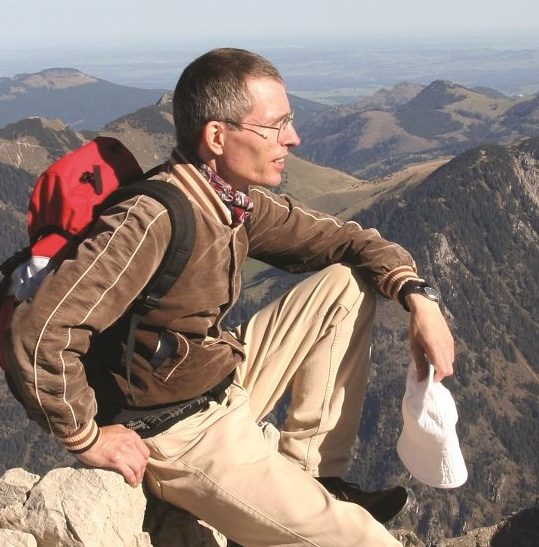

Paying a visit to Wolfram Buchenberg in the Bavarian Allgäu

Interview by Arne Reul

The music of Wolfram Buchenberg is becoming more and more established in the repertoires of numerous choirs. The choral music label Spektral will soon release a CD of a cappella music, the first to be exclusively dedicated to the composer, sung by Cantabile Regensburg under Matthias Beckert. Ensembles searching for sophisticated contemporary literature will find what they are looking for in the works of Buchenberg. Works like Ich bin das Brot des Lebens (I am the bread of life), Von 55 Engeln behütet (Protected by 55 Angels), Veni dilecte mi, and Vidi calumnias et lacrymas have been enthusiastically received by the public. And some of his charming folksong arrangements, such as Kein schöner Land (No land more beautiful) have even been sung by choirs in America and Asia.

It is no coincidence that this native of the Allgäu region has enriched choral music in particular with respect to sonority: the beauty of a mountain panorama can, in a way, be transposed to the vertical plane of a musical composition – just like Buchenberg transforms the interaction of voices into sophisticated and appealing choral sounds. Recently, Neue Chorzeit met up with the composer in Marktoberdorf, where he spends many weeks each year composing.

Arne Reul: Herr Buchenberg, many of your compositions are commissioned works for choirs. How did you get started on that?

Wolfram Buchenberg: The first choir that I composed for was the Madrigal Choir of the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Munich, in which I sang in for twelve years. I knew exactly what this choir was capable of musically, and I was able to use that knowledge to compose accordingly. I’ve continued writing at roughly that level of difficulty, i.e. for ambitious or semi-professional choirs.

AR Working directly with choirs can really give new motivation to a choir. Do the choirs or choirmasters come to you? How does it work?

WB Usually, a choir director comes to me asking for a composition for his or her choir – often for a concert. If I have the time and the project interests me, I’ll first want to know what kind of a choir I’m dealing with and how much I can demand of it. I want to get to know the choirs that I work with because after all, I have to compose something that they are capable of singing. I have managed to compose something that is challenging, without being either too easy or too hard. In most cases, I aim for the upper limit of what a choir is capable of. If I really demand a lot from a choir, then they’ll have to exert themselves, but they learn from it and afterwards they can also be a little proud.

AR Do you also attend rehearsals?

WB When I have the opportunity, I like to sit in on the rehearsals because that way I get feedback. I can also get a better idea of exactly which sections of the piece are giving the singers trouble. Getting feedback is helpful for when I compose other pieces in the future.

AR Many of your compositions are incredibly gratifying pieces for the choirs. Your music is very singable, and the singers can really wallow in the melodic element…

WB I think that there are always links in my music with older choral literature. I want to compose music that is always melodic and singable, I will never demand anything that is unpleasant and potentially even vocally damaging. While I am composing, I always try out everything myself. If I wouldn’t inflict something on myself as a singer, then I won’t inflict it on any choir either. But there also are techniques that you won’t find in traditional choral music. The sounds alone are different now from what they were 100 years ago. Also, there’s voice-leading with diverging sounds, where all the singers in the choir sing individually and independently from their neighbours.

