost meaningless.

To develop creativity further there are several different directions a choir director could take. The most obvious is for the singers to create, and then ultimately write, their own compositions. If you as a choral director don’t feel you have the confidence to initiate this process – why not invite a local or student composer from your community to help? I guarantee that the composer will learn more about choral music than you can ever imagine … and they most likely will enjoy it and want to do it again!

Another less confronting route would be to choose repertoire for your choir that is adventurous in its spirit and is more contemporary in its techniques. Too often, I think, conductors choose repertoire that is too safe and too easy. The result of this is that the choir never really develops the skills that enable them to move more freely through repertoire from around the world, or to enjoy the choral developments that occur in new work. And, as I stated earlier, you are depriving your singers the opportunity of personally and artistically growing through composition and musicianship.

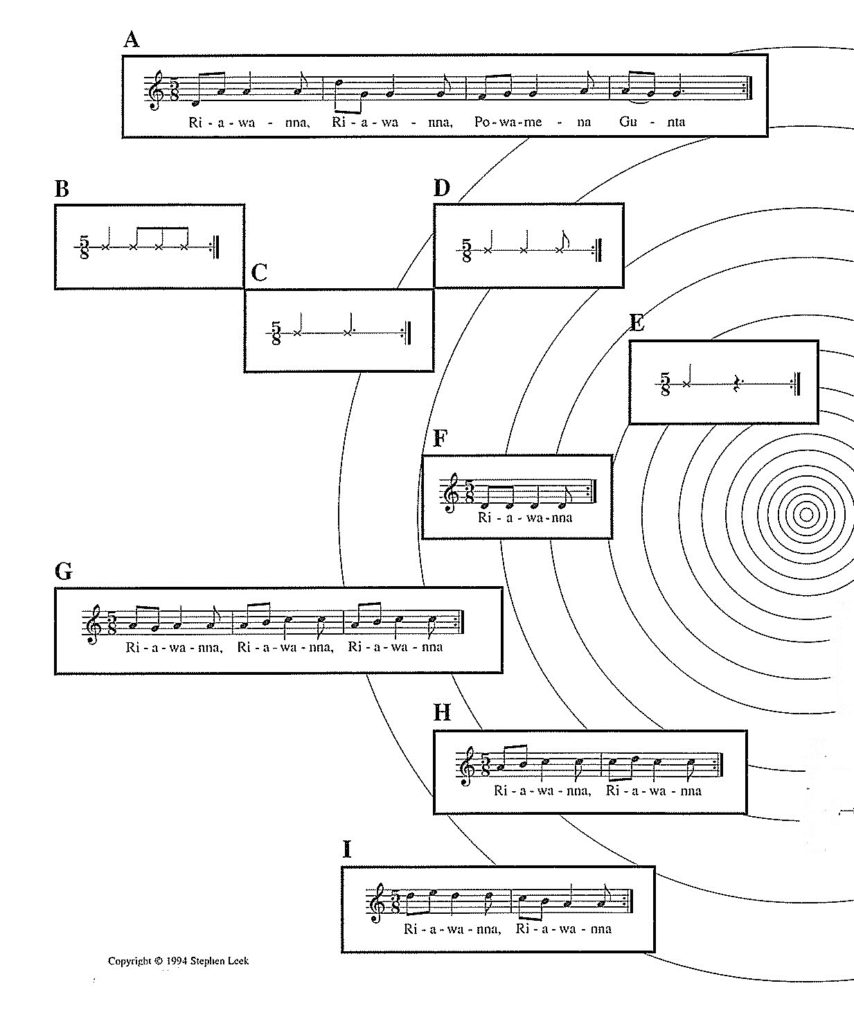

Within the framework of an indigenous Australian word, which means “the circle of life”, Riawanna is suited to any age of singer. It is a most useful piece in helping young singers identify the raw ingredients and essential materials of a work. The process of making their own music out of the materials provided assists singers in understanding the construction process of a composition. It also helps them to understand that you do not need lots of ideas or materials to build a successful piece. Apart from the rhythmic component, this piece of any duration (or complexity) also explores basic harmonic singing techniques (which encourages mouth shape experimentation) and the exploration of choral color (which aids a choir’s development in every possible way – no matter what music they are singing).

How does all this creative playing translate into mature choral works for adult singers?

Adult singers can be introduced to contemporary music in many ways. Repertoire selection is the most obvious way. There are many, many contemporary works around now that gently ease singers into newer techniques and sounds. One such work is Kondalilla – a movement of a much larger work Great Southern Spirits (available www.stephenleek.com).

Kondalilla is a work for mixed voices of unlimited duration, the female singers freely sing given materials in an improvisational manner, yet in a carefully constructed form that sits on top of the structured male voice parts. This work evocatively captures the context of the Australian rainforest and the traditional spirits that lurk in the waterfall and in the still water of the stagnant pools … It is a favorite of many singers who will openly tell you that they don’t like ‘contemporary music’! I hate to tell them … but this is actually ‘contemporary music’.

Other movements of Great Southern Spirits offer different challenges to the singers and to the audiences, and the general response for this work is one of overwhelming excitement. These days contemporary music is as diverse as the composers who write it. With care, thought, and some preparation, any new music can be exciting, challenging, an adventure, and we should all be able to find something exciting and worthwhile in it, if we develop the tools to learn how.

Do we need to work with composers? Yes we do. As choral musicians we need to embrace composers in every aspect of our work. Choral music composers are the creators of the sounds, the narrators of our emotions, the tellers of our stories. Composers and adventurous, creative composition is our future and indeed, the future of choral music. Composers come in all shapes, sizes and genders, and from all cultures. There is most likely a composer living near where you live right now.

The easiest way to engage composers in your community is firstly by finding out who they are and simply inviting them to your concerts. Composers are real people too and enjoy being welcomed into a musical community. Over time they may become so excited about being part of your community that they might even offer to write you a complimentary work … but be warned, you must be prepared to pay for good music: like everything in life, choral music composition is not free – composers have mortgages too! I really believe every choir should regularly budget for the commissioning of new work – just like you would budget for everything else to do with the choir – the rehearsal venue, the uniforms, the travel costs, the biscuits at tea-break etc. If you respect the livelihood and skills of a composer by paying them appropriately for their skill and talent, then they will, in turn, respect you and choral music.

Investing a portion of our annual budgets in the commissioning a new piece can be a risk – but it is a risk worth taking, and it is a risk we all need to do on a regular basis. “Be Brave, be Courageous!”

Here are a few basic steps we can all take to nurture composers and ultimately ensure a brighter future for choral music:

- Never use photocopied music without a license to do so from the composer or the publisher.

- Budget for the purchase of music.

- Always pay the appropriate fees for performing choral music to the performance collection agencies in your country.

- Seek out composers living in your area and befriend them.

- Budget for the commission of new work on a regular basis.

- Be courageous in your choice of composer – don’t always go for the safe and well worn options.

- Perform at least one new piece of choral music in every concert.

- Always invite the composer to attend the last rehearsals and the premiere performance.

- Always acknowledge the presence of the composer of a work in a concert.

What is the future of choral composition? I wish I knew. What I do know, however, is that we must take active steps now to prepare our singers, our choirs, our conductors, and our composers (when they are young) to be able to participate in whatever exciting music evolves in the future – and there are some very simple initial steps that can take choral directors down that road right now. And by opening our ears and keeping our minds alert to the wonderful creative possibilities of the Choral Art, we can ensure that there is indeed a bright future ahead.

Edited by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood