By Peter Phillips – Director of the Tallis Scholars

The architecture of polyphony

One potentially unhelpful aspect of how polyphony was written is the almost total lack of repeating material, which can test a conductor’s ability to shape a piece. The standard motet or mass movement written after about 1520 is made up of a series of imitative schemes, a new set of imitative points required by every new phrase of words: Palestrina’s Sicut Cervus is a classic case. Given that ever since, and especially in sonata form, most music has relied on recapitulation both for its intellectual and emotional effect, how is one to present such a bland formula? Where will the points of contrast be? If there is no recapitulation, there will be no sense of building to a repeat and through it to the final leave-taking. One can rely on a very consistent compositional idiom in polyphony, but not on a sense of beginning, middle and end because there was no attempt to use harmony as a controlling or in any way emotive background force. The harmonic background in polyphony is often as simple as could be, which is why it is such a travesty to sing it in buildings which are so reverberant that all anyone can hear of the part-writing is a series of constantly repeating very basic chords. Here again the modern conductor may have his preconceptions challenged.

The clue is to have a good sense of the overall architecture of the music, and to judge each piece precisely on its merits. If the music is straightforward it is useless to pretend it is otherwise. There should be no doubt that every piece of polyphony, however elementary in idiom, can be made effective in performance if the basic sound of the group is involving, though one might think twice about programming simple music on the big occasion: Tallis’ Dorian Service is not suitable for a big symphony hall event. But even the grandest pieces follow this basic plan of a series of imitative sections connected only by the strictly controlled musical idiom; they may ebb and flow with the greatest invention and polyphonic effect, but, unless they have chant cantus firmus as scaffolding, they hardly ever advertise any sense of a journey from an initial emotional stand-point to a subsequent one. Renaissance music has much more to do with contemplating a fixed state of mind, proposed by the words, than progressing through a sequence of them. Nonetheless the modern conductor will be expected to do something more with his material than create an unvarying sound, especially if the piece in question, like some of the grander English antiphons, lasts nearly 20 minutes as a single movement. This is where a sense of architecture is crucial. A piece like Tallis’s Gaude Gloriosa would challenge the control of the most experienced symphonic conductor, if the two were ever to meet, because its few cadences all contribute something to the total picture, all of them carefully placed not only to round off a section, but as stepping stones to the ‘Amen’ which caps the whole vast structure. I believe it is necessary for the conductor to have a sense of exactly where those cadences are in relation to the whole as he or she approaches them, if he is to make the most of the explosive final pages. In fact, Gaulle Gloriosa, although amongst the longest of these single-movement pieces, is not one of the more sectional. It is a measure of the sophistication of the style by Queen Mary’s reign that Tallis could write something which flows so irresistibly over such a substantial canvas. There are many rather shorter pieces which can seem cut up for no reason other than that the composer must move on to the next phrase of words. Parsons’ O Bone Jesu is a good case in point. The placing of the last section — ‘Fac mecum’ — poses a classic challenge to a conductor. Everything seems to have been said in the music already; the obvious framing of the sections with a homophonic phrase beginning with the invocation ‘O’ has happened several times, the one before ‘Fac mecum’ having been particularly powerful. How can one build through this unwanted full-stop, especially as there is going to be no help further on through revisiting of old material? The answer is: don’t pretend it is anything other than it is, and come to it with an exact sense of what has happened in the music up to that point, and what is to follow. After the big cadence which precedes it one can do no other than withdraw. To try to maintain the intensity would feel false, yet within a page or two one is going to be singing the ‘Amen’. I believe the power of that ‘Amen’ will depend on how well the performers have prepared for it from the very beginning, and not by suddenly remembering it when they come to ‘Fac mecum’.

