By Aurelio Porfiri, choral conductor and teacher

Gregorian chant has known a strange twist of fate in recent decades: on the one hand, implementation of the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) made the only repertoire claimed by the Catholic Church as its own a de facto foreigner in its own country. (I will not delve here into that topic, which is very hotly debated in church music circles and is a source of never-ending debates.) On the other hand, this repertoire has experienced a great revival thanks to CDs of both traditional chant and pop arrangements (by Enigma and similar groups) and, especially, to scholarly studies that in recent decades have shed new light on it. In addition, one cannot help noticing how ‘cool’ the Middle Ages have recently become, thanks to movies and other works of fiction that portray characters and times clearly inspired by the ‘Christian centuries’, for example the Lord of the Rings trilogy by Tolkien (both the books and especially the movies) or the TV series Game of Thrones. And since Gregorian chant is, as we all know, the quintessential soundtrack of medieval times, it too benefits from the medieval revival. Thus it is worth exploring a very interesting development in Gregorian chant studies – Gregorian semiology – knowing that, whether we like it or not, Gregorian chant lies at the beginning of the western musical tradition and as such is worthy of being more deeply understood[1].

If there is one place most strongly associated with Gregorian chant from the middle of the 19th century to this time, it is without doubt the Abbey of Solesmes in France. Why is this so? The reason is the great impulse given it by the restorer of monastic life and the champion of Roman liturgy in France, Dom Prosper Gueranger (1805-1875). The Abbey of Solesmes was the center of a Gregorian chant movement that produced scholars among its monks who have led this movement up until the current time. In the middle of the 19th century, serious study of this repertoire was conducted in hopes of achieving a very important goal: to restore the melodies to their original form and beauty (to the extent that this was possible given the manuscripts available) after several centuries of corruption had made them almost unrecognizable. This deterioration is clearly represented by a 17th century edition of chant melodies, the ‘Medicean’[2].

This research suggested new ways to understand chant. Probably the most important developments in chant studies in recent decades are in two specific fields: one, a better understanding of modality thanks to another Solesmes monk, Dom Jean Claire (1920-2006), the other, the development of a Gregorian semiology.

What is Gregorian semiology? It is a new understanding of the meaning, diversity and values of the ‘neumes’ notated in the medieval manuscripts. Neumes (signs used to represent melodic lines, one neume being all notes sung on a given syllable) were of course already known by great Gregorianists of Solesmes like Dom Joseph Pothier (1835-1923) and especially, Dom André Mocquereau (1849-1930), but were reconsidered and given new life thanks to research by another monk of that Abbey, Dom Eugène Cardine (1905-1988). Indeed, Pothier’s and Mocquereau’s ground-breaking studies led to what is considered the first phase of the Gregorian chant restoration, with Cardine and Claire the main representatives of the second phase, which began in the 1950s (Turco 1991, page 38). As stated above, Dom Cardine understood that the neumes, the signs, can tell us more about interpretation and rhythm than was previously understood; something had been missing:

“(…) Cardine concentrated his attention upon that extreme diversity of signs found in the most ancient manuscripts. He gradually became convinced that this diversity is intended to express the particularities and the delicate nuances of expression within the interplay of durations and intensities”

(Combe 2003, p.15).

The book that was to spread this new idea of semiology is basically a collection of lessons he delivered at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome, lessons gathered in his Gregorian Semiology. This publication has now been translated into several languages. The idea behind Dom Cardine’s new understanding of chant is simple: despite the fact that his great predecessors (notably Pothier and Mocquereau) were familiar with the neumes, they missed a deeper understanding of what lies in the neumes themselves. They were important not just for the reconstruction of melodies but also for giving fundamental indications about rhythm and expression. We know that the most popular rhythmic theory was the one developed by Dom Andre Mocquearau in his two-volume book Le Nombre Musical Grégorien (A Study of Gregorian Musical Rhythm), in which he attempts an explanation of the rhythm of Gregorian chant that would become very popular in the twentieth century. This theory suggests the rhythmic subdivision of Gregorian neumes into groups of two or three notes governed by an accent called ‘ictus’. This theory represented a breakthrough in its time but also had its limitations. Indeed, it seems that even in Solesmes the choir never really followed the rhythmic theories of Dom Mocquereau, and today they are considered outmoded. As already mentioned, the theory that was to bring life back into the inner soul of the neume was Dom Cardine’s semiology.

His ideas were guided by two criteria:

“The first belongs to the material or graphic order, and considers the design or configuration of the signs. The second belongs to the aesthetic order, and considers the musical context in which each sign is used. It is a matter of investigating the convergence of these two criteria, and of comparing the instances identified in each of the different notations” (Combe 2003, p.16)

Why is it called semiology? At first Dom Cardine preferred to call this new science ‘Gregorian diplomatics’ but the name did not have a good ring to it; someone suggested he call it ‘Gregorian semiology’, and it has been known by that name ever since.

