Report by President of the Jury, Graham Lack

Some competitions are like transatlantic long-haul flights; others resemble the short hop domestic connexion. The present competition was certainly in the former category. By the final submission date, 1st October 2012, no fewer than 637 works had been received by the competition office. The jury was hence confronted with a huge task. Out of fairness to the composers, I felt as Jury President the only route through this was to ask the jurors – Libby Larsen (US), John Pamintuan (The Philippines), Olli Kortekangas (Finland) and Paul Stanhope (Australia) to look at each work in turn and suggest candidates for the second round. Allotting, say, ca. 120 pieces to each juror might have meant less work for each individual at the outset, but might well have skewed the reading process, according to personal musical and stylistic preferences. From the start we relied on each other’s views and opinions. Into the second round were customarily sent 139 compositions, ones which, in the opinion of the jury, merited further discussion. In the interests of transparency, I can tell readers that this stage took place in a cloud computing environment, although I can not of course reveal details of those virtual discussions. Thus, just 15 pieces went through to the final round, which was held as a lengthy Skype conference that initially connected the US with Finland, Australia with Germany, The Philippines with Italy (Rimini in fact, where the Competition Adjudicator, Andrea Angelini, was looking on and listening in) and, of course, everyone with everyone else. Marvellous when technology works; hideous when it does not…

From the outset consensus politics had been preached, and it was a most gratifying feeling when we realised that only three works were in the frame – our real candidates, our three prize-winners. After some discussion, which was informative, courteous and constructive throughout, the outright winner emerged: Francis (Frank) Corcoran (Ireland), for his Eight Haikus. He receives € 5,000 along with a Competition Diploma. The work will, as detailed in the rules, now be premiered by the Philippine Madrigal Singers, on 5th and 6th October as it turns out. As for the two Special Prizes, these were awarded to Itzam L. Zapata Paniagua (Mexico), whose On Desire functions, in the opinion of the jury, as an ‘Original Sonic Landscape’, and Rudi Tas (Belgium), whose Pie Jesu, again according to jury opinion, displays ‘Notable Harmonic Originality’. The former work will be given a workshop and possibly premiered by VOCES8; the latter piece will also be part of a workshop with the Kammerchor Consonare Hamburg, and may well be premiered too. We hope the two composers will manage to attend.

It was decided to make a number of Honourable Mentions. These included Ivan Bozicevic (Croatia) in the category Suitability for Youth Choir for his Yuku haru ya; Xingzimin Pan (USA) in the category Suitability for Community Choir for his Poem I; Christopher Evans (UK) in the category Suitability for School Choir for his Far on the Sands; and Gaetano Lorandi (Italy), whose Ave Verum demonstrates good Repertoire Value in addition to being a Well-Crafted Manuscript. Simply put: congratulations to all seven composers.

To come back to the point about the sheer number of entries, we wondered what had precipitated such a phenomenon. First and foremost there had been a successful advertising campaign, and the news had got out to composers around the world, to conservatoires and academies and their composition teachers and professors, and to choir directors and to singers; secondly, this was a competition with no entry fee, and no restrictions like age limit, or nationality and country of residence, the works were just to be a cappella, scored in up to eight parts (SSAATTBB) for mixed voices, and no longer than eight minutes; thirdly, there was no actual theme to the competition, composers were free to set any text in any language (with English translation where appropriate and necessary), whether sacred or secular, whether old or new, whether published or unpublished (copyright clearance of texts not in public domain was the business of entrants prior to submission); and fourthly and finally the outright prize-winner was to receive a generous amount of money (a decision for which IFCM President Michael J. Anderson must be thanked) and the work selected would be premiered by a named ensemble.

(Click on the image to download the full score)

(Click on the image to download the full score)

(Click on the image to download the full score)

The standard was high, certainly higher than was the case with the First International Competition for Choral Competition, held in 2010. It seems most composers had understood a few things: just how important range and tessitura are, that voice leading must create horizontal sense, that a work should maintain some sense of harmonic progression – or logic at least, how vital it is that music be made to match the text, and how necessary it is to write for the voice, each voice, every voice in an ensemble, and not sacrifice ‘singability’ on the altar of choral effect.

On a more, and I hope not churlish, note, it was disappointing to see how many composers were prepared to sign an affidavit of legal standing to the effect that a work had never previously been performed, where this was clearly being economical with the truth. A quick trawl of the Internet by the adjudication panel revealed much: the World Wide Web is a poor place to hide. Other works which actually had not been performed before the date of submission were found to have received premieres between that time and either before the final competition submission date or prior to the jury announcing its decision. The letter of the law may be seen to have been obeyed, but the spirit of the law – where for obvious reasons pertaining to the preservation of anonymity alone it is assumed the jury will be considering only unperformed works until such time as a decision is announced – had certainly been transgressed. In addition, the main prize included a premiere, which counts out such works.