Parsons tests one’s architectural sense more than usual in O Bone Jesu, for all that conductors trained in the more symmetrical constructions of later music are going to find every polyphonic composition testing in this way. Parsons was still writing in the mid-century idiom, and it is true that high renaissance music can come nearer to later and more familiar practice. A motet like Byrd’s Civitas sancti tui is not architectural in the way I have just described because it so hangs on its text that the logic of the words alone carries us through. One would have to be made of stone to fail to make something of the last section — ‘Jerusalem desolata est’: it is not necessary to plan for it in the same way as for the Amens in the more abstract style, in that kind of writing where one has been singing a melisma for so long one forgets which vowel-sound one has started with, and has to turn back a page or two to find the beginning of the word. Byrd, like Lassus, was heading for the baroque way of setting words, however obliquely.

Acquiring this sense of architecture takes time, more time for Tallis and Parsons than for Byrd (and more time for composers of an earlier generation, like Josquin and Isaac, than for High Renaissance men like Lassus and de Rore). This begs some questions about the rehearsal process. Certainly the conductor should try to come to the first rehearsal of a new large wedge of abstract polyphony knowing how he wants to shape it. The problem is that no amount of poring over the score in silence — or playing it through on the piano — is going to tell him exactly what he needs to know. Not only is it hard to hear six or more polyphonic lines in one ‘s head at once, but also, separate from the mood suggested by the texts, most of this music really does have a logic of its own. Trying to explain this logic in spoken words, and thence to dynamic schemes written into copies, is unlikely to produce anything very organic, and it may take a long time. it is obviously better to experience the music as music several times, before one can begin to claim that one knows it. In fact it is one of the great strengths of polyphony that much of it is sufficiently complex to bear almost endless repetitions, and for the performers still to find new perspectives in it. Ideally, then, one would sing the music through repeatedly in rehearsal before presenting it to the public, yet both in the amateur and the professional context this is hardly ever done with profit. A good performance of polyphony will depend on mastering an endless succession of tiny details, the kind that don’t want to be drilled into people’s heads in rehearsal and exaggerated in performance, even if they can all be remembered. The only way is to feel them instinctively in the singing, which is as much a test of musicianship as of vocal technique. Rehearsals in this way of looking at polyphony rapidly become the occasion for doing no more than establishing that the notes are right (as much in the copies as in the singing), which may mean only going through a new piece once before its first public airing.

In this matter of overall architecture, mass movements, and especially parody mass movements, present a case a little apart. In many polyphonic settings of the Ordinary quite a lot of material does in fact come round repeatedly, though not exactly in the later sense of recapitulation. The problem for the composer of a Gloria or Creed was that he had to set a long text. One way round having to invent new points of imitation for every sub-clause of these texts was to rework old ones taken from the model; and one of the pleasures of conducting a parody mass, for example, is to see how an imaginative composer re-presents this old material to new words. Through this reworking of common material all the five movements of a setting become linked, obliging the conductor to think carefully about relative speeds in the interests of variety. Of course originally the movements were broken up between the sections of the spoken service, which certainly took the pressure off dreaming up subtle speed changes; but there is real interest in the modern concert way of singing a mass setting, movement after movement straight through, as well. I would argue that in the hands of a master, parody technique rather benefits from our kind of presentation — a five-movement ‘symphony’. But perhaps it is more accurate to liken this to a gigantic set of variations on a theme than to a symphony, even though each movement has a character. The Agnus, for example, ensures that the sequence usually ends with a slow movement.

In this context it is of course a great help if the conductor has a good sense of the overall architecture, this time over five movements. If he has he may, for example, think twice about taking the first section of the Creed at the same speed that the Gloria has just ended with, which in turn may reflect the tempo at the opening of the Gloria. In the more elaborate settings, making the Creed a kind of mirror image of the Gloria means that many minutes may go by in the performance with substantial chunks of music all at the same tempo (in the case of Morales’ Missa Si Bona Suscepimus, for example, this amounts to 25 minutes), which may be throwing away an opportunity. I do not necessarily mean by this anything radical: very slight changes can produce the same sense of a new context as bigger ones. Subtly varying tempi will give new perspectives to old material, which fits in well with the underlying principle of a parody. The question of whether to change speeds in the middle of a movement (for example speeding up at ‘pleni sunt caeli’ or slowing down at ‘Et incarnatus est’) in musical terms is part of the same perspective-building. To put it another way: the borrowed material may be enhanced as much by being laid out for inspection at different speeds as by having new counterpoints thrown round it (and to have both is even better). In this way the conductor can take a front seat in the creative processes, especially if the composer has not been particularly imaginative in his parodying (one thinks of Lassus).