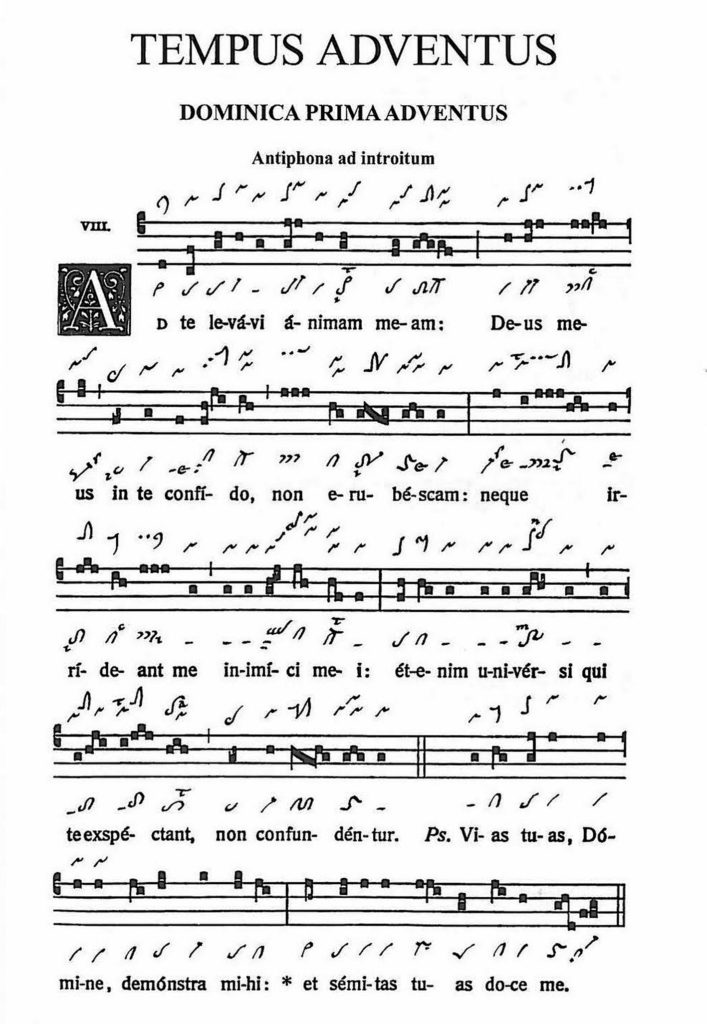

The practical book for the performance of Gregorian chant, following the semiological principles rediscovered by Dom Cardine, is the Graduale Triplex. Together with the square notation of the Vatican edition, it also uses the neumes from two ancient and reliable neumatic families, Laon and St. Gall. Today indeed we also have the Graduale Novum, a quite recent addition to the list of chant books, with many improvements designed to restore a more authentic version of the melodies.

(Click on the image to download the full score)

Many scholars after Cardine (some of them his students at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome) have continued the investigation of semiology. We cannot forget here Nino Albarosa, Alberto Turco, Luigi Agustoni, Johannes Berchmans Göschl, Giacomo Baroffio, Columba Kelly, Robert M. Fowells and many more.

Is it possible to perform Gregorian chant without using the theory of Dom Cardine? Of course it is, and indeed several chant choirs prefer not to use the semiology. But I still think it is very valuable to use because the signs, when considered in a semiological context, provide more information for a good performance of chant; they help performers deepen their understanding of how the melody clothes the text. Indeed, the great intuition of Dom Cardine was to ask why the ancient scribes had to spend time shaping the same neume in different ways. His answer was: because they wanted to tell us more about the interpretation and the nuances; they wanted to communicate a written gesture. It is a way to look ever more deeply into the soul of chant. We can say that semiology is an exegetical tool, one that provides more insights on a piece the choir will perform. The hope is that, along the path of Dom Cardine, more and more discoveries will enlighten the way for those who continue to regard chant not as a relic of the past, but as a living tradition.

[1] I want to thank Professor Nino Albarosa, renowned chant scholar, who kindly agreed to read this article and offered a few suggestions for improvement. Of course any imperfections must be ascribed to me alone.

[2] There are several reasons for this decay, having mainly to do with changing musical tastes over the centuries that brought consistent alterations in the melodic and rhythmic elements of chant.

REFERENCES

- Agustoni L., Göschl J.B. (2006). Introduction to the Interpretation of Gregorian Chant (Columba Kelly, Trans.). Lewiston, NY (USA): Edwin Mellen Press (Original Work published 1987).

- Albarosa N. (1974). La scuola gregoriana di Eugène Cardine. Rivista Italiana di Musicologia IX, 269-297.

- Albarosa, N., Porfiri A. (2008). Ad Te Levavi Animam Meam. On the way to discovering Gregorian Chant (Lazina Gheyselinck, Trans.). Pohlheim (Germany): Edition Music Contact.

- Cardine, E. (1982). Gregorian Semiology (Robert M. Fowells, trans.). Brewster, MA (USA): Paraclete Press (Original Work published 1968)

- Combe, P. (2003). The Restoration of Gregorian Chant. Solesmes and the Vatican Edition (Theodore Marier & William Skinner, Trans.). Washington (USA): The Catholic University of America Press (Original Work published 1969).

- Mocquereau, André (1908). Le Nombre Musical Grégorien ou Rythmique Grégorienne. Tournai (France): Desclée & Cie.

- Porfiri, A. (2003). Canto Gregoriano e Polifonia. Liturgia, n.176.

- Turco, Alberto (1991). Il Canto Gregoriano. Corso Fondamentale. Rome (Italy): Torre d’Orfeo.

Aurelio Porfiri is Director of Choral Activities and Composer-in-Residence for Santa Rosa de Lima School (Macao, China), Director of Musical Activities for Our Lady of Fatima Girls School (Macao, China), Visiting Conductor for the Music Education Department of Shanghai Conservatory of Music (China), and Artistic Director of Porfiri & Horvath Publishers (Germany). His compositions have been published in Italy, Germany and the USA. He has contributed more than 200 articles to several publications on topics related to choral and church music. He is the author of five books. Email: aurelioporfiri@hotmail.com

Edited by Anita Shaperd, USA