AR And then there are very demanding rhythmic passages as well…

As far as complexity is concerned, I try to strike a balance. If the harmony is difficult, then I try to make the voice-leading easier within that harmony, so that it is still do-able for non-professionals. If I made everything (rhythm, harmony, melody) extremely complex all at the same time, then I would really need to get professional choirs who never do anything else but sing such music. What I strive for, in a way, is to strike a good balance between the difficulty of the music and the impact that it has on the listener. By all means, a piece may be difficult, but that difficulty should also add something to the music. What’s the point of music that is just difficult, but that doesn’t sound good?

AR You also compose for children’s choirs. There are smashing pieces like ‘7 Zaubersprüche für Mädchenchor’ (Seven Magic Spells for girls’ choir), ‘Silere et audire’, and the syllabic ‘Gulla, mille gullala bena’.

WB I have to admit I don’t really like composing for children’s choirs because it is very difficult. It’s easiest to compose for professional choirs, since you can basically expect them to be able to handle just about anything. Then, putting it colloquially, I can just write as it comes. But the less experienced the choir, the more difficult it is. And the harder it is for me to remain true to myself, because I usually do have a specific sonority in mind. Composing music for a children’s choir that is both exciting and do-able really is like trying to square the circle.

AR What’s remarkable is that you often incorporate elements of movement for the children’s choir – and at the same time, there are pieces that, rhythmically, are very tricky.

WB I think that kids generally sit around too much and so it’s important to get them to move around. Children need to unwind physically, and I think that it’s important to give them the opportunity to do so. Some young people can hardly manage to stand on one leg, and others have trouble coordinating their own body movements! However, I think that we shouldn’t underestimate kids. ‘Silere et audire’ is a piece with Latin lyrics written by Anselm of Canterbury. If you open up this world to the kids, you can also expect them to be able to handle more difficult texts. At least they’ll be able to sense the atmosphere. I think that such meditative phases are just as important for kids as is the opportunity to express themselves rhythmically, like with ‘Gulla, mille gullala bena’, which is very strongly based on the rhythms of an [invented] language.

AR You mentioned Anselm of Canterbury. About half of your choral works are sacred music. What is your approach when it comes to sacred music?

WB There are great sacred texts out there that really speak to me, and so I find it completely natural to put them to music. Many of the texts that I treasure are not very well known, for instance those of Meister Eckhart or, as I say, Anselm of Canterbury. Through my music, they reach a wider audience. I usually find that sort of thing more interesting than setting yet another Magnificat to music.

AR You also arrange folksongs for choirs. Out of all the work you do, where do these arrangements fit in your output?

WB I don’t focus on it that much any more. I do enjoy it because I like folklore and folksongs, but in the end it’s more a craftsman’s job tackled with significantly less doubt than when I compose my own works. Some of these arrangements were actually created for performance by schools or youth choirs, so you could say it’s my practical service to humanity. (laughs) But I’m really delighted that ‘Kein schöner Land’ is being sung so much. There are probably even people out there who only know me because of that piece. Sometimes I think of how Carl Orff must have felt, knowing that most people were only familiar with his ‘Carmina burana’. How awful! To leave behind such a vast body of work, and only one of them really sticks. I hope that that will not be the case for me with ‘Kein schöner Land’. It doesn’t matter to me whether it’s sung by a Japanese, English, or Korean choir, the only thing that I really care about is that they sing it well. Even though, naturally, in terms of language it wouldn’t be quite the same.

AR To all intents and purposes, folksong arrangements also offer choirs the opportunity to move indirectly towards contemporary choral music via a familiar piece.

WB Since the singers already at least know the tune, the initial anxiety is diminished. But, they always say that people are afraid of contemporary music. In my experience, it’s the complete opposite! Take a look at the programmes for the Marktoberdorf Chamber Choir Competition – many people expect to hear contemporary choral music, and they’re disappointed if they don’t. If the music is well performed, you can make a much greater impact with contemporary music than with older, more familiar pieces. I’m very certain that the quality of a choir improves when it tackles contemporary music.

AR Your latest choral piece, ‘Tombeau de Josquin Desprez’, is for 16 voices.

WB That is a piece that I initially began on my own initiative. I stumbled upon the text and wanted to make a 16-part piece out of it. But if you have no performance date scheduled, then such a work can end up just sitting there for ten years. So when Martin Steidler from the Heinrich Schütz Ensemble Vornbach came to me asking for a composition, I said that I would agree to do it as long as it could be that 16-part choral piece that I wanted to finish anyway. Premiering the piece with the Via-Nova-Chor München as well was an ideal collaboration.