Vocal timbres and numbers of singers to a part

I have mentioned my sonic ideal but not the kind of voice which will produce it. As I hear it polyphony needs bright, strong, agile, straight but not white voices which have a naturally good legato over a wide range. Virginia Woolf ‘s summing-up of Proust’s prose style (quoted on p.14) expresses my ambitions perfectly. Other directors who specialise in renaissance music, especially non-English ones like Paul van Nevel, seem to think it needs quite small voices, closer to the timbre of the recorder than the natural trumpet. This may reflect the kind of singer available locally who, the moment they receive any vocal training and learn to project their voices, do so with vibrato, obliging Paul and his colleagues to use relatively untrained voices; or it may come from a belief that the clarity of the part-writing is better served by voices with few overtones. I have some sympathy with this view, and have admired van Nevel’s very different versions of works we have also sung (especially the big pieces like Brumel’s 12-part Mass; Tallis’s Spem; the Josquin 24-part canon); but the overall effect is less thrilling, less brilliant, too fussy. I want a core of steel to the sound, and in trying to create it I believe we have encouraged the development of a new kind of professional singing voice, the kind that projects to the back of the Sydney Opera House without employing distorting vibrato (remembering there will always be some vibrato).

Van Nevel’s recordings show that he would support me in saying that the audibility of all the parts equally is a prime consideration in singing polyphony. Not to work towards this is to show scant respect for the very nature of the writing. The necessary clarity can only be achieved by good tuning and good blend. Bad tuning will make the texture muddy as the lines blur, and bad blend will cause individual voices to stand out of the texture, making those lines consistently more audible than others. It follows that I want a singer who can sing with colour in their tone without generating mud; who can listen while singing loudly; and who has the flexibility to sing with sensitivity over the wide ranges which renaissance composers preferred, since for most of the period the modern SATB choral ranges only very vaguely applied. I choose to employ two singers to a part rather than one because I specifically want a choral, blended sound, not the sound which comes from having one voice to a part with all the breaks in the legato which that implies. And I suppose ultimately I would do what the leading renaissance choral foundations did, which was employ the most musically intelligent people available, not just those with fine voices.

It has mattered that in all the voice-parts the chosen singers should come to the group with the same types of voice, but it has mattered more that the sopranos did. And, once there, in order to maintain the ideal, they have had to follow stricter guide-lines than the singers on the lower parts, not just in singing two to a part even in eight-part music where the other lines are being sung solo, but in working more precisely in the business of ‘staggering the breathing’. There have been times when an audience has not noticed the presence of an unsuitable alto, tenor or bass (though repeated listening would soon give the fact away); but it is impossible to mask an unsuitable soprano timbre, from the very first phrase. Any lingering idea, incidentally, that these sopranos sound like boys is just proof that the person who thinks it has not listened closely to either party. Certainly these sopranos sound MORE like boys than the traditional operatic soprano, but that is a benchmark so wide of what is being discussed here that it is effectively irrelevant.

So how many voices to a part is ideal? Right from the start I decided that two was the optimum. With two you have a properly choral sound, in which the participants can be closely in touch with each other while maintaining an uninterrupted legato by virtue of staggering the breathing. They are likely to blend better than one to a part, where the danger of individual voices obtruding is greater. One to a part has the obvious merit of easy interaction between the singers, where the chances of subtle phrasing and rubato are increased, but this only works really well in music which has short or easily sub-dividable lines. The much longer lines and sheer sonic weight of mid-period polyphony in my opinion requires the delivery of a chamber ensemble.

