By Carmen Moreno, Professor of Singing and Conductor

Translated from the Spanish by Mary Coffield, UK

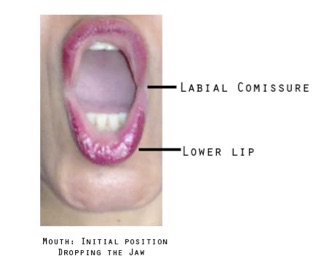

Vocalization is nothing more than a series of exercises over a variety of intervals which we carry out to gain an understanding of the strategic movements of: the drop of the lower jawbone, the lips, the corners of the mouth, the placement of sound and breath. Together these comprise the vocal technique that we apply when singing the intervals we encounter in musical compositions. The position of the mouth seconds before beginning the exercise is very important:

Corner of the mouth

Why must we vocalize?

So that the muscles have the energy and acquire the ideal muscular tone for singing. Muscles need energy to move. At the biochemical level this energy comes from the ATP (adenosine triphosphate) that is formed by the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats. The muscular metabolism required to obtain energy from ATP is activated by vocalization exercises. ATP goes through a process of hydrolysis using an enzyme to disconnect and reconnect the actin along the muscle fibre which causes the muscle to contract. During this hydrolysis of ATP heat is released (thermal energy); this released thermal energy is transferred to the musculature of the neck, face, larynx and pharynx. This facilitates an increase in the speed movements necessary for singing. In this way the tone and mechanical efficiency of the muscles used for singing are acquired and explains why lovers of singing use the term ‘warming up’ when referring to vocal exercises or vocalization. The muscles acquire the tone that is needed to sing any interval.

The choir’s Conductor ought to have previously selected a series of exercises, beginning the vocalization with an exercise over short intervals (intervals of a 2nd for example), going up in semitones to a prudent tonal height for each of the voice parts (sopranos, altos, etc.) and then descending to the initial chord of the exercise for each voice. Moreover, he or she ought to explain the purpose of the exercise, demonstrate how it is done and correct, either in general terms or specifically, any errors observed as the exercise develops.

Fig.2 Vocalization exercises: intervals of 2nd

The selection of the tonal height of the initial chord of the exercise is a decision which the Conductor should take according to the voices.

Vocalization should continue with an exercise covering intervals of a third. In this way the muscles involved are prepared progressively. It is not advisable to begin vocalization with exercises over large intervals. The effort involved in producing a sound of high intensity, without having prepared the muscles of the pharynx and larynx, can cause micro-ruptures in the muscle fibres and, if this happens repeatedly, it can lead to much more serious damage. Vocalization will continue with exercises of intervals of a 4th, 5th etc. until reaching leaps of octaves and arpeggios.

Vocalization ought to last for at least 30 minutes and can be repeated at a later stage if the Conductor considers this necessary to help the understanding of a particular interval in a piece of music.

Carrying out these vocalization exercises makes it easier to solve the problems that can arise from particular intervals in the piece of music being studied. With this in mind, the Conductor will have already studied the vocal score and will have analysed the intervals that are likely to present difficulties for the choir. It is perfectly acceptable for the Conductor to begin the study of the music with whatever bar he or she wants, but a vocalization exercise should have been prepared to help resolve any possible problem arising from singing the phrase containing the interval or intervals likely to cause difficulties.

A simple example: if the Director notices or predicts a difficulty in bar 7 of the work: Non nobis

Then he or she ought to devise a vocalization exercise with octave leaps:

The vocalization exercise ought, as far as possible, to go beyond the height of the same interval in the musical score.

During vocalization the movements of the muscles of the face, neck and larynx are synchronised and, just like the hands of a pianist, these muscles ‘remember’ how a particular interval is produced. In this way singing can be defined as: applying the habits acquired by vocalizing. Interpretation of the music is a different issue that involves adding colour through style etc., but the basic technique will always be the same. This is similar to the work of an architect. He can design a building however he likes, but whatever the construction, the bases and columns have to take account of the depth of the soil or the building will collapse.

Two interesting pieces of advice:

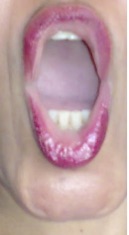

- If the melodic phrase begins with a vowel or a consonant such as K or C, on a high note, then the position of the mouth has to be as follows:

The first sounds of the phrase will be well-placed, the phrase will stay in tune and the correct placing will be maintained.

- If the melodic phrase begins with a consonant such as N, M, P, G etc. on a high note, then the initial position of the mouth has to be as follows:

Once the consonant has been produced in that position, let the jaw fall immediately to produce the vowel as in the previous image. If the consonant is well-placed, the phrase will not fall and tuning will be maintained.

In both cases the jaw bone protrudes.

Conductors ought to give due importance to vocalization. A well-delivered vocalization exercise will save time in rehearsals, provide an efficient learning method, make the choir feel secure and give the best possible results in concerts. Moreover, this approach provides a new way of working that will enhance both the group’s musical development and the conductor’s own professionalism.