AR How do you deal with sound when you compose for 16 parts?

WB First of all, when you compose for a 16-part choir, you need to write in a lot more rests! (laughs again) You can’t just write out 16 continuous parts. I prefer picking out certain moments during the piece where everyone comes in and sings together at the same time, as a means of building up the intensity. Also, you can then distribute the musical events more evenly on several staves more easily. Thus, having more parts can actually make a piece easier for a choir, because one part won’t need to struggle with a difficult leap – that’ll go to another part..

AR This piece has fascinating soundscapes, and at the same time the music is very moving.

WB I sure hope so! The 100 singers of those two choirs were really very impressive. When you have such a large group of singers and you come to a point in a piece where everyone, all 16 parts, are singing at once, and the other way round, sounds gradually disentangle themselves, it produces a sound with incredible force. If that were now sung by a notably smaller choir, they have to be really good in order to achieve that fullness of sound.

AR Is this also where your fascination for composing for voices comes from?

WB My fascination for composing for voices lies in the voice in itself. Nothing else speaks to us like the voice, with all of its expressive possibilities. And the voice has an advantage over the instrument. Right now we are talking with one another – it goes beyond the voice. Many things are being revealed unconsciously, for example states of stress. I rarely consciously decide how I talk and at what pitch, but I’m constantly influencing others by the way I talk, and vice versa. I even believe that just listening to the voice can have healing effects. It feels good to listen to some people, no matter what they’re saying – it’s just the way they talk. It often has a quite therapeutic quality.

First published in May 2012 in NEUE CHORZEIT

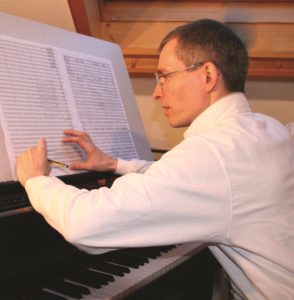

Born in 1962 in Oberallgäu, Wolfram Buchenberg is one of Germany’s most distinguished choral music composers. Well over half of his works are composed for voice. Buchenberg gained his first major musical experiences in the choral and instrumental ensembles of Marktoberdorf Gymnasium. Afterwards, he trained as a teacher for music in secondary schools, music and and also studied composition at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Munich, where he now teaches. He celebrated his first real success as a composer with the Hochschule’s renowned Madrigal Choir. In 1993 the choir won First Prize in the ‘Contemporary Choral Music’ category at the international choral competition, Let the Peoples Sing, organized by the BBC in London, with pieces that Buchenberg had composed especially for the choir, Beschwörung (Spell) and Störung (Disturbance). Since then, many choirs have taken an interest in the composer and commissioned works from him. Through close work with the ensembles, he composes expressive pieces that prove to be highly successful in performances by ambitious amateur choirs. Buchenberg’s music is both modern and sophisticated, without ever drifting into the theoretical realm, and often produces strong emotional and physical sensations. E-mail: wolfram.buchenberg@gmx.de

Born in 1962 in Oberallgäu, Wolfram Buchenberg is one of Germany’s most distinguished choral music composers. Well over half of his works are composed for voice. Buchenberg gained his first major musical experiences in the choral and instrumental ensembles of Marktoberdorf Gymnasium. Afterwards, he trained as a teacher for music in secondary schools, music and and also studied composition at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Munich, where he now teaches. He celebrated his first real success as a composer with the Hochschule’s renowned Madrigal Choir. In 1993 the choir won First Prize in the ‘Contemporary Choral Music’ category at the international choral competition, Let the Peoples Sing, organized by the BBC in London, with pieces that Buchenberg had composed especially for the choir, Beschwörung (Spell) and Störung (Disturbance). Since then, many choirs have taken an interest in the composer and commissioned works from him. Through close work with the ensembles, he composes expressive pieces that prove to be highly successful in performances by ambitious amateur choirs. Buchenberg’s music is both modern and sophisticated, without ever drifting into the theoretical realm, and often produces strong emotional and physical sensations. E-mail: wolfram.buchenberg@gmx.de

(Click on the images to download the full score)

Translated from the German by Holden Ferry, USA

Revised by Gillian Forlivesi Heywood, Italy and Irene Auerbach, Germany

Edited by Graham Lack