Three or more voices to a part can provide this weightier sound, but as the numbers increase so the law of diminishing returns may apply. With three singers to a part there is the problem that two of them are not next to each other, which will reduce the fluency of the things they all need to do together as if they were one: breathing, tuning, blend. With four this lack of fluency will be all the greater, and so on as the numbers increase. In my experience the moment the numbers go above three I am dealing with a different kind of sound, and usually with a different kind of singer — the sound more generalised, the responsibility of each participant reduced to the point where I as the conductor have to decide everything since no one in the choir can hear what everyone else is doing. With two everyone can join in because they can hear enough to do so, and yet the sound is choral. As I argue above, it is better if everybody present contributes to the interpretation on the spur of the moment in the concert: singers and conductor. Increasing the numbers steadily reduces the chance of that happening.

I accept that three or four voices to a part could blend well, given the right mentality from all the singers, and a not too reverberant building.

Here we bump into another sacred cow, left stranded from a previous way of approaching this music. Vast churches with generous acoustics have long been thought by some to be the ideal places for singing: the vision of the angelic choir from afar, their sound haloed by the reverberation possible down a Gothic nave has proved very seductive and durable. The problem is that even a little reverberation can actually destroy polyphony, in exactly the same way that excessive vibrato in the voices can destroy it, because of its nature polyphony relies on a constant supply of chamber-music-like details for its interest, which in very reverberant acoustics will blur into a succession of not very interesting chords. This blur also makes it much harder for the singers to hear each other, and so agree on an interpretation, further reducing the subtlety of the experience for the listener. Very dry places can be hell too of course, but some of the drier ones at least create the circumstances in which a sensitive and interesting performance can take place, where the singers are fully in control of what they are doing and the audience can hear everything. My favourite venues for sacred polyphony are those modern symphony halls where the acoustician has produced a clear and rounded basic sound, often controllable these days by opening and shutting doors to special acoustical chambers in the gods.

It stands to reason that polyphony should be sung in a style derived from the music which preceded the renaissance period, rather than from the music which succeded it. But however much it may stand to reason, in practice it is impossible to undo the training we have all had in later repertoires; which is just another way of saying that we live in a different era from the renaissance and are entitled to bring music of the past alive to modern ears. Over the years The Tallis Scholars have felt their way towards a balance between singing with voices trained in a modern way and singing in a style which we think suits the music. This is a compromise, but at least it has come from specialising in this one repertoire, and thinking only about how best to put sound to it. The ideal in one way would be only ever to have sung plainchant before approaching polyphony, to know only the kind of legato which that music requires, to feel the way chant melodies flow and build and fall away, never to have been in hock to a bar-line. But the untrained voices of monks, as can be heard on the historical recordings of the monks of Solesmes, only have a limited impact, which would not have enough purchase in a modern symphony hall to hold a large audience. Our compromise was inevitable and, judged by the strictest standards of what the music demands, its success has been partial. I have never heard a choir trained only in plainchant singing polyphony so that a big hall can be filled by their sound, and I never will.

But I have heard countless choirs singing polyphony in mixed programmes with later music and have noted how uncomfortable the early repertoire can sound, hijacked by four-bar phrasing, sudden dynamic shifts, little sense of where those long, melismatic phrases are going. (The nearest one is likely to get to this ideal is with choirboys who spend much of their singing lives concentrating on chant in services. of course they are still modern people, influenced by listening to later music, but I was struck by hearing the boys of Westminster Cathedral sing some harmonically-based Romantic music recently. It sounded stylistically challenged because they had been taught to sing the words legato, as suits the performance of chant, running the syllables together in a smooth continuum quite unsuitable for the boxed-up phrases in question. But for decades now they have been famous for their stylish performances of polyphony, that style greatly aided by their daily experience of chant-singing. It was a pleasure as well as an education to sing some of the night Offices alongside the men of this great choir in September 2012, as part of a choral festival hosted by Martin Randall).