A number of pieces along with their composers were thus disqualified. At best, and to give as many composers as possible the benefit of the doubt, some workshop renditions which had found their way onto various websites were clearly cases where the entrant did not classify these as performances proper, and did not see them as being in the public domain; at worst, there were a few cases where a work had received a world premiere, one given by a renowned ensemble in a concert hall very much part of musical life of a large city, with a press and PR campaign up front, and with several reviews in well-known newspapers and trade magazines after the fact. This can only be interpreted as an attempt to obtain money by deception. And a dim view of this was taken. Whether or not the ICB is the right forum to air these views might be debatable, but there should be no taboo subjects, and I feel strongly enough about what was a parlous state of affairs as judging began.

Let me end on a more positive note: the work that gradually drifted to the surface and which began to percolate the minds of the jurors is a fine composition. It is not an easy sing. I shall make no bones about that. But the guidelines of the competition clearly announce a chief aim which is to “promote the creation and distribution of new, innovative, and accessible choral literature.” As for the last criterion, accessibility, well, I am sure there are enough choirs and smaller ensembles in the world whose singers will solve technically what might at first sight be perceived as an intractability of the rhythmic language in Frank Corcoran’s Eight Haikus and grasp immediately the arguably recondite nature of the beautiful if fleeting melodies, based as they so plainly are on harmonical proportions. All in all it is a compositional tour de force and a great but not insurmountable musical challenge, one to which a number of groups around the world will certainly rise. And if the music proves a touch beyond that which one’s choir is capable of at the present time, directors can turn perhaps to the excellent works by Itzam Paniagua and Rudi Tas, or to the works of those worthy contenders who received an Honourable Mention in a particular choir category: Ivan Bozicevic, Xingzimin Pan and Christopher Evans. Finally, it was a pleasure to read around 30 works sent as MSS, these hand-written scores allowing the jury a different kind of insight into the musical processes at work within a particular composition. So we were glad indeed to single out one which is especially well crafted, that by Gaetano Lorandi.

We hope the International Competition for Choral Composition will go from strength to strength. The next one is the third – it is a biennial event – and is scheduled for 2014. Gosh, that is creeping up on us already.