I never audition singers because I doubt that I shall be able to tell from their prepared pieces how well they can sing polyphony. Presumably I would learn something about the type of voice they have and how quick they are at sight-reading, but I shall not learn how well they listen to their neighbours, how instinctively they are prepared to blend with them and what feeling they have for melodic lines which only exist in the context of other such lines. We are fortunate in having a wide choice of candidates in London, and these days I tend to leave the final decision of who will join us to the singer whom the newcomer has to stand next to. That way there should be a meeting of minds, at least, before we start. And just as I may never have heard a singer before his or her first rehearsal with us, I am careful to judge very little on that or any rehearsal, but only by what I hear in concert, and preferably across many concerts. The only fair way to judge a singer who has an aptitude for polyphony is to judge them across an average of what they do, both because the demands of the repertoire are varied and everyone is entitled to an off-day. I have thrilled to the debut of people who can realise the most perfect high Palestrina part in the relaxed circumstances of a rehearsal, only to wonder what I was so excited about when listening to them sing it in bad acoustics in a concert; or when fate dealt them a part which lay consistently just too low for them (in bad acoustics in a concert). The average is crucial, not to mention the time it takes for a newcomer to get used to the minutiae of our style — the meticulously metrical placing of the shorter notes — newcomers standardly rush quavers and semiquavers for a good few months; acquiring that desired legato phrasing throughout a whole programme; not half-expecting the music to slow down (and go flat) at the soft passages or speed up at the loud ones.

Performing pitch

One of the decisions the conductor of polyphony has to make in advance is what pitch to sing it at. By and large we have adopted a theory of transposition which was given wide publicity through the performances David Wulstan and the Clerkes of Oxenford in the 1970s, but which had been in use from the first decades of the 20th century. In essence this is to transpose much of the English repertoire up a minor third from written pitch on the grounds that a written note in the renaissance period represented a sound nearly a minor third higher than what that written note means to us. The theory is at its most contentious when applied to English music because of the specialist high treble part which results from it, but in fact many other repertoires have been habitually transposed up, also for many years. Whatever one thinks of the evidence, the results can be very distinctive. I mention this here because the decision whether to transpose or not has serious repercussions for the balance and the clarity of the ensemble. We have been criticised more consistently and with greater reason for our high-pitch interpretations of English music than for anything else. It is indeed likely that if the top part (called ‘treble’) goes very high the lower parts, especially if they include one or more low Tudor countertenor lines, are going to be obliterated. There are two alternatives: be inconsistent – because it has long been standard practice to sing the non-treble repertoire up a minor third or more – and sing this particular repertoire at untransposed pitch; or shape up to the demands.

I still choose to grapple with the rather exotic problems of the high pitch solution firstly because I miss the light-weightedness of the sound at written pitch, and secondly because I find that the imbalances caused by the voice-ranges at high pitch are simply transferred down the texture at low pitch. Of course it takes a little longer to notice them, since the highest part is not involved any more, but sooner or later one wishes the tenors would not have to sing so high so consistently, especially with the basses now rather low for many bass/baritones. The altos (now singing ‘mean’) too can sound uncomfortably high with the result that the bass part of the overall sound can disappear, while the middle of the texture is in danger of being over-stated and thick. Preferring antiphons to sound more airy than massive, I have tried to produce a treble part which is gossamer light. This is a very difficult thing to do and anyway it took many years to hone. In the early years of the group there was a constant danger of the singers, and the audience in sympathetic reaction, coming away from the bigger pieces (and they are long) with sore throats. Now, not least in Spem which has eight of these high parts, experience has suggested the way forward. It is possible to float them in such a way as to make them sound expressive rather than demanding, and to go some way towards keeping a good balance with the lower parts. Our latest recording— of Taverner’s Missa Gloria tibi Trinitas – in my opinion represents a further step on the path to a satisfactory overall balance between the parts in a truly massive treble-pitch composition.

One way to help the balance is to employ a high tenor on the countertenor parts alongside falsettists. In the same way one can also add a high baritone to the tenor part or even to the countertenor parts — Bertie Rice, a baritone, dubbed in the low notes on both countertenor parts throughout the Gloria tibi Trinitas sessions). The need for these combinations is really only an admission that renaissance voice-ranges do not conform to what we expect and what is taught in singing-lessons today, something which has to be faced up to not just in Tudor polyphony but in most Flemish polyphony too. Singers of this repertoire simply have to be prepared to adapt what they know to the circumstances, and in the case of doubling with another voice type this means taking over or yielding the line as it comes into or goes out of one’s range. At the same time all the singers on the line need to contribute to the overall interpretation, which requires a degree of sensitivity unlikely to be found in the kind of professional who comes to the job thinking ‘this is what I’ve been taught to do, this is my voice-type: I’m not prepared to sing in any other way’. One sympathises with, but does not employ such thinkers. And speaking of androgyny, it has been a source of strength in The Tallis Scholars in recent years to have employed a male and female alto alongside each other. Originally, when we were still trying to ape the cathedral set-up, it was thought that this was going too far in the direction of a purely secular sound. But it has worked really well, yielding a perfect blend and giving the flexibility of an overall range which can be very wide if the male will sing in chest voice for the lowest notes and the female will fill out the most difficult notes for a falsettist, in the middle of the range. The success of it stands as a tribute to the sensitivity of the singers in question: Caroline Trevor, Robert Harre-Jones and Patrick Craig. We have never employed a female tenor, though in theory we would.

These tessiruras beg the question what kind of performer renaissance composers did expect to use, since it is hard to believe that throats have changed that much in a few hundred years, or that diet has had quite such a transforming effect on ranges. My guess, which can never be proven, is that once again later thinking has got in the way. It is very likely that in the days before voices had to be heard over orchestras modern techniques of projection were not considered. When popular vocalists today sing to themselves (or down a microphone if in public) they make no attempt to project their voices, but sing lightly in the throat, head-voice or falsetto as the range requires. Renaissance ranges strongly suggest that this was the contemporary singers’ method, implying that we should model ourselves not on Jessye Norman but on Sting. No self-respecting singing academy would charge to teach people what they can do naturally, which would explain why there isn’t any evidence of voice tuition until instrumental participation forced the issue. I also take the point that if I am correct I am presenting just another argument which shows that the loud, steely-bright sound The Tallis Scholars make must be far from how renaissance choirs sounded.

Apart from the unfamiliar ranges which Josquin, Cornysh, Taverner and their mid-renaissance contemporaries regularly deal the modern choir, there is the less discussed problem posed by Palestrina. This forms a little area for study all by itself. Where English composers tended to double the countertenor part when writing in more than four parts, Palestrina doubled the tenors. Not only is this inconsiderate in the modern context, where tenors are the least findable of all the voice-ranges, but Palestrina compounded the problem by writing unusually high parts for these tenors, regularly peaking on high A at written pitch. And even if high A to Palestrina and his contemporaries was not what we hear as high A, because of a concatenation of adjustments made necessary by changing practices, the ‘tenors’ will still be singing a third higher at the top of their range than the ‘sopranos’ at the top of theirs, which never happened in English music, even when the top part had the ‘mean’ range and the trebles were absent. It is rare in the Flemish school as well. The regularity with which Palestrina wrote top parts which are only a sixth above the tenor parts poses some ticklish questions about which voice-types he really had in mind. Since we know little about the sound the singers of the Sistine Chapel choir made in his time — except that there were no boys or castrati on the top part, they were whole adults of all ages — it is hard for us to imagine what sound he heard. It is too simplistic to think that there were falsettists and high tenors in abundance: there aren’t today; and anyway I doubt that the falsetto voice, in the modern sense of being used throughout the range, existed as early as this as a regularly employed instrument. But Palestrina’s voice-ranges are unique, which suggests he was writing for an ensemble which had a make-up and therefore sound not only different from ours but different from anywhere else at the time.