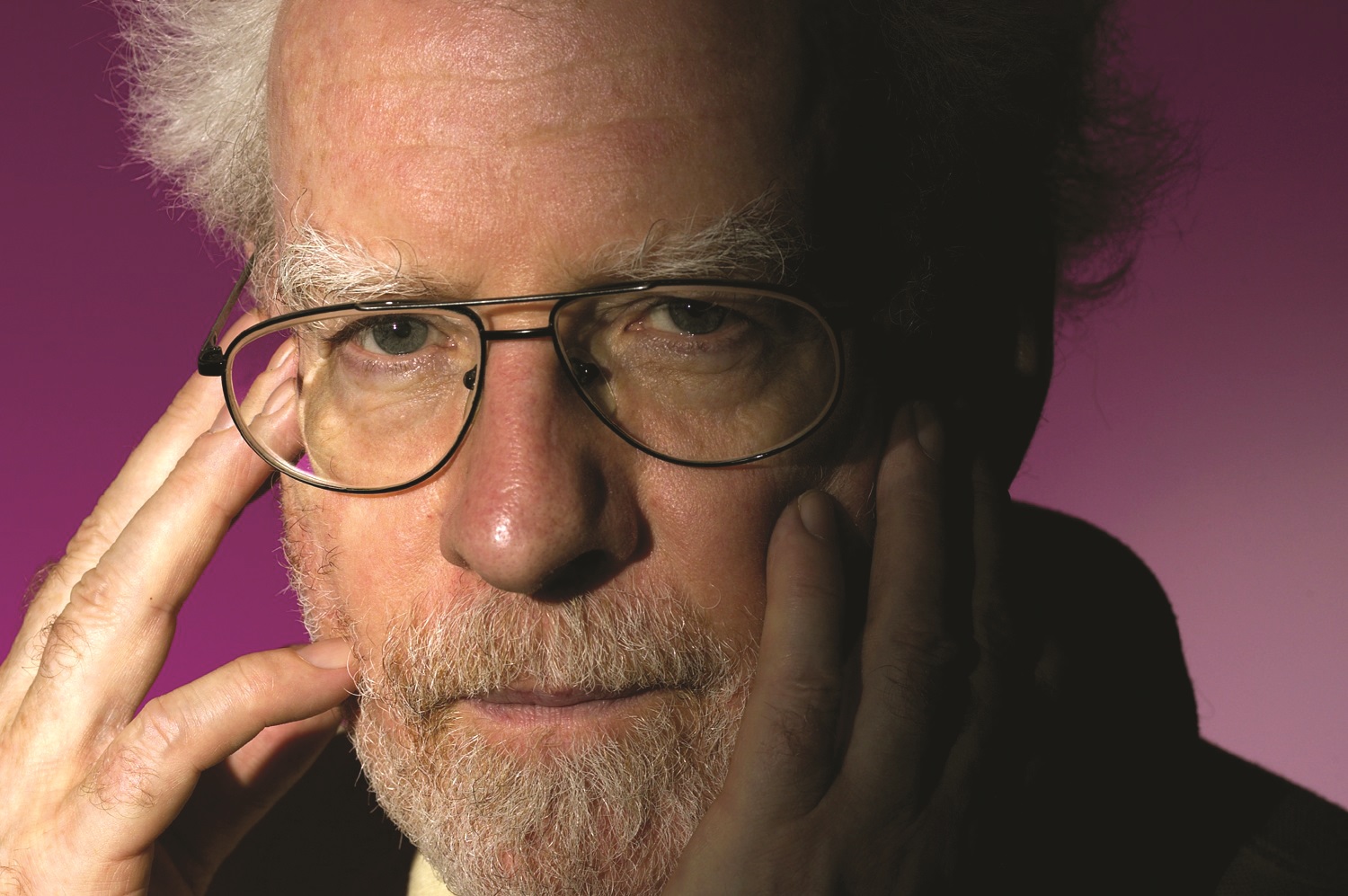

Frank Corcoran (b. 1944)

‘I came late to art music; childhood soundscapes live on. The best work with imagination/intellect must be exorcistic-laudatory- excavatory. I am a passionate believer in “Irish” dream-landscape, two languages, polyphony of history, not ideology or programme. No Irish composer has yet dealt adequately with our past. The way forward – newest forms and technique (for me especially macro-counterpoint) – is the way back to deepest human experience.’

Frank Corcoran was born in Tipperary and studied in Dublin, Maynooth, Rome and Berlin (with Boris Blacher). He was the first Irish composer to have his ‘Symphony No. 1’ (1980) premiered in Vienna.

He was a music inspector for the Department of Education in Ireland from 1971 to 1979. He was awarded a composer fellowship by the Berlin Künstlerprogramm in 1980, a guest professorship in West Berlin in 1981, and was professor of music in Stuttgart in 1982. Since 1983 he has been professor of composition and theory in the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Hamburg. During 1989-90 he was visiting professor and Fulbright Scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and he has been a guest lecturer at Princeton University, CalArts, Harvard University, Boston College, New York University and Indiana University.

His works have been performed and broadcast in Europe, Asia, USA, Canada and South America. He has been commissioned by NDR, RTÉ, the Arts Council, U.W.M., Sender Freies Berlin, W.D.R., Deutschlandfunk, North South Consonance New York, Dublin Living Music Festival, Cantus Chamber Orchestra Zagreb, Dublin Festival of Twentieth Century Music, AXA International Piano Competition, Wireworks Hamburg, Slí Nua, RTÉ lyric fm, Now U Know Washington, New Music Boston, Carroll’s Summer Music, Book of Kells U.W.M., Crash Ensemble, Hamburg Ministry of Culture, Tonhalle Düsseldorf, Stuttgart Bläserquintett, the Irish Chamber Orchestra and the National Chamber Choir of Ireland.

Awards include Studio Akustische Kunst First Prize 1996 for his ‘Joycepeak Music’ (1995), Premier Prix at the 1999 Bourges International Electro-acoustic Music Competition for his composition ‘Sweeney’s Vision’ (1997) and the 2002 Swedish EMS Prize for ‘Quasi Una Missa’ (1999). He was also awarded the 1972 Feis Ceoil Prize, the 1973 Varming Prize and the 1975 Dublin Symphony Orchestra Prize. More recently he won the Sean Ó Riada Award at the Cork International Choral Festival 2012 for his ‘Two Unholy Haikus’. CDs of his music have been released on the Black Box, Marco Polo, Col-Legno, Wergo, Composers’ Art, IMEB-Unesco, Zeitklang and Caprice labels. Frank Corcoran is a founding member of Aosdána, Ireland’s state-sponsored academy of creative artists.