Modern editors, wanting to sell copies to the standard SATB choir, have tended to avoid Palestrina’s five-voice pieces in favour of his four- and six-voice ones, a policy which at a stroke has considerably restricted knowledge of his work. The modern need is to find pieces with two soprano parts, first, and two of anything else second. Five-voice Palestrina with two sopranos is very rare, whereas his six-voice writing often has two sopranos with two altos or tenors. So it is that there are many recordings of Palestrina’s Missa Assumpta est Maria (SSATTB) and none except ours of his Missa Nigra Sum or Missa Sicut Lilium (both SATTB), despite their outstanding quality. There are many more masses and motets in this awkward category. What is to be done? Everything points to the unpopular solution of transposing a very great deal of Palestrina’s music down something like a fourth, and scoring it for falsettists (or possibly just high tenors) on top, and arranging the other parts between a mixture of low tenors, baritones, basses and low basses. (The problem of the modern collegiate choir having only young voices and therefore few profundi of course did not apply to the Sistine Chapel employees, whose average age was in fact quite high.) If one were to do this across the board the current view of Palestrina’s bright, luminous sound-world would have to be radically redetermined. But although the staff-lists in the 16th-century Sistine Chapel suggest this solution, we have other options. If we transpose him down a tone his standard ranges often become a modest soprano part, ordinary alto, highish tenor and highish bass or multiple thereof. This has been the normal reading of Palestrina since he was revived in the 19th century, and looks within reasonable bounds on paper. The only problem is that the tessitura of the tenor and bass parts remains high, the tenors in particular finding a whole mass at this pitch’ extremely hard work even though they may never sing above G.

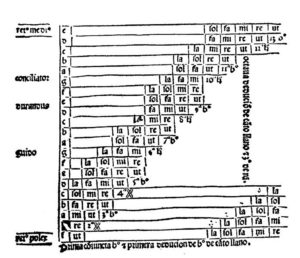

Ficta

Ficta is the one area of performance practice which leaves me cold, though I feel it should not. After all, a piece can be transformed by its ficta. The English repertoire would be quite undone if those famous clashes, most of them created by ficta, were disallowed. Gombert’s music would have been hailed years ago if he had been allowed the same ficta-rights as the English all along. But although certain basic requirements have not changed in my ground-plan for performing polyphony these 40 years — such as ignoring all the nonsense about contemporary regional pronunciations of Latin, English, French and the rest; finding just the right voices to suit my aural vision — ficta finds me fumbling and weaving, changing my mind every few years.

My craven hope is always that the editor will have been reliable in taking the necessary decisions, that those decisions are good ones, and that there is not going to be any argument about them in rehearsal. I would rather not be asked what my preference is, but if I am, my answer until about ten years ago was to cut the whole lot out (witness our recording of Brumel’s ‘Earthquake’ Mass which, as I say above, is a monument to the pre-Raphaelite approach) in the interests of consistency. Since then I have proceeded by degrees through putting in sharpened leading notes at cadences, to putting them in more widely, with every variation in between. I have finally been weaned from the faux-medieval sound which was installed in me by the editors of those daunting Complete Works / Opera Omnia editions published from the 1930s onwards, available on the shelves of all good libraries; but I have not yet fully embraced the hard-line melody-only argument which says that when the leading-note leads to the final it should standardly be sharpened no matter what the harmonic context. Nor am I always swayed by the avoiding of the tritone as a reason for adding ficta. Let them sing diminished fifths if the impact of the music benefits from it. And I am so used to pieces I first met years ago in those Complete Works — Cornysh’s Ave Maria is an example — without any ficta at all, that I find the music means almost nothing to me when ficta is added, against all my current instincts. Ironically I may be being uncharacteristically authentic when I consult only my own predilections in the matter of ficta: there is good reason for thinking that was how it was for the original scribes. The problem is that there is so much choice, and so little in the way of certain guidelines, which anyway changed as the t6th-cenrury went by.